Sara McCurry -- Most Common Errors Reference

advertisement

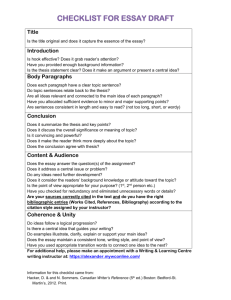

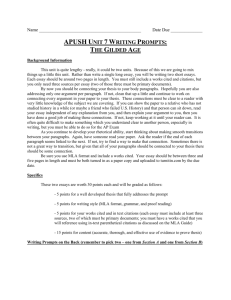

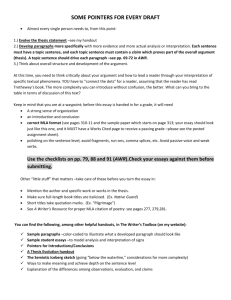

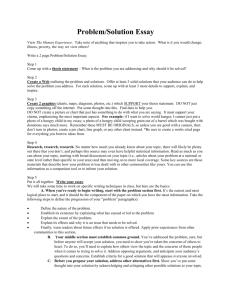

Sara McCurry, English “Most Common Errors” Reference Sheet: a strategy for saving grading time by reducing repetitive commentary on major assignments Rationale: Regardless of our academic discipline, we instructors find ourselves trying to accommodate the needs of an increasing number of students while still trying to maintain high standards of individual student feedback. The result can be frustration for students who may not feel that they are receiving enough individual guidance and burnout for instructors overwhelmed by trying to provide that essential feedback, but giving up most weeknights and weekends to do so. My challenge as an English instructor and mother of a new baby was to find a way to reduce the redundancy of some of my general commentary on student papers (for example, in a stack of 100 essays, I might write the same comment, “Your thesis statement is too general,” on approximately 40 papers). I devised a reference sheet that allowed me to streamline my commentary on general, often-seen problems in student work so that I could focus more individualized attention on other aspects of their writing. Materials: Rather than an in-class strategy, this is a grading/feedback strategy. All you need is the “Essay Comments Reference Sheet.” Description: I provide all students with a copy of the “English 1A Essay Comments Reference Sheet” during the first week of class. I explain to them that I often found myself writing the same comment on paper after paper as I graded a stack of essays, such as “too general introduction, try…” or “Where’s your thesis?” Realizing that I could both eliminate redundancy and give them more defined feedback about these very common problems, I created this sheet. On the sheet, I tell them, I give them the “best possible feedback I can give about this common problem, rather than a quick scribbled note” (students like it better when they understand that this is the purpose of the reference sheet). As I read a student’s essay, I write the shorthand version of the problem or error that I see in the margin. They look up the error on the reference sheet. Thus, I can give the best possible response to each student, offer them other resources to help fix the problem, and focus the majority of my in-depth comments on students’ unique abilities or issues. Processing/Debriefing: This method is only helpful if students actually use the reference sheet. It’s important to emphasize its usefulness; I even go through a few of the descriptions so they can see how helpful it might be. ENGLISH 1A, 1B, and 1C ESSAY COMMENTS REFERENCE SHEET TITLE 1 TITLE 2 TITLE 3 INTRODUCTION 1 INTRODUCTION 2 THESIS 1 THESIS 2 THESIS 3 DEVELOPMENT 1 Too General Title. Your title should give the reader a very specific sense of what your essay is about; don’t just call your essay “Essay #1” or “Marriage.” Your title is the first impression you convey; spend some time giving your essay a unique, interesting, descriptive title that gives a clear idea of what you will discuss. Title Format. Your title should only be centered. Don’t put the whole title in capital letters. Don’t put the title in quotation marks. Don’t bold or underline the title. Don’t make the title in a larger font than the rest of your essay. Don’t put an “extra” double space (4 spaces) between the title and text of your essay. Title Capitalization. Always capitalize the first word of the title, and all other words except the articles “a,” “an,” and “the” and short prepositions or conjunctions like “of,” “in,” “and,” “or,” etc. Introduction Too Short. Your introduction should be more than just one or two sentences and your thesis statement. Use an interesting introductory tactic to “hook” your readers and engage them in your topic before you present the specific thesis of your paper. To engage your readers’ interest right away, you can quote and comment on an interesting fact or statistic related to your topic, ask your audience an interesting question about your topic, tell a true story (your own or from a source) closely related to your topic, present a vivid image/scenario related to your topic, etc. Introduction Too General. Often, it takes a while to get in “the zone” when you begin to write, and this means that your first few sentences can be a little dull and general in the first draft, along the lines of “Global warming is a very interesting subject. It is very bad for our planet.” Focus your introduction and use it to “hook” your readers interest by using one of the introductory tactics described in Introduction 1. Too General Thesis. A thesis that is too broad (A) may not accurately reflect what’s really in your paper or (B) may indicate that you need to narrow down the scope of your paper. See Hacker C1-c (pg. 10) and C2-a (pg. 14) Awkward/Unclear Thesis. Your thesis idea is difficult to immediately grasp because of the way it is phrased. Read your thesis aloud—can you rephrase it so that your meaning is clearer? No Assertion in Thesis. Your thesis should not be just a statement of fact (like “Some children in CA experience child neglect”); a thesis needs to make an assertion that is arguable, that readers will have differing opinions about (like “California should have stricter laws governing child neglect.”) See Hacker C1-c (pg. 10) and C2-a (pg. 14) No/Poor Topic Sentence(s). Generally, each body paragraph in your paper needs a topic sentence that explains the main point of the paragraph. For argumentative papers, think of topic sentences as “mini thesis statements”; they need to be focused and specific, and usually they make DEVELOPMENT 2 DEVELOPMENT 3 DEVELOPMENT 4 DEVELOPMENT 5 STYLE 1 STYLE 2 STYLE 3 CONCLUSION 1 assertions that the rest of the paragraph backs up with evidence and explanation. See Hacker C4-a (pg. 24) No Evidence. You need to back up any point you are making in a paragraph with evidence. Some of the most common types of evidence include detailed examples (not just a quick sentence/reference in passing), quotations, statistics, analogies, historical precedent, etc. See Hacker C4-c (pg. 26) and A2-3 (pg. 70) Weak Evidence. Evidence can be weak for a variety of reasons. Here are some of the most common: (A) evidence does not clearly support the point you’re trying to make. (B) evidence is too general (make sure examples are detailed and specific). (C) source of evidence is strongly biased. No Explanation. In body paragraphs, you always need to explain how the evidence you’ve presented supports the point you’re trying to make. You can’t just give a statistic or cite a quotation and expect your reader to “fill in the blanks”; you have to explain how your evidence supports your point. Weak Explanation. (A) Often, an explanation may be weak because you are moving too fast; remember to spend plenty of time developing your explanation of how the evidence you have presented proves the point you’re trying to make. (B) Is your explanation reasonable and logical? Identify the weak reasoning and strengthen the logic in your explanation. (C) Does your explanation make generalizations or assumptions about the readers’ knowledge and/or beliefs? Identify the generalizations or assumptions you are making and decide how to better reach your full audience. See Hacker A3-a,b, and c (pg. 77) Oversimplified Style. Remember; you need to stretch your abilities as a college writer. True, you should sound like yourself and only use vocabulary that you know, but you also need to sound like an educated college student! Watch out for relying on adjectives like “big,” “neat,” “important,” etc. and adverbs like “really” and “very” to make your points. Too Informal Style. Yes, your personality should come through in your essay (even if the paper is an argument, it should still contain a sense of the writer’s “voice”). However, keep in mind that college essays are generally semi-formal to formal in tone, so avoid slang or clichéd expressions (“She got fired big time!”) or text/e-mail shorthand (“UR2 funny!”) in a college paper. Too Formal or Ornate Style. Sometimes, students err on the side of being much too formal in college papers, and the results can be peculiar instead of impressive. In general, you should write how you would normally speak—if it wouldn’t come out of your mouth (even on a good day), then don’t put it on paper. Good writing is both clear and concise— these qualities do not make it simplistic. Some of the problems that arise from too formal or ornate style are: (A) confusing/awkward sentence structure. (B) incorrect or unclear word usage. (C) a writing voice that seems antiquated, peculiar, or simply false to the reader. Too General Conclusion. Often, writers feel “out of gas” by the end of the paper and write a conclusion along the lines of “Global warming is bad for the environment. We all need to do something about it.” As in your CONCLUSION 2 MLA 1 MLA 2 MLA 3 MLA 4 MLA 5 MLA 6 MLA 7 introduction, you need to use a specific tactic to help conclude your essay. You can ask a provocative question that keeps your readers thinking about your topic, call your readers to action of some kind, explain the results or consequences of your thesis, offer a warning about your topic, end by giving an interesting and pertinent quotation and commenting on it, tell an interesting story that acts as one final illustration of your thesis, etc. Too Brief Conclusion. Readers need closure, and it’s your job to give it to them; a sentence or two at the end of your essay won’t do this successfully. Look at the suggestions provided in Conclusion 1 for various tactics to help you develop your conclusion. First Page Headings. Your first page heading should look exactly like the one in the MLA sample paper on page 408 of the Writer’s Reference. On the first page of your paper and 1”from the top of the paper, flush with the LEFT margin, place your name, your instructor’s name, the course title, and the date on separate, double-spaced lines. Headers. Your header should be placed ½” from the top of the page flush with the RIGHT margin on every page. It should include your last name, one space, then the page number (see MLA sample paper on page 408 of the Writer’s Reference). If you are not sure how to get your word processing program to format your headers automatically, talk to me! Margins, Line Spacing, and Paragraph Indents. Leave margins of 1” on all sides of the page. Double-space throughout the paper—doublespace your heading on the first page (name, instructor’s name, class, and date) as well. Don’t put “extra” double spaces before or after your title, or in between paragraphs. To indicate you are beginning a new paragraph, indent the first line of each paragraph ½” (5 spaces or 1 tab) from the left margin. See the MLA sample paper on page 408 of the Writer’s Reference. Signal Phrases. Don’t just drop source material into your paper out of nowhere; always use a signal phrase to introduce a quotation, paraphrase or summary. Generally, a signal phrase consists of the author’s name and often provides some context for the source material. Always use present tense in signal phrases (“John Smith states,” not “John Smith stated”). Don’t always use the same verb in your signal phrases—there’s a great list of verbs to use in signal phrases in MLA 3-b on pg. 365. Parenthetical Reference. If you haven’t used your author’s name in the signal phrase and/or your source has page numbers, you will need a parenthetical reference at the end of any quoted, paraphrased, or summarized material. See MLA-4a on pg. 370 for details (there is a great directory on the top of 371 that explains the basic rules for parenthetical reference and the variations on those rules for given sources/situations). Parenthetical Reference/Author Unknown. If your source does not list an author’s name, then a shortened version of the article or webpage title goes in the parenthetical reference (see MLA-4a pg. 372 #3). Punctuation for Parenthetical Reference. Final punctuation always goes after the parenthetical reference, not within the final quotation mark. EX: John Smith states that “only one-third of American pets live a truly MLA 8 MLA 9 MLA 10 MLA 11 satisfying existence” (12). General Works Cited Page Format. Please see the MLA sample Works Cited on page 412 of the Writer’s Reference. Common errors include bolding or underlining the heading, not double-spacing all the entries, not using the hanging indent (first line of each entry flush with left margin, subsequent lines of each entry indented 5 spaces), and not alphabetizing your list of sources. Follow the sample paper to fix any of these problems. Individual Works Cited Entry Format. Use the directory to MLA Works Cited entry models, MLA-4b on pg. 379, to help you find the information you need to fix the format for individual works cited entries. Also very helpful if you’re having trouble understanding the basic order of information that should go in a works cited entry are the “Citation at a Glance” sections in Hacker’s book: books—383, articles in periodicals— 388, short work from a Website—392, and article from a library database—396. NOTE: these four are the most common types of works cited entry formats you will use, so it pays to be familiar with them. “Phantom” Sources. If you have not quoted, paraphrased, or summarized from a source in your essay (that is, you didn’t use it), that source shouldn’t be listed on your Works Cited page. “Works Cited” means the sources you actually used in your paper, not the sources you looked at but didn’t end up using for your paper. Plagiarized Sources (Inadvertent). You know that all direct quotes need to be cited correctly using a signal phrase with the author’s name and a parenthetical reference if necessary. But you also need to cite ANY information you use from a source—a statistic, an idea, a story, a general argument you’ve put in your own words, etc. Putting this information in your own words is called paraphrase or summary (paraphrase if you’ve said it in about the same length as the original, summary if you’ve condensed it down). Just because you put it into your own words doesn’t mean it’s your idea—give credit where credit is due, exactly as you would for a direct quotation. MLA-2a, b, and c (358).