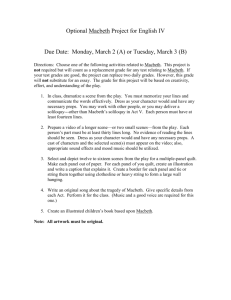

Macbeth Workshop Diary.doc

advertisement

Macbeth Workshop Diary Abbey Theatre Workshop on Macbeth for Teachers. The Voice Director at the Abbey Theatre, Andrea Ainsworth, facilitated a weekend workshop for teachers of English on Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Kevin Mc Dermott of the PDST attended and kept this workshop dairy Friday Evening There is something invigorating about meeting at the stage door of the Abbey, the national theatre, for a workshop on Macbeth. The fellow participants arrive from places as far flung as Limerick and Waterford, all filled with a similar feeling of expectation. After the gathering, our group of ten head over to the rehearsal space in Marlborough Lane to begin our session with Andrea Ainsworth, the voice director with the Abbey. Introduction and Warm Up Andrea gives a brief introduction and sets the scene for the next few days. The ambition will be to encourage each of us to speak the words of the play and to catch hold of Shakespeare’s language and rhythm. The workshop will invite us to consider the meaning of the words and explore the intentions or desires which the words serve. Through getting hold of the words we will get hold of the play. Over the weekend, we are going to unpick, animate and put back together a few key moments from the play. We begin with some breathing exercises. Andrea explains that the warm up is intended to free the breath by releasing any tension that inhibits breathing. We work from our feet up, keeping the knees loose, finding our balance, keeping our backs long and our shoulders easy. Andrea encourages us to extend our breath, using our abdominal muscles to control our breathing. Gradually we introduce sounds, playing with a sliding ‘o’ sound and the more percussive ‘ta’, ‘cha’ ‘pa’. Finally, we put gestures to sounds. It is an energetic and playful beginning, where we communicate through gesture and non-verbal sounds before moving on to words. Workshop 1. Act I Scene III, ‘This supernatural soliciting…’ We look at words – not phrases, or speeches or scenes, but individual words. Each participant is given an envelope which contains all the individual words of Macbeth’s first soliloquy (nouns, verbs, adjectives) printed on individual slips of paper: ‘fantastical’, ‘function’, ‘single’ ‘horrid’, ‘supernatural’, ‘horrible’, ‘heart’ and so on. The participants find a private space where they pick out words, one at a time. They look at the slip of paper, speak the word and add a gesture. The response is spontaneous. Having spoken all the words, each participant settles on their three favourites, refines how they wish to say them, and refines the gesture that accompanies them. The group re-assembles and forms a circle. Each participant says one word and the exercise continues until everyone has spoken his or her three words. The exercise is 1 Macbeth Workshop Diary repeated with more pace and people commit themselves more fully to each word and gesture. When the cycle is completed, a few things have become apparent. The first is that there are endless possibilities for saying each of the words, and it is by trying out some of the possibilities that we discover the word for ourselves. The second is that the exercise has helped the group to enter into the private world of Macbeth’s inner thoughts, desires and feelings. Now we read the soliloquy in the round, listening and looking for patterns and repetitions of words and sounds. We are given the speech printed on a white page. How clear it appears. How sharp our focus. Act I Scene III, 130-141 MACBETH This supernatural soliciting Cannot be ill, cannot be good. If ill, Why hath it given me earnest of success Commencing in a truth? I am Thane of Cawdor. If good, why do I yield to that suggestion Whose horrid image doth unfix my hair And make my seated heart knock at my ribs, Against the use of nature? Present fears Are less than horrible imaginings: My thought, whose murder yet is but fantastical, Shakes so my single state of man that function Is smother'd in surmise, and nothing is But what is not. Individuals offer their observations: the hissing ‘s’ sounds of the first line create a sinister effect; the thought is poised between ‘can’ and ‘not’, and the final repetition of ‘nothing’ and ‘not’, with their connotations of non-being and annihilation, suggests the dangerous territory into which Macbeth has stumbled; the repetition of ‘if’ and ‘why’ highlight the movement and direction of thought, the way it moves back and forth, as opposed to the substance of the thought. More generally, the act of speaking the words aloud increases the groups’ sensitivity to thought and language and the interplay between them. What does it mean to speak in short, exact phrases, or in longer, looser ones? In hearing the language, we gain an insight into the psychology of Macbeth and the way in which the imagination affects his body and his heart. Picking up on the idea that the thought moves back and forth, Andrea asks participants to form into pairs and read the soliloquy back and forth between them, changing speakers after every word. She suggests that the subject is one of such vital importance that every word counts and, accordingly, she asks that this be reflected in the way the participants commit to each word. Now the participants have a new layer added to the exercise. This time, changes of speaker are signalled by the punctuation points. In addition, the speakers are to be alert to the element of tension. These thoughts are treasonous. To speak them is to 2 Macbeth Workshop Diary conspire against the legal authority of the state. Each pair is engaged in an act of conspiracy. What they have to say must not be overheard by anyone in the room, or terrible consequences will befall them. To increase the sense of tension, Andrea moves through the room like a member of the Secret Police. Each pair has the opportunity to read the speech a number of times under these new circumstances. All agree that the exercise brings out the mixture of fear and excitement in the soliloquy, the tension between the private thoughts and the public articulation. There is some wonder that such a small amount of text provides so clear a window into the character and the play as a whole. Another shared insight is that having two say the speech forces us to listen and to notice more. Workshop 2 Macbeth’s soliloquy, Act I, Scene VII, ‘If it were done…’ MACBETH If it were done when 'tis done, then 'twere well It were done quickly: if the assassination Could trammel up the consequence, and catch With his surcease success; that but this blow Might be the be-all and the end-all here, But here, upon this bank and shoal of time, We'd jump the life to come. But in these cases We still have judgment here, that we but teach Bloody instructions, which, being taught, return To plague the inventor. This even-handed justice Commends the ingredients of our poison'd chalice To our own lips. He's here in double trust; First, as I am his kinsman and his subject, Strong both against the deed; then, as his host, Who should against his murderer shut the door, Not bear the knife myself. Besides, this Duncan Hath borne his faculties so meek, hath been So clear in his great office, that his virtues Will plead like angels, trumpet-tongued, against The deep damnation of his taking-off; And pity, like a naked new-born babe, Striding the blast, or heaven's cherubim, horsed Upon the sightless couriers of the air, Shall blow the horrid deed in every eye, That tears shall drown the wind. I have no spur To prick the sides of my intent, but only Vaulting ambition, which o'erleaps itself And falls on the other — The soliloquy has twenty-eight lines. We begin without much ado, standing in a circle, reading in the round, each participant reading to the next pause, as signalled by the punctuation. We are all concentrating, making sure we get our cues and hand the 3 Macbeth Workshop Diary speech on to the next person. And because we are concentrating so intently on each word, I begin to hear words that had never struck me before, like ‘here’ or ‘this’. And I notice that reading these small units of speech removes the fear that often attends reading Shakespeare. And when we have read the speech a few times, with different people leading, we pause and review how far we have travelled. Sitting on the floor, we talk about words and phrases that have entered our consciousness; how, for example, the word ‘assassination’ removes the ‘dirty deed in your own backyard’ quality from the prospective killing. Having spoken the words and felt the rhythm of the speech we are more conscious of how the language is heightened and the imagery becomes more elaborate as Macbeth seeks to persuade himself from the proposed action; how he builds himself up to proceed no further. Then we are on our feet again and Andrea directs us in an exercise that translates the movement of thought, and the pauses between each thought, into physical movement. We stand still to speak, speaking so that every moment, every word is important, without losing sight of the part the word plays in the larger unit. When we reach a pause, we gauge how long it is and walk what we think is a commensurate distance. It is a simple exercise yet it is extraordinarily effective in capturing the way the movement of thought moves forward in fits and starts, or hesitates and falls back. Then we try a variation on this exercise. We step through the thought, one step for each word. We feel how physically and emotionally tiring it is for Macbeth to find a path through these tangled thoughts. After an hour or so, the thought occurs to me that we are not at all concerned with whether the play is readable (a perennial preoccupation for us teachers) but are deep into exploring how these lines might be said. In quick succession, we do two further exercises. It the first, we work in pairs. We read the soliloquy, passing the speech back and forth to each other as the punctuation dictates, incorporating the different kinds of pauses we have now explored. We stand close and speak quietly, concentrating on catching the meaning of each word and speaking each section so that our partner can pick up the meaning and continue. We do the exercise a number of times alternating who begins the speech. More than any commentary or explication could convey, we understand how the soliloquy is a dramatic dialogue in which Macbeth debates with himself. In five minutes we have captured the drama of self-talk, how a soliloquy is a dialogue of self-persuasion. We are pleased with ourselves. But in this workshop, there is no resting on your laurels. The final exercise of the evening session follows after a discussion of the soliloquy is terms of what Macbeth wants: the kingship; what he must do to have it; and the consequences that will follow from acting to acquire it. Then we discuss the reasons, which dissuade Macbeth from pursuing his desire. We are in the realm of abstract concepts and ideas: desires; actions; consequences. Andrea asks us to consider how to make these abstractions more real, more tangible, and more playable. So we search for physical objects to represent a particular concept, drawing on the imagery of the speech to guide us but also selecting, in an arbitrary way, from the bits and pieces to hand: a chair represents the kingship Macbeth desires; a plastic bottle represents the consequences, the “poison’d chalice” 4 Macbeth Workshop Diary he will have to drink; a notebook stands for Duncan’s virtues. Each participant assembles his or her own set of physical properties to represent the key moral ideas. And then each of us, on our own, experiments with focussing on the appropriate object - holding it, sitting on it, looking at it - as we speak the words of the soliloquy, and we succeed in giving physical expression to ideas, desires and qualities. And as I play with the words and the objects, I realise how much the chair, the kingship, holds my attention and exerts an almost magnetic influence. What strikes me in this, and in the other exercises, is the way in which the workshop has us concentrating, focussing on the words and the extraordinary force and compression of the language. We have not ‘covered’ a great deal of the text of the play, but we have uncovered many things. That is something worth bringing from the rehearsal room to the classroom. Saturday Review We assemble on Saturday morning bright and early and review the workshop from the night before. Everyone is eager to contribute. We all have become more aware of how the soliloquy follows its own internal momentum. Andrea asks us to consider the points or points where the energy in the speech changes or renews itself and why this might be. This leads to a lengthy discussion that draws on the insights from the evening before. In particular, we pick up on the idea of the soliloquy as an act of self–persuasion. What has Macbeth to persuade himself from doing? Why does he need to do this, in the first place? For the first time, we bring in the back-story, the meeting with the witches, and the prophecy of the kingship to come. We consider the circumstances of that meeting - the general coming victorious from the bloody field, the feeling of luck and blessedness that goes with surviving a battle. When the witches speak to Macbeth, they speak to that feeling of luck. Is it this state of being, this state of luck and blessedness, that opens Macbeth’s mind to consider the possibility of something he would never have thought possible before? More generally, what circumstances stimulate states or feelings that make a character believe that the impossible is possible? It is an interesting discussion that looks to find a key that will help an actor play the part. It is also the kind of discussion that would help a student make sense of the tensions and inner conflicts that beset Macbeth. We have begun exploring the play at a point of energy and have now backtracked to help us explain the nature of that energy. It makes sense (and it works) to begin in this way, not at the beginning of the play, but at a key moment that is easily ‘got at’. Having considered the question of why Macbeth is contemplating murdering Duncan, we go back to the movement and momentum of the soliloquy. We discuss how Macbeth has to make Duncan ‘unkillable’; how he has to persuade himself that the deed is ‘undoable’ and how this is reflected in the language, imagery and rhythm of the speech. And we reflect on how the see-saw moments in the speech, the pauses for thought, the gathering of energy, and the decisive leap forward, are guided by the punctuation. I do not think I have ever paid more attention to punctuation marks in my life. I don’t think I have ever worked harder at trying to describe the effect of a mark: the comma which slows down without stopping the momentum; the semicolon which looks back to what precedes it as much as looks forward to what is to come; 5 Macbeth Workshop Diary and the colon which is really a gathering of energy before leaping forward. Wow! And it is only 11 o’clock on Saturday morning. After our coffee break, we read the soliloquy again, standing in a tight circle and we concentrate on committing ourselves to each word, not pulling back, and each person works to land his or her phrase so that the next person can take pick up it up, carry on and do the same for the next person. We do this a few times, and both the pace and the energy of our reading increase and there is a real sense of playing off each other, and for each other, and speaking as one. And the speech comes alive. And I think each of us has a better appreciation of this key speech than at any time before and we are more attuned to the nuance of each word. This has been achieved without any single person having the responsibility (or the burden) of reading the twenty-eight lines through on his or her own. There is a lesson in that for the classroom. And so we move on to the next part of the Act I, Scene VII where Lady Macbeth seeks her husband out. Workshop 3 Act I, Scene VII, ‘How now, what news…’ Enter LADY MACBETH MACBETH How now! what news? LADY MACBETH He has almost supp'd: why have you left the chamber? MACBETH Hath he ask'd for me? LADY MACBETH Know you not he has? MACBETH We will proceed no further in this business: He hath honour'd me of late; and I have bought Golden opinions from all sorts of people, Which would be worn now in their newest gloss, Not cast aside so soon. LADY MACBETH Was the hope drunk Wherein you dress'd yourself? hath it slept since? And wakes it now, to look so green and pale At what it did so freely? From this time Such I account thy love. Art thou afeard To be the same in thine own act and valour As thou art in desire? Wouldst thou have that 6 Macbeth Workshop Diary Which thou esteem'st the ornament of life, And live a coward in thine own esteem, Letting 'I dare not' wait upon 'I would,' Like the poor cat i' the adage? MACBETH Prithee, peace: I dare do all that may become a man; Who dares do more is none. LADY MACBETH What beast was't, then, That made you break this enterprise to me? When you durst do it, then you were a man; And, to be more than what you were, you would Be so much more the man. Nor time nor place Did then adhere, and yet you would make both: They have made themselves, and that their fitness now Does unmake you. I have given suck, and know How tender 'tis to love the babe that milks me: I would, while it was smiling in my face, Have pluck'd my nipple from his boneless gums, And dash'd the brains out, had I so sworn as you Have done to this. MACBETH If we should fail? LADY MACBETH We fail! But screw your courage to the sticking-place, And we'll not fail. When Duncan is asleep-Whereto the rather shall his day's hard journey Soundly invite him--his two chamberlains Will I with wine and wassail so convince That memory, the warder of the brain, Shall be a fume, and the receipt of reason A limbeck only: when in swinish sleep Their drenched natures lie as in a death, What cannot you and I perform upon The unguarded Duncan? what not put upon His spongy officers, who shall bear the guilt Of our great quell? MACBETH Bring forth men-children only; For thy undaunted mettle should compose Nothing but males. Will it not be received, When we have mark'd with blood those sleepy two 7 Macbeth Workshop Diary Of his own chamber and used their very daggers, That they have done't? LADY MACBETH Who dares receive it other, As we shall make our griefs and clamour roar Upon his death? MACBETH I am settled, and bend up Each corporal agent to this terrible feat. Away, and mock the time with fairest show: False face must hide what the false heart doth know. We bring chairs and sit in a wide circle and the conversation fills the circle. We begin by setting the scene, making clear what’s going on. Duncan has come to stay with Macbeth and Lady Macbeth. They are hosting a banquet for the king. Macbeth has left the table, thereby abandoning his guest of honour. Lady Macbeth comes to find him to bring him back. We read through the scene quickly and discuss some of the things which jump out at us. For example, there is a comment on the false note that Macbeth strikes when Lady Macbeth enters, “How now! what news!” He is covering his tracks, diverting her but she will not be put off and asks directly, “Why have you left the chamber?” He ignores the question and then announces his decision, in the way that a Managing Director might make an announcement on company policy, “We will proceed no further in this business.” Comment is made on the use of the word ‘bought’ by Macbeth in reference to good opinion and honour. Surely, these are earned, not bought? We note the way the drunk/hangover imagery is used by Lady Macbeth and the shifting of the ground from the impersonal use of “this business” by Macbeth to her “Such I account thy love.” Andrea asks us to remember what is ‘happening’ off stage. There is a banquet going on. The host and hostess cannot be away for too long. They do not have much time for this discussion, so there is a sense of urgency about it. Moreover, if they are to kill Duncan, proceed with the business, it will have to be done that night, so there’s an urgency about this that is reflected in words like ‘time’, ‘now’ and ‘do’. We reflect on the force of Lady Macbeth’s words, their effect and their implication: “If I had made the promise, this is what I would have done to fulfil it. That is how much I am committed to you and to this joint enterprise. So, how much are you committed to me?” At what point in the scene do we become aware that the energy and power has shifted from one to the other? At what point do we realise that Macbeth will surrender to her will? We look back to the soliloquy, which precedes this scene. Now it is clear that the imagery Macbeth created to convince himself, the elaborate, ornamental imagery of angels and cherubim, was artificial and the thing he desires is still alive and is refuelled by Lady Macbeth. We take a short break and when we come back together, we dispense with the chairs and stand in a circle, but it is a looser circle to the one we formed when we read the scene earlier in the day. By now I’ve become accustomed to the way we change 8 Macbeth Workshop Diary positions – standing, sitting, loose circle, tight circle, going off to a corner of the room to work on one’s own, finding a space to work with a partner – and the relationship between our configuration and the nature of the work in which we are engaged. For example, the loose circle suits the speculative, free-ranging discussion of interpretation while the tighter circle suits the focused reading of a scene. Every configuration brings its own kind of energy and carries an invitation to participate in the workshop activity in a different way. How might this be replicated in the classroom? Andrea leads the discussion inviting us to name what it is that Lady Macbeth wants. The suggestions come thick and fast: “She wants Macbeth back out at the banquet; she wants to know what’s going on; she wants him to come back to the plan…” From here we discuss the kinds of actions she takes to get what she wants: she questions; she undermines; she infantilizes; she mocks; she goads. There is discussion on the way something new is tried when an action meets an obstacle; when an intended act is blocked or meets resistance or refusal. Andrea observes how playing an action is more effective on stage than playing a state; how language serves the action, which in turn creates the state. This leads to a thoughtful silence as we, non-actors, think this through. So, Andrea sets up a scenario where we can experience for ourselves what she is talking about. In pairs, we are going to play with the idea of action and reaction. We have two words to play with, ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ and two actions: attraction and repulsion. What follows is an interesting game of cat-and-mouse, a pas de deux. My partner and I experiment taking turns to begin the chain of action and reaction. By inflexion, facial expression and movement, we give meaning to each ‘No’ or ‘Yes’, each trying to react to what has gone before and influence what will come next in the game; to cajole, block, dissuade, persuade, seduce or reject. It is an intriguing and dramatic game of chess, of movement and counter-movement. Both of us agree that the exercise brings home the way in which characters play off each other, and how the successful blocking of one avenue of advance leads to a new approach, a different action. When everyone has completed the exercise and given some informal feedback, we break for lunch. We reconvene and bring our chairs into a circle. We discuss the actions both Macbeth and Lady Macbeth wish to complete in this scene, the various objectives they wish to accomplish. From the exercise before lunch, we are aware that every objective or action is likely to produce a reaction or encounter resistance. In response to the questions, ‘What does he want in this scene?’ and ‘What does she want in this scene?’ we throw out loads of suggestions: He wants to call a halt. He wants to take charge. He wants to divert her, stall her, ignore her demands. She wants to challenge him, rebuke him, accuse him, undermine him. He wants to stick to his guns. She wants to confront him. She wants to make him feel guilty. 9 Macbeth Workshop Diary After a lively exchange of views, we are on our feet again and form into pairs. Andrea asks us to play the opening of the scene but instead of reciting the lines, we communicate what we want in a non-verbal way. We can make sounds but we cannot use words. The emphasis now falls on gesture, stance and movement. Again, it is a pas de deux, with one partner turning this way and that and the other following. It becomes a drama of flight and pursuit, of confrontation and evasion. Everyone is working with a different partner to the one from the earlier exercises, so there is a new dynamic at play in the room. We swap roles and discover numerous possibilities of playing the lines without speaking the words: Enter LADY MACBETH How now! what news? LADY MACBETH He has almost supp'd: why have you left the chamber? MACBETH Hath he ask'd for me? LADY MACBETH Know you not he has? MACBETH We will proceed no further in this business: We come back to the larger group and compare notes. Now we run right through the full scene, translating the entire text into a series of first person pronoun-verb-second person pronoun statements, of the kind ‘I interrogate you’, ‘I challenge you.’ As in other brainstorming sessions, the emphasis is on moving things along, not encouraging people to second-guess themselves. The result is a compendium of suggestions and some inventive word play and neologisms. My favourites are: “I high-horse you.” “I full-stop you.” “I guilt-trip you.” Other phrases which stay in my mind are: “I licence you”; I embolden you”; I bolster you.” I notice the alliterative patterns in some of the streams of statements or the onomatopoeic quality that creeps in as the litany gathers force and energy. If the soliloquies were exercises in self-persuasion, this scene plays as an episode in mutual delusion. Having explored the scene in this way, we stand in a close circle and read it in the round, twice in succession, moving from speaker to speaker as the punctuation dictates, working from one punctuation mark to the next. Then we read it twice more, though this time each speaker is free to read beyond the punctuation mark and pass on to the next person when he or she deems it appropriate. You can hear and see how the 10 Macbeth Workshop Diary work we have done on the scene has given each individual the confidence to deliver the words. We go back to pair work and do two exercises in quick succession. The first centres on the following exchange: MACBETH We will proceed no further in this business: He hath honour'd me of late; and I have bought Golden opinions from all sorts of people, Which would be worn now in their newest gloss, Not cast aside so soon. LADY MACBETH Was the hope drunk Wherein you dress'd yourself? hath it slept since? And wakes it now, to look so green and pale At what it did so freely? From this time Such I account thy love. Art thou afeard To be the same in thine own act and valour As thou art in desire? Wouldst thou have that Which thou esteem'st the ornament of life, And live a coward in thine own esteem, Letting 'I dare not' wait upon 'I would,' Like the poor cat i' the adage? It is a brilliant exercise. One person plays Macbeth, the other Lady Macbeth. As Macbeth says his lines, Lady Macbeth picks up on individual phrases and repeats them back, undermining all that is being said. The person reading Macbeth can repeat the phrase, reassert its power, before moving on. When Lady Macbeth delivers her lines, a similar process is repeated. Once we have run through the exercise a few times and develop our own way of playing it, we understand how it reinforces the push and pull in the scene, the play of power between them. And then we move on Lady Macbeth’s “What beast was’t then…” We give each, single word its moment, its weight and balance. We read in pairs, alternating every word so that each gets its due. In Andrea’s phrase, we unfix the speech, word by word, and discover the power of even the smallest word. The personal pronouns, the ‘I-You’ relationship, really jump off the page. I am struck by the force of ‘make’ and ‘unmake’; the various forms of the verb ‘do’ and the noun ‘time’. By really slowing down the reading, by making your way one word at a time, the scene reveals itself. I think of the many students who have been struck dumb with terror at the prospect of reading a large chunk of Shakespeare’s language; how they stumble over simple words as they skim forward trying to anticipate the words that might trip them up. Read, as we have done, one word at a time, takes away that fear. At this stage, having played with the separate parts of the scene it is time to put the whole thing back together. We again read in the round. This time we read each speech in its entirety and get a feel for the movement of the whole scene. 11 Macbeth Workshop Diary Then, in pairs, we play the whole scene, putting movement and gesture to the words, and there are five games of pursuit and fight in the room. Now full of energy, we from a tight circle and read in the round, reading from pause to pause, bringing every shred of understanding to each word. It is an electrifying reading and a fitting end to the day’s work. Sunday Review Its tea and coffee to begin and we chat about what we have experienced so far and how different this way of exploring the play is to the way most of us have taught it in the classroom. There is general agreement that we want to bring more of this kind of exploration into our classroom. Workshop 4, Act III, Scene I, Macbeth’s soliloquy, ‘To be thus is nothing…” MACBETH To be thus is nothing, But to be safely thus. Our fears in Banquo Stick deep; and in his royalty of nature Reigns that which would be fear'd. 'Tis much he dares; And, to that dauntless temper of his mind, He hath a wisdom that doth guide his valour To act in safety. There is none but he Whose being I do fear: and, under him, My Genius is rebuked; as, it is said, Mark Antony's was by Caesar. He chid the sisters When first they put the name of king upon me, And bade them speak to him; then prophet-like They hail'd him father to a line of kings: Upon my head they placed a fruitless crown, And put a barren sceptre in my gripe, Thence to be wrench'd with an unlineal hand, No son of mine succeeding. If 't be so, For Banquo's issue have I filed my mind; For them the gracious Duncan have I murder'd; Put rancours in the vessel of my peace Only for them; and mine eternal jewel Given to the common enemy of man, To make them kings, the seed of Banquo kings! Rather than so, come fate into the list, And champion me to the utterance! Who's there? We stand in a circle and do a choral reading of the twenty-five lines of the soliloquy. There is safety in numbers and the voices rise and fall more or less in unison, like the prayers at Benediction. We give a quick response. A number of words are commented on, words which have some meat on their bones, like ‘stick’ in line three. 12 Macbeth Workshop Diary This leads to a discussion of the way in which Macbeth tortures himself in the soliloquy and fills his mind with a host of characters whose presence drives him to distraction: Banquo; ‘Banquo’s issue’; Duncan. The soliloquy is like a scene played between Macbeth and a number of characters. Taking up the idea of the people who populate the speech, Andrea suggests that we find objects to represent the most important characters conjured in the speech. For the second time over the weekend, each of us assembles a set of properties from the odds and end around the room and in our pockets and rucksacks. The idea is that we will do the speech and speak or address the important characters through the objects which represent them. When Macbeth refers to himself, we touch our heart or make a similar gesture. Each person works on his or her own. At first, I find it hard to project anything onto the odds and ends before me. However, as I read the speech over, one thing becomes clearer and clearer to me: the real anger and frustration in the soliloquy is directed at ‘Banquo’s issue’, ‘the seed of Banquo’. I experiment with reciting the lines, with finding the point where the energy quickens and intensifies. I use the punctuation and the pauses to guide me. In one reading, I kick out at the object representing ‘Banquo’s issue’ and repeat the action at the next four mentions of them. The effect is staggering. I feel I have uncovered the Macbeth whose murderers kill Macduff’s son. We pause to compare notes and soon everyone is using a physical gesture to match the fury of Macbeth. Before we know it, shoes and runners are kicked around the room. When we stop there is agreement that the exercise has helped us to embody the anger and darkness at the heart of the play. It is one thing to talk about darkness and cruelty in a discursive way; it is quite another to find yourself lashing out in anger at the object of your hatred. We leave our individual work and reform as a group. This time we set up a wider circle. We are going to read the soliloquy in the round, going from pause to pause but there are some additional elements to the way we will play it. For starters, each person will step into the centre of the circle to deliver his or her portion of the speech. Secondly, the rest of the group will make some verbal response to what has been said. In other words, we create a chorus (or a rabble) and the reaction of the group, like the reaction of a crowd at a sporting event, spurs each person to deliver each word as powerfully and tellingly as possible. Standing in the middle, meeting the eyes of those in the circle, you want to persuade them, to convince them of the truth of what you are saying. It is not all shouting, though there is some. There is also low intensity, quiet fury and murderous intent. In playing the soliloquy in this way, we see that Macbeth is his own rabble; “I rabble myself” might be his dictum. When we finish there is a terrific feeling of shared accomplishment, of having made something interesting and revelatory happen. I suppose it is the feeling that animates a company when the playing comes together to produce something that could not be produced by one person alone. I hope it is the feeling that you find in classrooms when the class group generate insights and understanding from class discussion or interaction. Concluding Remarks Of Punctuation and the Verse Line 13 Macbeth Workshop Diary The workshop has almost come to an end. Before we conclude, Andrea goes back to the different sections that make up a speech: the units of punctuation, the sentences and the verse lines. We discuss how the punctuation - the commas, semi-colons, colons and full stops – influence and control the movement of thought. Andrea invites us to consider the punctuation points as dynamic, as directing us forward, how characters are never as interesting as the thought they are going to express next. She raises a number of questions; offers some definitions. What is a comma? It is not a stop. It is more like a speed bump on the road which slows you down but which you cross over. In terms of the movement of thought, it slows it down without really altering the course. The semicolon is a pivotal point, like the one on a seesaw, which rocks one way then the other. A semi-colon contains within it the notion of equivalence: what goes before it is as important as what comes after. A semicolon gives pause for thought. The colon has the effect of pushing both the speaker and the thought forward into the list or the definition which follows it. The colon creates a jump forward. The full stop brings you to a halt. It is not a temporary pause; it is not a seesaw moment; it is not a leap forward: it is a full stop. Each of us takes the soliloquy (“To be thus is nothing…) and experiments with different ways of marking the pauses. We are all on out feet and try to mirror in a physical way the effect of the punctuation marks. For example, a comma is marked by a small change in the rate of walking; a semi-colon is signalled by a re-tracing on your steps before moving forward; a colon brings a leap forward; the full stop brings you to a standstill. The exercise is fun to do, inventive and instructive. Each person works out their own way of marking the pauses. However, what is abundantly clear is that everyone is interpreting the movement of Macbeth’s thoughts through the punctuation. The punctuation is central to our interpretation. Would my classroom was as creative a space as the rehearsal room! The final part of the workshop is giving over to some consideration of the verse line and the necessary tension that exists between the language as structured by the logic of the punctuation and the language as structured by the blank verse. How often has this featured in my classroom, I ask myself. You can guess the answer. Yet anyone speaking Shakespeare’s language cannot be unaware of the underlying verse structure. I am interested to see how an actor or a voice director approaches Shakespearean verse. Andrea suggests that the verse line is a way of organising thought within a soundscape of five beats and five off-beats. Not every line conforms to the iambic pattern. Some lines may begin with a stressed beat followed by an unstressed, a trochee as opposed to an iambus, or the five stressed syllables may not be evenly stressed. In some places, there are more than beats in the line and the line seems to push against its own structure. However, for all those variations, the underlying pattern is clear and the trace of the iambic pentameter underscores the language of the play. To experience this, we read some lines and clap the stressed beats. Andrea directs us to use a spring movement of the hand rather than a clapping one to catch the lift and thrum of the beat. For those using their foot to tap out the beat, they are instructed to mark it with the foot coming up off the floor rather than treading down. The effect is to energise the line rather than beat it into submission. We follow this exercise with a reading of the soliloquy (“To be thus…”) where we take a breath at the end of every line of verse. In a way I had not anticipated, this way of reading observes sense even as it goes against common sense. Of course, the effect of trumpeting the verse 14 Macbeth Workshop Diary structure over the grammatical sense is to create an artificial way of speaking the language. However, Andrea argues that it is possible to play the sense and honour the verse line even as you push against it. The experiment of pausing at the end of every line allows you to hear a Macbeth whose thoughts are almost at breaking point. There is a paradox that, in observing the measure of the verse, you almost lose the measure of the thought. These experimental readings lead to a discussion of the caesura. There is general agreement that this pause can mark the acceleration of thought as much as its slowing down. However, before we accelerate into further discussion, the workshop comes to an end. The clock has beaten us. As we gather our belongings, we all determined to bring as much of the spirit of the workshop into our classrooms: the spirit of fun and inventiveness; the spirit of interrogation; the spirit of communal learning and discovery. And as I make my way home, I wonder if it is too late to change careers? Kevin Mc Dermott 15 Macbeth Workshop Diary 16