Kuboyama2012.doc - The University of Edinburgh

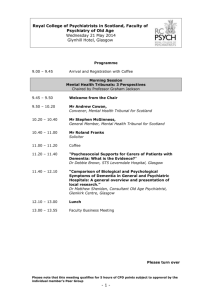

advertisement