Scoliosis - Open eClass

advertisement

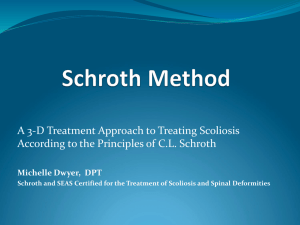

Scoliosis Scoliosis (from Greek: skoliōsis meaning from skolios, "crooked") is a medical condition in which a person's spine is curved from side to side. Although it is a complex three-dimensional deformity, on an X-ray, viewed from the rear, the spine of an individual with scoliosis may look more like an "S" or a "C" than a straight line. Scoliosis is typically classified as either congenital (caused by vertebral anomalies present at birth), idiopathic (cause unknown, subclassified as infantile, juvenile, adolescent, or adult, according to when onset occurred), or neuromuscular (having developed as a secondary symptom of another condition, such as spina bifida, cerebral palsy, spinal muscular atrophy, or physical trauma). Contents o o o o o o 1 Signs and symptoms 1.1 Associated conditions 2 Cause 3 Diagnosis 3.1 Genetic testing 4 Management 4.1 Physiotherapy 4.2 Occupational Therapy 4.2.1 Self-care 4.2.2 Productivity 4.2.3 Leisure 4.3 Bracing 4.4 Surgery 4.4.1 Spinal fusion with instrumentation 4.4.2 Thoracoplasty 4.4.3 Complications 4.4.4 Surgery without fusion 5 Prognosis 6 Epidemiology o o 7 Society and culture 7.1 Scoliosis Research Society 7.2 About Skolyoz Destek Grubu 8 See also 9 References Signs and symptoms Patients having reached skeletal maturity are less likely to have a worsening case. Some severe cases of scoliosis can lead to diminishing lung capacity, putting pressure on the heart, and restricting physical activities. The signs of scoliosis can include: Uneven musculature on one side of the spine A rib prominence and/or a prominent shoulder blade, caused by rotation of the ribcage in thoracic scoliosis Uneven hips/leg lengths Slow nerve action (in some cases) Associated conditions Scoliosis is sometimes associated with other conditions such as Ehlers–Danlos syndrome (hyperflexibility, "floppy baby" syndrome, and other variants of the condition), Charcot–Marie– Tooth disease, Prader–Willi syndrome, kyphosis, cerebral palsy, spinal muscular atrophy, muscular dystrophy, familial dysautonomia, CHARGE syndrome, Friedreich's ataxia, Fragile X syndrome[2][3], proteus syndrome, spina bifida, Marfan's syndrome, neurofibromatosis, connective tissue disorders, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, hemihypertrophy, and craniospinal axis disorders (e.g., syringomyelia, mitral valve prolapse, Arnold– Chiari malformation), and Amniotic Band Syndrome (ABS). Scoliosis associated with known syndromes such as Marfan's or Prader–Willi is often sub-classified as "syndromic scoliosis." Cause It has been estimated that approximately 65% of scoliosis cases are idiopathic, approximately 15% are congenital and approximately 10% are secondary to a neuromuscular disease.[4] Idiopathic scoliosis is a condition which lasts a lifetime, but it does not increase the risk of mortality. In adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, there is no clear causal agent and it is generally believed to be multifactorial, although genetics are believed to play a role.[6] Various causes have been implicated, but none of them have consensus among scientists as the cause of scoliosis, though the role of genetic factors in the development of this condition is widely accepted. Still, at least one gene, notably CHD7, has been associated with the idiopathic form of scoliosis. In some cases, scoliosis exists at birth due to a congenital vertebral anomaly. Scoliosis secondary to neuromuscular disease may develop during adolescence, such as with tethered spinal cord syndrome. Scoliosis often presents itself, or worsens, during the adolescence growth spurt and is more often diagnosed in females versus males. Diagnosis Patients who initially present with scoliosis are examined to determine whether there is an underlying cause of the deformity. During a physical examination, the following is assessed: Skin for café au lait spots, indicative of neurofibromatosis The feet for cavovarus deformity Abdominal reflexes Muscle tone for spasticity During the exam, the patient is asked to remove his or her shirt and bend forward. This is known as the Adams Forward Bend Test and is often performed on school students. If a prominence is noted, then scoliosis is a possibility and the patient should be sent for an X-ray to confirm the diagnosis. As an alternative, a scoliometer may be used to diagnose the condition.[11] The patient's gait is assessed, and there is an exam for signs of other abnormalities (e.g., spina bifida as evidenced by a dimple, hairy patch, lipoma, or hemangioma). A thorough neurological examination is also performed. It is usual, when scoliosis is suspected, to arrange for weightbearing full-spine AP/coronal (front-back view) and lateral/sagittal (side view) X-rays to be taken. This is to assess the scoliosis curves and the kyphosis and lordosis, as these can also be affected in individuals with scoliosis. Full-length standing spine X-rays are the standard method for evaluating the severity and progression of the scoliosis, and whether it is congenital or idiopathic in nature. In growing individuals, serial radiographs are obtained at 3–12 month intervals to follow curve progression, and, in some instances, MRI investigation is warranted to look at the spinal cord. The standard method for assessing the curvature quantitatively is measurement of the Cobb angle, which is the angle between two lines, drawn perpendicular to the upper endplate of the uppermost vertebrae involved and the lower endplate of the lowest vertebrae involved. For patients with two curves, Cobb angles are followed for both curves. In some patients, lateral-bending X-rays are obtained to assess the flexibility of the curves or the primary and compensatory curves. Genetic testing Genetic testing for AIS, which became available in 2009 and is still under investigation, attempts to gauge the likelihood of curve progression. Through a genome-wide association study, geneticists have identified single nucleotide polymorphism markers in the DNA that are significantly associated with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Fifty-three genetic markers have been identified. Scoliosis has been described as a biomechanical deformity, the progression of which is dependent on asymmetric forces otherwise known as the Heuter-Volkmann law.[12][13] Management The traditional medical management of scoliosis is complex and is determined by the severity of the curvature and skeletal maturity, which together help predict the likelihood of progression. The conventional options are, in order: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Observation Physical Therapy Occupational Therapy Chiropractic or Osteopathic Therapy Casting (EDF) Bracing Surgery A growing body of scientific research testifies to the efficacy of specialized treatment programs of physical therapy, which may include bracing.[14] Debate in the scientific community about whether chiropractic and physical therapy can influence scoliotic curvature is partly complicated by the variety of methods proposed and employed: Some are supported by more research than others. Physiotherapy The Schroth method is a noninvasive, physiotherapeutic treatment, which has been used successfully in Europe since the 1920s. Originally developed in Germany by scoliosis sufferer Katharina Schroth, this method is now taught to scoliosis patients in clinics specifically devoted to Schroth therapy in Germany, Spain, England, and North America. The method is based upon the concept of scoliosis as resulting from a complex of muscular asymmetries (especially strength imbalances in the back) that can be at least partially corrected by targeted exercises.[17] The Schroth method has proven effective at reversing abnormal scoliotic curvatures by an average of 10% in 4- to 6-week inpatient programs,[18] and by 30% or more in an out-patient program over a period of a year.[19] One study of nearly 200 adolescent Schroth patients found no curve progression three years following the in-patient program.[20] Several studies have documented the Schroth method's efficacy in substantially reducing or eliminating pain, which tends to be a problem, in particular, for adults.[21] Small curvatures between 15 and 20° during growth may be treated with the physio-logic-program,[22] curvatures between 20 and 30° during growth spurt with "3D-made-easy". This program has been tested in the environment of in-patient treatment as well.[23][24] In curvatures exceeding 30°, a combination of the methods described together with the Schroth program may be helpful,[25] and a specialized centre with trained and certified staff should be taken into account. Out-patient rehabilitation treatments today may reach the same outcome as in-patient programs.[26] Outpatient programs may be successful when pattern-specific programs are provided. A certain intensity is necessary to allow the very best compliance with conservative treatment, and to acquire strategies for coping with scoliosis and with the conservative treatment. The indications for treatment depend on degree of curvature, maturity of the patient, and the individual curve pattern. While evidence supporting such conservative, non-invasive treatments is weak, today conservative management of scoliosis can be regarded as being evidence-based; no substantial evidence has been found to support surgical intervention. Kyphosis Kyphosis (Greek - kyphos, a hump), also called roundback or Kelso's hunchback, is a condition of over-curvature of the thoracic vertebrae (upper back). It can be either the result of degenerative diseases (such as arthritis), developmental problems (the most common example being Scheuermann's disease), osteoporosis with compression fractures of the vertebrae, and/or trauma. In the sense of a deformity, it is the pathological curving of the spine, where parts of the spinal column lose some or all of their lordotic profile. This causes a bowing of the back, seen as a slouching posture. While most cases of kyphosis are mild and only require routine monitoring, serious cases can be debilitating. High degrees of kyphosis can cause severe pain and discomfort, breathing and digestion difficulties, cardiovascular irregularities, neurological compromise, and in the more severe cases, significantly shortened life-spans. These types of high end curves typically do not respond well to conservative treatment, and almost always warrant spinal fusion surgery, which can successfully restore the body's natural degree of curvature. The Cobb angle is the preferred method of measuring kyphosis. Contents o o o o 1 Classification 2 Treatments 2.1 Orthosis (brace) 2.2 Specialised physical therapy 2.3 Surgery 2.4 Complications 3 See also 4 References 5 External links Classification There are several kinds of kyphosis (ICD-10 codes are provided): Postural kyphosis (M40.0), the most common type, normally attributed to slouching, can occur in both the old[1] and the young. In the young, it can be called 'slouching' and is reversible by correcting muscular imbalances. In the old, it may be called 'hyperkyphosis' or 'dowager’s hump'. About one third of the most severe hyperkyphosis cases have vertebral fractures.Otherwise, the aging body tends towards a loss of musculoskeletal integrity, and kyphosis can develop due to aging alone. Scheuermann's kyphosis (M42.0) is significantly worse cosmetically and can cause varying degrees of pain, and can also affect different areas of the spine (the most common being the mid-thoracic area). Scheuermann's disease is considered a form of juvenile osteochondrosis of the spine, and is more commonly called Scheuermann's disease. It is found mostly in teenagers and presents a significantly worse deformity than postural kyphosis. A patient suffering from Scheuermann’s kyphosis cannot consciously correct posture. The apex of the curve, located in the thoracic vertebrae, is quite rigid. The patient may feel pain at this apex, which can be aggravated by physical activity and by long periods of standing or sitting. This can have a significantly detrimental effect on their lives, as their level of activity is curbed by their condition; they may feel isolated or uneasy amongst peers if they are children, depending on the level of deformity. Whereas in postural kyphosis, the vertebrae and disks appear normal, in Scheuermann’s kyphosis, they are irregular, often herniated, and wedge-shaped over at least three adjacent levels. Fatigue is a very common symptom, most likely because of the intense muscle work that has to be put into standing and/or sitting properly. The condition appears to run in families. Most patients who undergo surgery to correct their kyphosis have Scheuermann's disease. Congenital kyphosis (Q76.4) can result in infants whose spinal column has not developed correctly in the womb. Vertebrae may be malformed or fused together and can cause further progressive kyphosis as the child develops. Surgical treatment may be necessary at a very early stage and can help maintain a normal curve in coordination with consistent follow ups to monitor changes. However, the decision to carry out the procedure can be very difficult due to the potential risks to the child. A congenital kyphosis can also suddenly appear in teenage years, more commonly in children with cerebral palsy and other neurological disorders. Nutritional kyphosis can result from nutritional deficiencies, especially during childhood, such as vitamin D deficiency (producing rickets), which softens bones and results in curving of the spine and limbs under the child's body weight. Gibbus deformity is a form of structural kyphosis, often a sequela to tuberculosis. Post-traumatic kyphosis (M84.0) after untreated or not treated effectively vertebral fractures Treatments Orthosis (brace) Modern brace for the treatment of a thoracic kyphosis. The brace is constructed using a CAD / CAM device. At this stage, this is the only CAD / CAM brace designed to treat a thoracic kyphosis. It is called kyphologic. Body braces showed benefit in a randomised controlled trial. The Milwaukee brace is one particular body brace that is often used to treat kyphosis in the US. Modern CAD / CAM braces are used in Europe to treat different types of kyphosis. These are much easier to wear and have better in-brace corrections than reported for the Milwaukee brace. Since there are different curve patterns (thoracic, thoracolumbar and lumbar) different types of braces are in use. The advantages / disadvantages of different braces are discussed in a recent review article.[7] Modern brace for the treatment of a lumbar / thoracolumbar kyphosis. The brace is constructed using a CAD / CAM device. At this stage this brace is the only CAD / CAM brace designed to treat a lumbar kyphosis and is called physio-logic brace. Restoration of the lumbar lordosis is the major aim. Specialised physical therapy In Germany, a standard treatment for both Scheuermann's disease and lumbar kyphosis is the Schroth method, a system of physical therapy for scoliosis and related spinal deformities. Surgery Surgical treatment can be used in severe cases. In patients with progressive kyphotic deformity due to vertebral collapse, a procedure called a kyphoplasty may arrest the deformity and relieve the pain. Kyphoplasty is a minimally invasive procedure, requiring only a small opening in the skin. The main goal is to return the damaged vertebra as close as possible to its original height. Complications The risk of serious complications from spinal fusion surgery for kyphosis is estimated to be 5%, similar to the risks of surgery for scoliosis. Possible complications may be inflammation of the soft tissue or deep inflammatory processes, breathing impairments, bleeding, and nerve injuries. According to the latest evidence, the actual rate of complications may be substantially higher. Even among those who do not suffer serious complications, 5% of patients require reoperation within five years of the procedure, and in general it is not yet clear what to expect from spine surgery in the long-term. Taking into account that signs and symptoms of spinal deformity cannot be changed by surgical intervention, surgery remains to be a cosmetic indication. Unfortunately, the cosmetic effects of surgery are not necessarily stable. In case one decides to undergo surgery, a specialised centre should be preferred. 1. . Lordosis Lordosis is a medical term used to describe an inward curvature of a portion of the lumbar and cervical vertebral column. Two segments of the vertebral column, namely cervical and lumbar, are normally lordotic, that is, they are set in a curve that has its convexity anteriorly (the front) and concavity posteriorly (behind), in the context of human anatomy. When referring to the anatomy of other mammals, the direction of the curve is termed ventral. Curvature in the opposite direction, that is, apex posteriorly (humans) or dorsally (mammals) is termed kyphosis. Excessive or hyperlordosis is commonly referred to as swayback or saddle back, a term that originates from the similar condition that arises in some horses. A major factor of lordosis is anterior pelvic tilt, when the pelvis tips forward when resting on top of the femurs. Cause A consequence of the normal lordotic curvatures of the vertebral column, (also known as secondary curvatures) is that there are differences in thickness between the anterior and posterior part of the intervertebral disc. Lordosis may also increase at puberty sometimes not becoming evident until the early or mid-20s. Imbalances in muscle strength and length are also a cause, such as weak hamstrings, or tight hip flexors (psoas). Excessive lordotic curvature is also called hyperlordosis, hollow back, saddle back, and swayback. Common causes of excessive lordosis include tight low back muscles, excessive visceral fat, and pregnancy. Although lordosis gives an impression of a stronger back, incongruently it can lead to moderate to severe lower back pain. Rickets, a vitamin D deficiency in children, can cause lumbar lordosis. Treatment Lordosis of the lower back may be treated by strengthening the hip extensors on the back of the thighs, and by stretching the hip flexors on the front of the thighs. Too much importance has been attributed to the abdominal muscles in maintaining a neutral spine position. They may help by pushing the internal organs against the spine hence alleviating the lumbar curvature but they can't rotate the pelvis backward while in a standing position. Also the lumbar erector spinae is not able to rotate the pelvis forward while standing, hence its strengthening is not to be avoided during lordosis treatment. Only the muscles on the front and on the back of the thighs can rotate the pelvis forward or backward while in a standing position because they can discharge the force on the ground through the legs and feet. Abdominal muscles and erector spinae can't discharge force on an anchor point while standing, unless one is holding his hands somewhere, hence their function will be to flex or extend the torso, not the hip. Back hyperextensions on a Roman chair or inflatable ball will strengthen all the posterior chain and will treat lordosis. So too will stiff legged deadlifts and supine hip lifts and any other similar movement strengthening the posterior chain without involving the hip flexors in the front of the thighs. Abdominal exercises could be avoided altogether if they stimulate too much the psoas and the other hip flexors. Strengthening of the hip extensors, which are on the back of the thighs, and optionally stretching of the hip flexors, which are on the front of the thighs, will be enough to treat a lordosis in quite a short time. Anti-inflammatory pain relievers may be taken as directed for short-term relief. Physical therapy effectively treats 70% of back pain cases due to scoliosis, kyphosis, lordosis, and bad posture. Measurement and diagnosis of lumbar lordosis can be difficult. Obliteration of vertebral end-plate landmarks by interbody fusion may make the traditional measurement of segmental lumbar lordosis more difficult. Because the L4-L5 and L5-S1 levels are most commonly involved in fusion procedures, or arthrodesis, and contribute to normal lumbar lordosis, it is helpful to identify a reproducible and accurate means of measuring segmental lordosis at these levels.[2][3] Hypo-lordosis is more common than Hyper-lordosis. Hypolordosis can be corrected non-surgically through rehabilitation exercises. Many different techniques exist to accomplish this correction. These exercises, if done correctly, may reduce symptoms in those with the typical presentation in 3-6 months. The type of practitioner that usually offers this type of treatment is usually a Chiropractor, some physical therapists do this type of rehab but it is not very common.[4][5] In non-human animals Lordosis is seen in non-humans, in particular horses and other equines. Usually called "swayback," soft back, or low back, it is an undesirable conformation trait. Swayback is caused in part from a loss of muscle tone in both the back and abdominal muscles, plus a weakening and stretching of the ligaments. As in humans, it may be influenced by bearing young; it is sometimes seen in a broodmare that has had multiple foals. However, it is also common in older horses whose age leads to loss of muscle tone and stretched ligaments. It also occurs due to overuse or injury to the muscles and ligaments from excess work or loads, or from premature work placed upon an immature animal. Equines with too long a back are more prone to the condition than those with a short back, but as a longer back is also linked to smoother gaits, the trait is sometimes encouraged by selective breeding. It has been found to have a hereditary basis in the American Saddlebred breed, transmitted via a recessive mode of inheritance. Research into the genetics underlying the condition has several values beyond just the Saddlebred breed as it may "serve as a model for investigating congenital skeletal deformities in horses and other species."[6] Other Lordosis behavior refers to the position that some mammalian females (including cats, mice, and rats) display when they are ready to mate ("in heat"). The term is also used to describe mounting behavior in mammalian males. In radiology, a lordotic view is an X-ray taken of a patient leaning backwards