Business Cycle

advertisement

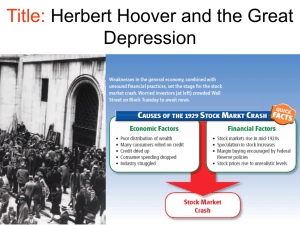

Business Cycle I BUSINESS CYCLE 1 Modern economies have alternated between periods of boom and bust. These are times of economic expansion and prosperity followed by economic downturns. Such periods of economic expansion followed by a contraction are called business cycles. During periods of expansion, employment remains high and prices remain stable or rise. 2 In a downturn, or recession, unemployment will rise, companies may be forced out of business, and prices tend to fall. Such economic cycles must not be confused with business fluctuations. A fluctuation of supply and demand, or of prices, may occur in a specific segment of the economy (or in several segments) without severely damaging the whole economy. In a business cycle the whole economy is affected simultaneously, in both its upswing and its downturn. Some geographic areas of a country may be more affected than others, depending on the types of local industries or agriculture. 3 A business cycle usually takes several years to complete itself. When the economy as a whole is slowing down, a recession is under way. (A severe and extended recession is called a depression.) In the United States between 1948 and 1992, there were nine recessions. They reached their lowest points in October 1949, May 1954, April 1958, February 1961, November 1970, March 1975, the summer of 1980, the end of 1981, and mid-1991. The recession of 1981-82 was the most severe since the Great Depression, but it was followed by one of the most robust expansions in American history. 4 Economists, politicians, and others have been puzzled by business cycles since at least the early 19th century. One of the more unusual explanations was proposed by English economist William Stanley Jevons in the 19th century. He believed the ups and downs of an economy were caused by sunspot cycles, which affected agriculture and caused cycles of bad and good harvests. This hypothesis is not taken seriously today. 5 Most business-cycle theories fall into one of two categories. Some economists assert that economies have basic flaws which, for some reason, lead to cycles. Other economists insist that only some form of outside interference can cause swings from high to low unemployment. Unemployment and business failures are the most visible and characteristic signs of a recession. Those who accept the flawed-economy theory usually insist that economies are far too large and complex to operate without a significant degree of government guidance and regulation. Those who hold the opposite view believe that economies are not inherently flawed and that there will be no business cycles as long as there is no outside interference from governments, banks, or other sources. 6 All economies undergo stress and shock from time to time. Natural disasters, such as hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, and earthquakes, can do serious economic damage, but the damage tends to be localized. If a severe freeze wipes out the Florida orange and grapefruit crops, the growers lose money; and the consumers are forced to pay more for these goods, since there are fewer of them. A more severe shock, such as the increases in oil prices during the 1970s, can have far-reaching consequences. But economies adjust to the new situation in a few years. 7 Shifts, changes, and temporary fluctuations do not constitute business cycles. They are adjustments that economies have always endured. The question that must be answered is, what causes a widespread buildup of prosperity followed by a sudden decline? Since money is the connecting link between all economic activities, the answer must be sought there. 8 Economies exist because people exchange goods and services for money. This means that economies are consumer-driven. Everyone is a consumer, though not everyone is a producer. Producers spend money for land, buildings, machinery, resources, and workers. Money circulates through the economy as producers pay owners of land, builders of buildings, makers of machinery, sellers of resources, and a labor force. Products, when they are sold, circulate money back to the producers to keep production going. 9 The money that producers use to start a business comes from investment. Investors believe that a product or service will have a good chance of success, so they want to put money into a business. Some people invest by buying stock, which is ownership in a company. Others invest by making loans--buying bonds issued by the company. Once a business is operating, it gets the bulk of its funds for future growth and continued operations from borrowing. 10 Getting investment money together is the start of a process called capital formation. Investment money is the initial capital. It is used to pay for capital goods: the land, buildings, machinery, and labor force. The source of investment money is savings. A large number of consumers do not spend all of their money in the present. They save part of it. Saving is postponed consumption. Instead of spending today to consume now, some people save in order to be able to consume later. Money set aside in savings earns interest. Both the interest and the original investment can be used for consumption in the future. 11 The money available for investment, especially for loans to business, comes from the savings of all economic units--individuals and organizations. It may be a very large amount, but it is a fairly stable amount. This means there is competition for it. Money, like any commodity, has a price because it is scarce. The price is called interest. If savings exceed demand, interest rates will be low. If demand exceeds savings, interest rates rise. But there is generally a balance between savings and investment in the normal course of economic activity. In other words, supply and demand tend toward equilibrium. 12 Businesses borrow money to expand their enterprises based on the money available for loans. They take it for granted that the money available for lending represents an overall consumer preference for future consumption. Guided by this preference, business operators adjust their plans for the future. 13 If an outside agency interferes with the money supply, the equilibrium between savings and investment is disturbed. This happens in the United States when the Federal Reserve System increases the money supply. Banks have more money to lend, but this money does not come from the original stock of savings. Unfortunately, the businesses that are borrowing do not know this. A loan is a loan, as far as the borrower is concerned. Business expansion, using the new larger supply of money, is no longer being guided by consumer time preferences. But businesses do not know that. Instead of realistic expansion for future needs, they are making malinvestments--a term coined by Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises. These are investments that will not pay off-- somewhat like borrowing to build a factory to make a product no one wants. 14 The process of malinvestment can take several years, as an inflated supply of money courses through the economy and borrowing is easy. New office buildings are constructed, factories are expanded, machinery is purchased, and workers are hired--all to be ready for a great surge of consumer buying power. Meanwhile, prices rise. But the explosion of consumerism never happens. Consumers never voted with their money, by means of savings, to underwrite an excessive expansion. The expansion was due to an inflated money supply. 15 The awareness of this fact gradually works its way through the economy. Businesses realize they are in trouble. They have too many workers, too much machinery, too large inventories, and too much debt. It is time to wind down. So the economy, which has grown like a balloon, begins to contract. People lose their jobs, businesses fail or are sold. Inventories are unloaded at bargain prices. A great inventory adjustment, called a recession, takes place--inventories of goods, machinery, resources, and workers. This progress from money inflation to malinvestment to collapse is the business cycle. 16 Creating a business cycle has never been the goal of the Federal Reserve or any other government agency. Attempts by the federal government to guide and stabilize the economy began early in the 20th century, when, for the first time, unemployment became a political issue. For three quarters of the 19th century, most Americans lived in rural areas and were largely self-employed. Industrialization changed that. Cities grew as job-seekers moved into them. A downturn in the economy that put many people out of work suddenly brought unemployment to the attention of social workers and politicians. 17 The Federal Reserve was very active following World War I in monitoring the money supply. Its inflationary policies probably had a great deal to do with promoting the prosperity of the Twenties and the subsequent collapse. Unemployment remained above 10 percent during the 1930s, in spite of federal programs. After World War II, the federal government deliberately established a full-employment policy to avoid another depression. By then it had become generally accepted by economists and politicians alike that the government could fine-tune the economy through adjustments in tax policy, government spending, and control of the money supply. The writings of British economist John Maynard Keynes were extremely influential in spreading this view (see Keynes, John Maynard). 18 By the 1990s persistently high unemployment had become a significant political problem, and business cycles showed no sign of disappearing. By the mid-1990s, public confidence in economic management by government was declining worldwide. This occurred as economies were undergoing dramatic changes in workforce composition, spurred by the information revolution. II Great Depression 19 United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt, in his first inaugural address, made some attempt to assess the enormous damage: "The withered leaves of industrial enterprise lie on every side; farmers find no markets for their produce; the savings of many years in thousands of families are gone. More important, a host of unemployed citizens face the grim problem of existence, and an equally great number toil with little return." 20 He was speaking of the Great Depression of 1929 to 1940, which began and centered in the United States but spread quickly throughout the industrial world, but his words were inadequate. This economic catastrophe and its impact defied description. What Happened 21 On Oct. 24, 1929, the complete collapse of the stock market began; about 13 million shares of stock were sold. Tuesday, October 29--known ever since as Black Tuesday--extended the damage: more than 16 million shares were sold. The value of most shares fell sharply, leaving financial ruin and panic in its wake. 22 There had been financial panics before, and there have been some since, but never did a collapse in the market have such a devastating and long-term effect. Like a snowball rolling downhill, it gathered momentum and swept away the whole economy before it. Businesses closed, putting millions out of work. Banks failed by the hundreds. Wages for those still fortunate enough to have work fell precipitously. The value of money decreased as the demand for goods declined. 23 Most of the agricultural segment of the economy had been in serious trouble for years. With the arrival of the depression it was nearly eliminated altogether, and the drought that created the 1930s Great Plains Dust Bowl compounded the damage. 24 Government itself was sorely pressed for income at all levels as tax revenues fell, and government at that time was much more limited in its ability to respond to economic crises than it is today. 25 The international structure of world trade collapsed, and each nation sought to protect its own industrial base by imposing high tariffs on imported goods. This only made matters worse. 26 By the fall of 1931 the international gold standard had collapsed, further damaging any hope for the recovery of trade. This started a series of currency devaluations in several countries, because these nations realized that a devalued currency posed at least a temporary advantage in the struggle to find markets for their goods. Social Impact 27 By 1932 United States industrial output had been cut in half. One fourth of the labor force--about 15 million people--was out of work, and there was no such thing as unemployment insurance. Hourly wages had dropped by about 50 percent. Hundreds of banks had failed. Prices for agricultural products dropped to their lowest level since the Civil War. More than 90,000 businesses failed completely. 28 Statistics, however, cannot tell the story of the extraordinary hardships the masses of people endured. For nearly every unemployed person, there were dependents who needed to be fed and housed. Such massive poverty and hunger had never been known in the United States before. Former millionaires stood on street corners trying to sell apples at 5 cents apiece. Hundreds of pitiful shantytowns--called Hoovervilles in honor of the unfortunate Republican president who presided over the disaster--sprang up all over the country to shelter the homeless. People slept under "Hoover blankets"--old newspapers--in the out-of-doors. People waited in bread lines in every city, hoping for something to eat. In 1931 alone more than 20,000 Americans committed suicide. The theme song of the period became 'Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?'. 29 For anyone with a few dimes, depression America was a shopper's paradise. A new home could be bought for less than $3,000. A man's suit cost about $10, a shirt less than 50 cents, and a pair of shoes about $4. Milk was 10 cents a quart, a pound of steak only 29 cents, and a loaf of bread a nickel. For a dime one could go to the movies, buy a nickel bag of popcorn, and even win prizes given away by the theater. That was for those who had dimes. Not many lucky enough to be working had much change to spend after paying rent and buying food. To turn to the government, at least during the Hoover years, was useless. There was no federally financed "safety net" of welfare programs to keep the working class from falling into poverty. Causes 30 The depression of the 1930s shook capitalism to its foundations and shaped the public attitudes of people for generations. The shock was so great because it contradicted long-held beliefs in the unlimited possibilities of expansion. The depression made the Western world ripe for revolution as every political faction in society looked frantically for a cure. Finding a cure without determining the causes, however, was difficult. In fact, no economist has ever thoroughly explained why the disaster of 1929 to 1932 came about. 31 One of the most notable attempts to explain this disaster was made by John Kenneth Galbraith in his book 'The Great Crash, 1929', published in 1955. He pointed to five significant factors: (1) An extremely unequal distribution of incomes limited the consumer goods market. Most people were not making enough money to buy the goods they manufactured. (2) There was an enormous amount of fraud and corruption in big business and in the marketing of stocks and bonds. The prosperity of Wall Street consisted largely of paper that was not backed up by real wealth. (3) The banking structure, made up of too many banks, had acted foolishly in making loans. When bad times came, the loans could not be called in, and many people lost their savings as a result. (4) Foreign nations that had borrowed money from the United States could not repay their loans. This, coupled with high American trade barriers, damaged their economies because they could not send their exports to the United States at a profit. (5) The amount of information on the operation of the whole economy was much less adequate than it is today. People, even experts, were not as able to spot trends in industrial output, investment, consumer buying, and other factors that are now studied closely. Government Response 32 State governments were in no position to do much to aid depression victims, so hard-pressed were they for revenues. The response of the federal government was, at least in the early years, too little and too late. President Herbert Hoover and his aides were convinced that "prosperity is just around the corner." Although the government had been heavily involved in helping large corporations for decades, the idea of direct aid to citizens in distress was regarded with disfavor by many in the Hoover administration. 33 Realistic measures to deal with the depression were undertaken with the installation of Franklin D. Roosevelt in the White House. But even the energy spent on devising new programs was insufficient to undo the depression damage. The economic crisis was not solved until World War II began and triggered huge needs for industrial and agricultural productivity. The Roosevelt New Deal, however, succeeded in putting in place new agencies and policies to try to assure that such a disaster would never happen again. III. Asian financial crisis 34 A financial crisis that gripped much of Asia beginning in the summer of 1997 raised fears of a global economic meltdown. Most of Southeast Asia and Japan saw slumping currencies, devalued stock markets, and a precipitous rise in private debt. Although most of the governments of Asia had no national debt and seemingly sound fiscal policies, the International Monetary Fund was forced to initiate a 40-billion-dollar program to stabilize the currencies of South Korea, Thailand, and Indonesia, whose economies were hit particularly hard by the crisis. In Japan, shortly after the government announced that the country was officially in a recession, the United States intervened to stop a precipitous slide in the value of the Yen by agreeing to buy some $2 billion worth of the Japanese currency. In doing so, the United States hoped to increase the value of the Yen, which had fallen to its lowest point in some eight years. 35 The efforts to stem a global economic crisis did little to stabilize the domestic situation in Indonesia, however. After 30 years in power, President Suharto was forced to step down in May 1998 in the wake of widespread rioting that followed sharp price increases caused by a drastic devaluation of the rupiah. The effects of the crisis lingered through 1998; by 1999, however, analysts saw signs that the economies of Asia were beginning to recover. reference Great Plains Great Plains, extensive grassland region on the continental slope of central North America. They extend from the Canadian provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba south through W central United States into W Texas. In the United States the Plains include parts of North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Texas. Dust Bowl Dust Bowl, the name given to areas of the U.S. prairie states that suffered ecological devastation in the 1930s and then to a lesser extent in the mid-1950s. The problem began during World War I, when the high price of wheat and the needs of Allied troops encouraged farmers to grow more wheat by plowing and seeding areas in prairie states, such as Kansas, Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico, which were formerly used only for grazing. After years of adequate yields, livestock were returned to graze the areas, and their hooves pulverized the unprotected soil. In 1934 strong winds blew the soil into huge clouds, and in the succeeding years, from December to May, the dust storms recurred. Crops and pasture lands were ruined by the harsh storms, which also proved a severe health hazard. The uprooting, poverty, and human suffering caused during this period is notably portrayed in John Steinbeck <http://www.infoplease.com/ce6/people/A0846620.html>'s The Grapes of Wrath. Through later governmental intervention and methods of erosion-prevention farming, the Dust Bowl phenomenon has been virtually eliminated, thus left a historic reference.