ABSTRACTS Eteete Michael Adam, Babcock University, Nigeria

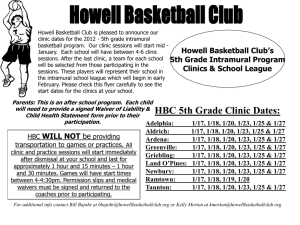

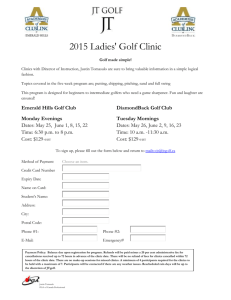

advertisement