The 13th Annual International Scientific Conference

advertisement

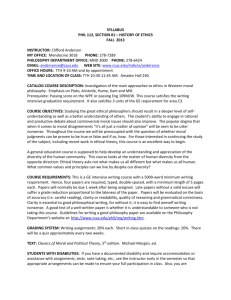

Prof. dr. sc. Maja Žitinski University of Dubrovnik Ćira Carića 4 20000 Dubrovnik Tel. 020/445 734; 020/450 115 GSM 091/550 85 63 Fax. 020/435 590 E-mail: zitinski@unidu.hr mzitinski@du.htnet.hr The 13th Annual International Scientific Conference »The Days of Frane Petrić« Main topic: »Philosophy and Education in Contemporary Society« Croatian Association of Philosophy, Cres, Croatia, September 20th – 22nd 2004 The Concept of Education Pojam obrazovanja Summary Education itself is a concept that has a standard or a norm, which gives the education its purpose. In education a judgment of value is necessarily implied. Most disputes about aims of education refer to the distinction between two terms: “educere” (to lead out), and “educare” (to train). Leading out requires treating a student with respect as a person, where to become educated is to learn to be a person. Training views a student as “material” to be poured into an adult mould. The concept of training, unlike that of education, has no logical connection with values. The paper examines various procedures, required to attain the virtue of knowledge. The use of authority as a principle of educating procedure implies inducing the student to come to conclusions which the teacher himself intends him to make but which the subject matter does not necessarily demand. Education does not only reflect social changes that have already occurred, rather it should take an active part in directing social change. Hence, indoctrination and other rationalizations should be stated as immoral way to treat a student. Sažetak Pojam obrazovanja podrazumijeva neki standard ili normu koja će obrazovanju dati svrhu. Vrijednosni sudovi su u obrazovanju konstitutivni. Većina rasprava o ciljevima obrazovanja se odnosi na razliku među pojmovima “educere” (izvoditi), i “educare” (uvježbavati). Izvoditi, potražuje odnos prema studentu kao osobi, pri čemu se smatra kako postati obrazovan znači naučiti biti osoba. Uvježbavanje ili izobrazba na studenta gleda kao na objekt koji se treba približiti stereotipu. Za razliku od obrazovanja, izobrazba nije logički povezana s moralnim vrijednostima. Referat preispituje raznovrsne procedure koje vode prema unutarnjoj vrijednosti samoga znanja. Ukoliko su u obrazovnoj proceduri autoriteti najvažniji, onda će studenti morati prihvaćati one zaključke koje će im autoritet nametnuti i onda kad po naravi stvari takvi zaključci nisu opravdani. Obrazovanje ne odražava samo one promjene koje su se u društvu već dogodile, ono treba zauzeti aktivnu ulogu u pronalaženju pravaca društevenih promjena. Zbog toga, indoktrinaciju i ostale racionalizacije treba smatrati nemoralnim načinom odnosa prema studentima. Key words: education; extrinsic and intrinsic values; learning; indoctrination; moral justification Introduction The role of education is not only to reflect social values, but also to develop rationality and avoid irrational and hence repressive social influences. Therefore philosophy of education must highlight the distinction between coercive aspect of education, and moral aspect of education. Obviously, a good or serious learner must learn certain things that have permanent and universal applicability to man as such. That is, the student’s intellectual integrity and capacity for independent judgment springs from the intrinsic meaning of education. Extensive knowledge does not reefer only to the facts, it reefers predominantly to the evaluative aspects of knowledge and therefore it must involve the whole personality. An autonomous judgment becomes the precondition of the moral aspect of education because it does not aim at utility, it aims at what is good and therefore, right. The purpose and the content of education depend on both: the political view upon the role of individual in particular society, and his readiness to challenge indoctrination, propaganda, and rationalizations. Where does the Education Stem from? It is not uncommon that some philosophers of education strive to provide a more or less static definition of education. Yet, any definition that would leave out the social and political prospective of education, but would match only the scope of understanding and enhancing values of the inherited culture, must be ideological! That is, authoritarian regimes have a very strong political interest to maintain “static” moral ideals, generated by particularistic world-views, and give priority to the goals of specific groups. This is the reason why instrumental (extrinsic) values are not being clearly distinguished from profound (intrinsic) values. John Wilson (from the Department of Educational Studies, Oxford University) will also disagree with those who claim that education has nothing to do with politics! He stated: “such a definition of education is conservative, and thus political.”1 Some modern philosophers of education - due to their obscure definition of educational goals - confuse terms of upbringing /trophé/, child rearing, and training with the term education /paideia/. Obviously, unclear prospective upon the ultimate end of education, lowers understanding in these areas. Have we advanced very much on that, what Plato and Aristotle have said about turning away from whatever is not virtuous in education? 1 Wilson, John: Preface to the Philosophy of Education, pg. 48 2 Both, Plato and Aristotle overtly reinforced that the quest for characterbuilding, and intellectual maturity must presuppose a certain moral, or political ideal. Plato2 identified such ideal clearly defining the term “education” as follows: “When we say that one of us is educated and the other uneducated, we sometimes use this latter term of men who have in fact had a thorough education – one directed towards petty trade or the merchant-shipping business, or something like that. But I take it for the purpose of the present discussion we are not going to treat this sort of thing as ‘education’; what we have in mind is education from childhood in virtue, which produces a keen desire to become a perfect citizen who knows how to rule and be ruled as justice demands. I suppose we should want to mark off this sort of upbringing (trophé) from others and reserve the title ‘education’ for it alone. An upbringing directed to acquiring money or a robust physique, or even to some intellectual facility not guided by reason and justice, we should want to call coarse and illiberal, and say that it had no claim whatever to be called education. Still, let’s not quibble over a name; let’s stick to the proposition we agreed on just now: as a rule, men with a correct education become good.” Aristotle identified education in normative, or moral terms by assuming that education does not aim at utility, since training, does. That is, Aristotle’s moral ideal of education is rooted in the quest for deliberate autonomous choice, and has nothing to do with the non-moral uses of value words (right, wrong, ought, must not). The difference between the moral, and the non-moral uses of value words occurs not between right and wrong, but between (instrumental) right and (moral) right! Hence, instrumental right does not equal moral right, but moral right does equal both, instrumental, and moral right! Moral reasons are not something we find in the world; rather we impose them upon the world through the construction of our knowledge3 and through our actions. For Aristotle education is a moral concept because it goes beyond instrumental right. Aristotle’s4 view unfolds as follows: “The animals other than man live by appearances and memories and have but little of connected experience; but the human race lives also by art5 and reasonings… … yet we think that knowledge and understanding belong to art rather than to experience, and we suppose artists to be wiser than men of experience; and this because the former know the cause, but the latter do not. And in general it is a sign of the man who knows and of the man who does not know, that the former can teach, and therefore we think art more truly knowledge than experience is; for artists can teach, and men of 2 Plato: Laws, Translation by T. J. Saunders, 643-4 In Kantian theory if a judgment were analytically true, experience would not be needed to justify its truth. Morality is concerned with practical questions, that is, not with the ways things are, but with the way things ought to be done! Since experience tells us only about the way things are experience does not provide answers to our practical questions! 4 Aristotle: Metaphysics, 980 b 25 – 981 b 20 (From: The Basic Works of Aristotle, Edited and with an Introduction by Richard McKeon), pg. 689 - 690 5 the expression of human creative talent 3 3 mere experience cannot. … But as more arts were invented, and some were directed to the necessities of life, others to recreation, the inventors of the latter were naturally always regarded as wiser than the inventors of the former, because their branches of knowledge did not aim at utility.” Education is not a Fact but a Process If human personality were defined in biological terms, man will grow automatically! But, if human personality were defined in cultural terms, men will need education. Nevertheless, there is much disagreement about the content that people as autonomous and rational creatures are logically required to obtain, if they whish to become educated. Wilson6 considered that knowledge and understanding should be favored because it is hardly possible not to be concerned with learning and the objectives of learning while advocating about what ought to be taught and learned. Obviously, education must be a practical social activity, since it presupposes two sides: the educator, and those who aim to acquire education. As a social activity, education is likely to reflect ideology of the society or group using it. Therefore, it always requires it’s own values be justified! In transition countries, the political and economic system still holds a significant position in determining the ideological goal of the society. The question is not whether education should take part in this process, but whether its contribution would be irresponsible, or it would be concerned with maximum intelligence in reexamining the system’s values and their implications. Since learning requires time, becoming a person appears to be a matter of degree, and it is acquired through a process. Each teaching and learning situation is the personal creation of those experiencing it, so if the Horward Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences (published in 1983) were recognized, education could change its format extensively. (Gardner outlined seven7 intelligences: linguistic, logical-mathematical, spatial, musical, bodily kinesthetic, interpersonal and intrapersonal). Dearden8 proposed that the distinction between “information” and “judgment” is a distinction between different manners of communication rather than a dichotomy in what is known. It springs from reflecting upon teaching and learning rather than from reflecting the nature of knowledge. That is, education has an instrumental potential in causing change because its role is not only to reflect values of the society, but help to modify inappropriate practices! And as Sternberg9 rightfully admitted, what counts as morally right action depends on objectives! 6 Wilson, John: Preface to the Philosophy of Education, pg. 53 Sharon L. Silverman,& Casazza; Martha E.: Learning & Development – Making Connections to Enhance Teaching, pg. 34 8 R. F. Dearden: Instruction and Learning By discovery (From: Peters, R. S. /editor/: The Concept of Education, (Contributors: R. S. Peters; D. W. Hamlyn; Paul H. Hirst; G. Vesey; R. F. Dearden; Max Black; Gilbert Ryle; Israel Scheffler; Michael Oakeshott; J. P. White; John Passmore), pg. 170 9 Elaine Sternberg: Just Business – Business Ethics in Action, pg. 4 7 4 In spite of the fact that values are the result of both, socio-economic background and education, values are never simple, biologically given and indubitable entities. In his introduction to Aims in Education Hollins10 assumes that values do not exist in vacuum waiting for an object. What we desire depends entirely on what objects of desire have been presented to us. We learn to want things. Our desires have a history and not just a biological history, but a rational, social history of intelligible response to what we are offered. But those who want to give the public what they want the public to want, fail to admit how unethical behavior arises from the internalization of the executive’s values. “What is lost in this is the concept of the criterion of autonomous critical taste, of people who can defend themselves both, the advertisers and the educators.” Intrinsic and Extrinsic Aspects of Education Throughout the history of education educators have been concerned with the formulation of aims in education. If those aims were determined in implicit language, consisted of ambiguous and abstract terms, then no empirical procedure can neither falsify nor confirm them! As Richard S Peters11 stated, the conviction that an educator must have aims is generated by the concept of “education” itself, because to speak about education is to commit oneself to a judgment of value. In this respect education is commonly considered valuable in extrinsic terms for both, the individual (he will get a better job), and the society (good citizens will be developed). But education can also be conceived in intrinsic terms. That is, as Langford12 forges, in formal education two parties may be distinguished, one of whom, the teacher, accepts responsibility for the education of the other. Informal education is defined negatively as education in which this condition is not met. In these definitions the word education is left undefined. As indicated earlier13, Aristotle forged the view that Wisdom emerges from knowledge of artists who seek after truth and meaning in a creative manner, and therefore pressures of the necessities of life do not influence their activity primarily. That is, Aristotle’s scope of education definitely referees to the term “educere” (to lead out), because it enhances individual’s expertise and results in self-development, and in realization of individual potentialities. In other words, education’s goal is, learn to be a person. Accordingly, good society will be a society of fully developed persons with their unique freedom and responsibility. But, if education were viewed as if it stemmed solely from the term “educare” (to train), then it would be more or less equated with upbringing. Wilson14 exposed his idea of the difference between a trained teacher and an educated teacher. In his view, both sorts of learning may benefit the teacher and Hollins, T. H. B. (editor): Aims in Education – The Philosophic Approach, pg. 7 - 8 John Martin Rich (editor): Readings in the Philosophy of Education, pg. 37 12 Glenn Langford & O'Connor D. J. (editors): New Essays in the Philosophy of Education, pg. 3-4 13 See footnote number 4 14 John Wilson: Preface to the Philosophy of Education, 23 10 11 5 his pupils. The difference is rather that the notion of education covers more ground, or takes more things into consideration, than the notion of training. As Natale15 emphasized, theory and practice are never far apart or separated; the one remains corrective for the other. If the system’s values and their implications were constantly reexamined, than the protest against treating children as material to be poured into an adult mould should be the source of permanent revising educational principles and procedures. Whether the debate would refer to any procedure of teaching and learning such as training, conditioning, rational explanation, one is for sure: a child should be treated with respect as a person. If the educator is not concerned with the growth of the child’s personality, but deliberately instills his own beliefs into a child, he displays an unacceptable behavior! That is, he uses the child as a means, instead of treating him as an end! Whether such educator is, or is not aware of such unethical practices, he provides incomplete and therefore false and misleading information, hence, he bears responsibility for contributing to a very serious social problem! Descriptive and Prescriptive Elements of Education Education can only escape from misconceiving its purpose by allowing its core assumptions to be challenged. So, the ability to access, analyze, evaluate and communicate information in all its forms requires the educated person to recognize if half-truth has been taught instead whole truth, by either giving only one point of view or by suppressing other possible points of view. Such extensive knowledge goes beyond the facts, and this is the reason why the attainment of extensive knowledge could not be the result of training solely! This idea has been emphasized by Cornford16, (who admitted how Theaetetus has been led to see that knowledge must be sought above the level of mere sensation or perception, somewhere in the field of that “thinking” or “judging” which has been described as an activity of the mind “by itself”). The extensive knowledge is the sort of experience that has the profound evaluative character; it referees to the understanding of the very nature of education itself (which is considered valuable in and for itself)! According to the fact that experience tells us only about the way things are, and not the way things ought to be, extensive knowledge must be the exclusive result of education! Or, as Daveney17 in his paper on education stated, the fact that you are being trained for something does not imply that you are being educated. The implication being that the concept of training, unlike that of education, has no logical connection with values. The difference between the two, lies in the difference between empirical facts and moral evaluations. Training is an empirical concept, “divorced” from moral values. 15 Samuel M. Natale: Ethics and Morals in Business, pg. 14 Francis MacDonald Cornford: Plato's Theory of Knowledge – The Theaetetus and the Sophist of Plato, (Theaetetus 187 A), pg. 109 17 Glenn Langford & O'Connor D. J. (editors): New Essays in the Philosophy of Education, pg. 84 16 6 Educational aims cannot remain static; in order to provide the development of rationality in children they require the critical reappraisal of content and method. In Harris18 view, education involves the whole personality, and training touches only the surface of the mind. The danger of thinking of the “static content” of education is that one may confuse the content with education itself. And teachers who concentrate on content rather than on education will instruct rather than educate. A value judgment differs from all other sorts of judgment. Its validity depends on whether it is significant on the range of profound humane interest, and not whether it is well accepted into a particular community. We cannot infer values. We can only discover how people define them. Values are enduring and resistant to change because they are tied to fundamental human needs. If ethical judgments were simply conformity statements about particularistic world views, than values would be arbitrarily invented, and it would be impossible to argue about questions of value! The job of evaluative statements is not only to express the agent’s approval, but also to present his appraisal! So, Thomas E. Hill19 proclaimed that sensory and observational truth conditions show little light upon the meanings of evaluative statements. Evaluative statements must rely upon an apriori judgment and are appropriate without reference to experience. And Searle 20 asserted, evaluative statements must be different from descriptive statements otherwise, they could no longer function to evaluate. Normative concepts are irreducible to empirical concepts, they simply constitute the way we make and justify our ethical appraisals. The debate about what kinds of differences are ethically relevant and which values and principles are fundamental depends upon the right decision. For Cornel M. Hamm & L. B. Daniels21 education is also a normative concept, because it implies the conceptual connection between education and what is valuable. This means that the purpose of formal education is always directed towards shaping values recognized by the particular political system. Hence education institutionalizes social values and makes known what the sociopolitical aspect of a particular culture is. Unfortunately, in every society education is sometimes dominated by irrational or repressive factors, such as popular opinion, local prejudices, and national demands. Authoritarian22 systems of education very commonly produce pupils who are extremely critical, but only of those who do not fully adhere to the accepted beliefs, the accepted rules and the accepted modes of action. 18 Alan Harris: Thinking about Education, pg. 6 - 7 Thomas E. Hill: The Concept of Meaning, pg. 210 20 John R. Searle: How to Derive ‘Ought’ from ‘Is’ (From: Theories of Ethics, Edited by Philippa Foot), pg. 110 21 Cornel M. Hamm & L. B. Daniels: Moral Education in Relation to Values Education (From: Cochrane; Hamm; Kazepides: The Domain of Moral Education) pg. 17 22 John Passmore: On Teaching to be Critical (From: Peters, R. S. /editor/: The Concept of Education, (Contributors: R. S. Peters; D. W. Hamlyn; Paul H. Hirst; G. Vesey; R. F. Dearden; Max Black; Gilbert Ryle; Israel Scheffler; Michael Oakeshott; J. P. White; John Passmore), pg. 197 - 199 19 7 Education and Indoctrination Education covers a much wider area than indoctrination not simply because education does not exclude other opinions from the available evidence. Education implies the willingness “to detect nonsense, employ linguistic clarity as a defense against their own and other people’s fantasies, grasp what a conceptual question was and what sort of treatment it required, identify such questions in practice”23 In the view of Patricia Smart24 indoctrination occurs when evidence is absent or insufficient for the degree of belief accredited to it, that is, the educator is concerned with offering reasons, the indoctrinator with offering rationalizations. She concludes, if we are to avoid indoctrination, the beliefs we teach must be rational. Yet, rationality must imply possible alternatives so that the accepted beliefs can be subjected to criticism and replaced by moral reason and moral argument. That is, whether a proposition will indoctrinate or not, depends upon how far we are prepared to allow it’s refutability. The fundamental difference between the educator and the indoctrinator is that the indoctrinator treats all rules as “inherent in the nature of things” and he deifies them as if rules are beyond the reach of rational criticism. On the other hand, the educator welcomes criticisms and is clear about what he is doing, and even more important, what he is not doing. In all authoritarian schools, secular or ecclesiastical, the teacher counts himself successful when his pupils leave their school holding certain beliefs so powerful that no future experience could shake them; so committed to certain habits of behavior that any modification of them will induce overwhelming feelings of guilt. (Their unquestioning obedience can be counted upon). Wilson25 rightfully emphasized how heavy the responsibility on the teaching profession is, not to indoctrinate! In his view, the teaching profession has no right to pass its irrationality to the children, because good teachers are not wholly the instruments of society, they are its leaders in some sense. Wilson proposed that although teaching science or modern languages can be plainly useful, it does not develop and enlarge the personality in the same way as teaching and discussion of these problems and areas of discourse with which people are intimately concerned: discussion of their feelings, their moral behavior, their religious aspirations, their practical choices. Richard Hare26 indicated that indoctrination begins when we are trying to stop the growth in our children of the capacity to think for themselves about moral questions. Methods will be bad if they are used to produce attitudes that are not open to argument, hence none of the thoughts that may occur to students should not be labeled as “dangerous” apriori. 23 John Wilson: Preface to the Philosophy of Education, pg. 2 Patricia Smart: The Concept of Indoctrination (From: Langford, Glenn & O'Connor D. J. /editors/: New Essays in the Philosophy of Education), pg. 38 - 42 25 John Wilson: Education and Indoctrination (From: Hollins, T. H. B. /editor/: Aims in Education – The Philosophic Approach), pg. 44 26 Hollins, T. H. B. /editor/: Aims in Education – The Philosophic Approach, pg. 52 24 8 Why Education and Ethics must Interfere The given social order including law and custom contains social rules, which represent the coercive aspect of what is regarded “as a good life of the best possible life”. By contrast, a moral order for a society is an order, which actually accomplishes the purpose of education by forging people to selfdevelopment. Every human being is capable to become morally autonomous, but without formal education it would be very difficult to obtain an objective prospective for judging events. But there is a consensus among philosophers27 that one of the most important goals of education should be the liberation of students from uncritical mental habits. They cannot be expected to respect themselves as persons unless they have learned to utilize fully the intellectual and creative powers with which they are equipped. In order to acquire any firm stand against indoctrination or to become aware of the distinction between the ultimate morality and utilitarian morality, everybody should aim to self-development. Thus the distinction between coercive aspect of education and moral aspect of education emerge. Moral education can be established exclusively through encouraging analytical attitudes that distinguish descriptive from prescriptive assertions. Moral autonomy is the fundamental criterion for identification of what is good and therefore what is right. Dearden28 pointed out that with Kant the concept of autonomy is applied primarily to the individual person. But, Kant’s notion of personal autonomy serves also to combine personal autonomy with the logical autonomy of moral discourse of which the social dynamics in fact consists of. That is why arguments about the purpose of education differ widely in accordance with views about what sort of society ought to exist. Harris29 presented the image of the primitive agricultural society, which is constituted of 70 per cent slaves and 30 per cent ruling class. Since they have no career to prepare for, what is it necessary for them to learn, what sort of curriculum would be appropriate, beyond religious instruction and sport? Presumably the priests will need to exercise power over the slaves. The slaves do not expect an after-life because they do not believe they have souls – life on earth is all they have. It is assumed that all the priests are men, and all the power lies in their hands. As with any class system, political power lies in the hands of minority. Why is indoctrination (rather than education) necessary if the society is to preserve its existing structure? Why would real education for the slaves be undesirable in the eyes of the priests? As Daveney30 indicated, if you have a very clear notion of the function of the state, you will have a pretty clear view of the education your citizens ought to 27 Matthew Lipman; Sharp, Ann Margaret; Oscanyan, Frederick, S.: Philosophy in the Classroom, pg. 62 28 R. F. Dearden: Autonomy as an Educational Ideal (From: Brown S. C. /editor/ Philosophers Discuss Education, pg. 3 - 4 29 Alan Harris: Thinking About Education, pg. 16 - 17 30 T. F. Daveney: Education – a moral concept (From: Langford, Glenn & O'Connor D. J. (editors): New Essays in the Philosophy of Education), pg. 91 9 have. This means that as much as the purpose of education varies, so would the content. For example, in regimes that claim to be democratic but in fact rule authoritarian, there is no need to create in those who are ruled, “the cultural selfunderstanding consistent with principles underlying governmental authority.”31 That is, the rule is not aimed to be accountable to the public! In such regimes, identities obtained within a family, ethnic, class, or religious life, are considered to be sufficient to produce identities consistent with the authority of the regime. Authoritarianism lowers the integrity of the public sphere since it hides relevant information, hence, prevents citizens from carrying out the duty to make a qualified choice! Hence, authoritarianism might be held accountable for, as Wilhelm von Humboldt32 noted, attacking the “inner life of the soul, in which the individuality of human beings essentially consists”. Therefore, Daveney asserts that the educational debate is in fact a debate about society, and this is the reason why the question on “Education for what?” is virtually unanswerable. As Harris33 indicated that education in not a subject in any simple sense because there is a sharp contrast between the educational ideals of a democracy and those of a totalitarian state. The former, at least in principle, places value on freedom of political thinking, the latter valuing uncritical loyalty and the subservience of individual desires to the welfare of the “State”. Conclusion The debate about the areas that fall under the domain of education refer rather to the objectives of teaching and learning, than to the specific content. Many contemporary philosophers of education confirm to Plato and Aristotle who claim that the purpose of education is to challenge students to acquire an independent mind. Only individuals who gain integrity will be capable to judge what is good and act accordingly without being extrinsically rewarded, or without having to be coerced into turning away from whatever is not virtuous. If moral equality for all men were recognized (which is the basic moral assumption of democracy), than instilling values into children or students should also be considered morally unacceptable. Namely, treating humans as means instead as ends in themselves, violates the moral autonomy of the person. Aims in education should always be reconsidered, since extensive knowledge in a civic cultural system ought to be accessible to all humans. Although the concept of training might be valuable, as it is an empirical concept it seems to be insufficient to qualify a person for any autonomous analytical assessment. In spite of the fact that views about the purpose of education differ widely, the typical reason why every stratified, or class system involves a huge amount of indoctrination is the need to preserve the political and economic power in the hands of the few. 31 Civic Culture - What It Is, Essay 1: The Cultural Creation of Citizens, http://www.civsoc.com/whatclt1.htm, pg. 2 of 4 32 Wilhelm von Humboldt: The Limits of State Action, pg. 7 33 Alan Harris: Thinking about Education, pg. 5 10 References Brown S. C. (editor) Philosophers Discuss Education, The Macmillan Press Ltd., London, 1975 Civic Culture - What It Is, Essay 1: The Cultural Creation of Citizens, http://www.civsoc.com/whatclt1.htm Cornford, Francis MacDonald: Plato's Theory of Knowledge – The Theaetetus and the Sophist of Plato, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, London, 1951 Harris, Alan: Thinking About Education, Heinemann Educational Books, London, 1970 Hill, Thomas E.: The Concept of Meaning, George Allen & Unwin, London, 1974 Hollins, T. H. B. (editor): Aims in Education – The Philosophic Approach, Manchester University Press, 1967 Langford, Glenn & O'Connor D. J. (editors): New Essays in the Philosophy of Education, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., London, 1973 Lipman, Matthew; Sharp, Ann Margaret; Oscanyan, Frederick, S.: Philosophy in the Classroom, Published for The Institute For Children, Montclair State College, Upper Montclair, New Jersey, 1977 Natale, Samuel M: Ethics and Morals in Business, REP, Birmingham, Alabama, 1983 Peters, R. S. (editor): The Concept of Education, (Contributors: R. S. Peters; D. W. Hamlyn; Paul H. Hirst; G. Vesey; R. F. Dearden; Max Black; Gilbert Ryle; Israel Scheffler; Michael Oakeshott; J. P. White; John Passmore), Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1967 Plato: Laws, translated by T. J. Saunders, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1953 Rich, John Martin (editor): Readings in the Philosophy of Education, Second Edition, Wadsworth Publishing Company, Inc., Belmont, California, 1972 Silverman, Sharon L. & Casazza; Martha E.: Learning & Development – Making Connections to Enhance Teaching, Jossey- Bass Publishers, San Francisco, 1999 Sternberg, Elaine: Just Business – Business Ethics in Action, Second Edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2000 The Basic Works of Aristotle, Edited and with an Introduction by Richard McKeon, Random House, New York, 1968 The Domain of Moral Education, Edited by D. B. Cochrane; C. M. Hamm; A. C. Kazepides, Paulist Press Ramsey, New York 1979 Theories of Ethics, Edited by Philippa Foot, Oxford Readings in Philosophy, Oxford University Press, Glasgow 1967 Wilson, John: Preface to the Philosophy of Education, International Library of the Philosophy of Education, General Editor R. S. Peters, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., London, 1979 11