Pearl Harbor Paper Proposal

advertisement

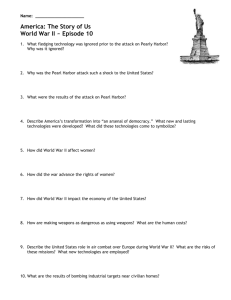

Fear and Paranoia: America’s Reaction to Pearl Harbor On December 7, 1941, Japan launched a surprise air raid on the U.S. military base Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. The attack came as a shock to many Americans because the War raging in Europe and in Asia seemed so far from home. However, there was now an attack on American soil and this woke the American people up to the World War that was occurring. In this paper, I will examine the reactions from both the U.S. government and the citizens, arguing that this attack caused both to react out of vengeance, fear, and paranoia. This topic is important because it shows how people react in times of tragedy. In the aftermath of an unprovoked attack on a country, its government and citizens will want revenge, but also its people will be afraid and paranoid. This will cause rash decisions which will most likely hurt innocent people, for example Japanese Americans in internment camps. The initial reaction to Pearl Harbor was the defense of the military base and the measures taken by the American soldiers. Analysis of this reaction provides the reader with more context and a better understanding of the chaos that was Pearl Harbor. The primary source for these reactions will be accounts from veterans of the Pearl Harbor attack.1 The U.S. government’s reaction to Pearl Harbor is needed because its decisions affected both America and the entire world. The first primary source is President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s speech given to congress, stating that Japan had attacked the United States in a surprise offense and the United States needed to declare war to protect itself.2 That source ties into the fear and vengeance reactions from the United State’s government because Japan had angered, shocked, and embarrassed the U.S. The next primary source from the U.S. government deals more with the paranoia-based reaction. It is an executive order from President Roosevelt stating that it is legal to take any Arthur R. Lee, “Recollections,” American History 33, no. 5 (December 1998): 58. Franklin D. Roosevelt, “A Date that Will Live in Infamy,” Speech given to Congress to Declare War on Japan, Washington D.C., December 8, 1941. 1 2 American citizen of Japanese descent and put them into internment camps.3 This is important because this is the piece of legislation that took Japanese Americans’ rights away. Overall, these sources show the U.S. government was very quick to react to the situation, and in many ways it reacted out of fear, aggression, and paranoia. The American public’s reactions, as a whole, were not much different from their government’s. Their initial reaction was they wanted to get revenge on the Japanese for the unprovoked attack. The primary source used to describe this is a recording done by the Library of Congress the day after the attack. It is a series of interviews with regular American citizens on the street and their thoughts on the Pearl Harbor attack.4 The running theme is of revenge, shock, and fear that they will attack again. Another primary source is veterans remembering their reactions to the event.5 Some are that of the actual event and others are their reactions after the fact. Both of these sources are important because it shows the reactions of everyday Americans and veterans, who the event affected the most. The United States as a whole, citizens and the government, were both incredibly shocked by this incident because there was a feeling of separation these two groups felt from this war. There is an ocean separating the U.S. from both Asia and Europe. When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor it was a blow to America’s feeling of invincibility and safety. The Japanese Americans’ reactions, who were put into internment camps and were discriminated against, need to be studied because they took the brunt force of the paranoia induced reactions from the United States’ citizens and government. Studying their experiences in the internment camps will give context to the paranoia running rampant throughout America. A primary source that would be necessary for this would be letters from Japanese Americans Exec. Order No. 9066, 3 C.F.R. 1092-1093 (1942). American Citizens, interview by Liane Hansen, Weekend Edition Sunday, NPR, December 10, 2000. 5 Corey Paul, “Veteran Remembers Pearl Harbor, WWII,” Odessa American, December 7, 2012. 3 4 during this time. One example is a letter from a Japanese American from inside an internment camp.6 It explains the poor conditions and how they were taken from their homes forcefully and put into these camps. Another source is of a woman remembering back to her time spent in the internment camp as a little girl.7 Both sources explain how their rights were taken away and how they were treated as the enemy instead of a fellow American citizen. Seeing the situation from the Japanese American’s point of view makes it easier to fully understand the paranoia and fear that was in America at the time. On the day of the attack, a Japanese pilot crash landed on the Hawaiian Island of Ni’ihau. He then gained the support of some American citizens of Japanese descent and tried to escape. He was quickly stopped, however; this incident fueled anti-Japanese ideas in the U.S. It also gave the sense that any American of Japanese descent would turn on America. This incident coupled with Pearl Harbor caused the United States government and citizens to react out of fear, revenge, and paranoia. The U.S. wanted revenge against the Japanese for their surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. The government and citizens were afraid and paranoid of a Japanese uprising in the U.S. These fears fueled anti-Japanese actions and made it legal for the American government to take Japanese American rights away and put them into internment camps. This is an important topic to study because it shows the evil things people do when they are afraid or paranoid after a major catastrophic event. The primary sources used will help explain why people reacted this way and what they were thinking at the time. 6 Frank J. Battisti, Difficult Decisions During Wartime: A Letter from a Non-Alien in an Internment Camp to a Friend Back Home, Edited by Frank H. Wu, Case Western Reserve Law Review, 2004. 7 Akari Hatanaka, “I’m American, No Matter What,” Weekly Reader News-Senior 82, no. 24 (May 2004): 5. Bibliography Primary Sources American Citizens, interview by Liane Hansen, Weekend Edition Sunday, NPR, December 10, 2000. Battisti, Frank J. Difficult Decisions During Wartime: A Letter from a Non-Alien in an Internment Camp to a Friend Back Home. Edited by Frank H. Wu. Case Western Reserve Law Review, 2004. Congressional Record. Senate and House on Declaration of State of War with Japan. (December 8, 1941): 9504-9539. Exec. Order No. 9066, 3 C.F.R. 1092-1093 (1942). Hatanaka, Akari. “I’m American, No Matter What,” Weekly Reader News-Senior 82, no. 24 (May 2004): 5. Ketchum, Richard. “Yesterday, December 7, 1941...” American Heritage 40, no. 7 (November 11, 1989): 52. Lee, Arthur R. “Recollections.” American History 33, no. 5 (December 1998): 58. Paul, Corey. “Veteran Remembers Pearl Harbor, WWII,” Odessa American, December 7, 2012. Roosevelt, Franklin D. “A Date that Will Live in Infamy.” Speech given to Congress to Declare War on Japan, Washington D.C., December 8, 1941. Scott, Anne Firor. “One Woman’s Experience of World War II.” Journal of American History 77, no. 2 (September 1990): 556-562. Secondary Sources Clarke, Thurston. Pearl Harbor Ghosts: The Legacy of December 7, 1941. New York: Ballantine Books, 2001. Conroy, Hillary., Wray, Harry. Pearl Harbor Reexamined. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1990 Darling, Ian. “Shock Pushed U.S. into War.” Waterloo (ON) The Record, December 7, 2011. Duus, Masayo. Tokyo Rose: Orphan of the Pacific. New York: Kodansha International, 1979. Grapes, Brian J. Japanese American Internment Camps. San Diego, California: Greenhaven Press, 2001 Hallstead, William. “The Niihau Incident.” World War II 14, no. 5 (January 2000): 38. Hotta, Eri. Japan 1941: Countdown to Infamy. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013. Kawashima, Yasuhide. The Tokyo Rose Case: Treason on Trial. Lawrence, Kansas : University Press of Kansas, 2013. Lind, W. Andrew. Hawaii’s Japanese: An Experiment in Democracy. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1946. Miyamoto, S. Frank. “The Forced Evacuation of the Japanese Minority during World War II.” Journal of Social Issues 29, no. 2 (June 1973): 11-31. PBS. “Japan Invades the Aleutian Islands.” American Experience. Accessed February 23, 2015. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/general-article/alaska-japan/ Rosenberg, Emily S. A Date Which will Live: Pearl Harbor in the American Memory. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2003. Toland, John. Infamy: Pearl Harbor and its Aftermath. New York: Doubleday and Company, Inc, 1982. Weintraub, Stanley. Pearl Harbor Christmas: A World at War, December 1941. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press, 2011. Wilson, Theodore A., Townsend, Kenneth William. “Bombing of Pearl Harbor.” Salem Press Encyclopedia. (January 2012): 4