Turnout in US elections

advertisement

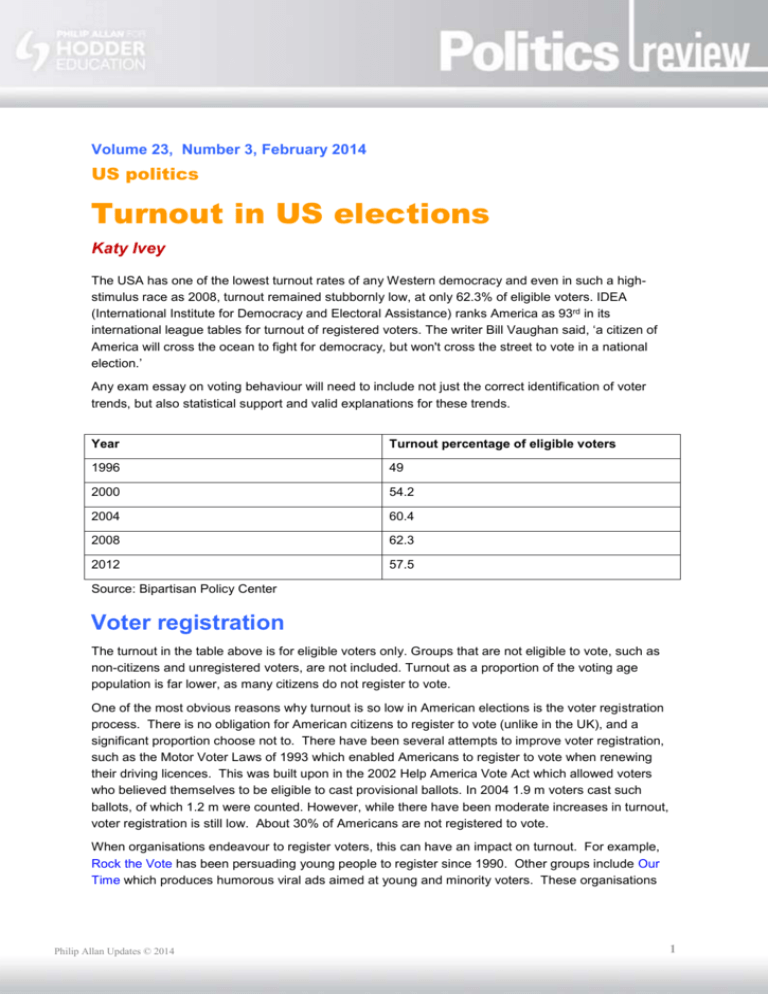

Volume 23, Number 3, February 2014 US politics Turnout in US elections Katy Ivey The USA has one of the lowest turnout rates of any Western democracy and even in such a highstimulus race as 2008, turnout remained stubbornly low, at only 62.3% of eligible voters. IDEA (International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance) ranks America as 93rd in its international league tables for turnout of registered voters. The writer Bill Vaughan said, ‘a citizen of America will cross the ocean to fight for democracy, but won't cross the street to vote in a national election.’ Any exam essay on voting behaviour will need to include not just the correct identification of voter trends, but also statistical support and valid explanations for these trends. Year Turnout percentage of eligible voters 1996 49 2000 54.2 2004 60.4 2008 62.3 2012 57.5 Source: Bipartisan Policy Center Voter registration The turnout in the table above is for eligible voters only. Groups that are not eligible to vote, such as non-citizens and unregistered voters, are not included. Turnout as a proportion of the voting age population is far lower, as many citizens do not register to vote. One of the most obvious reasons why turnout is so low in American elections is the voter registration process. There is no obligation for American citizens to register to vote (unlike in the UK), and a significant proportion choose not to. There have been several attempts to improve voter registration, such as the Motor Voter Laws of 1993 which enabled Americans to register to vote when renewing their driving licences. This was built upon in the 2002 Help America Vote Act which allowed voters who believed themselves to be eligible to cast provisional ballots. In 2004 1.9 m voters cast such ballots, of which 1.2 m were counted. However, while there have been moderate increases in turnout, voter registration is still low. About 30% of Americans are not registered to vote. When organisations endeavour to register voters, this can have an impact on turnout. For example, Rock the Vote has been persuading young people to register since 1990. Other groups include Our Time which produces humorous viral ads aimed at young and minority voters. These organisations Philip Allan Updates © 2014 1 seem to have had some success — youth turnout was 50% in both 2008 and 2012, the highest it had been since 1972. Campaigning It is unlikely that the increasing ease with which Americans can register to vote fully explains the increase in turnout from 1996 to 2008. There has always been variance in the ease of registration in different states (in Maine, Minnesota, and Wisconsin voters can register on election day) but turnout has still been low even in those states where it is deemed ‘easy’ to register. The 2008 campaign encouraged other under-voting groups to turn out. This was most evident in the African-American population, where turnout was 65%. The impact of Obama’s candidacy offers some explanation for this. High-stimulus elections where the economy is wavering and there are interesting candidates (such as 1992 and 2008) usually result in increased turnout. The reverse is true for elections held in times of ‘peace and prosperity’ (1996), where voters show no interest in altering the status quo (described by some psephologists as ‘hapathy’). Both parties have sought to encourage turnout among their supporters. In 2004 Republicans, under the direction of Karl Rove, worked to ‘energise the base’ of the Republican Party by encouraging state-level referenda on ‘wedge issues’ such as gay marriage which motivated Republican turnout. It was notable that even in states that Kerry won (such as Michigan), socially conservative voters still turned out in large enough numbers to ensure the failure of gay marriage referenda. In 2008 and 2012 the Democrats used innovative social networking techniques (such as Dashboard) to help to register new voters. This proved pivotal in 2012: while Obama only secured the votes of 92% of registered Democrats, they turned out in greater numbers than Republicans.. Differential Abstention The worry for psephologists is that turnout is not uniform. Differential abstention describes the disparity in turnout across social groups. While ‘hapathy’ could explain low turnout, the people who do not vote are unlikely to be ‘happy’ as well as ‘apathetic’. A study of these disparities found that 86% of people with incomes above $75,000 voted in presidential elections as compared with 52% of people with incomes under $15,000. This has meant that US politicians, whose main concern is the ‘folks back home’, tend to focus on the issues most affecting those in higher-income groups. It used to be the case that African-American turnout was low, although the US Census Bureau reported that African-American turnout surpassed the white turnout for the first time in 2012. Undervoting by African-Americans was due to Jim Crow laws prior to 1965. In addition many states bar convicted felons from voting (which disproportionately penalises African –American males). Hispanic voters also tend to have low turnout, with only 49% voting in 2008, for many of the same reasons. Abstention varies from election to election. While young and minority voters turned out in great numbers in 2008, the 2010 midterms saw a huge decrease in turnout. White turnout rates fell 21 percentage points from 2008 to 2010, while African-American turnout decreased 25 percentage points and Latino turnout fell 23 percentage points. This is partially because in 2008 Obama benefited from prospective voting whereby people turned out on the promise of change. This was not repeated in 2010 as Obama had failed to deliver on his promises. Philip Allan Updates © 2014 2 Battleground states usually have a higher turnout, perhaps due to the concentration of campaign activity in these states. Iowa, Nevada and Wisconsin increased turnout from 2008 and 2012 due to their status as ‘battlegrounds’. Safe states tend to get ignored by candidates — in 2000 there were13 states that were visited by neither presidential candidate. States that lose battleground status tend to see a decrease in turnout. For example, in New Mexico turnout declined 2008–2012. Continuing obstacles The white population of the USA is in decline. This is of some concern to Republicans who receive the majority of the white vote. Each state in the USA has the ability to draw up its own electoral laws, so long as they are not in conflict with the provisions of the Constitution. This has allowed states to pass laws that purport to prevent voter fraud, but are designed to penalise minority voters (who largely favour the Democrats). Many states have passed voter ID laws which require voters to produce valid identification when registering to vote and/or voting. Those on low incomes and from minority populations are least likely to have ID and so these laws discourage turnout from these groups. The 1965 Voting Rights Act required Congress to approve any changes to voting laws in states with a history of discriminating against minorities. This part of the Act was struck down by the Supreme Court in 2013. Nonetheless, given that African-American turnout increased in 2012, the fears of those campaigning against voter ID laws have yet to be realised. Many Americans are hostile to government interference in their lives, and this includes registering and turning out to vote. In a country that prides itself on its democracy, surely it is a democratic right to abstain from voting as it is to ‘cross the street to vote in a national election’? Katy Ivey teaches politics at Stroud High School and is an experienced examiner. Philip Allan Updates © 2014 3