Feedback

advertisement

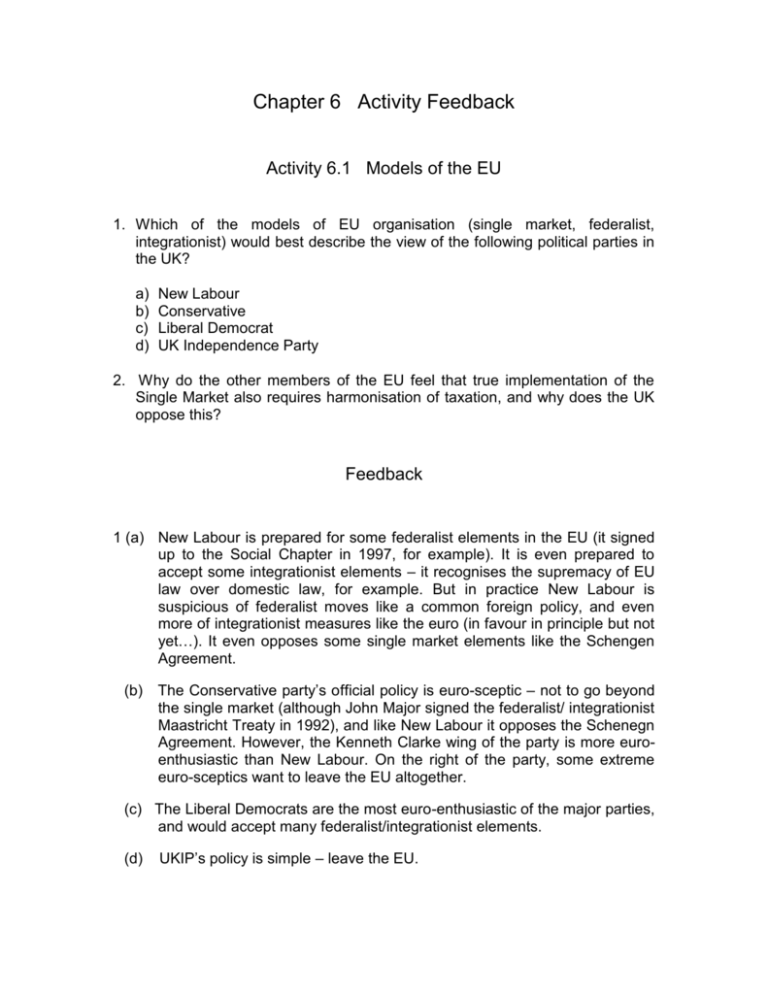

Chapter 6 Activity Feedback Activity 6.1 Models of the EU 1. Which of the models of EU organisation (single market, federalist, integrationist) would best describe the view of the following political parties in the UK? a) b) c) d) New Labour Conservative Liberal Democrat UK Independence Party 2. Why do the other members of the EU feel that true implementation of the Single Market also requires harmonisation of taxation, and why does the UK oppose this? Feedback 1 (a) New Labour is prepared for some federalist elements in the EU (it signed up to the Social Chapter in 1997, for example). It is even prepared to accept some integrationist elements – it recognises the supremacy of EU law over domestic law, for example. But in practice New Labour is suspicious of federalist moves like a common foreign policy, and even more of integrationist measures like the euro (in favour in principle but not yet…). It even opposes some single market elements like the Schengen Agreement. (b) The Conservative party’s official policy is euro-sceptic – not to go beyond the single market (although John Major signed the federalist/ integrationist Maastricht Treaty in 1992), and like New Labour it opposes the Schenegn Agreement. However, the Kenneth Clarke wing of the party is more euroenthusiastic than New Labour. On the right of the party, some extreme euro-sceptics want to leave the EU altogether. (c) The Liberal Democrats are the most euro-enthusiastic of the major parties, and would accept many federalist/integrationist elements. (d) UKIP’s policy is simple – leave the EU. 2 As noted in the previous feedback, tax differentials discourage free movement of goods and hamper competition. For this reason, most members of the EU see tax harmonisation as an essential part of the Single Market. At present the only tax which is harmonised to some extent is VAT, because a portion of VAT receipts forms part of the EU budget. The UK sees tax harmonisation as an unacceptable infringement of UK sovereignty, and if formed one of the UK ‘red lines’ (key issues) in the EU Constitution negotiations. After lengthy argument, the UK succeeded in retaining its veto on taxation within the EU. For the foreseeable future, therefore, tax will not be harmonised. Activity 6.2 EU institutions and power 1. Why do you think that ultimate power in the EU lies with the Council of Ministers rather than the Commission? 2. You work for a FTSE-100 company. Your company is concerned about a possible change in EU social policy which could lead to legislation in the next few years. How can your company influence forthcoming EU decisions on this change? Feedback 1. The Council of Ministers is under the direct control of the governments of member states. In general, the member states have no desire for a fully integrated EU, and so resist any attempt to transfer real power to the Commission. At the same time, the Council of Ministers has some democratic credibility as the member governments themselves have all been elected, while the Commission does not. 2. There are several ways in which a UK company can influence EU policy: Your trade association, or employers;’ body like the CBI or IoD, will either be a member of UNICE, the employers’ social partner, or will have access to it for lobbying purposes. Your local MEP could raise the issue in the European Parliament. This will at least ensure that the issue receives a public airing. Although the Parliament does not have direct decision-making powers, the Commission is sensitive to its opinions. You could lobby the relevant UK government department, probably the DTI, which will have representation on the Council of Ministers when the final decisions are taken. Activity 6.3 EU enlargement What do you think is the likely impact of EU enlargement on your own organisation or sector? Feedback Your own organisation or sector could be affected in the following ways: Well-educated migrants from the accession states could fill skills gaps in the UK. The ex-communist entrants on the whole had excellent education systems, and the typical migrant is young, probably English-speaking, and with a tertiary education (contrary to the impression put out by the eurosceptic tabloids!). The new entrants will represent export opportunities. Some work could be outsourced to the new entrants. EU-15 markets will be opened up to imports from the new members. Activity 6.4 The EU constitution The opinion polls after the announcement of agreement on the Constitution suggested that there would have been a two to one majority against it in a UK referendum. Why do you think this is so? Feedback There are some genuine fears that the UK has given away too much sovereignty in the Constitution, but it is important to remember that significant elements of the media in the UK are virulently eurosceptic, led by the Sun and the Daily Mail. These newspapers, and others, whipped up considerable hysteria in the period just before expansion in May 2004 with a fear that the UK would be ‘swamped’ by an immediate flood of immigrants from the new member states in Eastern Europe. A Leading Article in The Guardian on June 21 (Leading Article, 2004) pointed out that the same poll which showed a 2:1 majority against the Constitution also showed that if their anxieties were met, voters would support the Constitution, albeit by a narrow majority. Crucially, their anxieties included fears that the EU would be able to increase taxes in Britain, that the UK would have to join the eurozone, that the British passport would be replaced by an EU one, and that Britain would lose its seat on the Security Council to the EU. None of these are true. This suggests that opposition to the Constitution is a combination of genuine concern over a perceived loss of sovereignty, xenophobia whipped up by the eurosceptic press, a fear of the unknown, and ignorance. Activity 6.5 Is comparative advantage good for you? The theory of comparative advantage suggests that everyone gains from free trade. Why then do so many countries protect their own domestic industries? Feedback There are a number of objections to free trade: The law of comparative advantage encourages countries to specialise in a small number of products – bananas in the Caribbean, cocoa in Ghana, for example (this is an example of globalisation, which we will analyse later in this chapter). This makes these economies very vulnerable, both to a downturn in the market and to natural disasters, like disease or hurricanes. Comparative advantage works superbly in a grossly over-simplified model of the world economy – particularly when we only consider two countries. In practice, international trade involves many players, not just two. For example, the Windward Islands do have a comparative advantage in bananas compared with the UK, but Honduras has an even bigger comparative advantage (see the case study on the banana war). Free trade is static – it tends to freeze the world economy at one point in time. Free trade suits the dominant industrial economies at any one time, as it denies developing economies the opportunity to develop their own industries. They are forced to specialise in extractive or agricultural sectors where they have a current comparative advantage. Protection thus tends to be in the interests of developing economies. In the early eighteenth century, the UK put tariffs on imports of Indian cotton goods, thereby destroying the Indian cotton industry, and allowing the growth of the UK cotton industry to world dominance. Once UK industry was dominant in the early nineteenth century, the UK switched to free trade, while countries like the US and Germany built up their industries behind protective barriers. The pattern continues today – in the late twentieth century, the US favoured free trade, while China built up a highly competitive industrial sector behind protective barriers. In developed countries, weak industries will press for protection from foreign competition. Although there are strong economic arguments against this, there may be good social arguments in favour. Thus the rapid destruction of the coal industry in the UK in the 1980s may have made economic sense, but it caused enormous social disruption through the decimation of long-standing mining communities. In a recession, there is sometimes a temptation for countries to cheat on free trade, by selling their products overseas at below their cost of production. This is known as dumping, and is against the rules of the WTO. Member states are therefore permitted to impose tariffs on goods which they can prove have been dumped. Activity 6.6 Debt relief Can you put forward any arguments against either the principle or the practice of debt relief for the Third World? Feedback One objection to the principle of debt relief is the concept of moral hazard, which we discussed earlier in this chapter. If poor countries know that their debts are likely to be cancelled, they may become more irresponsible in running them up in the first place. As the for the practical application of the debt relief, except for the extremely slow progress of debt relief, and the onerous terms attached to it, the main problem here is one of arbitrary definition. The HIPC initiative only apples to 52 countries, and excludes some countries which most people would define as extremely poor, including Bangladesh and Haiti. Activity 6.7 Why do people hate the WTO and globalisation? Throughout the west, there is deep suspicion, on many cases verging on hatred, of the progress of globalisation in general, and the activities of the WTO in particular. Why do you think this is? Feedback Globalisation and the WTO are opposed for many reasons: There is a perception that it operates in the interests of huge, global corporations, who are only interested in their own profit. This view tends to be supported by the Banana War, when the interests of the American banana barons won out at the expense of small Caribbean producers. Big corporations can afford the best lawyers, and they also represent the status quo in terms of the distribution of economic power. That it is destroying democracy by imposing the will of unelected elites within the international financial institutions on the rest of the world. The IMF and the World Bank make no pretence to be democratic. The WTO is democratic, in the sense that it is one country, one vote, but it is still seen to be undemocratic, and dominated by faceless and unaccountable power brokers. That it undermines workers rights and environmental protection by encouraging a ‘race to the bottom’ between governments competing for jobs. Thus British textiles are made in Mauritius and Bangladesh, footballs in Pakistan, etc, often in conditions and for wages which would be totally unacceptable in the West. However, there is a positive side to this. Multinational companies operating in the Third World are usually better employers than locally-owned sweatshops, and the countries involved do benefit from the exports of textiles. That it is destroying British jobs. In a free trade world economy, jobs will go where there is a comparative advantage. Thus many British manufacturing jobs are moving to the Third World, where the population is highly educated but cheap. In the long run, this will benefit both the UK and India, although there will be short-term disruption. That it harms the poor. Certainly insensitive IMF and World Bank policies during the 1990s did harm the poor in developing countries, who were forced to pay for basic social and welfare services. This practice has been heavily criticised, and the IMF/World Bank is in the process of becoming less interventionist. That globalisation is basically Americanisation. Although many people in the Third World positively like Coke and McDonalds, there is widespread resentment at the spread of American culture, brands, values and power, particularly within the Islamic world. Activity 6.8 Globalisation and your organisation What impact, if any, has globalisation had on your own organisation? Feedback There is likely to be both an economic impact on your organisation, and a professional impact on your HR role. If you work for a large public company, the shares of your company will probably be traded in New York as well as in London, and increasingly share prices in the UK follow those in the US. If you work in the public sector, the impact of globalisation is likely to be more indirect, but most parts of the public sector have experienced the worldwide pressure towards privatisation, public-private partnerships and best value. We also all feel the impact of globalisation as the world economy becomes more integrated, and at the same time more vulnerable to random shocks, whether they are the financial crisis in Asia in 1997, or the terrorist attacks on the US in 2001. If there is a major recession in the US, there is virtually no chance of the UK avoiding it. As an HR professional, you are likely to experience pressures to outsource. (see the Call Centre Case Study). You may thus be called on to evaluate labour market conditions, local employment law, and cultural norms, in places like Bangalore or Warsaw. At the same time, particularly in London and other big cities, many skilled jobs are being filled by foreign nationals. This can only increase now that membership of the EU has expanded. You will increasingly need to be aware of requirements for work permits, and regulations on the employment on asylum seekers. Activity 6.9 Jaguar-Land Rover: a cultural football Few companies have been through as many different international owners as Jaguar-Land Rover. Both Jaguar and Land Rover became part of British Leyland (BL) in 1968. In 1975 BL was nationalised, and in 1988 it was sold to British Aerospace (BAe). In practice Jaguar and Land Rover, along with the rest of the group, was managed by Honda under a strategic alliance with BAe. In 1994, the whole group was sold to BMW, which itself sold out to Ford in 2000. Finally, in 2008, Ford sold Jaguar and Land Rover to Tata. Land Rover has thus successively been under British (both private and public), Japanese, German, American and Indian management. The Dutch guru Geert Hofstede has identified what he calls his cultural dimensions, which he says accurately describe national characters. His dimensions are: Power Distance (PD). The extent to which societies accept that power is and should be distributed unequally. Organisationally, high Power Distance will lead to hierarchical organisations with large wage differentials. Individualism (IDV). The degree to which individuals are integrated into groups. Collectivist societies with a low individualism score will have a high level of employment security and commitment to staff. Masculinity/Femininity (M/F). Masculine societies are assertive and competitive, with high levels of organisational conflict. Uncertainty avoidance (UA). The degree to which people feel comfortable in ambiguous situations. Low uncertainty avoidance is reflected in informal, unstructured organisations. Long term orientation (LTO). In organisations this will be reflected in shortterm profit maximisation, versus long-term growth. The following table summarises those of Hofstede’s findings which are relevant to Jaguar-Land Rover: Country PD IDV M/F UA LTO United Kingdom Japan Germany United States India Low Medium Low Low High High Low Medium High Medium Medium High Medium Medium Medium Low High Medium Low Low Low High Low Low Medium Source: Hofstede G, 2009 www.geert-hofstede.com/hofstede (accessed 14 October 2009). To some extent, the above table is reflected in attitudes to quality at Jaguar-Land Rover. Under British management, quality was a low priority – most of the time the group was struggling for survival. Honda brought in a high priority for quality, with the emphasis placed on the ‘soft’ aspects – total quality management, kaizen (continuous improvement), quality circles, just in time - and a realisation that the pay-off from quality would be long-term. BMW was also concerned with quality, with a shorter-term orientation and a more top-down approach, while Ford concentrated on ‘hard’ aspects of quality, such as Six Sigma. It is yet to be seen what Tata’s approach will be, but evidence on Tata’s management style suggests a high commitment to quality (see Section ??). It is important to bear in mind that Hofstede’s approach has been heavily criticised. One key criticism is that his basic research is very old, carried out between 1967 and 1973, and originally based solely on (mainly male) employees of IBM. What other criticisms can you make of Hofstede’s approach, (a) in general and (b) in relation to Jaguar-Land Rover? (You will find Marchington and Wilkinson, Human Resource Management at Work, 4th ed, pages 29–31 useful.) Feedback Marchington and Wilkinson point out a number of flaws in Hofstede’s approach: Many of the national samples in his research were very small – only 37 in Pakistan, for example. The research ignores differences within countries – between New York or San Francisco on the one hand, and the deep south of the US on the other, or between England and Scotland. The averages can hide much greater variation within countries, and so individuals vary much more within countries than between countries. It is theoretically possible that a country might contain two extreme but opposed cultures, but an average would cancel out these differences and produce a middle of the road result which is not representative. Research cited by Marchington and Wilkinson suggests that Hofstede’s results only explain between 2–4 per cent of the variance between countries. In practice national cultures can evolve - they are not frozen in time. Monocultural Britain in the 1950s was not the same country as multi-cultural Britain in the 2000s. The research ignores the impact of corporate culture. A strong organisation can easily have its own culture which is very different from the predominant national culture. IBM itself is well known for having a strong corporate culture, which permeates its activities throughout the world. (see also Chiang 2005) Chiang F, (2005), A critical examination of Hofstede’s thesis and its application to international reward management, International Journal of Human Resource Management, vol. 16 issue 9. Turning to the corporate level, there are some contradictions in the data. Ford, for example, comes from a national culture (the US) which stresses shorttermism, but Ford is well known for taking a long-term view (which helps to explain why it came through the 2008–9 recession relatively unscathed, while its US rivals General Motors and Chrysler both went into liquidation. Another example is Honda (and Japanese companies in general). They stress the individual role in maintaining high levels of quality, but Hofstede’s Japanese cultural model suggests that they should be low on individualism. Seminar Activity Polish plumbers On 1 May 2004, ten new members joined the EU. Eight of these, known as the A8, came from Central and Eastern Europe, the biggest of these being Poland, with a population of about 38.5 million. The UK already had a significant Polish minority, the descendants of the Free Poles who had fought on the Allied side in the war, and who had decided not to go back to a Communist Poland. In the 2001, census, there were nearly 61,000 people who had been born in Poland, with a third of these living in London (BBC nd). With their descendants, they made up a population of Polish ancestry of about a quarter of a million. Under the EU rules on free movement, people from the A8 countries had the right to come to other EU countries, but this did not necessarily extend to the right to work. As part of the accession arrangements, the 15 ‘old’ EU countries had the right to impose restrictions on work for A8 citizens for up to seven years. Only Sweden allowed A8 citizens an unrestricted right to work. The UK and Ireland granted them right to work, but no right to unemployment benefit until they had worked continuously for a year. It was forecast at the time of accession that 13,000 A8 workers a year would come to the UK. However, this has proven to be a gross under-estimate. Denis MacShane, who was Europe minister at the time, claimed that the original figure was based on all 15 old EU members opening their doors to A8 workers. (MacShane 2006). Although it is clear that many more A8 workers, particularly Poles, are working in the UK than originally thought, nobody really knows how many. As Poles and other A8 citizens can enter the EU without visa, there is no way to telling how many of those who enter the country intend to work, and how many are just passing through. The Office for National Statistics carries out random interviews on arrivals to the UK and on this basis estimates that 56,000 Poles entered the UK to work in 2005. However, the Department of Work and Pensions says that 170,000 Poles applied for National Insurance numbers in 2005 (Doward and McKenna 2007). The other main source of information on numbers is the Worker Registration Scheme (WRS), under which A8 workers are encouraged to register. This is not compulsory, is not required for the self-employed, and costs £75. There is also no requirement to deregister if a worker leaves the UK. In May 2005, the BBC reported that 176,000 had registered by March 2005. Of these 82 per cent were aged between 18 and 34, 96 per cent were working full time and a third may have been working illegally in the UK before accession and merely regularising their position. Poland was the biggest provider, with 56 per cent of the total, followed by Lithuania with 15 per cent, and Slovakia with 11 per cent. (BBC 2005). This is not surprising, as Poland had by far the biggest population of the A8 countries, it had 20 per cent unemployment, wages one-sixth of those in the UK, and a well-educated population, many of whom spoke English. By January 2007, 579,000 had registered under the WRS, of whom 63 per cent were from Poland. The anti-immigration pressure group claimed that this was an under-estimate, and that the true figure was nearer 600,000, although they admitted that many of these will have left the country (Migration Watch 2007). By December 2007 the number registered had increased to 750,000. (House of Lords 2008). Some figures are also available from the Polish end of the migration. In 2004, the year of accession, there were fewer movements of Poles out of the country than in 2003 (27.2 million compared with 38.6 million) (Iglicka 2005). However, there is no way of telling how many of these were going out of Poland to work, or, perhaps, on day trips to Germany or the Czech Republic. What may be significant, however, is that the number of those leaving by air increased by 37 per cent in 2004 to 1.89 million. Official emigration in 2004 was also lower than in 2003, and only 543 Poles officially emigrated to the UK, compared with 12,646 to Germany. Rumours and urban myths abound of the number of Poles in the UK. There are said to be 10,000 in Slough, 15,000 in Boston, Lincolnshire, 3,000 in Crewe (Doward and McKenna 2007). According to some stories, every other plumber in the UK is now Polish, although according to WRS figures there are only about 100 Polish plumbers registered. Remember, though, that the self-employed do not have to register. Remember also that despite the myths, most Polish and other A8 immigrants are not plumbers. Among the A8 immigrants, 24 per cent work in distribution, hotels and restaurants, 21 per cent in manufacturing, 14 per cent in construction, and a significant but unstated proportion in agriculture and food processing (House of Lords 2008, 18). The plain truth is nobody really has any idea how many Poles are working in Britain. It is thought that most Polish and other A8 workers come to the UK with every intention of going back to Poland, and, unlike other immigrant groups, going back is very easy and cheap – as cheap as £10 on a Ryanair flight. When questioned by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation immediately after accession, only six percent said they intended to stay in the UK permanently. A year later, this had risen to 29 per cent. (Spencer et al 2007). In September 2007, 62 per cent of those arriving in the previous 12 months said they intended to stay for less than one year (House of Lords 16), although the experience of other immigrant groups suggests that more will stay than initially expected to. The best estimate is probably that at any one time, there are about 200,000–250,000 Polish workers in the UK at any one time, which approximately doubles the figure of Polish descent in 2001. We will not have any really accurate figures until the 2011 census. Questions 1. What do you think is the likely economic and social impact of the influx of Polish and other A8 workers into the UK? 2. How can trade unions respond to the issues raised by the influx of Polish workers? Feedback 2. John Philpott and Gerwyn Davies of the CIPD estimated the impact of eastern European immigration on the UK in 2006 (Philpott and Davies 2006). Their analysis was generally favourable. They quoted the Home Office – ‘contributing to the success of the economy while making very few demands on out welfare state or public services’, and the CBI, ‘Immigration has been a success story - benefiting the economy, businesses and the people who have come.’ The Poles are nearly all young, nearly all single, and nearly all in work. They thus pay taxes and National Insurance, but make few demands on the welfare services. They don’t have children, so there are no education costs, they are healthy, so low NHS costs, and they are way off pension age. They also fill skills shortages in the UK, particularly in agriculture, construction and the hospitality industry. Because they are mostly paid at or near minimum wage, this has held the UK inflation rate down. As a result, interest rates are estimated to have been 0.5 per cent lower and output 0.2 per cent higher than otherwise would have been the case. However, Migration Watch points out that the net benefit per head of the population is very small – on one estimate 4p per person per week (Migration Watch 2007), and recent research carried out for the House of Lords also suggests that the benefit has been small. The NIESR estimated that the impact on GDP per head is negative in the short term (up to four years), but slightly positive in the long tun (up by 0.3 per cent by 2015). A8 immigration has also lowered the wage rates for those in the lowest paid jobs. (House of Lords, 26-27) Unlike previous waves of immigration, the Poles have not predominantly gone to London, West Yorkshire and the West Midlands. Only 21 per cent are in London, and 40 per cent in the rural counties of Lincolnshire, Norfolk, Kent and Sussex, with significant concentrations in Southampton, northern Scotland and west Wales. The TUC has pointed out that they run the risk of exploitation by rural gang-masters, and that they should be encouraged to join unions for their own protection (Philpott and Davies 2006). A8 migrants generally are highly regarded by employers. They are rated as more productive than non-migrants by 43 per cent of employers (only 4 per cent think they are worse). Figures for reliability are 38 and 6, for absence 37 and 6, and for quality of work 25 and 1. These figures suggest that A8 migrants are underpaid for the work they do, supported by the fact that almost 80 per cent of A8 migrants earn between £4.50 and £5.99 an hour (Philpott 2007). Towns with high concentrations of A8 workers are complaining about pressure on local facilities, particularly housing, and this undoubtedly true. Housing pressure will increase rents and house prices. However, the pressure may not be as great as it seems at first sight. The biggest employers of A8 workers are agriculture and hospitality, both of which are likely to provide live-in accommodation. As they are single, the A8 workers are also likely to multiply occupy houses. MacShane points out that we must also put the immigration in perspective. A8 migrants make up less than half a percent of the UK workforce. There are many more British emigrants in the EU – 750,000 in Spain, 500,000 in France – and there are complaints in these countries about the Brits pushing up house prices and clogging up the healthcare system (MacShane 2006). 2. A number of initiatives have been taken by trade unions to respond to the needs of Polish workers in the UK: Amicus is providing advice for Polish workers in Bradford, covering housing as well as employment issues. The Vulnerable Workers Project, run by the TUC and funded by the Department for Business and Enterprise, is providing free training on employment rights for Polish workers in London, after finding that over a quarter had problems with getting paid properly. Under an agreement between the GMB and the Polish union Solidarnosc (Solidarity), Polish workers will be told of their UK employment rights before they leave Poland, and will be encouraged to join the GMB. Two full-time GMB Organisers in the East Midlands who are themselves migrant workers recruit and organise migrant labour in agriculture and food processing. The GMB and Unison hosted three Polish bands at the Glastonbury Festival in both 2007 and 2008.