This paper offers an examination of the representations of Sudanese

advertisement

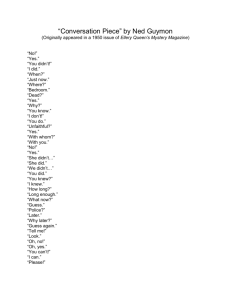

Mediatised Public Crisis and the racialisation of African youth in Australia Abstract In this paper I analyse how African populations living in Melbourne have been constituted as racially ‘other’ subjects through intensive mediatisation and politicisation of a small number of violent events. The events themselves offer little support for the thesis that African refugees are prone to violence as a consequence of racial and cultural attributes, yet this is precisely the message conveyed through media reporting. This presents serious challenges for Africans living in Australia, and for others who accept racialising discourses, as well as for social cohesion in Australia. The analysis will rely on print media reporting in Melbourne in 2007-2008 in order to demonstrate how the social fields of police work, journalism and politics interact to produce distinctive racialising effects. In late 2007, after two months of heavy reporting focused on groups of young men most often profiled as African or Sudanese, the Melbourne tabloid Herald-Sun published the following editorial: We are in the grip of a violence epidemic, fuelled by four persistent factors: alcohol, groups of young males, illegal weapons and, increasingly, cultural differences involving immigrant youths. (A stab in the darkness, 2007) This thesis is purportedly demonstrated foremost by three violent incidents. On Wednesday September 26 2007 Liep Gony, a 19-year-old student who came to Australia from Sudan in 1999, was bashed at a train station in the Melbourne suburb of Noble Park. He died 24 hours later from his injuries and two ‘white’ men were subsequently charged 1 with his murder. On the day before his funeral, another refugee from Sudan, Ajang Gor, was bashed in the suburb of Melton, and his family sent racist text messages on his stolen mobile phone. On November 29, in a third Melbourne suburb, police made violent arrests at a housing estate, describing the event as ‘a riot’ provoked by ‘African youths’. From late September to early December 2007, ‘African youth’ were consequently the object of intense media attention in Australia. Reporting took on an explicitly political dimension after the Minister for Immigration commented on Liep Gony’s murder that some groups ‘don’t seem to be settling and adjusting into the Australian life as quickly as we would hope’ (Topsfield & Rood, 2007). This ‘failure to integrate’ was given as justification for a cut in the number of humanitarian visas allocated to Africans from 70% to 30% (Topsfield, 2007, p. 2). The processes of racialisation which I identify here are shaped by previous episodes in which race came to offer an explanation of social relations and rights. The framing of the incidents resonates strongly with that established by the ‘Tampa Crisis’ of 2001, and ‘children overboard’ affair, in which the government used the plight of refugees attempting to reach Australia to play on xenophobic fears and win that year’s Federal election (Gale, 2004). It also resonates with anti-Muslim and anti-Arab/Lebanese sentiment in its focus on young men constituted as ‘ethnic crime gangs’ identified by appearance (AntiDiscrimination Board of New South Wales, 2003; Collins, 2000). This racism is felt widely within the targeted populations (Poynting & Noble, 2004), with the relationship between vilification and persecution most visible in the Cronulla Riots of 2005 (Poynting, 2006). Common to all of these episodes is the central role of the media in promoting racialised accounts. Racialisation is understood here as ‘the cultural or political processes or situations where race is involved as an explanation or a means of understanding’ (Murji & Solomos, 2005, p. 11). The media, in these instances, construct what has been termed a mediatised or mediated public crisis (Cottle, 2004, p. 2; McCallum, 2007, p. 1). 2 How then can we consider the relationship between a given set of events, their interpretation as having a racial quality, and the workings of the media? The work of politicians must also be considered if this set of relationships is to be analysed. While Fairclough (2000) uses the term mediatisation to describe how government seeks to use and manage the media, I am concerned here with the ways in which the media take up events as policy issues, even when they only weakly relate to a specific already-existing government policy – a practice theorised by Lingard and Rawolle (Lingard & Rawolle, 2004). By mediatisation, therefore, I refer to the process of symbolic transformation whereby any given event becomes a media event (Bourdieu, 1998). Bourdieu’s theorisation of social fields offers a useful approach for examining the movement of events across law-enforcement and judicial, journalistic and political domains. A ‘temporary social field’ (Rawolle, 2005) is constituted by the attention granted to violent events involving African refugees. The structure of this temporary social field is derived from cross-field positionality of a small group of mobile agents. In particular, members of the police force play a critical role in setting the dynamic of this temporary social field. Bourdieu’s analytical framework distinguishes a set of social fields, each of which operates autonomously according to somewhat distinctive principles of social value and participation. These fields call forth distinctive positional strategies from those agents competing for the symbolic or material stakes of each field (which Bourdieu terms capital). Social fields are organised within a wider field of social power, which provides the basis for the exchange of capital accumulated in various fields. Here I am concerned with the relationships of fields contributing to what Bourdieu has termed the ‘journalistic field’ (Bourdieu, 1998). Bourdieu (1998) suggests that the logic of the journalistic field tends to distort objects which come to its attention, and that the true objects of media attention are internally produced realities, developed according to the 3 structural properties of the field. These include the search for the novel, the rapid news cycle, the need for articulate spokespeople, and the desire for ratings (Bourdieu, 1998, pp. 21-23). All of these elements are determined by the particular susceptibility of the journalistic field to commercial imperatives emerging from the economic and political fields. In this sense, journalism is a ‘dominated field’ which ‘tends to reinforce the ‘commercial’ elements at the core of all fields to the detriment of the “pure”’ (Bourdieu, 1998, p. 70). The relationship of the political field to the journalistic field and to policy remains somewhat ambiguous in Bourdieu’s work. He writes that ‘in a certain way, the journalistic field is part of the political field on which it has such a powerful impact’ (1998, p. 76). The journalistic field threatens the autonomy of others by supporting actors from other fields who are ‘most inclined to yield to the seduction of “external” profits precisely because they are less rich in capital specific to the field’ (74). In order to analyse below the consequences of this movement across fields of heteronomous agents, I draw on the concept of ‘cross-field effects’ developed by Lingard and Rawolle (Lingard & Rawolle, 2004; Rawolle, 2005). These effects, which are the result of mediatisation, impact on policy, and micro-social relations through the production of a ‘temporary social field’, whose structures are ‘derived from the relationships between the fields of journalism and the fields of politics, derived from the social fact that they share common stakes’ (Rawolle, 2005, p. 712). Refugees in Australia The Australian government currently has a target of 13,000 new arrivals per year through its humanitarian program. In 2005/2006 grants to people from Africa comprised 55.65 per cent of this intake; grants to people from the Middle East and South West Asia comprised 33.98 per cent; and grants to people from the Asia/Pacific region comprised 9.88 per cent (Australian Government, 2007). 4 Refugees from Africa began forming an important part of Australia’s humanitarian entry program from the end of the 1990s, but still make up less than 1% of the population. This intake has been drawn from linguistically and ethnically diverse populations, primarily from the Horn of Africa, but also from countries in West Africa. As the largest number come from Sudan, ‘Sudanese’ is often used to cover all ‘Black’ refugees. As we shall see below, in media representations refugees from Africa are often presented as being members of a single community, with no ethnic or linguistic boundaries recognised and nation often standing for ‘race’. However Sudan, to take one example, counts over 600 ethnic groups and 400 languages (Levinson, 1998, p. 170). These groups have a complex history and encompass wide-ranging cultural and religious differences, as well as economic and social distinctions (Levinson, 1998, p. 170-172). The projection of ‘orientalist’ fantasies (Said, 1995) on a heterogeneous African population primarily on the basis of appearance is made possible by ignorance of such distinctions. The study The study consists of analysis of print media articles from Melbourne newspapers relating to the events outlined at the start of the paper. Articles from the Herald-Sun, The Australian (both News Limited) and The Age (Fairfax) appearing from September 26, 2007, when Gony was bashed, to December 3 2007, when attention subsided, have been included in the analysis. A total of 222 news and opinion articles published over the period were identified using the ‘Factiva’ data-base. I draw on the tools of critical discourse analysis. I will therefore discuss media portrayals in terms of ‘frames’, by which I mean the construction of narratives through the selection, ordering and manipulation of perspectives and experiences to produce a particular ideological meaning (Gamson, Croteau, Hoynes, & Sasson, 1992; Gitlin, 2003; Iyengar, 1991; Kendall, 2005; Norris, Just, & Kern, 2003). My ultimate objective is to 5 clarify the roles of various agents contributing to the ‘temporary social field’ constituted by media attention to African refugees in Melbourne. The role of the police The reliance of journalists on particular ‘beats’ on regular institutional sources, such as the police, as a matter of both efficiency and routine (Gans, 2004; Sigal, 1973), has a powerful structuring effect on media frames. The ‘local talk’ (McCallum, 2005) of police, although it may be expressed in particular ways in the presence of journalists, plays a powerful double role in constituting public opinion. It is transformed from the ‘localised’ public opinion grounded in discussion of experience and media consumption into mediated public opinion, often covertly, through the offices of journalists on crime beats. The same forces of police organisational culture which influence individual police officers are relayed far beyond their originating contexts by virtue of this symbiotic relationship. In this case, newspapers develop a commitment to racialising narratives of urban decay and violence presented by police, and then prioritise stories which appear to fit in to this narrative. Internationally, the role of the police in processes of racialisation has been well established since Stuart Hall’s seminal Policing the Crisis (1978). It is evident in the widespread and routine harassment and identity checks carried out on visible minorities by police (Chan & Mirchandani, 2002; Holdaway, 1996; Poynting, 2001), with institutional police racism in Australia brought to greatest focus in recent times through the inquiry into Aboriginal deaths in custody (Johnston, 1991). Police racism towards African refugees in Australia has also begun to be documented. An internal police report leaked to the press during the events analysed here made adverse findings in relation to complaints made by young African men of harassment, assault and racial abuse (Porter, 2007, p. 5). Recent research in Melbourne on refugee youth aged 12-20, (85% of whom were born in Africa) has also reported that 6 half of males and a fifth of females were stopped and questioned by police in the first two years of settlement (Refugee Health Research Centre, 2007). Comments from participants in the study reveal resentment of racial profiling: A police car pulls over and they’re like ‘are you guys a gang or something?’ ‘No we’re just friends, we’re walking’… Just a group of kids walking together doesn’t mean they’re a gang! (Ethiopian male 15 years old in (Refugee Health Research Centre, 2007, p. 2) As Police are given the first and greatest authority to name and define the crimes they are called to, it is unsurprising that it is their labels and descriptions which are taken up and remain affixed through subsequent reporting. At the outset of media attention instigated by the bashing of Liep Gony, reports focus on the story that ‘ethnic gang violence has erupted on suburban Melbourne streets’, with extensively quoted ‘local officers’, complaining that ‘they [the Sudanese] walk around in packs’(Kerbaj, 2007, p. 8). Police are backed up by anonymous ‘residents’ in the characterisation of Sudanese as having a ‘gang mentality’ resulting in ‘ugly clashes with other migrant groups’. The bashing of Gony is primarily newsworthy initially due to the incorrect assumption that it is a ‘savage gangrelated attack’. The implications of the labelling so freely used in this reporting, which point to the working hypothesis used by police in approaching any incidents involving ‘problem groups’, are discussed in the next section. Defining a problem group Definition of a racialised ‘problem group’ is achieved here most obviously through ‘overlexicalisation’ (Teo, 2000): the density of epithets relating to racial, age, collective and migration attributes (see Table 1 below). At least one descriptor from all four categories is 7 used in every article reviewed in relation to the ‘problem group’, in addition to the specification that it is ‘men’ who are the problem. Moral qualities more rarely appear as labels (column 6), but rather are conveyed through more elaborate means analysed further in the next section. Even when identification is suppressed in court proceedings, race may explicitly excluded, as in the case of a magistrate’s ruling that ‘I don't think his name should be mentioned, only that he is Sudanese and he comes from the Dandenong area’ (Roberts, Anderson, & Sikora, 2007, p. 4). While Africans may be residents of a given suburb, they are rarely described as locals. Geographically, the suburbs where migrants live are portrayed as besieged by outsiders and cut off from the city. They are ‘no-go zones’ (Mitchell, 2007, p. 25), ‘African, Asian and Polynesian strongholds’, ‘hotspots’ and ‘hotbeds’ for ‘youth violence and ethnic tensions’ (Lloyd-McDonald, 2007, p. 3). This identification lost territory and invasion is emphasised by references to an idyllic past time. A ‘75-year-old widow’, who is a ‘local’, laments that before the invasion, ‘the area used to be “lovely”’ (Crawford, 2007, p. 4). The descriptors in Table 1 all stand in for appearance in some way, as it is appearance which primarily forms the basis for profiling. This is recognised by those who are subjected to profiling: ``We are black and we stand out, so we are targets’, a ‘rake-thin Sudanese youth’ is quoted as observing (Franklin, 2007a). Note in the above extract that ‘race’ is by build by the reporter. African sources are constantly objectified and racialised through such references to build (‘skinny’ and ‘tall’) and demeanour (‘defiant’, ‘swaggering’). Farouque and Cook report of Noble Park that ‘their skin tone, height and clothing and a certain defiant attitude make these Sudanese-born youths stand out’ (Farouque & Cooke, 2007, p. 3). Height in particular is frequently evoked in relation to the Sudanese, with a man appearing in court unusually described as ‘the 188cm teenager’ (Roberts et al., 2007, p. 4). In the articles reviewed, height is never used to describe any other non-African individual or group referred to. 8 Commonly, the ‘over-lexicalised’ ‘problem group’ is counterposed with ‘locals’ or ‘residents’, who are implicitly white (Table 2). These ‘deracialised’ individuals tend to be identified only by profession and individual age. When reports emerged of arrests made in relation to the bashing of Liep Gony (associated with least 4 of the descriptors in Table 1 per article), those arrested are described first as ‘three people’ (Bashing arrests, 2007, p. 7). They are given exact ages (22, 19, 17), and reference is not made to their youth. They are ‘two men and a woman’, not youths or teenagers or migrants or of any particular background (Bashing arrests, 2007, p. 7). On the following day, it is revealed that ‘Mr Gony’s alleged attackers were not African’, and the suspects aged over 18 are named (Farouque, Petrie, & Miletic, 2007, p. 2). By October 6, the ‘race’ of the attackers is finally made explicit: ‘three white people have been charged over the incident’ (Farouque & Cooke, 2007, p. 3). Even though deracialised figures by definition are bereft of racial attributes, here they are added for clarification that they are not part of the ‘problem group’. Police are defined more simply yet by rank. Only once is a police officer racially profiled; when the ‘irony’ of a ‘Sri Lankan-born detective’ asking ‘raucous Sudanese’ to disperse is pointed out (Bolt, 2007b). The irony lies, presumably, in the fact that this officer is not white, and so does not fit the deracialised profile of the ‘normal’ police officer. 9 Table 1: Common descriptors for ‘African refugees’* Racial attributes Collective Age Migration locality Moral attributes attributes attributes African a mob youth(s) refugees ‘North African’ packs kids immigrants lawless Of African descent’ a gang children migrants thugs Black gangs under-age Sudanese a group teenagers ‘Sudanese-born’ community teens qualities residents delinquent offenders juvenile *Articles appearing in Melbourne September 26 – December 3 2007. Table 2: Common descriptors for other lay sources/ ‘deracialised’ groups referred to* Racial attributes Collective Age attributes attributes White ‘the community’ Caucasian ‘the people’ Non-African Migration Locality attributes [age]-year-old Moral qualities ‘long-term locals Australians’ residents locally-born ‘long-time residents’ home-grown neighbours ‘local businesses’ *articles appearing in Melbourne September 26 – December 3 2007. Behind the labelling often lies the thesis of an African ‘culture of violence’. Assistant Commissioner Paul Evans claim that investigators are ‘dealing with refugees who had come from a culture of boy soldiers and social violence’(Evans, 2007b, p. 3). Elsewhere the commissioner explains `this is a cultural thing. A lot of these people are brought up as warriors in their own country' (Mitchell, 2007, p. 25). Police are reportedly fearful ‘of the 10 emergence of militant street gangs of young African refugees who have served in militia groups in their war-ravaged homelands’ (Kerbaj, 2007, p. 8). This perspective is relayed by columnists. Andrew Bolt in the Herald-Sun claims that ‘Sudanese men come from a warlike culture and arc up more quickly than most when in a group’ (2007b, p. 34), while Neil Mitchell in the same newspaper suggests an animal quality with his evocation of ‘groups of young men hunting in packs’ (2007, p. 25). Witnesses from this ‘culture of violence’ lack credibility in disputing police versions. Their accounts are frequently portrayed as ‘claims’ and police accounts as ‘descriptions’. Countering the police description of a riot of 100 ‘African youths, a reporter cites an African source thus: ‘”It was 15 people”, swore a black man whose cheeks bore scars of tribal initiation’ (Franklin, 2007b, p. 5). Further in the same article, the lack of credibility of Africans is further demonstrated by failure to speak in English: Two women, short, stout and swathed in multi-coloured robes, stepped before one of the TV crews and yelled a blue streak, fists pumping and faces contorted with fury. Trouble was, there wasn’t a word of it in English and while they generated some first rate footage, no one black, white or blue was any the wiser. That was par for the course. Yesterday in Flemington nothing made any sense at all (Franklin, 2007b:5). The saliency of race is emphasised through the anonymity of these incomprehensible individuals, who are legible only through the peculiarities of their physical appearance. Dangerous youth 11 The framing of the ‘problem group’ as ‘youth gangs’ fits in with wider moral panics about juvenile delinquency (pertaining to crime, sexuality and drug use) and the decline of traditional standards and parental authority. The good-migrants/bad-migrants opposition identified in earlier research (van Dijk, 1992, pp. 131-132), here emerges primarily as a generational one. The first generation, with traditional culture intact, is ‘good’, while the youth run amok. A police source explains that ‘the elders in the community are very good people but they have trouble controlling some of the young kids’ (Farouque & Cooke, 2007, p. 3). The officer goes on to clarify that the problem is not with black African culture, as many others claim, but only with corrupting black American culture: ‘They're not mimicking the traditional Sudanese culture, they're mimicking the African-American culture, and it does cause problems down there.’ (Farouque & Cooke, 2007, p. 3). Similarly, a Herald-Sun editorial reports concern from ‘Sudanese community leaders’ ‘over a breakdown in traditional family discipline when youths leave home at 16 and embrace American rap culture’ (A problem with settling, 2007, p. 24). Contestations of police accounts and the theory of racial conflict The construction of the racialised ‘problem group’ outlined by police, relayed by the media and played with by politicians, is met with resistance from the outset. By the 11th of October, in the midst of Liep Gony’s funeral and the explicitly racist bashing of Ajang Gor, reports were full of community demands for an apology from Minister Andrews. An editorial in The Age asked of the Government’s decision to halt the intake of refugees from Africa ‘are its reasons justifiable or are they designed, in the face of an election, to arouse a predictably base reaction from those sensitive to immigration on racial grounds?’ (No Africans allowed, 2007, p. 14). 12 Criticisms of police also became sharper after reports of a ‘riot’ between ‘north African residents of Flemington’ and police were challenged. Police accounts were quickly disputed by other witnesses, and significantly given the doubt accorded ‘African’ witnesses’ accounts, they were contradicted by a ‘white’ restaurant owner (Anderson & Dowsley, 2007, p. 5). Scrutiny was boosted by the advocacy of a local Community Legal Centre, whose lawyer named police prejudice as ‘the problem’ and complained that ‘the youth are heavily targeted and under constant police surveillance’ (Farouque, 2007, p. 6). The treatment of events involving African refugees as either demonstrating the existence of racial tensions, or as eliciting a racist response, varies across media outlets. An examination of just those articles discussing Liep Gony’s case demonstrates this (Figure 1). Figure 1: Frequency of Articles Reporting on Liep Gony by Quarter 40 35 30 Australian 25 The Age 20 Herald-Sun 15 Total 10 5 0 Sep- Oct- Nov- Dec- Jan- Feb- Mar- Apr- May- Jun- Jul- Aug- Sep07 07 07 07 08 08 08 08 08 08 08 08 08 Of 59 articles reporting on Liep Gony, we can see from Figure 1 that the tabloid Herald-Sun appears to pay greatest attention to Liep Gony’s case, followed by the broadsheet Age newspaper. However mention of Gony is more evenly spread between the different publications in the aftermath of the initial events, and the pattern of reporting suggests that all three newspapers follow a logic of journalistic value common to the field in determining how to report on the case. There are important qualitative differences in 13 reporting which are hidden by the frequency of coverage, and which are revealing of how political agendas are played out in the media. Table 3 presents in the first row those articles which focus on Liep’s case as an illustration of racial conflict. presented either by police, politicians, or columnists. This thesis is The two more conservative publications, which are both part of the Murdoch stable, are twice as likely as The Age to focus on racial conflict in reporting. Liep’s bashing continues to be used as a demonstration of minority ethnic violence into 2008. Violence is described as ‘ethnic-related’ and ‘race-based’ (Anderson, 2007c). The Age header for its reporting on the day of Liep Gony’s funeral reads ‘Race Tension’. Commentator Neil Mitchell concludes that ‘It is a significant and ugly step to ban refugees on race, but that is what is being done because the problems are racially based’ (2007, p. 25). The Age, by unlike other outlets, offers no overt editorial support for this perspective, and produces reports of the racial conflict thesis primarily in presenting the comments of Kevin Andrews. Instead, The Age offers some editorial support for accusations of racism in the treatment of the case, and this is reflected in the relatively higher proportion of articles which focus on accusations of racism. Common in The Age and the Australian are articles which give similar weight to racial conflict perspectives and to accusations of racism (these are entered under both categories in the table). The Herald-Sun newspaper is almost silent on accusations of racism, relative to the total number of articles mentioning Gony. It must be concluded from this analysis that the racial dimension of this case was what most interested the journalistic field. Three quarters of all reports make deliberate mention of racial and ethnic tension. Some court reporting, and reports of the arrest of white suspects, are virtually the only exception to this rule. 14 Table 3: Predominant themes in articles reporting on Liep Gony The HeraldAustralian Age Sun Total Racial conflict thesis (n) 7 8 16 31 % 64 36 62 53 Accusations of racism (n) 4 10 4 18 %* 36 45 15 31 Racial dimension emphasised 8 16 20 44 % 73 73 77 75 Total articles (n) 11 22 26 59 * These categories are not mutually exclusive, so totals may exceed 100% Relationships between fields I have argued above that reporting on violence involving African refugees has been most influenced, at least initially, by police accounts. Here I wish to sketch further how police, and other agents, are connected to the process of mediatisation. In the field of law enforcement, police are concerned with the practical difficulties confronting them in their daily duties, and in providing explanations of the phenomena they encounter. They are also concerned to provide justification for the value of their work and to define successful policing in terms which allow them to operate effectively. The values and interpretations emphasised vary depending on the position in police hierarchy of individual police officers, and based on the cultures of particular police stations. This is most obvious in the distinctions drawn between the official comments provided by force command and ‘on-the-street police’ (Mitchell, 2007, p. 25) whose often anonymous claims hold greater authority. Police on the ground are characterised as not being ‘racist rednecks’ but ‘people in the middle’, dealing with a reality of violence (Mitchell, 2007, p. 25). Low-ranking police are able to reposition themselves to gain greater power over their work, and greater recognition of the challenges they face, by participating in media production as sources for journalists. Journalists, for their part, tend to favour these sources because they can offer ‘eye-witness accounts’, which are most highly valued in 15 the journalistic field. Journalists, like low-ranking officers, are suspicious of the spin produced by senior officers who are consciously seeking to shape media reporting. Cooke, siding with ‘police on the ground’ writes in The Age: The reality for those at the coalface, however, might be slightly different, and it is believed some police have expressed frustration at having to parrot the line that there is ‘no problem’ with African youth. (Cooke, 2007d, p. 4) Here, ‘police on the ground’ act as the ‘moral license’ (Poynting, 2006, p. 88) for politicians to enter the fray. For them, participation in the journalistic field is of even greater interest in terms of the rewards it can bring them in their own, political field. The Immigration Minister, for example, relied on concerns expressed to him by ‘police on the ground’ about ‘a serious Sudanese gang problem’ to defend his view that Africans are ‘not integrating’ (Kerbaj, 20007, p. 3). This in turn supports greater freedom of manoeuvre for Despite having ‘white’ suspects, arrested interstate, in hand, police report to police. journalists that they are planning wider retaliation in the form of ‘a hard response to the packs of youths who roamed the area near the crime scene’, including the use of police dogs (Evans, 2007a, p. 3). According to Anderson, they have ‘vowed to clamp down on gang activity in the area’ in order to defer violence ‘within the community of youth North Africans and Pacific islanders (Anderson, 2007c, p. 15). The cast of participants extends well beyond politicians and police, but additional participants are forced to contribute on the terms established earlier in the mediatising process. After Minister Kevin Andrews made his announcement that the quota of refugee places allocated to Africa had been cut because of their difficulties in ‘settling in’, reporting turned increasingly to the broader question of integration, drawing on quotes from 16 politicians, public figures, and community representatives. The framing of integration problems is accepted in the Labor opposition’s response, with its spokesman Tony Burke, suggesting that individual capacity to integrate rather than collective capacity to integrate should be considered in visa applications (Packham, Whinnett, & Anderson, 2007, p. 1). Migrants are therefore obliged to offer reassurances of their ability to integrate. The front page of The Age on October 4 read ‘African Refugees: While Kevin Andrews doubts their ability to integrate, happy migrants tell it differently’, over a colour photo of Nywl Madut, quoted as saying ‘I have been here five years now, and I don’t think of myself as African’. Those identified as ‘African’ or ‘Sudanese’ must make the collective defence ‘we are not violent’ (Crawford, 2007; Jean, 2007, p. 5). Community leader Martin Johnson even offers apologies for the ‘young Sudanese’, which is cast as a collective racial responsibility: ‘we are sorry for what our kids have been doing and sorry for what has been happening to the community in Australia’ (Mitchell, 2007, p. 25). Non-migrant ‘locals’ in their contributions on the integration question appear to represent Australia as a fantasy paradise when they are called upon to offer opinions of refugees. A Mrs Hargreaves is quoted as saying ``I don't mind that they're here, as long as they learn to live like Australians’ (Crawford, 2007, p. 5) while a bottle shop owner complains that ‘they choose not to adapt to the Australian way of life and more annoying they do not like to abide by our laws’ (Mitchell, 2007, p. 25). As Bourdieu (1988) has suggested, the journalistic field tends to demand articulate representatives of the groups it seeks to define, and which it influences. But this tendency also extends to the police responses to what they perceive directly, through their experiences, and indirectly, through media reporting, as an issue of conflict between two distinctive cultural and social entities. Police ‘operation Square’ has been set up to reduce crime through discussions between police delegates and ‘African leaders’ (Anderson, 2007a), casting misunderstanding and miscommunication as the source of 17 problems,. Through meetings with ‘leaders’, responsibility for social control may be delegated, at least symbolically, to individuals who are part of the troubled racial entity. Police may, in this framing, legitimately lay the blame on the delegates of the community for its failures, and do not hesitate to criticise the failure of community leaders to ‘address the problems in a “small group”’ (Farouque, 2007, p. 6). Such a criticism is predicated on the existence of a unified racial entity and which may be addressed through delegated individuals and establishes this entity as bearing wide-ranging collective responsibility for particular incidents and even for police suspicions. Media and police appear to mutually reinforce their perspective that this is the case. Conclusion Despite the incidents triggering attention being primarily attacks on African refugees, including by police, the ‘problem’ is cast with the victims. We find two main framings of ‘the problem’. The most immediate of these references ethnic-youth-gang-conflict. This conflict is held to be generated by visible minority groups, whose proclivities justify assuming that all events in which they are involved may be explained by their racial attributes. A wider framing of ‘the problem encompasses as its causes the difficulties of integration. Racialisation of African refugees in the Australian media appears to find its proximate source in the activation of race as an explanatory category amongst police, giving license to a xenophobic minority. This activation draws on the history of racism in Australia, on wider colonial narratives about primitive Africa, on the perennial discourse of dangerous youth, and even on fears about American cultural imperialism (in the form of Black ‘gang culture’). As with Indigenous Australians, the dominant frame is one of underlying societal risk (McCallum, 2007). 18 The organisation of news production creates here a particular lens which tends squash events into similar kinds of story. Wider social dynamics of racism prefigure these framings and the dominant perspectives of police are the prime condition of existing frames. The attitudes and perspectives of politicians, though not shaped by the same experiences and with a greater eye to the reception and resonance of their contributions, are also influential in this process. Awareness of process of racialisation amongst journalists and sources who contribute to this cycle does not appear to be able to break the pattern and suggests that the power of dominant police perspectives is relatively undiminished by subsequent anti-racist impulses in reporting. References A problem with settling. (2007, October 4). Editorial. Herald-Sun, p. 24. A stab in the darkness. (2007, December 1). Editorial. Herald-Sun, p. 86. Anderson, P. (2007a, November 29). Atrocious, appalling crimes. Herald-Sun, p. 12. Anderson, P. (2007b, October 14). Police battle to hold gang wars. Herald-Sun, p. 11. Anderson, P. (2007c, October 1). SA cops arrest 4 on bash death. Herald-Sun, p. 15. Anderson, P., & Dowsley, A. (2007, November 30). Police 'feared for safety' as they were surrounded. Herald-Sun, p. 5. Anti-Discrimination Board of New South Wales. (2003). Race for the Headlines: Racism and Media Discourse. Sydney: Anti-Discrimination Board. Australian Government. (2007). Fact Sheet 60. Australia's refugee and humanitarian programme. Canberra: National Communications Branch, Department of Immigration and Citizenship. Bagdikian, B. H. (2000). The media monopoly (6th ed.). Boston, Mass.: Beacon Press. Barker, M. (1981). The new racism : conservatives and the ideology of the tribe. London: Junction Books. Bashing arrests. (2007, October 1). Bashing arrests. Australian, p. 7. Bolt, A. (2007a, October 5). Big hearted. Herald-Sun, p. 28. Bolt, A. (2007b, October 12). It's time we got a grip. Herald-Sun, p. 34. Bourdieu, P. (1998) On television and journalism. London, Pluto Press. Buttler, M. (2007, October 11). African teen bashed. Herald-Sun, p. 4. Castles, S. (2003). Towards a sociology of forced migration and social transformation. Sociology, 37(1), 13-34. Chan, W., & Mirchandani, K. (2002). Crimes of colour : racialization and the criminal justice system in Canada. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press. Cohen, S. (1972). Folk devils and moral panics: the creation of the Mods and Rockers. London,: MacGibbon and Kee. Collins, J. (2000). Kebabs, kids, cops and crime : youth ethnicity and crime. Annandale, N.S.W.: Pluto Press. 19 Cooke, D. (2007, October 4). Sudanese no more prone to crime than other groups in the community: Nixon. The Age. Cottle, S. (2004). The racist murder of Stephen Lawrence : media performance and public transformation. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. Crawford, C. (2007, October 4). Widow feels trapped. Herald-Sun, p. 5. Critcher, C. (2003). Moral panics and the media. Philadelphia: Open University Press. De Lepervanche, M. M. (1988). Racism and sexism in Australian national life. In G. Bottomley & M. M. De Lepervanche (Eds.), The Cultural construction of race (pp. 139 p.). Annandale, N.S.W.: Sydney Association for Studies in Society and Culture. Deuze, M. (2007). Media work. Cambridge, UK ; Malden, MA: Polity. Evans, C. (2007a, October 1). Three in custody over bashing death. The Age, p. 3. Evans, C. (2007b, October 1). Two charged over teen bashing death. The Age, p. 3. Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical discourse analysis : the critical study of language. London ; New York: Longman. Fairclough, N. (2001). Language and power (2nd ed.). Harlow, Eng. ; New York: Longman. Farouque, F. (2007, November 30). Accord threatened as refugees struggle with police. The Age, p. 6. Farouque, F., & Cooke, D. (2007, October 6). Ganging up on Africans The Age, p. 1. Farouque, F., Petrie, A., & Miletic, D. (2007, October 2). Minister speaks on Africans. The Age, p. 2. Franklin, R. (2007a, October 4). This was no place to die Light at tunnel's end snuffed out. Herald-Sun, p. 31. Franklin, R. (2007b, November 30). Truth is out there somewhere. Herald-Sun, p. 5. Gale, P. (2004). The refugee crisis and fear: populist politics and media discourse. Journal of Sociology, 40(4), 321-340. Gamson, W. A., Croteau, D., Hoynes, W., & Sasson, T. (1992). Media images and the social construction of reality. Annual Review of Sociology, 18, 372-393. Gans, H. J. (2004). Deciding what's news : a study of CBS evening news, NBC nightly news, Newsweek, and Time / Herbert J. Gans. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press. Giroux, H. A. (2006). Beyond the spectacle of terrorism : global uncertainty and the challenge of the new media. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers. Gitlin, T. (2003). Media unlimited : how the torrent of images and sounds overwhelms our lives (1st Owl Books ed.). New York: H. Holt. Grattan, M. (2007, October 10). Sudanese teenager bashed. The Age, p. 7. Hage, G. (1998). White nation : fantasies of white supremacy in a multicultural society. Sydney: Pluto Press. Hall, S. (1978). Policing the crisis : mugging, the state, and law and order. London: Macmillan. Holdaway, S. (1996). The racialisation of British policing. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire New York: Macmillan Press ; St. Martin's Press. Iyengar, S. (1991). Is anyone responsible? : how television frames political issues. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Jean, P. (2007, October 4). Now we're poll victims. Herald-Sun, p. 5. Johnston, E. (1991). National Report: Royal Commission into Aboriginal deaths in custody: Volume 5. Canberra. Karvelas, P. (2007, October 8). Sudan call shows `incompetence' The Australian, p. 6. Kendall, D. E. (2005). Framing class : media representations of wealth and poverty in America. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. 20 Kerbaj, R. (2007, September 28). Sudanese migrants `fighting islanders'. The Australian, p. 8. Kerbaj, R. (20007, October 4). Police in denial on gangs: Andrews. Australian, p. 3. Levinson, D. (1998). Ethnic groups worldwide : a ready reference handbook. Phoenix, Ariz.: Oryx Press. Lingard, B., & Rawolle, S. (2004) Mediatizing educational policy: the journalistic field, science policy, and crossfield effects, Journal of Education Policy, 19(3), 361-380. Lloyd-McDonald, H. (2007, September 29). Death finds a way: Liep Gony's family fled war in Sudan. Herald-Sun, p. 1. Lunn, S., & Davis, M. (2007, October 12). Andrews denies fanning violence. The Australian, p. 9. McCallum, K. (2007). Indigenous Violence as a 'Mediated Public Crisis'. Paper presented at the Australian and New Zealand Communication Association Conference. McCallum, K. (2005). Local Talk as a Grounded Method: Elaborating Media and Public Opinion on Indigenous Issues. International Journal of the Humanities, 3(5), 113122. Mitchell, N. (2007, October 4). Above the law in the suburbs Herald-Sun, p. 25. Mitchell, N. (2008, 24 January). What's wrong with our town? Herald-Sun, p. 31. Multicultural undercurrents. (2007, September 28). Editorial. Herald-Sun, p. 30. Murji, K., & Solomos, J. (2005). Racialization : studies in theory and practice. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press. No Africans allowed. (2007, October 4). Editorial. The Age, p. 14. Norris, P., Just, M. R., & Kern, M. (2003). Framing terrorism : the news media, the government, and the public. New York: Routledge. Oakes, D., & Cooke, D. (2007, October 11). Community's anger spills over. The Age, pp. 1, 8. Otunnu, O. (2002). Population displacements: causes and consequences. Refugee, 21(1), 2-5. Packham, B., Whinnett, E., & Anderson, P. (2007, October 4). RACE STORM PM digs in over Africans. Herald-Sun, p. 1. Porter, L. (2007, September 30). Police accused of race attacks on Africans. Sunday Age, p. 5. Poynting, S. (2001). Appearances and 'ethnic crime' Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 13(1), 110-113. Poynting, S. (2006). What caused the Cronulla riot? Race and Class, 48(1), 85-92. Poynting, S., & Noble, G. (2004). Living with Racism: the experience and reporting by Arab and Muslim Australians of discrimination, abuse and violence since 11 September 2001. Sydney: Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission. Rawolle, S. (2005) Cross-field effects and temporary social fields: a case study of the mediatization of recent Australian knowledge economy policies, Journal of Education Policy, 20(6), 705-724. Refugee Health Research Centre. (2007). Promoting Partnerships with Police (No. Broadsheet #2). Melbourne: Refugee Health Research Centre. Roberts, B., Anderson, P., & Sikora, N. T. (2007, October 12). Detective shaken by violent attack Herald-Sun, p. 4. Said, E. (1995). Orientalism. New York: Penguin. 21 Sigal, L. V. (1973). Reporters and officials: the organization and politics of newsmaking. Lexington, Mass.,: D. C. Heath. Small, S. (1994). Racialised barriers : the Black experience in the United States and England in the 1980's. London ; New York: Routledge. Swartz, B. (2007, Decembe 2). Racist leaflet fuels tensions. The Age, p. 8. Teo, P. (2000). Racism in the news: a critical discourse analysis of news reporting in two Australian newspapers. Discourse & Society, 11(1), 7-49. Tilbury, F. (2004). They're intelligent and very placid people and it's unavoidable that they become your friends": Media reporting of 'supportive' talk regarding asylum seekers. Paper presented at the Revisioning Institutions: Change in the 21st Century TASA 2004 Conference. Topsfield, J. (2007, October 2). Behind the scenes on Sudanese refugees. The Age, p. 2. Topsfield, J., & Rood, D. (2007, October 4). Coalition accused of race politics. The Age, pp. 1, 4. van Dijk, T. A. (1992). Discourse and the denial of racism. Discourse & Society, 3, 87-118. van Dijk, T. A. (1993). Elite discourses and racism. London: Sage. van Dijk, T. A. (1997). Political discourse and racism: Describing others in Western parliaments. In S. H. Riggins (Ed.), The language and politics of exclusion: Others in discourse (pp. 31-64). London: Sage. 22