Cuba: Revolution, Resistance And Globalisation

advertisement

Latin America

R. James Ferguson © 2006

Lecture 4:

Cuba: Revolution, Resistance And Globalisation

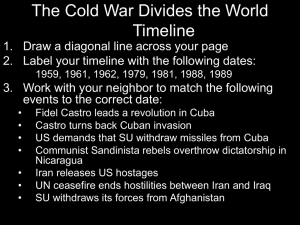

Overview: 1. Introduction: A Country With Unique Forms of Internationalisation

2. History: Diaspora and Cultural Fusion

3. Early U.S. Involvement in Cuban Affairs

4. The Revolutionary Legacy of the 19th Century

5. Castro's Revolution

6. Conflict and Containment

7. The Case of Elian Gonzalez

8. Modern Cuba: A Unique Culture Playing A Unique Strategy

9. Survival Strategies (Seminar)

10. Bibliography and Further Resources

1. Introduction: A Country With Unique Forms of Internationalisation

Cuba is the largest of the Caribbean Islands and lies strategically at the entrance

to the Gulf of Mexico, controlling approaches to Mexico, the Mississippi valley and

western Florida (MacGaffey 1962, p1). More importantly, it is an island which

developed its own unique cultural and political system that would involve it in a

complex relationship with the U.S. and then find itself at the forefront of the Cold

War superpower contest. Since 1992, the country faced a new challenge: how a

socialist country can position itself in the face of globalisation and an ongoing

economic embargo from the U.S. These pressures have forced the country into

innovative forms of resistance and survival, and, ironically, helped maintain the

regime of Fidel Castro. However, the future nature of a post-embargo, post-Castro

Cuba remains to be resolved.

The country has a fair agricultural resource base, with main crops including sugar,

coffee, and tobacco, and secondary crops including pineapples, bananas, rice and

corn. Alongside these products, Cuba also some mineral resources: iron, nickel,

copper, manganese, tungsten, naphtha, asphalt and a certain amount of petroleum and

gas, which provides only around 38% of the islands energy needs (MacGaffey 1962,

p2; Oil Daily 2002). The island also has industrial potential in sugar refining and

related products, food processing, pharmaceuticals, and industrial chemicals. It has a

relatively well-educated population, a strong tourist industry, and a relatively strong

medical system (see below).

Lecture 4

1

Cuba (Courtesy PCL Map Collection)

2. History: Diaspora and Cultural Fusion

Cuba was first discovered by the West with Columbus' voyage of 1496, though the

island was not permanently settled by Spain until 1511 (MacGaffey 1962, p2).

Cuba had its own unique indigenous people before the arrival of Columbus to the

island, but their relatively small numbers (perhaps 60,000) were eroded by the impact

of European settlement, disease, and famine (Thomas 1971, p21). In spite of

attempted rebellions in 1524-32 and 1538-44 these people were unable to sustain

themselves as an independent society (August 1999, p43). Nonetheless, they formed

one of the elements in modern Cuban culture, in part because the Spanish at first

showed less prejudice towards them racially than towards Africans who mainly

arrived as slaves. Many indigenous natives 'were undoubtedly absorbed in Cuba as

elsewhere into Spanish families and, because of the whiteness of their skin, were

regarded as Spanish (or creoles)' (Thomas 1971, p21). Since 80% of Spaniards who

came to the island in the 18th century were males, intermarriage with other races was

quite common (August 1999, p66). In time the term Creole would come to indicate

any person who was a permanent resident in Cuba and took Cuban interests to

heart, in contrast to those who still felt linked to peninsula Spain (August 1999, p51).

Some leading creole families who had achieved noble status moved from beef and

tobacco production into sugar, and were owners of thousands of slaves (Thomas 1971,

p32, pp46-47). Creole families such as the Herreras and Núñez de Castillo were

ennobled and controlled large estates (Thomas 1971, p47). Although various forms of

racism and discrimination would develop, especially against the descendants of black

slaves, there was no formal apartheid and discrimination in most public places,

schools and the public service were outlawed by 1893 (Thomas 1971, p293). Race

issues, however, continue to remain a challenge to the socialist ideals of modern

Lecture 4

2

Cuba. Contemporary prejudice is more subtly oriented on the basis of appearance and

education. Exclusion here is sometime explained on the basis of aesthetic and cultural

factors, with the loose criteria of buena presencia (good appearance) acting as little

more than a rationalisation of prejudice against those of dark appearance, even though

up to 60% of Cubans have a "significant" degree of African ancestry (Hansing 2001,

pp743-744; de la Fuente 1998, p7; Moore 1997, p13).

The early Cuban economy for a time was based on cattle, hides, and some extraction

of gold, though the economy of the islands declined during the 16th century

(MacGaffey 1962, p4) until new plantation crops began to be developed. The

Spanish in Cuba, however, soon found that they needed massive imports of labour for

their diverse plantations, especially slaves from the west coasts of Africa (see

Thompson 1987). The demand for labour on tobacco, coffee (Topik 2000; Thomas

1971, pp132-133) and especially sugar plantations pushed up the demand for slaves

(Williamson 1992, p436; Jamieson 2001), even when their import was limited at first

by Spanish state monopolies and later on by the British fleet when England outlawed

the practice of slavery from the early 19th century, and tried to intercept the slaving

ships leaving Africa (Thomas 1971, p33, p93, p94).

The African diaspora, of course, was one of the crucial shaping events of the modern

world, and a total of some 15 million people were carried to the Americas between the

sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, profoundly shaping the structure of both American

and some African nations (Thomas 1971, pp282-284; see further Thompson 1987).

From the 18th century onwards, it was their labour on plantations that formed the

backbone of the Cuban economy. Sugar production, (sugar cane was first introduced

into the island in the 1520s, August 1999, p46), required a large and ready supply of

slaves, whose procurement amounted to between one third and half the entire cost of

founding a plantation (Thomas 1971, p30). Between 1763 and 1862 some 750,000

slaves were brought into Cuba (August 1999, p47). As a result, during the 19th century

Africans or racially mixed groups formed between 50-60% of the population of the

island (Thomas 1971, p168). ). Slave populations had arrived from most areas of the

west coast of Africa, including Nigerian ports, the Bight of Benin, Dahomey, Lagos,

the Congo, and the Gold Coast (Thomas 1971, pp158-159). Sizeable cultural grouping

included the Ibos, Yorubas and Congolese tribes (Thomas 1971, p40). By the 1820s

Cuba had become a rich colony and for a time 'the largest sugar producer in the

world', pulling ahead of other islands such as Jamaica (Thomas 1971, p61). Other

products, such as copper, beef, and hides were soon moved in a very secondary role in

the economy.

There were some important differences between slavery in Cuba than in other parts of

the free world. Although conditions were generally harsh, especially on the sugar

plantations, local law meant that slaves could buy their own freedom, and that in time

a sizeable Afro-Cuban community emerged in the island, creating their own culture,

religion, literature, and music (Thomas 1971, pp36-37). As a result, though the island

retained a Spanish nobility and a growing immigration of peasants and workers from

Spain in the late 19th century, Cuba thus soon developed a sizeable minority of free

Africans and Afro-Cubans who formed an important part of the national

identity of the island. During the nineteenth century persons of mixed racial

backgrounds sometimes managed to secure places in universities, some became

Lecture 4

3

professors and others entered the bureaucracy, while some poets of African or mixed

origin, such as Plácido, became famous (Thomas 1971, p172)..

One important aspect of this emerging culture was the way the Roman Catholic

Church at first tried to allow a gradual conversion of the customs of natives, tolerating

the syncretism between Catholic and indigenous beliefs. From the early 18th

century this led to the creation of African cofradías (religious brotherhoods), whose

unique blend of religion was most evident during festival and feast days, e.g. at the

Día de los Reyes, otherwise known as Epiphany (Thomas 1971, pp39-40). Eventually

this would lead to more Africanised forms of religion such as Santería. In the

modern period, as well, syncretic religions based in part on African traditions,

especially Santería (also known as La Regla de Ocha), have become extremely

popular in Cuba (Moore 1997, p226). This is one area of personal freedom that has

not been effectively constrained by state ideology. Santería is often expressed through

invoking, playing for, singing to, or writing songs about the Yoruba gods, e.g. the

songs Bilongo, Mayeya and Devuélveme la voz (Delgado 1999). From the 1990s the

cult of Ifa (an Afro-Cuban diviner cult) has also become prestigious and popular

among some groups, perhaps operating in the context of economic crisis and

competition among religious systems (see Holbraad 2004).

Even from an early stage the diverse elements in the island began to interact in

creating a unique music, dance and oral culture, in part as Africans were drawn into

Spanish festivals and the 'fiestas partly Africanized' (Thomas 1971, p40). In time this

led to the evolution of complex Afro-Cuban rituals such as the Abakuá, which

attracted participants from all racial groups (Thomas 1971, p199). Particular dance

forms evolved, such as the chachá, the rumba and the babul (an African dance evolve

in Cuba's Oriente province, Thomas 1971, p178). It was on this basis that

contemporary musical forms evolved, including a number of unique song forms such

as the son and trova (Lam 2000; Sweeney 2001; Yanow 2000). African magic and

religion, too, survived in modified forms, sometimes focused on secret societies and

clubs, while apparently overseers treated African medicine men with great care

(Thomas 1971, p177, p180).

Cuba's first moves towards asserting a character independent of their status as a

Spanish colony were driven by two factors: the effort to improve the economy of the

island, and a sense that Cuba had its own culture, history and place in the world.

Indigenous Cuban planters developed the idea of a Cuban 'liberal economy' (Thomas

1971, p73). They set much of the subsequent train of Cuban history on track by

creating large 'efficient' plantations. In modernising the sugar plantations, however,

the Cubans created an ongoing demand for slaves (Thomas 1971, p84), a demand

which in the end could only lay the seeds of revolt and Cuban nationalism. Already

in 1791 Saint Domingue (Haiti) underwent the first successful slave revolt, and was

an inspiration to slaves and freed slaves throughout the region. Slave revolts were

suppressed in Cuba in 1843-1844 (Thomas 1971, pp204-205).

Sugar in the long run also created the demand for the construction of railways, whose

price could only drop once cheap methods (the Bessemer process) for the production

of steel were invented (Thomas 1971, p273). By the end of the 19th century, it

emerged that the use of railways and new mill technology meant that indentured

Chinese labour (over 150,000 were brought in, though most who survived returned

Lecture 4

4

home) and contracted Spanish peasants were cheaper suppliers (Thomas 1971,

p122, pp185-188, pp274-276). The treatment of these groups was extremely poor, and

in many ways these workers were tied to cycles of poverty and debt that would also

force new revolutions on the island. Ironically, too, the emancipados (legally freed

slaves due to the intervention of the British navy against slavers) of the nineteenth

century were sometimes treated horribly: they were often put into forced labour and

literally worked to death over a seven period, since they had then had no residual

value as property to their overseers (Thomas 1971, p181, pp201-202).

3. Early U.S. Involvement in Cuban Affairs

U.S. involvement in Latin American issues goes back prior to American

independence. Part of the causes of the American revolution lay in economic interests,

in particular the desire to trade freely outside British mandates, including the wish to

trade with Cuba and the French West Indies (Thomas 1971, p66). In the late 18th

century Britain was still concerned to counter Spanish and French interests in the

Americas. Furthermore, North American merchants became major traders with Cuba

from the early 19th century, including even imports of food supplies (Thomas 1971,

pp86-87, p194). In spite of official bans, U.S. ships were prominent in the early 19th

century slave trade, using the American flag in order to resist inspections by the

British navy, though this changed after 1860 with the election of President Abraham

Lincoln (Thomas 1971, p203, pp230-231). By the mid-19th century the majority of

machinery, railway equipment, loans and investments in the Cuban sugar industry

also came from the U.S. (Thomas 1971, p209). The U.S. became the dominate trade

partner with Cuba in the late 19th century, while Cuba was America's main South

and Central American trading partner, with Cuba for a time accounting for 10% of the

U.S.'s total imports (Thomas 1971, pp288-289).

The U.S. was keen to avoid radical solutions in Cuba, and in particular suggested that

the national and revolutionary movements sweeping South America should not

make their way into Cuba and Puerto Rico, while during the 1820s and 1830s the U.S.

was still willing to see regional dependence on a relatively weak Spain (Thomas 1971,

p104). Yet shortly thereafter independence would be recognised by Spain for most

Latin American countries from 1836 down till 1894, with Brazil establishing its

independence from Portugal by 1822 (August 1999, p45).

Indeed, the U.S. from the early 19th century saw control of Cuba as very much bound

up with her own regional security. The Monroe Doctrine of 1823 had already

developed the idea that the Americas should not be drawn into European conflicts or

penetrated by new patterns of European imperialism or military intervention

(MacGaffey & Barnett 1962, p317). The U.S. had expanded both westward and

southward only recently. California and New Mexico (after the U.S. war with

Mexico of 1846-1848), Louisiana (purchased in 1804), Texas (1845), Florida

(purchased in 1819) and Alaska (purchased in 1867) had been secured either by

purchase, settlement, or as the result of conflict which drew U.S. interests outwards.

It was in this context that many plans were formulated for the U.S. purchase of

Cuba, the first thought up in 1839 by Nicolas Trist, U.S. consul in Havana, but

repeated by different groups in 1847-1848, and again in 1854 and 1857-8, offering

Lecture 4

5

US$100-130 million to Spain for the deal (Thomas 1971, p199, pp211-214, p223).

Other offers included loans to Cuba that would pay off Spanish debts up to US$400

million (Thomas 1971, p222). A last offer of US$300 million was made 1898 just

before the outbreak of the Spanish-American war, but could not be accepted by Spain

(Thomas 1971, p367). Aside from purchase, another American option that was often

mooted was outright annexation of the island, a move that gained force in southern

U.S. states after 1845. Both of these trends were supported by the idea of a wider

'manifest destiny' for the United States as an advanced nation based on a superior

Anglo-Saxon tradition which had a responsibility to use its greatness (Chiodo; 2000;

Thomas 1971, pp210-212). Indeed, during the late 19th century, possession, or at

least control, of Cuba, became 'a fixed ambition of U.S. foreign policy' (Perez

1998).

Others, more impatient, sought an unofficial and more direct solution to securing

Cuba. The rebel Narciso López would find backers in the southern U.S. and launch

several attempted invasions of the island, culminating in his death in 1850 (Thomas

1971, p217). History, as we shall see, would repeat itself. López however, did leave

one lasting legacy to Cuba: 'the Cuban flag from the day of independence in 1902 to

the present day is one designed by López', reflecting both the flag of Texas and of the

Union (Thomas 1971, p217). The hope of some Americans and Cubans had been that

Cuba would declare itself independent, and then join the U.S. as a 'southern' state

supporting slavery (Thomas 1971, p220).

The Flag of the Republic of Cuban

Cubans also formed strong lobby groups in New York and Washington, while a

community of over 18,000 had established themselves in Key West in Florida by

1870 (Thomas 1971, p291). Today this expatriate community, many of them

fiercely opposed to Castro, comprise a large and influential lobby within the

population of Florida (see further below). In the long run it is not surprising that the

U.S. and Cuba have been deeply involved with each other.

4. The Revolutionary Legacy of the 19th Century

The revolutionary traditions of Cuba were played out against the great revolts by

many Spanish American territories which from 1810 began to try to assert their

independence, e.g. Mexico. The first movement for outright independence in Cuba

began in 1809 and led by Román de la Luz, but the attempt was soon broken

(Thomas 1971, pp88-89). The movement gained strength around 1823, this time lead

by mason groups, often appealing to students and 'poorer white Cubans', who were

Lecture 4

6

urged to united with free and slave blacks (Thomas 1971, p101). The movement was

crushed, aided by large numbers of Spanish troops, resulting in martial law that

effectively last some fifty years (Thomas 1971, p103). Likewise, President Lincoln's

proclamation against slavery in the U.S. of 1863 caused great enthusiasm among

blacks in Cuba (Thomas 1971, p235). It was in the 19th century that the first organised

strikes in Cuba occurred and in the 1850s many workers began to create mutual aid

societies (Thomas 1971, p236). In the long run, revolutionary ideas of anarchosyndicalist thought, deriving from Bakunin and Fanelli, would being to influence

Cuba and its labour movements, especially through activists such as Enrique Roig

(Thomas 1971, p249, p291).

Other reformers included Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, who was active from the

1850s and very critical of Spanish policies (Thomas 1971, p243). In 1868 this man led

reformist planters in the east of the island against Spanish rule: his program included

the gradual emancipation of all slaves (Thomas 1971, p245). He quickly mustered an

army of some 12,000 men and launched the war of 1868-1878. Later 'liberators' in the

war would include Antonio Maceo, Calixto Garcia, and later on Máximo Gómez. This

conflict tended to focus on the poorer eastern part of the island, and only after 1875

would carry on raids into the richer plantations of the western section of Cuba

(Thomas 1971, p264). Up to 258,000 - 300,000 (10% of the total population) may

have died during the conflict (Thomas 1971, p269, p423), in large part due to disease

and localised famines as much as from direct warfare. In the end, massive Spanish

military reinforcement and divisions within the rebel camp would lead to the failure of

the rebellion. However, after the war there was some limited move towards

democracy: based on property qualifications, all Cuban were allowed to vote for

municipal and local councils (Thomas 1971, pp267-268). The conflict also inspired

strong support for the freeing of slaves, and laid the basis of the a 'strong nationalist

spirit' in Cuba that has never died out (Thomas 1971, p270). The tradition of Carlos

Manuel de Céspedes and other revolutionary leaders such as Máximo Gómez and

Antonio Maceo helped establish the tradition of heroic Cuban patriotism (Williamson

1992, p437) that would be mobilised in the following century.

Another strong influence on this tradition was the brilliant José Martí (1853-1895),

who remains popular today, in part because of his staunch opposition to the idea of

annexation by the U.S. (Thomas 1971, pp295-298). Operating from the U.S., Martí

founded revolutionary schools and in 1892 formed the Cuban Revolutionary Party

and along with other leaders, especially Máximo Gómez helped launch a rather

premature War of Independence in 1895 (Thomas 1971, pp306-316). Martí was

himself killed in 1895, but left an enduring legacy. The result was a sustained

revolution (see Williford 1998) using the methods of guerrilla warfare that created a

fierce debate internationally, including a major contest for newspaper coverage in the

U.S., with a section of the American press supporting the idea of a free Cuba (Perez

1998). José Martí himself came to be viewed as one of the founders of modern

Cuba, in part through his creation of the Partido Revolucionario Cubano (PRC) and

in part because of his voluminous writings. He was one of the strongest explicit

inspirations for Castro (Quirk 1993, p53).

In this context, national identity (Cubanidad) and nationalism began to draw on

these revolutionary legacies. Building on the 19th century revolutionary movement,

Lecture 4

7

the 1959 revolution also promoted a specific sense of national identity through

cultural forms, including music, art and, for a time, architecture: Cubanidad, or the nature of Cuban identity, is a debate that had been taking place

since the 19th century. Jose Marti, who is upheld as the original and most important

intellectual figure in the long-running struggle for Cuban independence, understood

the need to establish a specific culture, free from traditional Spanish domination, that

recognized the fusion of both African and Spanish influences on an equal basis.

Although the development of Cubanidad remained centrally important for the

relatively small intellectual community throughout the first half of the 20 th century, its

influence was subsumed by the continued spread of Western capitalism. It was only

the 1959 revolution that provided the unique opportunity to promote an architecture

that truly reflected Cubanidad. (Foster 1999)

During 1897, the revolution against Spain led to American fears for their economic

and strategic interests in Cuba, and the battleship Maine was dispatched to Havana

to protect U.S. concerns (for the complexity of U.S. public opinion, see Perez 1998).

Unfortunately, the battleship Maine blew up in the Havana harbour on 15 February

1898, with some 260 deaths (Thomas 1971, p361). The cause for the explosion was

never securely identified, whether due to sabotage, an uncharted mine, or an

accidental explosion due to the new gun-powder mixture that was being issued to

American ships. Regardless of the exact causes, the result was a wave of hysteria in

the U.S. against Spain (see Detemple 2001), a wave that pushed ahead the plans of

Roosevelt and others to take control of Cuba, the Philippines and Guam (Thomas

1971, p364-365). In spite of attempted negotiation and the offer of recompense from

Spain, President McKinley and the U.S. Congress declared war on Spain on 25

April 1898, but without recognising the rebel Cuban government (Thomas 1971,

pp376-380). In effect, the U.S. no longer trusted that Spain could keep control of the

island, nor was it willing to recognise the revolutionary forces of Cuba, which were

poised for victory in the field (Perez 1998). In effect, its intervention was against both

the Spanish and Cuban forces.

The Spanish navy, small and old fashioned, had no chance against the modern U.S.

fleet. The outcome of this war was wider than just its impact on Cuba. It led to the

U.S. occupation of the Philippines (where the independence claims of General

Aguinaldo were not accepted) and Guam, control of Puerto Rico, and military

administration of Cuba from 1899-1902. Thereafter, for several decades, the U.S. had

a privileged position with regard to Cuba, where they could intervene either if U.S.

'interests' were at risk, or if any other power seemed to be gaining influence on the

island (Thomas 1971, p402, pp450-454). This was done through the 'Platt

Amendment', which gave the U.S. the right to intervene on almost any pretext if U.S.

interests or the stability of the Cuban government was not assured - the policy was

only reluctantly accepted by the Cuban Constituent Assembly in June 1901 (August

1999, p103). Cuban sovereignty was controlled and limited by U.S. interests (Perez

1998). It also made the career of Theodore Roosevelt, who as a Colonel of the

Roughriders led his famous charge up San Juan Hill (in Cuba). Thereafter, Roosevelt

became governor of New York State and then President. He continued a policy of

unique influence for the U.S. throughout South and Central America. A combination

of indigenous revolution and U.S. intervention had ended Spain's control of

Cuba.

Lecture 4

8

During the 19th century the movement towards independence was augmented first by

the failure of the U.S. to annex the island, and then by the way early 20th century U.S.

interests which developed the island as a 'sugar factory' and strategic naval base

(Thomas 1971, p227). On the 20th of May 1902 Cuba achieved formal

independence under its first President, Estrada Palma, but this would not be the

beginning of a smooth ride for the new nation. Political turmoil continued. Between

1906 and 1909 Cuba was ruled directly by the U.S., while between 1909 and 1921

American troops were sent to intervene in the politics of the island on four occasions

(Williamson 1992, p440).

From 1902-1959 the history of Cuba reads as a long serious of partially corrupt

elections, U.S. interventions in Cuban government (as in 1906-1909), the emergence

of strong labour and socialist or communist parties through the 1920s and 1930s, and

a growing social crisis that could not be averted even by electoral politics. The

Partido Communista de Cuba (PCC) was formed in 1925, at first under the leadership

of Julio Antonio Mella (August 1999, p121). Political violence continued in 19261927, and although the U.S. managed to helped remove the dictator Machado in 1933

through political pressure, a reformist government in 1933 under Carlos Céspedes

could not be sustained (Gilcrease & Dur 2002;Williamson 1992, pp441-442).

Essentially, the period from 1902-1959 saw unstable variants of electoral multi-party

politics in which Liberals verses Conservatives were unable to either provide stable

government or set in train a successful period of economic and social reform (see

August 1999). It was also a period in which U.S. interests politically and

economically remained extremely strong in the island (O'Brien 1993; Nackerud et al

1999). Part of this presence included a strong infiltration of the U.S. mafia in the

island from 1934-1958, with key figures such as Lucky Luciano and Meyer Lansky

operating out of their own hotels on the island (August 1999, p137).

In 1952 Fulgencio Batista organised a coup d'état and took direct control of the state

(August 1999, p140), no longer remaining as a strongman behind the scenes.

Thereafter Batista arrested or harassed opposition groups, as in the 1954 general

elections (Qirk 1993, p79). The Batista government emerged as a military dictatorship

which sought to oppress all serious opposition and coopt most senators, the police,

and the armed forces (Mericle 1998; Quirk 1993, p38). This government also received

military aid from the U.S. through the Mutual Defense Assistance Agreement. The

U.S. supported this government essentially in order to retain its privileged influence in

the Caribbean, to protect financial investments, and in order to keep communist and

socialist forces in check on the island. Batista's Cuba had 60% of its exports and 80%

of its imports from the U.S. (Nackerud et al. 1999). Appeals to the Organisation of

American States to restore 'legitimate rule' in Cuba were unsuccessful (Quirk 1993,

p39). It was this regime and its harshness that set the stage for a new and eventually

successful revolution.

5. Castro's Revolution

Fidel Castro was one of several young revolutionaries that returned to Cuba in 1956,

and began the formation of a Rebel Army and military operations on the island. A

young lawyer, he turned from political activity on the fringes of the existing Ortodoxo

Lecture 4

9

party towards direct action against the Batista regime (Quirk 1993, pp31-50). Among

those who joined him was Che (Ernesto) Guevara, whose revolutionary gusto and

courage soon gained him a command position. Che would later on try to bring

revolution into South American and would eventually be killed by the Bolivian army

in 1967 (Dorfman 1999). A range of other guerrilla leaders, e.g. Frank País and René

Ramos Latour, would not retain such prominence, nor Castro's favour (Qirk 1993,

pp141-148). This guerrilla war, led from the mountains of the Sierra Maestra,

combined urban resistance and destabilisation campaigns in the countryside

(Williamson 1992, p445; Quirk 1993, p130), culminating in a general insurrection and

the crumpling of the Batista government through 1958-1959. The brutality of the

Batista regime had alienated many Cubans and the Catholic Church (see Super 2003),

while allowing elements in the international media to be sympathetic to Castro's

'heroic' struggle in the mountains, e.g. coverage by the New York Times, the Chicago

Sun-Times and Paris-Match (Williamson 1992, p446; Quirk 1993, pp131-136). It was

in such media coverage the Castro developed the persona of the bearded, riflecarrying guerilla operating at will from mountain strongholds (Quirk 1993, p134).

When the will of Batista's army collapsed, the dictator and some of his followers flew

out of the island. By January 1959 revolutionary forces had secured Cuba. At first

Manuel Urrutia was sworn in as provisional president (Quirk 1993, p216), but it soon

emerged that Fidel Castro and his inner circle of revolutionary leaders directly

controlled Cuba's future (Castro was at first Premier, and later became President).

Fidel Castro himself had earlier on been captured during a 26 July 1953 attack on the

Moncada barracks (see Hickson 1996). His most famous exposition of revolutionary

ideology was made in his two hour defence speech before a closed hearing, called

History Will Absolve Me, and sometimes known as the July 26 Program (August

1999, pp151-153; Castro 1968). Although not yet overtly communist (Fidel was

himself at first a member of the Partido del Pueblo Cuban - Ortodoxo, a progressive

party), it outlined a plan of national liberation based on armed struggle and the

aim of transforming society towards a more just system (August 1999, pp153156). Something of the tone of History Will Absolve Me can be seen in the following:

When we speak of struggle, the people means the vast unredeemed masses, to

whom all make promise and whom all deceive; we mean the people who yearn for a

better, more dignified and more just nation; who are moved by ancestral aspirations

of justice, for they have suffered injustice and mockery, generation after generation;

who long for great and wise changes in all aspects of their life; people, who, to attain

these changes, are ready to give even the very last breath of their lives - when they

believe in something or in someone, especially when they believe in themselves . . .

(in August 1999, p159)

Other aspects of this platform included 'industrialization, redistribution of land, full

employment, and the modernization of education' (Williamson 1992, p445). These

views were further refined during a period in prison and then in exile from 1955

(Quirk 1993, pp57-59, pp85-86). At first, his program might be viewed as more

'utopian than Marxist' (Quirk 1993, p160), but soon drew on a range of utopian and

socialist ideas.

Views on Castro's Cuba tend to be polarised both by political ideology and by

propaganda (those for and those against Castro). Strong anti-Castro lobbies exist in

Lecture 4

10

the U.S., at first mobilised through groups such as the Democratic Revolutionary

Front (DRF) and the Movement for Revolutionary Recovery (MRR) which were

active from 1960 onwards (MacGaffey & Barnett 1962, pp264-265). Even by

December 1960 there were 30,000 Cuban refugees in Florida (MacGaffey & Barnett

1962, p273). More recently, the Cuban American Foundation (CANF) has been quite

influential in lobbying and influencing American foreign policy (Vanderbush &

Haney 1999). Today, a very vocal Cuban emigre lobby still remains highly effective

in the U.S., but middle-of-the-road Cuban groups, though critical of Cuba, have tried

to present more moderate views (Lantigua 2000). The point is that statements about

Cuba (from both sides) need to looked at closely and critically.

The Castro government sought from the very beginning to link themselves to

revolutionary tradition of the island: The regime sought to consolidate popular support behind it by identifying the

revolution of 1959 as closely as possible with the nineteenth-century nationalist

movement. The Cuban people consider the decades immediately preceding the

winning of their independence from Spain as the most glorious in their history and

regard the philosophers and patriot-heroes of this period as the noblest men the

country has produced. Revolutionary spokesmen therefore depicted their program of

economic and social reform as the culmination of an idealistic tradition which dates

back to José Martí and the War of Independence. Premier Castro himself regularly

and freely drew on Martí's writings for his public addresses and, when he posed for

photographs, there was often a picture or statue of Martí somewhere in the

background (MacGaffey & Barnett 1962, p271).

Castro's and Che's ideas were at first not directly derived from Soviet thought. Rather,

they combined socialist and utopian elements already developed in the Hispanic

tradition. They aimed not just at a national and social revolution, but also spoke of a

'New Man' free from greed and personal ambition who would be the basis of a

sharing and just society (Williamson 1992, p447).

The policies of the Cuban government included the creation of a single-party state

(based on the merger of several revolutionary parties including the communist,

student, and socialist groups), the development of mass-housing projects to provide

every Cuban with the ability to have their own home, the extension of the health and

education system, and the creation of a nationalised economy in which 80% of

labour would be employed directly or indirectly by the government, and retain state

control of all major publishing, media and film production units (MacGaffey &

Barnett 1962, pp275-278; August 1999, p161). Among the first actions of the Castro

government was the nationalisation of most industry and expropriation of 41% of

land which was divided up and given to peasants (August 1999, p174). They also

promoted the creation of a new news agency for South America, Prensa Latina,

which claimed to provide an independent new service free from 'imperialist'

domination, while suppressing several critical newspapers and magazines (MacGaffey

& Barnett 1962, p279).

Fidel Castro also soon began to create a cult of personal leadership, in part based on

his vigorous speeches and embodiment of revolutionary ideals, e.g. his continued

public appearances in military fatigues and his avoidance of personal luxury. He came

to be regarded 'as a patron, guardian, and guarantor of salvation in a sense that had

both religious and secular overtones' (MacGaffey & Barnett 1962, p285). In a very

Lecture 4

11

real sense, Fidel based his legitimation on cultural and nationalistic grounds as

much as on a platform of left-wing social reform. In following years a strong

personality cult developed around Castro as 'the Maximum Leader' (Quirk 1993,

p255).

The revolution had a serious impact on Latin American politics generally: For the Cuban revolution discredited the cautious reformism of the communist parties,

identifying socialism with long-standing Latin American traditions of armed rebellion. It

also held out the hope of realizing the highest aspirations of nationalism: the forging

of an authentic cultural identity once foreign imperialists and their agents had been

driven out of the country. The Cuban guerrilla struggle was to provide a pattern for

other wars of liberation in the continent, as well as in Africa and Asia. (Williamson

1992, p354)

Originally, the foreign policy of Castro's Cuba was based on good relations with all

American states: hence his government was initially cautiously recognised by the U.S.

and by all Latin American countries (MacGaffey & Barnett 1962, p312). Relations

soon worsened, in part due to the nationalisation of American companies, the U.S.

welcoming of political refugees, and the U.S. fear of communist influence in Cuba.

By January 1961, Cuba and the U.S. had broken off diplomatic relations (MacGaffey

& Barnett 1962, pp320-328). The strongly socialist and nationalising policies of

Castro worried the U.S., and when Castro described his country as Socialist in a

speech of May 1, 1961, this presaged a move towards alignment with the Soviet

Union and the Comecon (socialist) countries (Quirk 1993, p385). In part, this

alignment was based on a need to assure technology, trade and access to petroleum for

Cuba. Through 1960-1961, this also included a conventional arms build up, the arrival

of MiG fighter aircraft, and training from Soviet and Czechoslovakian sources (Hatch

& Johnson 1998). In 1965 a new Cuban Communist Party was formed

(Williamson 1992, p454), also indicating further alignment.

6. Conflict and Containment

The U.S. government soon moved against Castro's government, in part based on

conflicts over 'intervened' and the seized resources of many U.S. companies

(including nationalisation of Esso and Shell holdings on the island), but more

importantly on Cuba's drift towards alignment with the Soviet Union (Quirk 1993,

p283, p319, p348). Dwight Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy established the

economic and trade embargo on Cuba. The embargo restricted ships which had

been to Cuba from visiting the U.S., banned exports and imports, stopped the trade in

food and medicines. At its peak: 1) froze all Cuban bank accounts in the United States; 2) prohibited U.S. citizens from

sending money to Cuba, spending money in Cuba, or doing business with any Cuban

form in foreign countries; 3) banned U.S. trade with any country that contained Cuban

components; 4) forbade U.S. companies abroad from doing business with Cuba; 5)

refused to allow international financial institutions to issue credit to Cuba; and 6)

prohibited foreign nations from using U.S. dollars with Cuba (Nackerud et al. 1999).

American containment continued with the effort to overthrow Castro's government

through the backing of emigre groups in the U.S. who formed an army and invaded

the island. From 1960 through 1961 military equipment and training camps were

Lecture 4

12

provided for them in Florida, Louisiana and Guatemala, including the training of

pilots in a small number of old B-26 bomber aircraft (MacGaffey & Barnett 1962,

pp266-267; Quirk 1993, p367). The main planning and liaison for the operation was

the CIA, with the U.S. government in general (and President Kennedy in particular)

thereby hoping to plausibly deny that it had staged the invasion of another country.

An invasion force of 1,500 men landed at the Bahía des Cochinos (Bay of Pigs) on

April 17, 1961 but were unable to leave the beachhead they had established

(MacGaffey & Barnett 1962, p268). Planning for the operation had disastrously

underestimated the effectiveness of the Cuban army and Castro's intelligence

networks (see Kornbluh 1998). Within days Castro had captured most of the invasion

force (1,189 of 1,500 troops), and made a formal complaint to the Security Council of

the U.N. that this was a mercenary force in the employ of the U.S. (MacGaffey &

Barnett 1962, p329; Quirk 1993, p374). The result was extreme embarrassment for the

Kennedy administration, but worse was to follow.

The Cuban missile crisis had its roots in superpower competition and Castro's need

to secure the island against future U.S. military intervention. The Soviet leader Nikita

Krushchev, in particular, was willing to test the abilities of the new American

President Kennedy, and to try to gain strategic leverage in the Americas. In part, he

hoped to use this pressure to push or leverage the Western powers out of West Berlin

(Quirk 1993, pp408-416). In doing so, he directly challenged the balance of power

between the superpowers, and also began to undermine the Monroe doctrine whereby

the U.S. would resist outside influences in the Americas. To achieve these goals he

began the positioning of medium range nuclear-capable ballistic missiles (SS-4s) in

Cuba (Hatch & Johnson 1998). In fact, the initiative for locating the missiles just off

the coast of the U.S. came from Russia, not from Cuba, and it now seems likely that

Krushchev hoped to trade the removal of the missiles in Cuba for a pledge by the U.S.

not to position nuclear weapons in West Germany (Ulam 1998).

On this basis, President Kennedy decided to impose a blockade (naval quarantine)

of the island, and mobilised U.S. forces to a higher level of readiness. Crisis

diplomacy followed, with the dispute being at last resolved with a series of personal

communications between the two leaders. Soviet ships turned back before a direct

confrontation at sea could occur. Soviet missiles were withdrawn from Cuba, but in

return U.S. medium range Jupiter missiles were withdrawn from Turkey and the U.S.

administration undertook not to invade Cuba (Ulam 1998; Quirk 1993, p429). A

directly military confrontation had been avoided, but only just (see Chang et al. 1998).

The outcome for Cuba, however, was a long-term Soviet alignment. Cuba was now

firmly entrenched in the Socialist community of nations, and supported by

preferential trading arrangements and the supply of subsidised oil from the Soviet

Union. Cuba sold sugar at good rates to the Soviets, and received petroleum,

machinery, iron, steel, aluminium, armaments and technical assistance (Quirk 1993,

p295). In 1989, '80% of Cuba's total trade was with socialist economies' (Monreal &

Hammond 1999). Cuba also for a time continued an active policy of supporting

revolutionary movements in South America and Africa, e.g. involvement in the

Congo, Angola, Bolivia (where Che Guevara was killed in 1967), Ethiopia, as well as

sending advisers and workers sent to Jamaica and Grenada (Williamson 1992, p455).

Lecture 4

13

However, in turn, Cuba to was subject to a continued U.S. embargo, which would

begin to seriously undermine the Cuban economy from 1990 onwards.

After 1989 the USSR began to adjust its international policies, including some

reduction in aid to socialist countries around the world, and eventual demands for

hard currency payments for oil and armaments. From 1992, with the collapse of the

Soviet Union and the greatly weakened position of the Russian economy, this led to

the loss of the $5 billion annual Soviet subsidy that had helped keep the Cuban

economy viable (Robinson 2000, p116; Nackerud et al. 1999 argues that the subsidy

may have been as high as $8 billion). After an initial 35% reduction in the economy in

the 1993 in Cuba (Monreal & Hammond 1999), growth returned during 1995-1999,

with 6% growth achieved in 1999 (Robinson 2000, p116). This growth was achieved

in part of emphasising trade with countries such as China, but also by a new emphasis

on connections with Europe, emphasis on tourism, and some diversification within the

Cuban economy, allowing a larger private sector (see below). Through the transition

period of 1994-2001 average GDP growth was approximately 4%, but from a

relatively low baseline (see Brundenius 2002). Growth in 2002 was only 1.1%, but

increased to 2.6 through 2003 (NotiCen 2004), with real GDP growth of 3% in 2004

(according to the Economist Intelligence Unit, 5% says the Cuban government,

Economist 2005a). The Cuban government claims 11.8% growth for 2005 (Prensa

Latina 2006b).

With the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War this was not the

signal for the softening of U.S. pressure on Cuba. On the contrary, U.S. pressure

intensified, especially over the issue of lack of a multi-party democracy within Cuba

(August 1999, p19). This can be seen in a range of U.S. legislation designed to

increase economic pressure on Cuba (August 1999, p19), and on countries or business

dealing with Cuba. This legislation included the Cuban Democracy Act of 1992 (the

Torricelli Act, tightening the embargo), and the Cuban Liberty and Democratic

Solidarity Act of 1996 (the Helms-Burton legislation, designed to reduce investment

and aid from other countries). The U.N. has regularly protested again the blockade,

while no other government has agreed to support the embargo to the degree outlined

in the Cuban Democracy Act (Nackerud et al. 1999).

One of the triggers for the support given the Helms-Burton legislation was the

shooting down on 24 February 1996 of two civilian aircraft, piloted by a CubanAmerican exile group (Brothers to the Rescue), by Cuban MiGs and involving the

death of four people (Vanderbush & Haney 1999). The Helms-Burton provisions

include a unilateral policy to prosecute foreign companies and individuals that deal

with Cuba beyond specified levels - a move which the European Union said could

draw counter-measures against American companies if it were ever applied (Tremlett

1998). The use of this internationally unpopular provision was eventually waved by

former President Clinton (Nackerud et al. 1999). An important part of the HelmsBurton law (called Title II) sets out a 'list of conditions that any post-Castro

government must meet in order to resume normal relations with the United States, to

receive diplomatic recognition, seek aid and trait' (Robinson 2000, pp128-129). This

list is highly reminiscent of the earlier Platt Amendment (Robinson 2000, p129), in

which the U.S. tried to dictate terms to Cuba for some 50 years. Most aspects of the

Helms-Burton legislation has been codified into law, meaning that it cannot be

repealed by the President alone, but will need the support of Congress if there is to be

Lecture 4

14

any complete lifting of the embargo on Cuba (Vanderbush & Haney 1999). This

approach does not bode well for future relations, even if the Castro regime falls.

Furthermore, even if the embargo is lifted, there are some $6 billion in U.S. claims

against Cuba's earlier confiscations of property, while Cuba in turn claims that it

should receive $80 billion in compensation for the damage done by the forty years of

embargo (Falcoff 2000). There was some slight softening in the U.S. government

policies against Cuba through 2001-2002, but this has been complicated by the

heightened security needs of the U.S., as well as by some concern that Cuba might

still be directly or indirectly supporting terrorist or guerrilla groups, as well as

possible contacts with the IRA and FARC in Colombia, charges denied by Cuba (for

the Cuban view, see Hernandez 2002).

Ironically, this increased U.S. pressure may have strengthened the Castro regime,

as noted by Linda Robinson: US pressure gave Castro an excuse to strengthen his internal position, a rationale for

his refusal to change and a rallying point to demand greater sacrifices from the

population. An enemy abroad is always a useful ally during times of trouble at home.

Furthermore US policy-makers were unable to deny Cuba the alternative sources of

external support that it sought to cultivate. And, finally, US immigration policy

continued to aid Castro by providing him with an escape valve for internal discontent

that he may not have otherwise been able to manage. (Robinson 2000, 117).

It is interesting to compare the hard line taken with Cuba in comparison to the fact

that the US has normalised relations with Vietnam (Robinson 2000, p118) and China.

Many Americans are beginning to wonder whether the embargo is effective. In a

general 1999 Gallup pole some 71% of Americans thought it was time to renew

diplomatic relations and 51% to raise the embargo (Robinson 2000, p118). The

maintenance of the this hardline U.S. policy in part may be due to a traditional effort

to keep control of Central American affairs, to a frozen foreign policy in Washington

on this issue since 1962, and due to an emigre Cuban anti-Castro lobby that has been

especially active in Florida. Likewise, some business and agricultural groups are keen

to see an easing of restrictions on trade with Cuba.

7. The Case of Elian Gonzalez

The bizarre case of this 6-year old boy which hit the headlines during 1999-2000

helps highlight the strange relationship that exists between the U.S. and Cuba. Elian

Gonzalez and his mother were among a group of refugees that tried to make the

crossing to the U.S. Their boat sank and the mother drowned, but on the 25th of

November 1999 Elian was found clinging to an inner tube off the coast of Florida. He

was saved and found himself temporarily in the U.S. in the care of his great-uncle. At

that point, the relatives of Elian wanted him to receive asylum and stay in the U.S.

However, the father of Elian was still alive in Cuba, and demanded the boy's return.

President Castro vowed to ensure the boy would return, while the U.S. Immigration

and Naturalisation Service decreed that only the father could represent the boy

(Romei 2000). This led to a major series of court cases and public protests in both the

U.S. and Cuba. Efforts by the boy's Miami relatives to have courts mandate asylum

for the boy ultimately failed after several months of highly public activity, and the boy

and his father eventually returned to Cuba at the end of June, 2000.

Lecture 4

15

The incident sparked off deep emotions in both Cuba and Florida. Within Cuba,

millions of people marched in December 1999-January 2000 in support of the return

of he boy, a protest that was not entirely orchestrated by the Cuban government

(Robinson 2000, p126), but which was used by Castro as part of his sustained antiAmerican rhetoric (Tamayo 2000). The case seemed in microcosm to demonstrate

extremism on both sides, and in the long run showed the vitriolic nature of the antiCastro lobby on Florida as well as the political opportunism of Castro. The boy was

eventually returned to his father, and then to Cuba in early July in conformity with the

laws of the U.S. and with international law (Economist 2000). Overall, the case was

something of a victory for those who wished to soften the embargo against Cuba

(Tamayo 2000). Indeed, by late June 2000 moves were initiated to try to lift the

embargo on food and medicine going to Cuba, a policy supported by the Senate

Foreign Relations Committee (Brasher 2000). However, one cannot help but wonder

about the long term psychological damage to a young boy who was on national

television the day after his mother had died and he had been plucked from the sea

(Morris 2000). In the long term, such events suggested that both U.S. and Cuban

policies were playing out the legacies of the Cold War, in part directed to domestic

audiences.

8. Modern Cuba: A Unique Culture Playing A Unique Strategy

It is not enough to simply dismiss the Cuban political system as an outdated

communist regime. On the contrary, the Cuban system represents a complex mix of

South and Central American political legacies, as well as socialist, cultural and

nationalistic factors that has helped the regime to survive for four decades in the face

of sustained U.S. opposition. Thus, in the Declaration of Santiago, made in the 1959

meeting of the Organisation of American States in Chile, Cuba among other states,

had affirmed the 'seven principles regarding human rights, including the separation of

powers, free elections, equality before the law, and freedom of the press and radio',

though external invention to enforce these principles was not regarded as acceptable

(MacGaffey & Barnett 1962, p330). However, by 1961 the United States had brought

charges against Cuba in the OAS, arguing that it was destroying the inter-American

system by aligning with the Soviets, with Cuba thereafter being effectively excluded

from voting in the organisation (Quirk 1993, p397, p400).

Since that time, fierce debate has raged between Cuba supporters and opponents

(especially among the Cuban exiles in America) as to whether the Cuban government

is legitimate. In particular, however, it must be remembered that the current Cuban

regime has never supported a multi-party system, in part because of the way the

traditional party system was manipulated by elite and U.S. interests through 19021958 (August 1999, p166). Thus Cuba did run relatively free municipal elections in

1997-1998, allowing a range of candidates, but opposition parties were not allowed.

Likewise, there has been a partly circumscribed and limited space for religious

and civil organisations, though a vigorous network of clubs and societies has

proliferated, often oriented around government agenda, e.g. in music, sport, and

education (see below).

There were some real achievements to the revolution: improved literacy, improved

food supply for the poor, provision of housing and education, an effective health-care

system, and efforts to reduce race and gender prejudices (Williamson 1992, p452).

Lecture 4

16

Cuba certainly tried to create a strong welfare and educational system, with the

result that, in spite of the U.S. embargo, the medical system of the country has been

quite strong. Thus Cuba in 1998 received the Health for All Medal from the WHO

(August 1999, pp23-24). Likewise, Cuban doctors developed a meningitis B vaccine

in 1998, which American companies wish to access, a move which Castro supports on

humanitarian grounds (Tremlett 1998). Thereafter, Cuba traded its medical

expertise, services and medicines to Venezuela (in return for oil) and to Argentina

(reducing Cuba's 1.9 billion in debt) in 'swap' deals: '15,000 Cuban doctors and nurses

and a similar number of teachers, sports trainers and other advisers are working in

Venezuela' (Economist 2005a; Rogers 2003). Cuban doctors have also been active in

Zimbabwe, Zambia, Mozambique, South Africa, Malawi, Angola, Botswana, Chad,

Lesotho and Tanzania (Africa News Service 2004).

The Cuban view of democracy includes an emphasis on the right to economic and

sustainable development, a view put forward that the Margarita Summit of

American States in 1997 held in Chile (August 1999, pp21-23, p26). Although Cuba

remains an active participant of the Ibero-American Summits, one of the few

international forums open to it (Cuba had been suspended from the Organization of

American States in 1962). This forum re-iterated its stance against the embargo

through 2005:

The US blockade against Cuba suffered unanimous opprobrium at the XV Cumbre

Iberoamericana in Salamanca, Spain, which ended Oct. 15. All 22 member states of

the regional community signed on to a Special Declaration calling for an end to the

economic, financial, and trade sanctions the US has imposed on the island for the

past 40 years. The declaration also demands that the US suspend all laws contrary to

international law, including the Helms-Burton Act . . . and rescind all measures

adopted in the last two years strengthening the impact of the blockade. (NotiCen

2005a)

However, not all member states accepted Cuba's claims to having a legitimate

political system. Strongest critics in the past included 'Argentine President Carlos

Menem and Nicaragua's leader Arnoldo Aleman, known for his fierce anti-communist

stance.' (CNN Interactive 1997) Perhaps 'the greatest achievement was the forging of

a common national spirit, something that most other Latin American republics had

failed to do' (Williamson 1992, p457). In general terms, over the last decade there has

been some improvement in Cuban relations regionally, e.g. with Brazil, Mexico,

Venezuela, and Canada.

At the same time, Cuba has kept extremely tight control on political opposition,

has limited freedom of speech in political matters, and has developed a security

mentality that has led to constant U.S. and more recently UN charges of human rights

abuses (see the annual U.S. Department of State Country Reports for Cuba). Some

commentators such as Arnold August have suggested that lively political debate does

exist in Cuba, indicating some degree of political pluralism (August 1999, p24).

Certainly since 1989 there was some improvement in Cuba's human rights record

(Nackerud et al. 1999), though crackdowns occurred again through 2003 (Bond

2003). There has been an increase in the number of NGOs and relatively

independent organisations on the island. By 1995 some 2,200 NGO's had been

registered with the Cuban government, though it is true that only some of these are

genuinely independent organisations (Gunn 1995). Among these is the Asociación

Lecture 4

17

Cultural Yoruba de Cuba and the Pablo Milanés Foundation, formed in 1990 by a

black singer and aimed at supporting young Cuban musicians and other independent

cultural activities, especially those focusing on Afro-Cuban culture (Gunn 1995). The

Yoruba Cultural Association's registration is significant, since although Yoruba

ceremonies had been legalised by Castro in 1959, the cult itself was strongly

discouraged and viewed by the Cuban Communist Party as a superstitious practice

that should be left behind (Gunn 1995). The Confradía de la Negritud (Black

Brotherhood) has been formed to fight racism (de la Fuente 2001, p34), while other

organisations focus on human rights or religious activities. It useful to distinguish in

Cuba among congos (controlled government organisations), gongos

('government-oriented non-government' organisations), and more autonomous

NGOs in the definitional sense (Fernández 2000, p133), with Cuba currently

demonstrating a wide spectrum of top-down and bottom-up forms of organisation.

The role of many of these organisations has been to draw in social support locally, as

well as to provide information channels for government policy and build international

linkages. Artists, writers (via the National Union of Cuban Writers and Artists

(UNEAC), and musicians have increasingly been forum for debate on social issues,

though from 1996 the Cuban government has slowed the creation of truly

independent NGOs (see Dilla Alfonso 2006). A wide range of Unions and other

associations have some level of partial autonomy, but only within the wider values of

the Cuban revolution: . . . sessions with representatives from the Cuban Women's Federation and a

combined group from the Communist Youth League and the University Students'

Federation, including the Women's group This major mass organization was set up in

1960 at all levels and advises the government on policy, actively seeks increased

participation of women and represents Cuba internationally in women’s forums. 27%

of MP's are women: 66% of the technical and professional workforce and 33% of

decision makers. However women are still mainly employed in education and health

but this is changing with more women than men now in higher education. Successes

achieved include a reduction in domestic violence; non-sexist education; a major

improvement in women's health; generous maternity leave; day care for workers'

children; the rehabilitation of prostitutes; and a life expectancy for women of 78.

(Meggitt 2003)

There are real limits on how far these debates can go in criticising the government,

and official organisation of opposing political parties has not been tolerated. Political

and individual liberties remain strongly limited, and the government moved to

tighten political control through 2001-2003 (Aguirre 2002; Nackerud et al. 1999).

These factors led to the decision of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights

(UNCHR) to pass in April 2000 a resolution criticising Cuba's performance in the

human rights area. The resolution, sponsored by Poland and the Czech Republic, was

passed by 21 to 18, with 14 abstentions. In May 2001, some 40 independent

journalists operating in Cuba have asked to be allowed to legally form an independent

journalists association, pledging that they will not accept money from any

government, including the U.S., indicating efforts at more open public dialogue

(Sequera 2001). The criticisms by the UN Human Commission on Human Rights

were re-iterated through 2004, in part responding to a crack down on dissidents

through 2003, a policy also support by the EU and Spain until early 2005.

Recent efforts to open up more civil liberties on the island have included the

Varela Project (asking for a referendum on democratic reforms, a program led by

Lecture 4

18

overseas dissidents such as Oswaldo Paya), and the Assembly to Promote Civil

Society in Cuba (San Martin & Rayes 2002; Agence France Press 2003). This forms

at best a fragmented agenda for reform in Cuba: Another distinct actor is the group of organizations espousing diverse creeds, issues,

and positions that comprises the opposition to the Cuban political regime and, in

contrast to the antiestablishment groups of the 1960s, is characterized by its

nonviolent positions. This actor is also extremely fragmented, heavily infiltrated by the

Cuban state security apparatus and has an international profile that far surpasses its

political influence inside the country.

The organized opposition has achieved indisputable successes including the

formation of coalitions and public support in the form of 25,000 signatures for the

Varela Project, a petition calling for legal reforms. Nonetheless, it has been incapable

of channeling the growing discontent among Cubans. . . .

The Cuban government, for its part, asserts that these groups lack legitimacy

because of their international links with countries and organizations hostile not only to

the Cuban government, but to the historic process of revolutionary change. And while

that argument could be reasonably applied to some of these groups, it hardly explains

the repression of other groups and individuals who do not have such ties and whose

proposals are more socialist than those of the government itself. If these groups exist

and are able to survive in a repressive environment, it is because thousands of

people, for whatever reason, believe that systemic change is necessary. This is

evident in (or at least suggested by) the findings of the few reliable surveys

conducted in Cuba and the outcome of the general elections. (Dilla Alfonso 2006)

Civil society is slowly becoming stronger on the island, but not mobilised enough

to represent a direct path to regime change (see Otero & O'Bryan 2002). The

meaning of these trends should not be exaggerated, and only the basic conditions for

pluralism and an autonomous civil society are being created: Alternative spaces for expression of self identity and meaning have emerged or have

been strengthened in a process that has led to the creation of an incipient proto-civil

society. Youth, artists, and intellectuals have become more critical and daring in their

contestation of state ideology and praxis. Cubans of all walks of life are finding a

voice and a space, as small as it may be, to call their own. Groups of farmers have

formed independent cooperatives. Religious believers and women's groups have

become increasingly proactive in self-help ventures. (Fernández 2000, p113)

Castro has learnt from collapse of the Soviet Union and the rapid destabilisation of

communist governments in Eastern Europe and has opted for very little political

reform combined with strictly limited economic reforms (Robinson 2000, p122).

The continual pressure from the U.S., in fact, has allowed him to dismiss internal

opposition as U.S. dupes, and helped to mobilise a strong internal nationalism,

thereby reducing pressures for political opening (Robinson 2000, pp122-123).

Likewise, the positive immigration policy of the U.S., which readily receives Cuban

exiles, has been used by Cuba. In most cases until recently, more dangerous dissidents

have been arrested, and often offered their freedom so long as they leave Cuba

(Robinson 2000, p123), thereby reducing pressure on the regime. Recent U.S. laws

have made this even more predictable, with a guaranteed 20,000 U.S. visas for Cuba

annually, plus refuge for those viewed as political refugees, who can be readily

granted work permits and residency after one year (Robinson 2000, p124). On the

other hand, 'muted' discontent is very real within Cuba, especially among the

young (Robinson 2000, p125), in part due to lack of political freedoms, but also due

Lecture 4

19

to the economic difficulties the island has endured. Cuba's youth have different

experiences and expectations compared to their 'revolutionary' parents, a fact which

will be crucial in the future, post-Castro period (Dominguez 1999). This has been

confounded by difficult economic conditions, disillusionment, and a growing

recognition of increased drug use on the island (see San Martin 2003). On this basis,

the altering of the constitution to ensure that the ‘socialist system of government’

remains permanent and untouchable may reflect a sense that in the post-Castro period

such discontent may become much more open (BBC 2005a; Robles 2006). Likewise,

information networks remain strongly censored, and there was very limited

Internet and e-mail access on the island, with only some 20,000 Cubans having

official access to e-mail addresses, out of a population of 11 million, though this is

partly due to financial limitations when the average wage is about US$20 a month

(Smith 1999), though Cuba has plans to upgrade this in following years, while seeking

to retain some control of the information flows onto and out of the island (see

Schwartz 2003).

The key issue for Castro's government has been the re-linking of the economy to the

global capitalism system without the undermining its political system. Thus: Over the course of the 1990s Cuba has dramatically changed its trade, technology

and investment partners, modified its institutions of foreign trade, opened the door to

foreign investment, developed international tourism at a breathtaking pace, and

changed, albeit not so dramatically, the product composition of its exports. These

changes represent the beginnings of the country's reinsertion into the international

economy, or to be more precise, into the capitalist world system. This reinsertion - or

"relinking" - follows a previously long period of "delinking" from the same world

system, particularly during the 1980s. (Monreal & Hammond 1999)

One element of this modern Cuban strategy remains the effort to play a strong world

role in marshalling the politics of the developing world. This was clearly seen

when Cuba hosted the meeting of the G-77 developing nations (now in fact

comprising some 133 countries), including a visit by UN Secretary-General Kofi

Annan. Kofi Annan stated that he was impressed with the social development of

Cuba. Likewise, many Central and South American states have been very critical of

the U.S. led blockade of the islands (August 1999, pp21-22). Cuba is willing to raise

its profile in any international forum - it is probably on this basis that it has tried to

put itself forward as the 2012 venue for the Olympics (Excite News 2001a), an

unlikely bid but one that has drawn some media attention. In January 2004, Cuba also

hosted the 3rd Western Hemisphere Forum opposed to the Free Trade Area of

Americas (FTAA), 'with the participation of more than 1000 representatives of Latin

American social movements' (Xinhua 2004b). This trend has been continued through

2005-2006 with the effort to build alternative development paths for the Latin

American region. The Bolivarian Alternative for the Americas (ALBA), would

open up the economies of Cuba and Venezuela to each other, remove tariffs, and

would make use of Cuba’s ‘vast reservoir of human capital’ in return for low cost oil

(NACLA 2006). In the long term, by drawing in countries such as Bolivia, this could

emerge as a wider alternative energy network for Latin America.

Castro has also been willing to turn the tables on the U.S., which after the Cuban

Adjustment Act of 1966 would received any Cuban who could leave the island and

gain asylum in the U.S. on a preferential basis (Vanderbush & Haney 1999), thereby

Lecture 4

20

hoping to drain much of the talent from Cuba (Nackerud et al. 1999) as well as

creating a strong anti-Castro lobby in the U.S. This was in direct contrast to refugees

from Haiti, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua who had a much more difficult

task in supporting their refugee status claims. At times, Castro intentionally let

many of the disaffected leave the island. A total of over 1 million Cubans entered

America in this way, some through a Memorandum of Understanding between the

U.S. and Cuba that allowed 'Freedom Flights' between 1965 and 1973, while in 1980

Cuba allowed some 125,000 to leave the port of Mariel (Nackerud et al. 1999). It was

therefore predictable that during the tense period of the middle 1990s Castro was

willing for a time to open the doors of Cuba, letting any who wished to leave to do

so. As explained in one account: A new series of attempts by Cubans to leave the island began in the summer of 1994.

Initially the departures were largely be means of commandeering ships. Hijackings of

tugboats, ferries, and even a naval passenger transport ship took place in the Bay of

Havana between 13 July and 8 August. The hijackers were occasionally assisted by

the U.S. Coast Guard and later given political asylum in Miami. Frustrated by the

government's actions and accusing the United States of encouraging the departures,

President Fidel Castro announced that henceforth Cubans were free to leave the

island, and thousands of balseros (rafters) proceeded to leave on whatever small

rafts they could construct. (Vanderbush & Haney 1999)

The result was a wave of refugees that unsettled neighbouring Central American

states, as well as the U.S. More than 8,500 Cuban were temporarily housed in camps

in Panama (riots in these camps resulted in the deployment of 5,000 U.S. soldiers to

maintain security there), while some 28,000 were temporarily kept in safe haven

camps, many at the U.S. Naval Base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, a concession area

from the early 20th century (Nackerud et al. 1999; Williamson 1992, p439). The cost

to the U.S. of these emergency programs was over $300 million. In the end, an

agreement had to be reached whereby the U.S. would receive up to 20,000 Cuban

immigrants each year, but Cuba would not allow an uncontrolled exodus. The

ongoing trickle of refugees from the island continues to provide a kind of safety valve

for internal tensions, but also continued to heighten tensions between Cuba and the

U.S.

Castro has also moved to improve relations with the Vatican. For meetings with the

Pope in 1998 for the first time he wore a normal suit rather than military mufti. It

must be remembered that although many Cubans remained religious, Castro had

moved to remove the political influence of the Catholic Church by nationalising it

rather than letting its political leadership remain overseas: hence the creation of the

Episcopal Church of Cuba (August 1999, p25). The Pope has spoken out against the

embargo of Cuba, arguing that it hurts many ordinary Cubans (Newsday 1998). In

return for this diplomatic recognition, Castro has improved the ability of the

Catholic Church to operate on the island. Although only some 150,000 Cubans

openly practice their religion since controls on religious organisations were softened

in 1991, it is believed that many more are sympathetic, with some 40% being baptised

(Newsday 1998). Of course, Cuba has a wide range of its own syncretic Afro-Cuban

religious cults, including Ifa and Santeria that largely fall outside institutionalised

religious systems (see above).

Cuba has also been very active in promoting a critical view of the actions of the

U.S. globally. Hence it has been extremely vocal over the NATO air campaign in

Lecture 4

21

Kosovo in 1999, perhaps because it recognised that this pattern of humanitarian

intervention might make Cuba in turn a possible target (Robinson 2000, p122). In

May 1999 Castro launched a strong indictment of U.S. policies, but made sure that

there was no direct incident that could result in strengthened U.S. action against him

(Robinson 2000, pp122-123). Likewise, Cuba has scrupulously followed the 19941995 bilateral immigration accords it has made with the U.S., and has sought greater

cooperation in clamping down on the narcotics trade in the Caribbean, even asking for

U.S. training for its police in this area (Robinson 2000, p124). Recently, in May 2001,

proposals put forward by U.S. Foreign Relations Committee Chairman to provide

US$100 million in aid to Cuban dissidents was ironically 'endorsed' by the Cuban

government, which noted that receiving money from subversive foreign government

was a crime (Rice 2001). In the propaganda war with the U.S., Cuba has learnt to use

international media as well as its own information networks effectively. It thus

remained generally through 2001-2006 critical of the U.S. over Iraq, Iran, the FTAA

project, and Venezuela. From late 2001-2002 this criticism has been somewhat

reduced: in the light of the events of 11 September, Cuba argued that the U.S. had a

right to defend itself and detain suspects, but was continued about the role of largescale interventions in the name of the 'war on terror'. However, through early 2003,

Cuba moved to continue dialogue with Cuban exiles in Miami, with Cuba's top

'diplomat' (from the Cuban Interests Section in Washington) Dagoberto Rodriguez

meeting over a 100 people to talk about improved transport links, emigration, and US