Ben and Jerry`s Case Study

advertisement

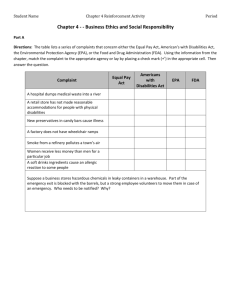

Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield Case Study When Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield invested $5.00 in a correspondence course on how to make ice cream, they had no idea their dream of owning and operating a small-time homemade ice cream parlor in rural America would, in the year, grow to include: Ice cream stores in 35 states A headquarters that is the second largest tourist attraction in Vermont A shop in Russia Ben & Jerry’s Homemade, Inc., was founded in 1978 by the young, eager entrepreneurs who managed to come up with $12,000.00 ($4,000.00 of which came from a skeptical bank). They set up shop in an abandoned gas station they renovated themselves in Burlington, Vermont. Last year, the company had sales of $30 million and ranks number three nationally in the explosively growing super-premium ice cream market. (Haagen Dazs owned by Pillsbury is number one and Kraft’s Frusen Gladje is number two.) “We weren’t starting out to create an ice cream empire. We just wanted to have a homemade ice cream parlor. We never saw ourselves – and still don’t see ourselves as businessmen. But as ice cream men,” said 37-year-old Ben Cohen. Friends since seventh grade, the two Merrick, Long Island, New York teenagers decided in college that it would be “fun to work in a business we created together,” said Ben. “Our entire motivation has to be our own bosses. We saw ourselves as having fun while working together,” said Jerry. The ultimate question one has to answer in starting up a small business is, according to Ben, “Would I rather work 40 to 50 hours a week for a company I don’t really care about or believe in, or 90 to 100 hours a week working for a company I do care about and in which I do believe?” In setting their sight on what type of company to start up, Ben and Jerry who describe themselves as “former fat and slow guys always last in gym class,” said they always thought a lot about food. “We looked into bagel making but the equipment was too expensive,” said Ben. “Penn State University offered the ice cream correspondence course. We had always been ice cream fanatics, so that was it!” Jerry soon left his job as a research lab assistant and Ben, who has worked in a range of jobs from taxi driver in New York City to telephone directory delivery man and Pinkerton guard to crafts teacher, opened up the company “as a total lark” they said. “We wanted to do something interesting and we wanted to express ourselves. We also wanted to have contact with the public,” said Ben. They advise entrepreneurs to be “self-starters because you must create the structure of your company. There is no one else around to do it. You have to be self-motivated to create and do what needs to be done in order to make things happen.” The ice cream makers suggest their start up could be viewed as a “Don’t Do This” chapter in a book on how to start your own business. “The experts told us we were doing everything wrong,” said Ben. “We soon learned to take the advice of experts with a shaker full of salt. “We went to banks and to the Small Business Administration for a loan. We were at an extreme disadvantage as we had no experience in business or with ice cream manufacturing. We didn’t have any retail experience either. “We didn’t have any assets or collateral but on our loan application we listed a 1969 Ford, an old sailboat, and Jerry’s couch,” said Ben. The Small Business Administration rejected their request for a loan because they failed to satisfy the location requirements needed by the agency. “Location is the most important thing in a retail business. It can be discouraging when you’re ready to open and you can’t find the right spot,” said Ben. The entrepreneurs had tried to find locations across the border in Saratoga and Lake George, New York. Local competition beat them to it, so they moved their dream to Vermont. “These were very though times. I almost stopped, almost gave up,” said Ben. The two persevered and found the old gas station in Burlington. Marketing experts predicted that a higher priced ice cream in rural, unpopulated, low-income based Vermont would never succeed. But Ben and Jerry viewed Vermont as having distinct advantages: “The state was rich in dairy products and had an excellent reputation for these products. The quality of life was and is very high, even if the population and income might be low.” “Also, we could become a big fish in a little pond. We eventually saw Vermont as our small test market,” said Ben, who likens the Burlington opening to a Broadway show that first that first opens out of town. To secure the $4,000.00 bank loan, Ben and Jerry put together a 26-page business plan. “We did some research on other ice cream parlors in the Northeast and put in a few chart and graphs on ice cream consumption. “It looked pretty good,” said Jerry. Ben’s advice to the first time small business person is “to start. Just start. Start on a small scale. Out of you house, your backyard, your garage, mailbox, whatever, but start. Then, go with your own vision. If you’re in retailing or marketing, be personable. I think we succeeded because people are looking to buy a product or service from someone they can relate to rather than a huge, anonymous corporate structure.” Jerry added that “it’s important to do something that reflects who you are as a person. Be true to yourself rather than try and do what is expected of you.” “You have to be willing to do anything that needs to be done. You can’t expect to find an electrician at 2 a.m. to fix that broken freezer. On the bright side, you’ll have an amazing chance to do what you want to do. Your business will become what you are as well as what you want it to be,” said Jerry. The -20˚F temperature winters in Vermont actually worked to catapult Ben and Jerry to success and national reach. “There simply was no market during those cold winters. No customers were coming into the shop in the wintertime. We had to do something to boost our sales, so we decided to bulk package the ice cream in containers for nearby restaurants and ski resorts. We packaged it in pint sized containers for the Mom and Pop food shop, “said Jerry. Ben delivered the product in his Volkswagen squareback, picking up a few speeding tickets to get the product to the shops while it was still frozen. “The retailers seemed to be rooting us. They seemed to like our dedication to our business, “said Ben. Gradually, positive word-of-mouth for Ben and Jerry’s homemade ice cream spread and retailers and restaurants began calling in hefty orders for the packaged products. “We needed to raise money to expand our operation to meet the demand,” said Ben. “We were working ten hour shifts to churn out all the ice cream we could during this unexpected boom.” The entrepreneurs wanted to create Vermont’s first public stock offering. The proposal they created would enable a citizen of Vermont to buy a share of the company for a relatively low minimum - $126.00 – as compared to one or two thousand. For this sum, a Vermonter could become part owner-part investor in Ben and Jerry’s business. Accountants, lawyers and bankers told Ben and Jerry it would never work and suggested they turn to venture capitalists. “We knew venture capitalists would pour big bucks into the operation and would continue to do so as a protection on their investment,” said Ben. “We had heard of companies with fancy equipment, investors and company cars – and a year later they were bankrupt. We decided to stick with our small steps,” said Ben. The Vermont public stock offering turned out to be a huge success, raising enough capital for Ben and Jerry to expand to their current facility in Waterbury, Vermont. The facility is ranked as the second largest tourist attraction in the state (the Shelburne Museum is number one). “We had a vision of making the plant a centre for manufacturing and marketing. Sort of like a winery where there are tours, sampling of the product, and a shop. We open up the grounds for visitor’s picnics and use the facility to host annual outdoor meeting for our shareholders complete with field day type competitions, food, music and other entertainments,” said Ben. Ben & Jerry’s has always been a community-oriented business, attempting to give something back to the community and customers who supported the company. As the business has grown, so too has Ben & Jerry’s commitment to being a socially responsible company. The company donates 7 ½ percent of its pre-tax income to the Ben & Jerry’s Foundation. The foundation supports communityoriented projects through grants and loans. Jerry, who is president of the foundation, said Ben & Jerry’s has recently sponsored a rap video for an inner-city high school history class in Boston and presented the World Series of Beep Baseball, baseball for the blind, in which the ball beeps and the base buzz. The company has also offered to adopt-a-subway station in New York City volunteering to pay for its clean-up and maintenance with a 6 crew team. To date, the company has not been permitted to begin the cleanup campaign because of union snarl-ups. “We see the clean-up campaign as useful to the city and we would be happy to do it in lieu of an estimated $250,000 ad campaign we had been thinking of starting in New York City. It’s a plan that would really benefit everyone,” said Ben, who hasn’t yet given up on the idea. Meanwhile, Ben and Jerry have started construction on an indoor garden and exhibition space at the new Manhattan branch of the Museum of American Folk Art on the Upper West Side near Lincoln Center. The museum will be free and open to the public. A shop in Moscow opened in 1989. The purpose of which is “to foster an exchange between Russian and American college students,” said Ben. “Profits from the sale of ice cream in the shop will help to bring Russian student to the University of Vermont. They will work part-time in the Burlington Ben & Jerry’s and learn about ice cream making and entrepreneurship,” said Ben. In the next few years, Ben and Jerry will devote their free time to the “1 Percent For Peace” project they are initiating. A grass roots movement with the goal of having 1 percent of the annual military budget devoted to peaceful exchange programs and activities all over the world, Ben and Jerry plan to publicize the plan on their new “Peace Pops.” If successful the plan would generate $3 billion a year for the cause. “We want our business to be a model for what a socially responsible business can be in the United States. We want to demonstrate that you can have a profitable operation and still help people in your community,” said Ben.