Britská literatura

advertisement

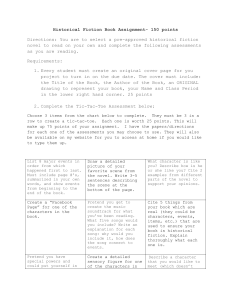

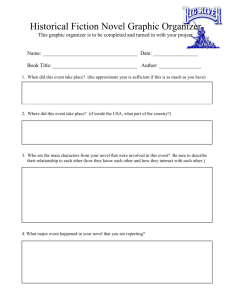

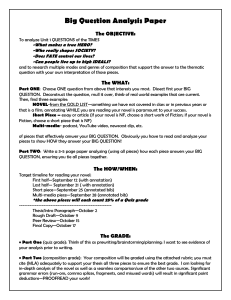

(15) Joseph Conrad T h e 2 0 th C e n t u r y [See Topic 13] T h e 2 0 th C e n t u r y F i c t i o n ( I ) H i g h M o d e r n i s m ( 1 9 2 0 s ) > a celebration of personal and textual inwardness: - the problems of lit. idea and practice became matters of intense debate as never before - the confidence in the great old certainties/old Grand Narratives shattered > seeking new alternatives to the old belief systems - incl. the later Henry James, J. Conrad, J. Joyce, D(avid) H(erbert) Lawrence, and Virginia Woolf Reality: - aim of fiction = to reproduce what appears to be the nature of the real - V. Woolf’s Modern Fiction (1919) = against the ‘materialism’ of the Edwardian heirs of Victorian confidence, i.e. Arnold Bennett, H(erbert) G(eorge) Wells, and John Galsworthy - reality existed only as it was perceived > a new impressionistic, flawed, even utterly unreliable narration presented by a not-to-be-relied-on narrator, ‘reflector’ (H. James): J. Conrad’s Marlow of Heart of Darkness and of his oth. fiction x the 19th c. authoritative narrating voice - => reality and its truth had gone inward: ‘Look within,’ V. Woolf urged the novelist Concern: - rejected materialist externality x but: the worldly subject, politics, and moral questions never completely omitted: (a) perplexities of the London and Dublin urban life: V. Woolf and J. Joyce (b) industrialism and provincial life: D. H. Lawrence (c) social subject and satire: George Orwell and Graham Greene ( the condition humaine in C. Dickens; and A. Bennett, H. G. Wells, and J. Galsworthy) - modern myth making: (+) J. Joyce’s Ulysses with Bloom mythicised as a modern Ulysses and his life’s odyssey paralleling episodes from Homer’s Odyssey; the old ‘narrative method’ replaced by a new ‘mythical method’, finding ‘a continuous parallel btw contemporaneity and antiquity’ (T. S. Eliot) x (−) D. H. Lawrence’s Aaron’s Rod with its fascist sympathies; and his The Plumed Serpent with the revived Aztec blood-cult - the metafictional novel = conc. with writers, artists, and surrogates for artists: V. Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway with her party = one of the ‘unpublished works of women’ Character: - < infl. by Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic movement = the reality of persons narrated as the life of mind in all its dimensions, i.e. consciousness, subconsciousness, unconsciousness, id, libido, etc. - stream of consciousness = the main modernist access to ‘character’: V. Woolf’s preocc. with ‘an ordinary mind on an ordinary day’ - free indirect style = entering the characters’ mind to speak as if on their behalf - existential loneliness = characters doomed to make their way through life’s labyrinths without much confidence in the knowable solidity of the world: J. Conrad’s Lord Jim, J. Joyce’s Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus, and V. Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway > confidence leaks away from the novel itself: V. Woolf’s Jacob remains stubbornly unknowable to his closest ones, above all to his novelist - => tricky, scattered, fragmentary narratives Presentation: - old conclusive tendency of plots ( detective story) x new open endings: the unending vista of the last paragraph of D. H. Lawrence’s Sons and Lovers, the circularity of J. Joyce’s Finnegans Wake with the last sentence hooking back to be completed in the novel’s 1st word, & oth. - linguistic self-consciousness: G. Orwell’s Newspeak in 1984, the culmination of his politically motivated engagement with E, and J. Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, the greatest example of linguisticity rampant as such and a monumental dead end ( I I ) S o c i a l R e a l i s m ( 1 9 3 0 s ) > a reaction against modernism: - < the impact of the Sp. Civil War and WW II > a return to registering the social scene > WW II inspired fiction: G. Greene’s The Ministry of Fear, Evelyn Waugh’s Sword of Honour trilogy, & oth. ( I I I ) P o s t m o d e r n i s t P l u r a l i s m ( 1 9 4 0 s + ) > a variety of realisms: - various realisms incl. urban, proletarian, regional (esp. Scott. and Ir.), provincial E, immigrant, postcolonial, feminist, gay, etc. Politics and Religion in the Post -WW II Novel: - > the new Welfare State atmosphere of the 1950s: John Wain’s Hurry on Down, a graduating scholarship-boy’s protest against the educational poshocracy - > the young demobilised officer class: Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim - a sense of posteriority (i.e. post-war flatness and post-imperial diminution of power and infl.) + a sense of the Grand Narratives now really losing their force > questioning for new moral bases - > William Golding’s post-Christian moral fables (The Lord of the Flies) and Iris Murdoch’s moral philos. (Under the Net) + their Roman Cath. contemporaries incl. G. Greene, Muriel Spark, and E. Waugh Stagnation of Fiction: - the late-c. E novel far too obsessed with the past > the postmodernists seemed condemned to simply parroting old stuff - obsession with Ger. and the ghosts of the Hitlerzeit: Martin Amis, Ian McEwan, & oth. - nostalgia for old imperial days: Lawrence Durrell (Alexandrian Quartet) x the earlier accusations for Br. overseas behaviour: J. Conrad, E. M. Forster (A Passage to India), & oth. - grief over the post-imperial decline of the once-grand centre of London: the later K. Amis, Doris Lessing, I. McEwan, and M. Amis (London Fields, The Information) New Trends in the 1970s – 80s Fiction: - new energetic end-of-c. writers from margins: (a) women writers: Beryl Bainbridge, dark historiciser of M as well as F plights; Angela Carter, feminist neo-mythographer, reviser of fairy tales, and rewriter of de Sade; & oth. (b) regional writers, esp. Ir./Scott. (c) genre writers (i.e. writers pushing their way into the mainstream from the generic edge, esp. sci-fi): Martin Amis (d) M-gay writers: Alan Hollinghurst, the pioneer of the openly M-homosexual novel (e) post-colonial writers: (a) old Commonwealth novelists residing in Br.: V. S. Naipaul, D. Lessing, & oth. + (b) overseas writers of Commonwealth orig.: Kazuo Ishiguru; Salman Rushdie, the Ind.-born importer of South Am. and Ger. (Gunther Grass-type) magic realism, a satirist of Ind./Pakistani/Br. life (The Satanic Verses); & oth. End-of-Century Condition of Fiction: - the end-of-c. (and end-of-millennium) Br. fiction desperately attempts to ward off the Br. novel’s contemporary sterility - => efforts important in their way x but: telling overdone: A. Carter’s sadomasochistic F heorics, M. Amis’s stylistic and formal extremes (the backward narration of his Holocaust novel Time’s Arrow), & oth. Joseph Conrad (1857 – 1924) Life: - b. in Poland (then under Rus. rule), son of a Polish patriot suffering exile in Rus. for his Polish nationalist activities - a merchant seaman: travelled the Pacific, esp. the East & West Indies, etc. - met and befriended J. Galsworthy on a South Sea voyage - a naturalised Br. subject > a sense of betrayal, guilt and dislocation in his work - with the success of his 1st novel Almayer’s Folly (1895) settled in London as a writer Work: - started learning E when 21 x but: became a master of E prose pop. for the romantic descriptions of exotic eastern landscapes x but: underlying serious themes (a) sea stories: employs the sea and the circumstances of life on shipboard or in remote settlements as a background for exploring moral ambiguities in human experience: tests the codes we live by in moments of crisis to reveal their inadequacy or our own - his sea-stories at least find some kind of resolution, though a singularly fragile one - (b) later more obviously political fiction - as much a pessimist as Hardy x but: projects it in subtler ways - conc.: the effects of Eur. imperialism in the Pacific, the East Indies, South Am., and Af. - colonisers = uncomprehending, intolerant, and exploitative - power = corrupting and open to abuse colonialism both brutal and brutalising The Nigger of the “Narcissus” (1897): - the eponymous character = a dying black seaman, corrupts the morale of a ship’s crew by producing sympathy - symbolically: the necessity and at the same time the dangers of human contact An Outpost of Progress (1898): - the eponymous ‘progress’ = an obvious misnomer - a nwsp from ‘home’ brightly discusses ‘Our Colonial Expansion’ in terms of ‘the rights and duties of civilisation to the dark places of the earth’ x but: the ‘darkness’ corrupts both internally and externally - > further develops the idea in his Heart of Darkness (1899) Heart of Darkness (1899): - < his own experience in a steamboat going up the Congo River in nightmarish circumstances - imperialism begins as a variety of brutish idealism, redeemed by the idea only x but: proves to lack such an idea as the narrative develops Lord Jim (1900): - conc.: a gross failure of duty on the part of a romantic and idealistic young sailor - the eponymous character = a successful colonial agent, earns himself the tile of Lord from his grateful subjects x but: marred by the lasting memory of the corruption of his predecessor - an intermediate narrator, a series of different POV suggest the complexity of experience and the difficulty of judging human actions Typhoon (1902): - = a sea novel Nostromo (1904): - = his masterpiece, a political novel - set in an unstable South Am. rep. in a tottering social order - conc.: the corrupting effects of politics and ‘material interests’ on personal relationships corruption both imported and exportable The Secret Agent (1906): - = a political novel, veers simultaneously twd farce and tragedy - set in a murky, seedy, untidy London - the eponymous character = Verlock, an agent provocateur in the employ of a ‘foreign’ (= almost certainly Rus.) embassy, required to blow up the Greenwich Meridian - < looks back to C. Dickens (esp. his policemen) - > the modern sense of alienation, disquiet, and dislocation; and the fragmented, reiterated phrases of the concl. anticipate the Modernists Under Western Eyes (1911): - = a political novel of Dostoyevskian power [Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821 – 81), author of Crime and Punishment (1866), The Idiot (1868), The Brothers Karamazov (1880), & oth.] - conc.: the dangerous instabilities of society under the Rus. autocracy the protagonist = Razumov (= ‘son of reason’), a Rus. student and government spy, gets involuntary involved with antigovernment violence in the tsarist Rus. and betrays a revolutionary fellow-student to the Tsar’s police - consequentially becomes a double exile in Switzerland, pretends to be a revolutionary among revolutionaries, to be the opposite of what he is - the narrator = an elderly E teacher of languages in Geneva, draws on his experience of R. and on his diary, observes all with foreign ‘western’ eyes, and only partially grasps R.’s pressing need for confession and expiation The Secret Sharer (1912): - set in the Gulf of Siam as felt by a young sea captain on his 1st command - in a small hierarchical society of the ship an individual decision and responsibility take on the moral force of paramount virtue - opening: the ‘great security of the sea as compared with the unrest of the land’ and the shipboard life present ‘no disquieting problems’ x but: becomes ironical as the narrative develops - conc.: the difficulty of true communion, communion as forced unexpectedly on us, and the recognition of our opposite as our true self - symbolically: the paradoxes of identity and sympathy The Shadow-Line (1917)