Schuman

advertisement

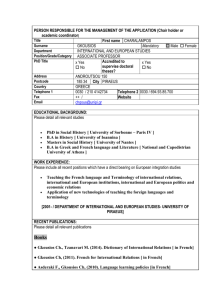

9th May 1950 THE SCHUMAN DECLARATION Jean Monnet & Robert Schuman 9th May 2003 2 I. THE SCHUMAN DECLARATION: A POLITICAL INITIATIVE WITH A SPIRITUAL VALUE Europe at the service of peace and democracy On 9 May 1950, Robert Schuman made history by putting to the Federal Republic of Germany, and to the other European countries who so wished, the idea of creating a Community of pacific interests. In so doing he extended a hand to yesterday's enemies and erased the bitterness of war and the burden of the past. In addition, he set in train a completely new process in international relations by proposing to old nations to together recover, by exercising jointly their sovereignty, the influence which each of them was incapable of exercising alone. The construction of Europe has since then moved forward every day. It represents the most significant undertaking of the 20th century and a new hope at the dawn of the new century. It derives its momentum from the far-sighted and ambitious project of the founding fathers who emerged from the second world war driven by the resolve to establish between the peoples of Europe the conditions for a lasting peace. This momentum is regenerated unceasingly, spurred on by the challenges which our countries have to face up to in a world of deep-seated and relentless change. Could anyone have foreseen this immense desire for democracy and peace which ultimately brought down the Berlin Wall, put the responsibility for their destinies back into the hands of the people of central and eastern Europe and today, with the prospect before long of further enlargement to seal the unity of the continent, gives a new dimension to the ideal of European construction? A historic success As we approach the dawn of the third millennium, a look back over the 50 years of progress towards European integration shows that the European Union is a historic success. Countries which were hitherto enemies, and in most cases, ravaged by the most horrific atrocities this continent has ever known, today share a common currency, the euro, and manage their economic and commercial interests within the framework of joint institutions. Europeans now settle their differences through peaceful means, applying the rule of law and seeking conciliation. The spirit of superiority and discrimination has been banished from relationships between the Member States, which have entrusted to the four Community institutions, the Council, the Parliament, Commission and the Court of Justice, the responsibility for mediating their 3 conflicts, for defining the general interest of Europeans and for pursuing common policies. People's standard of living has improved considerably, much more than would have been possible if each national economy had not been able to benefit from the economies of scale and the gains of growth stemming from the common market and intensification of trade. People are free to move and students to work within a frontier-free internal area. The foundations of common foreign and defence policies have been laid, and moves are already afoot to take common policies of solidarity further in the social, regional and environmental fields, as well as in the fields of research and transport. The European Community derives its strength from common values of democracy and human rights, which rally its peoples, and it has preserved the diversity of cultures and languages and the traditions which make it what it is. The European Community stands as a beacon for the expectations of countries near and far which watch the Union's progress with interest as they seek to consolidate their re-emerging democracies or rebuild a ruined economy. From I May 2004, the Union will have 25 Member. Other countries of former Yugoslavia, or which belong to the European sphere, are in turn asking to join. For the first time in its long history, the continent is preparing to become reunified in peace and freedom. Such developments are momentous in terms of world balance and will have a huge impact on Europe's relations with the United States, Russia, Asia and Latin America. Even now Europe is no longer merely a power which has retained its place in the world. It is a reference point and a hope for peoples attached to peace and the respect of human rights. What explains such a great success? Is it lastingly etched in the continent's history, sufficiently rooted in the collective memory and resolve for the seeds of any intraEuropean war to have been eradicated? The tragic events of the past and the conflicts which still today undermine the planet should prompt Europeans not to sit back and take lasting peace for granted. The challenges of the future After a half century of Community history, Europeans still have a lot of soulsearching to do: what are the elementary values to which they are attached, and what are the best ways of safeguarding them? How far could and should union be taken in order to maximise the strength which derives from unity, without at the same time eroding identity and destroying the individual ethos which makes the 4 richness of our nations, regions and cultures? Can we move forward in step, thanks to the natural harmony which favours consensus between 25 countries, or should we recognise divergences of approach and differentiate our pace of integration? What are the limits of Community Europe, at a time when so many nations are asking to join the process of unification in progress? How can we get everyone involved in the Community undertaking and give them the feeling of a European identity which complements and goes beyond fundamental solidarity? How can we get every European citizen closer to the institutions of the Union, and give everyone a chance to embrace the project of a unified Europe which was long the preserve of the deliberations of diplomats and the expertise of civil servants? The topicality of the Community method Since 2002, the Convention on the Future of Europe has been drafting a Constitution for the Union. Hopes are running at the same level as the ambitions and challenges involved, but the risks of failure are still very much there. Europe merely as a free trade area or Europe as a world-level player? A technocratic Europe or a democratic Europe? An 'every man for himself' Europe or a caring Europe? Faced with so many critical choices, so many uncertainties, the Community method which stems from the dialogue established between the Member States and the common institutions exercising together delegated sovereignty is as topical as ever. This is what made it possible, 50 years ago, to set up the European Community. The founding principles of the European edifice are not simply a matter of institutional mechanics. The Community spirit was invented and carried forward by statesmen who wanted first and foremost to construct a Europe at the service of people and makes the European idea a project for civilisation. The Schuman declaration remains very much 'a new idea for Europe'. 5 II. THE SCHUMAN DECLARATION: THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The respite which should have followed the cessation of hostilities did not materialise for the people of Europe. No sooner had the Second World War ended than the threat of a third between East and West loomed up very quickly. The breakdown on 24 April 1947 of the Moscow conference on the German issue convinced the West that the Soviet Union, an ally in the fight against the Nazis, was about to become the source of an immediate threat to western democracies. The creation in October 1947 of the Kominform establishing a coalition of the world's communist parties, the 'Prague coup' of 25 February 1948 guaranteeing domination for the communists in Czechoslovakia, then the Berlin blockade in June 1948 which heralded the division of Germany into two countries, further heightened tension. By signing the Atlantic Pact with the United States on 4 April 1949, western Europe laid the basis of its collective security. However, the explosion of the first Soviet atomic bomb in September 1949 and the proliferation of threats from the Kremlin leaders contributed to spreading this climate of fear which came to be known as the cold war. The status of the Federal Republic of Germany, which itself directed its own internal policy since the promulgation of the fundamental law of 23 May 1949, then became a focal point of East-West rivalry. The United States wanted to step up the economic recovery of a country at the heart of the division of the continent and already in Washington there was a call in some quarters for the defeated power to be re-armed. French diplomacy was torn by a dilemma. Either it yielded to American pressure and, in the face of public opinion, agreed to the reconstitution of the German power on the Ruhr and the Saar; or else it stood firm against its main ally and took its relationship with Bonn into an impasse. In spring 1950 came the hour of truth. Robert Schuman, French Foreign Affairs Minister, had been entrusted by his American and British counterparts with a vital mission, namely to make a proposal to bring Federal Germany back into the western fold. A meeting between the three governments was scheduled for 10 May 1950 and France could not evade its responsibilities. On top of the political deadlock came economic problems. Steelmaking capacity in the various European countries seemed set to create a crisis of overproduction. Demand was dwindling, prices were falling and the signs were that producers, faithful to the traditions of the forgemasters of the inter-war period, would reconstitute a cartel in order to restrict competition. In the midst of the reconstruction phase, the European economies could not stand by and leave their basic industries to speculation or organised shortages. 6 Jean Monnet's ideas In order to unravel this web of difficulties where traditional diplomacy was proving powerless, Robert Schuman called upon the inventive genious of a man as yet unknown to the general public but who had acquired exceptional experience during a very long and eventful international career. Jean Monnet, at the time responsible for the French modernisation plan and appointed by Charles de Gaulle in 1945 to put the country back on its economic feet, was one of the most influential Europeans in the western world. Jean Monnet and Robert Schuman During the First World War, he had organised the joint supply structures for the Allied Forces. Deputy Secretary-General of the League of Nations, banker in the United States, western Europe and China, he was one of President Roosevelt's close advisers and the architect of the Victory programme which ensured America's military superiority over the Axis forces. Unfettered by any political mandate, he advised governments and had acquired the reputation of being a pragmatist whose prime concern was effectiveness. The French Minister had approached Jean Monnet with his concerns. The question 'What to do about Germany?' was an obsession for Robert Schuman, a native of Lorraine and a Christian moved by the resolve to do something so that any possibility of further war between the two countries could be averted once and for all. At the head of a small team in rue de Martignac, headquarters of the Commissariat au plan, Jean Monnet was himself committed to this quest for a solution. His main concern was international politics. He felt that the cold war was the consequence of competition between the two big powers in Europe and a divided Europe was a source of major concern. Fostering unity in Europe would reduce tension. He pondered the merits of an international-level initiative mainly designed to decompress the situation and establish world peace through a real role played by a reborn, reconciled Europe. Jean Monnet had watched the various unsuccessful attempts to move towards integration which had followed in the wake of the solemn plea, launched at the congress organised by the European movement in The Hague in 1948, for the union of the continent. The European Organisation for Economic Cooperation, set up in 1948, had a purely coordinative mission and had been powerless to prevent the economic recovery of European countries coming about in a strictly national framework. The creation of the Council of Europe on 5 May 1949 showed that governments were not prepared to surrender their prerogatives. The advisory body had only deliberative powers and each of its resolutions, which had to be approved by a two-thirds majority, could be vetoed by the ministerial committee. 7 Jean Monnet had understood that any attempt to introduce a comprehensive institutional structure in one go would bring a huge outcry from the different countries and was doomed to failure. It was too early yet to envisage wholesale transfers of sovereignty. The war was too recent an experience in people's minds and national feelings were still running very high. Success depended on limiting objectives to specific areas, with a major psychological impact, and introducing a joint decision-making mechanism which would gradually be given additional responsibilities. The declaration of 9 May 1950 Jean Monnet and his co-workers during the close of April 1950 drafted a note of a few pages setting out both the rationale behind, and the steps envisaged in, a proposal which was going to radically shake up traditional diplomacy. As he set about his task, instead of the customary consultations of the responsible ministerial departments, Jean Monnet on the contrary maintained the utmost discretion in order to avoid the inevitable objections or counterproposals which would have detracted from the revolutionary nature of the project and removed the advantage of surprise. When he handed over his document to Bernard Clappier, director of Robert Schuman's private office, Jean Monnet knew that the minister's decision could alter the course of events. So when, upon his return from a weekend in his native Lorraine, Robert Schuman told his colleagues: 'I've read this proposal. I'll use it', the initiative had entered the political arena. At the same time as the French Minister was defending his proposal on the morning of 9 May, in front of his government colleagues, a messenger from his private office delivered it personally to Chancellor Adenauer in Bonn. The latter's reaction was immediate and enthusiastic. He immediately replied that he was wholeheartedly behind the proposal. So, backed by the agreement of both the French and the German Governments, Robert Schuman made his declaration public at a press conference held at 4 p.m. in the salon de l'Horloge at the Quai d'Orsay. He preceded his declaration with a few introductory sentences: 'It is no longer a time for vain words, but for a bold, constructive act. France has acted, and the consequences of her action may be immense. We hope they will. She has acted essentially in the cause of peace. For peace to have a chance, there must first be a Europe. Nearly five years to the day after the unconditional surrender of Germany, France is now taking the first decisive step towards the construction of Europe and is associating Germany in this venture. It is something which must completely change things in Europe and permit other joint actions which were hitherto impossible. Out of all this will come forth Europe, a solid and united Europe. A Europe in which the standard of living will rise thanks to the grouping of production and the expansion of markets, which will bring down prices ...' 8 The scene was thus set. This was no new technical arrangement subject to fierce bargaining. France extended a hand to Germany, proposing that it take part on an equal footing in a new entity, first to manage jointly coal and steel in the two countries, but also on a broader level to lay the first stone of the European federation. The declaration puts forward a number of principles: - Europe will not be made all at once, or according to a single plan. It will be built through practical achievements which will first create real solidarity; - the age-old enmity between France and Germany must be eliminated; any action taken must in the first place concern these two countries, but it is open to any other European nations which share the aims; - action must be taken immediately on one limited but decisive point: FrancoGerman production of coal and steel must be placed under a common High Authority; - the fusion of these economic interests will help to raise the standard of living and establish a European Community; - the decisions of the High Authority will be binding on the member countries. The High Authority itself will be composed of independent persons and have equal representation. The authority's decisions will be enforceable. The preparation of the ECSC Treaty Swift action was needed for the French initiative, which quickly became a FrancoGerman initiative, to retain its chances of becoming reality. On 20 June 1950, France convened an intergovernmental conference in Paris, chaired by Jean Monnet. The three Benelux countries and Italy answered the call and were at the negotiating table. Jean Monnet circumscribed the spirit of the discussions which were about to open: 'We are here to undertake a common task - not to negotiate for our own national advantage, but to seek it to the advantage of all. Only if we eliminate from our debates any particularist feelings shall we reach a solution. In so far as we, gathered here, can change our methods, the attitude of all Europeans will likewise gradually change' 1. The discussions were an opportunity to clarify the type of international edifice envisaged. The independence and the powers of the High Authority were never questioned, for they constituted the central point of the proposal. At the request of the Netherlands, the Council of Ministers, representing the Member States and which was to give its assent in certain cases, was set up. A Parliamentary Assembly 1 Jean Monnet, Memoirs, (trad. R. Mayne): London, etc., William Collins and Son Ltd, 1976, p. 323. 9 and a Court of Justice were to round off the structure which underpins the institutional system of the current Communities. The negotiators never lost sight of the fact that they had the political mandate to construct an organisation which was totally new with regard to its objectives and methods. It was essential for the emerging institution to avoid all the shortcomings peculiar to the traditional intergovernmental organisations: the requirement of unanimity for national financial contributions, and subordination of the executive to the representatives of the national States. On 18 April 1951, the Treaty establishing the Coal and Steel Community was signed for a period of 50 years. It was ratified by the six signatory countries and on 10 August 1952 the High Authority, chaired by Jean Monnet, took up its seat in Luxembourg. 10 III. THE SCHUMAN PLAN: THE BIRTH OF COMMUNITY EUROPE 'The Schuman proposals are revolutionary or they are nothing. The indispensable first principle of these proposals is the abnegation of sovereignty in a limited but decisive field. A plan which is not based on this principle can make no useful contribution to the solution of the major problems which undermine our existence. Cooperation between nations, while essential, cannot alone meet our problem. What must be sought is a fusion of the interests of the European peoples and not merely another effort to maintain the equilibrium of those interests ...' Jean Monnet The innovatory principles of the first European Community The reason it took nearly a year to conclude the negotiations of the Treaty of Paris was that these negotiations gave rise to a series of fundamental questions to which Jean Monnet wished to provide the most appropriate answers. As we have seen, this was no traditional diplomatic negotiation. The persons designated by the six governments had come together to invent a totally new - and lasting - legal and political system. The preamble to the ECSC Treaty, comprising five short paragraphs, contains the whole philosophy which was to be the leitmotif of the promoters of European construction: - 'Considering that world peace can be safeguarded only by creative efforts commensurate with the dangers that threaten it; - convinced that the contribution which an organised and vital Europe can make to civilisation is indispensable to the maintenance of peaceful relations; - recognising that Europe can be built only through practical achievements which will first of all create real solidarity, and through the establishment of common bases for economic development; - anxious to help, by expanding their basic production, to raise the standard of living and further the works of peace; - resolved to substitute for age-old rivalries the merging of their essential interests; to create, by establishing an economic community, the basis for a broader and deeper community among peoples long divided by bloody conflicts; and to lay the foundations for institutions which will give direction to a destiny henceforward shared'. 11 'World peace', 'practical achievements', 'real solidarity', 'merging of essential interests', 'community', 'destiny henceforward shared': these are all key words which are the embryonic form of both the spirit and the Community method and still today retain their rallying potential. While the prime objective of the ECSC Treaty, i.e. the management of the coal and steel market, today no longer has the same importance as before, for the European economy of the 1950s, the institutional principles which it laid down are still very much topical. They started a momentum of which we are still reaping the benefits and which fuels a political vision which we must be careful not to depart from if we are not to call into question our precious 'acquis communautaire'. Stemming from the Schuman plan, four Community principles can be identified as forming the basis of the current Community edifice. The overarching role of the institutions The application to international relations of the principles of equality, arbitration and conciliation which are in force within democracies is progress for civilisation. The founding fathers had experienced the chaos, violence and the arbitrary which are the companions of war. Their entire endeavour was geared at creating a community in which right prevailed over might. Jean Monnet often quoted the Swiss philosopher Amiel: 'Every man's experience is a new start. Only institutions become wiser: they amass the collective experience and thanks to this experience and this wisdom, the nature of men subordinated to the same rules will not change, but their behaviour gradually will.' To place relations between countries on a pacific and democratic footing, casting out the spirit of domination and nationalism, these were the deep-seated motivations which gave the first Community its political content and placed it amongst the major historic achievements. The independence of the Community bodies If institutions are to fulfil their functions they must have their own authority. Today's Community institutions still benefit from the three guarantees which were given to the ECSC High Authority: the appointment of members, today commissioners, by joint agreement between the governments2. These are not national delegates, but personalities exercising their power collegially and who may not receive instructions from the Member States. The European civil service is subordinated to this same and unique Community allegiance; The European Commission is also subordinated to the vote of investiture by the European Parliament. 2 12 financial independence through the levying of own resources and not, as is the case of international organisations, by the payment of national contributions which means they can be called into question; the responsibility of the High Authority, and today that of the Commission, exclusively to the Assembly (today the European Parliament), which can cast, by a qualified majority vote, a vote of censure. Cooperation between the institutions For Jean Monnet, the independence of the High Authority was the cornerstone of the new system. However, as the negotiations continued, he acknowledged the need to give the Member States the opportunity to assert their national interests. This was the safest way of preventing the emerging community from being limited to excessively technical objectives, for it needed to be also able to intervene in sectors in which macroeconomic decisions would be taken and these were a matter for the governments. Hence the creation, alongside the High Authority, of our Council of Ministers the role of which was strictly limited in that it was not called upon to decide unanimously but by majority. Its assent was required only in limited cases. The High Authority retained the monopoly of legislative initiative, a prerogative which, extended to the competences of the present Commission, is essential in that it is the guarantee that all Community interests will be defended in a proposal from the college. From 1951 on, dialogue was organised between the four institutions on a basis not of subordination but of cooperation, each institution exercising its own functions within a comprehensive decision-making system of a pre-federal type. Equality between Member States As the principle of representation of States within the Council had been selected, there remained the delicate matter of their respective weighting. The Benelux countries and Italy, fearing that they would be placed in a minority situation on account of the proportion of their production of coal and steel in relation to total production, argued in favour of the rule of unanimity. Germany, on the other hand, advocated a system of representation proportional to production, a proposal which of course could hardly allay partners' misgivings, quite the opposite. Jean Monnet was convinced that only the principle of equality between countries could produce a new mentality. However, he was aware of how difficult it was to get six countries of unequal dimensions to forego the option of a veto. For the big countries in their relations with one another and for the smaller countries in their relations with the bigger countries '... Their innermost security lay in their power to say No, which is the privilege of national sovereignty' 3. The chairman of the 3 Jean Monnet, op. cit., pp. 330 et seq. 13 conference accordingly met Chancellor Adenauer in Bonn on 4 April 1951 to convince him of the virtues of the principle of equality: 'I have been authorised to propose to you that relations between France and Germany in the European Community be based on the principle of equality in the Council, the Assembly and all future or existing institutions ... Let me add that this is how I have always envisaged the offer of union which was the starting point of the present Treaty; and I think I am right in saying this is how you envisaged it from the moment we first met. The spirit of discrimination has been the cause of the world's greatest ills, and the Community is an attempt to overcome it'. The Chancellor replied immediately: 'You know how much I am attached to equality of rights for my country in the future, and how much I deplore the attempts at domination in which it has been involved in the past. I am happy to pledge my full support for your proposal. I cannot conceive of a Community based on anything but complete equality'. Thus was laid one of the legal and moral foundations which gives the notion of Community its full meaning. The ECSC, the first stone in the European edifice In the absence of a peace treaty between the former warring sides, the first European Community was both an act of confidence in the resolve of France and Germany and their partners to sublimate the mistakes of the past and perform an act of faith in a common future of progress. Despite the ups and downs of history and of nationalist opposition, the process began in 1950 was never to stop. 14 IV. THE IDEAS OF JEAN MONNET AND ROBERT SCHUMAN QUOTATIONS: JEAN MONNET EQUALITY/NON DISCRIMINATION 'The fault layed in the Treay of Versailles: it was based on discrimination. From the moment I first began to be concerned with public affairs I have always realized that equality is absolutely essential in relations between nations, as it is between people. A peace based on inequality could have no good results.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Dubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part One, Chapter 4, p. 97, 2nd paragraph. 'If the countries of Europe once more protect themselves against each other, it will once more be necessary to build up vast armies. Some countries, under the future peace treaty, will be able to do so; to others it will forbidden. We experienced such discrimination in 1919; we know the results. Alliances will be concluded between European countries, we know how much they are worth. [...] Europe will be reborn yet again under the shadow of fear. Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 9 p. 222, 2nd paragraph. 'Peace can be founded only on equality. We failed in 1919 because we introduced discrimination and a sense of superiority.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 11 p. 284, 2nd paragraph. Meeting with R.Schuman. 15 'A solution which would put French industry on the same footing as German industry, while freeing the latter from the discrimination born of defeat would restore the economic and political preconditions for the mutual understanding so vital to Europe. It could, in fact, become the germ of European unity.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 12 p. 292293, last paragraph. 'If the problem of sovereignty were approached with no desire to dominate or to take revenge, if on the contrary the victors and the vanquished agreed to exercise joint sovereignty over part of their joint resources, then, a solid link would be forged between them, the way would be wide open for further collective action, and a great example would be given to the other nations of Europe.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 12 p. 293, 2nd paragraph. 'The spirit of domination has been the cause of the world's greatest ills, and the Community is an attempt to overcome it.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday&Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 14 p. 354, 3rd paragraph. Meeting with K.Adenauer, April, 4 1951. 'It cannot all be done at once: it is gradually that we shall achieve this organization. But already it is essential to make a start. It is not a question of solving political problems which, as in the past, divide the forces that seek domination or superiority. Its is a question of inducing civilization to make fresher progress, by beginning to change the form of the relationship between countries and applying the principle of equality between peoples and between countries.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 20 p. 487, 3rd paragraph. Notes, August, 22 1966. ‘To start unifying Europe five years after the last war, it was essential for everyone to understand that there were no longer the victors and the defeated, but only equal partners under a common law.’ Source: ‘Europe-America: a necessary partnership for peace’ Speech by Jean Monnet at the award ceremony for the ‘Freedom prize’, New York, 23 January 1963. Centre for European Research, Lausanne, April 1963 16 ‘The common market was not set up simply to establish a better system of trade in goods, nor to create a new power. Our main objective was, and still is, to create a unified Europe and remove the spirit of domination from relations between countries and their peoples, which has several times brought the world close to destruction.’ Source: ‘Europe-America: a necessary partnership for peace’ Speech by Jean Monnet at the award ceremony for the ‘Freedom prize’, New York, 23 January 1963. Centre for European Research, Lausanne, April 1963 PEACE 'There will be no peace in Europe if States re-establish themselves on the basis of national sovereignty, with that this implies by way of prestige policies and economic protectionism.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 9, p. 222, 2nd paragraph. Note written for the Committee of National Liberation in Algiers on August 5, 1943. 'Coal and steel were at once the key to economic power and the raw materials for forging weapons of war. This double role gave them immense symbolic significance, now largely forgotten, but comparable at the time to that of nuclear energy today. To pool them across frontiers would reduce their malign prestige and turn them instead into a guarantee of peace.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 12 p. 293, 3rd paragraph. 'The best contribution one can make to civilization is to allow men to develop their potential within communities freely chosen and built'. Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 14, p. 356, 4th paragraph 17 'Like all political systems, the Community cannot prevent problems arising; but it offers a framework and a means for solving them peacefully. This is a fundamental change by comparison with the past - the very recent past.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 15, p. 390, 1st paragraph. ‘Today, peace is not only a matter of treaties or commitments. It depends essentially on creating conditions which, though they may not change human nature, guide people’s behaviour towards each other in a peaceful direction. This is one of the essential consequences of the transformation of Europe which is our Community’s aim. By achieving unity, by restoring vitality to Europe, by creating new conditions which will last, the Europeans are contributing to peace.’ Source: Jean Monnet, ‘Pointers for a method, thoughts on the construction of Europe’, Fayard 1996, p. 106. Speech, Washington, 30 April 1952 - ‘Making Europe is making peace.’ Source: Jean Monnet, ‘Pointers for a method, thoughts on the construction of Europe’, Fayard 1996, p. 108. Speech, Aix-laChapelle, 17 May 1953 ‘The United States of Europe are not only the great hope but also the urgent need of our era, because they will bring about the full development of each of our peoples and the consolidation of peace.’ Source: Jean Monnet, ‘Pointers for a method, thoughts on the construction of Europe’, Fayard 1996, p. 108. WORKING FOR MANKIND - 'We are not forming coalitions between States, but union among people.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Introduction. 18 'The countries of Europe are too small to give their peoples the prosperity that is now attainable and therefore necessary. They need wider markets... To enjoy the prosperity and social pogress that are essential, the States of Europe must form a federation or a 'European entity' which will make them a single economic unit.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 9, p. 222, 2nd paragraph. 'We want to put Franco-German relations on an entirely new footing. We want to turn what divided France from Germany, that is the industries of war, into a common asset, which will also be European. In this way, Europe will rediscover the leading role which she used to play in the wold and which she lost because she was divided. Europe's unity will not put an end to her diversity, quite the reverse. That rich diversity will benefit civilization and influence the evolution of powers like America itself. The aim of the French proposal, tehrefore, is essentially political. It even has an aspect which might be called moral.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 12, p. 309310, last paragraph. Meeting with K.Adenauer, 1950. 'Men who are placed in new practical circumstances, or subjected to a new set of obligations, adapt their behaviour and become different. If the new context is better, they themselves become better: that is the whole rationale of the European Community, and the process of civilization itself.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 15, p. 389390, last paragraph. 'Major psychological changes, which some seek through violent revolution, can be achieved very peacefully if men's minds can be directed towards the point where their interests converge. That point always exists: but it takes trouble to find it.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 15, p. 392, 1st paragraph. 19 'Our Community is not a coal and steel poducers' association: it is the beginning of Europe. The beginning of Europe was a political conception; but even more, it was a moral idea.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 15, p. 392, 1st and 2nd paragraphs. 'When I think that Frenchmen, Germans, Belgians, Dutchmen, Italians, and Luxembourgers are obeying the same rules and, by doing so, are now seeing their common problems in the same light; when i reflect that this will fundamentally change their behaviour one to another - then I tell myself that definitive pogress is being made in relations among the countries and people of Europe.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 15, p. 393, 2nd paragraph. Speech at the Assembly of the ECSC, 1954. 'Our countries have become too small for the present-day world, for the scale of modern technology and of America and Russia today, or China and India tomorrow. The union of European peoples in the United States of Europe is the way to raise their standard of living and preserve peace. It is the great hope and opportunity of our time.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 15, p. 399400, last paragraph. Meeting with the members of the High Authority of the ECSC on November, 9 1954. 'It must be understood that the Common Market is a process of change - not only economic change, but psychological change as well.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 18, p. 460, 1st paragraph. Meeting with a newspaperman, July 1963. 'What we had achieved in Europe, against all expectations, ought equally to be possible wherever men were still thinking in terms of domination and hoping to settle their dispute by force. I was convinced that the union of Europe was not only important for the Europeans themselves: it was valuable as an example for others, and this was a further reason for bringing it about.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 21, p. 511, 1st paragraph. 20 ‘The greatest danger that Europe runs is the impoverishment of the individual, through being unable to apply to his daily life and his security the means that progress would allow him to apply. If he cannot do so, it is because the conditions under which we live, the conditions in which the countries of Europe live, prevent him.’ Source: Jean Monnet, ‘Pointers for a method, thoughts on the construction of Europe’, Fayard 1996, pp. 82-83 INSTITUTIONS/SUPRANATIONALITY/GENERAL INTEREST 'All too often I have come up against the limits of mere coordination: it makes for discussion, but not decision. In circumstances where union is necessary, it fails to change relations between men and between countries. It is the expression of national power, not a means of transforming it: that way, unity will never be achieved.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part One, Chapter 1, p. 35, 1st paragraph. 'Co-operation between nations will grow from their getting to know each other better, and from interpenatration between their constituent elements and those of their neighbours. It is therefore important to make both Goverments and peoples know each other better, so that they come to see the poblems that face them not from the viewpoint of their own interests, but in the light of the general interest. Without a doubt, the selfishness of men and of nations is most often caused by inadequate understanding of the problem in hand, each tending to see only that aspect of it which affects his immediate interests.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part One, Chapter 4, p.83, 3rd paragraph. 'Bringing Governments together, getting national officials to cooperate, is well-intentionned enough; but the method breaks down as soon as national interests conflict, unless there is an independent political body that can take a common view of the problem and arrive at a common decision.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part One, Chapter 4, p. 87, 1st paragraph. 21 'The veto was at once the cause and the symbol of this inability to go beyond national self-interest. But it was no more than the expression of much deeper deadlocks, often unacknowledged.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part One, Chapter 4, p. 97, 2nd paragraph. 'It would be a mistake to ask more than that of a system which entailed no delegation of sovereignty. Very soon, OEEC had become simply technical machinery; but it outlived the Marshall Plan because it provided a mass of information which everyone found useful. I realized that neither this organization, with its headquarters at the Château de la Muette in Paris, nor the parlimentary meetings in Strasbourg that resulted from the Hague Congress, would ever give concrete expression to European unity. Amid these vast groupings of countries, the common interest was too indistinct, and common disciplines were too lax. A start would have to be made by doing something both more practical and more ambitious. National sovereignty would have to be tackled more boldly and on a narrower front.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 11, p. 273274. 'I had already learned this from my experience at the League of Nations; but apparently no one remembered the vetos that had blocked all our efforts to find peaceful solutions to the conflicts set off by Japan, Italy, and Germany. The United Nations Organization had the same inbuilt flaw, and so had the Council of Europe. [...] The international assemblies gave themselves the appearance of democratic bodies, publicly expressing their people's will: what was less obvious was that even their unanimous resolutions were nullified, behind their backs, by a Committee or Council of Government representatives, any one of whom could prevent all the others from acting as they wished.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 11, p. 281, 3rd paragraph 'Nothing is possible without men: nothing is lasting without institutions.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 12, p. 304305. 22 'The Schuman proposals are revolutionary or they are nothing. Co-operation between nations, while essential, cannot alone meet our problem. What must be sought is a fusion of the interests of the European peoples and not merely another affort to maintain an equilibrium of those interests through additional machinery for negotiation.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 12, p. 316, 1st paragraph. 'Since these institutions were set up, the Europe we want to bequeath to our children has begun to be a living reality.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 15, p. 383, 3rd paragraph. 'Europe, that is, would be built by the same process as each of our national States by establishing among nations a new relationship comparable to that which exists among the citizens of any democratic country: equality, oganized by common institutions.' [...]'The union of Europe cannot be based on goodwill alone. Rules are needed. The tragic events we have lived through and are still witnessing may have made us wiser. But men pass away; others will take our place. We cannot bequeath them our personal experience. That will die with us. But we can leave them institutions. The life of institutions is longer than that of men: if they are well built, they can accumulate and hand on the wisdom of succeeding generations.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 15, p. 383384, last paragraph. Speech at the Assembly of the ESCC, 1952. 'If Europe has been pulled in many different directions by people with contrasting ideas of her destiny, I regard that as a great waste of time and effort, but no denial of the need to unite. It was simply that ideas and methods differed; and as always, reality had the last word. Today, I believe, reality is having the last word again - and it closely ressembles the first, written in 1950. What it spells is the delegation of sovereignty and the joint exercice of the new and larger sovereignty thus created. I cannot see that in twenty-five years anything else has been invented as a means of uniting Europe, despite all the temptations to desert that path.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 17, p. 432, 1st paragraph. 23 'The search for common interest, [...] by no means excludes taking account of the other's point of view; but it must no turn into haggling. We held fast to our method, which consists in determining what is good for all the Community countries as a whole, then taking the measure of the particular efforts which will have to make - but without vainly seeking, as in the past, a meticulous balance of advantage.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 17, p. 435, 2nd paragraph. 'There's a fundamental difference between the Community, which is a way of uniting peoples, and the Free Trade Area, which is symply a commercial arrangement. Our institutions take an overall view and propose common policies; the Free Trade Area poject is an attempt to solve particular poblems without putting them in the context of colective action.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 18, p. 449, 2nd paragraph. Meeting with L.Herhard, January 1969. 'To persuade people to talk together is the most one can do to serve the cause of peace. But for this a number of conditions must be fulfilled, all equally important. One is that the talks be conducted in a spirit of equality, and that no one should come to the table with the desire to score off somebody else. That means abandoning the supposed privileges of sovereignty and the sharp weapon of veto. The second condition is that everyone should talk about the same thing; the third, finally, is that everyone should seek the interest which is common to them all. This method does not come naturally to people who meet to deal with poblems that have arisen precisely because of the conflicting interests of nation-States. They have to be induced to understand the method and apply it. Experience has taught me that for this purpose goodwill is not enough, and that a certain moral power has to be imposed on everyone - the power of rules laid down by common institutions which are greater than individuals and are respected by States. Those institutions are designed to promote unity complete unity where there is likness, and harmony where differences still exist.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part Two, Chapter 19, p. 474475, last paragraph. 24 SOLIDARITY 'Even where solidarity is obviously essential, it still does not come naturally. It needs organization. That organiszation is never complete.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part One, Chapter 7, p.176, last paragraph. MUTUAL CONFIDENCE [Mutual confidence] 'grows up naturally between men who take a common view of the problem to be solved. When the problem becomes the same for everyone, and they all have the same concern to solve it, then differences and suspicions disappear, and friendship very often takes their places.' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978. Part One, Chapter 3, p.76, last paragraph 25 QUOTATIONS: ROBERT SCHUMAN FRATERNITY 'For many years we have suffered from an ideological demarcation line which is splitting Europe apart. It was imposed by violence. Let it be wiped out in freedom!' [...] 'We consider all those who wish to join us in our re-formed community to be an integral part of this living entity of Europe. We pay homage to their courage and loyalty and also to their suffering and sacrifices. We owe them the example of a united and fraternal Europe.' [...] 'The European community must create an atmosphere of mutual understanding which respects the particular characteristics of each party; it will form the solid basis of a fruitful and peaceful cooperation. In this way a new, prosperous and independent Europe will come about. Our duty is to be ready for it.' Source: Robert Schuman Revue France-Forum No. 52, November 1963. 'It is no longer possible for any thinking European to take a Machiavellian pleasure in the misfortunes of his neighbour; we are all united, for better or for worse, in a community of destiny.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 43. 26 SOLIDARITY 'Over and above the institutions, and reflecting a deeply held aspiration in our peoples, the European idea, the spirit of solidarity and community, has taken root.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 16-17. 'Our borders in Europe must become much less of a barrier to the exchange of ideas, persons and goods. A sense of solidarity among nations will triumph over outmoded forms of nationalism.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe'. [For Europe] Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 23. 'This Europe is not directed against anyone; it has no designs of aggression, no egotistical or imperialist nature, either internally or with regard to other countries. It will remain accessible to those wishing to join. Its raison d’être is solidarity and international cooperation, a rational organisation of the world of which it must form an essential part.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 25. 'It is necessary for everyone to share this conviction of needing one another, regardless of the status and power we possess.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 26-27. 'After two world wars we have come to realise that the best guarantee for nations no longer lies in our splendid isolation, nor in our own strength, no matter how powerful we are, but in solidarity between nations, guided by the same spirit and ready to carry out common tasks, in the common interest.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 30. [Borders] 'retain their raison d'être if they are capable of changing their role to become more of a mental construct. Instead of 27 being barriers which separate they must become contact points where material and cultural exchanges are organised and developed; they will define the particular tasks for each country, its particular responsibilities and initiatives, when faced with all the problems affecting borders and even continents, so enabling all countries to show solidarity towards each other.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 34. 'Over and above being a military or economic alliance, Europe must be a cultural community in the highest sense.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 35. 'We do not, nor shall we ever deny our country or forget the duties which we owe it. But above each homeland we recognise with increasing clarity the existence of a common good, superior to the national interest, a good in which the individual interests of our countries will meet and merge.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 38. 'The law of solidarity between nations imposes itself on contemporary consciousness. We feel solidarity towards one a nother in our keeping of the peace, our defence against aggression, the fight against poverty, our respect for the treaties and in safeguarding justice and human dignity.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 38. 'We must bring people to accept European solutions, by fighting against not only any pretensions to hegemony or belief in superiority but also against any narrow-mindedness in political nationalism, any autarchic protectionism or cultural isolationism. All these tendencies which we have inherited from our past must be replaced by the concept of solidarity – a conviction that our real interest consists in each of us recognising and accepting that in practice we are all interdependent. Egotism will longer reward us.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 47. 28 'The surest way of protecting ourselves from the hazards of war and servitude is our collective cohesion in all matters economic, political and military. The close cooperation which will be established within the European communities which have already been created will encourage us to consider everything in terms of shared interest and responsibility. We will become accustomed to taking not only a strictly national point of view. [...] It will be necessary to begin with the national line but then place it within a framework in which all the national view-points will complement and perfect each other.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 149. 'Europeans will be saved to the extent that they are aware of their solidarity before a mutual threat.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 184. 'A real community assumes, at the least, a number of particular affinities. Countries do not join together unless they feel they have something in common and that must be, at the least, mutual trust. Likewise there must also be shared interests, without which there would be coexistence but not co-operation. In order to understand each other and build a close union, it is not necessary to give up our differences completely, but we must be sure that there are enough common links and ideas. Serving mankind is a duty demanded of us equal to that of national loyalty'. Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 196. 'Europe will not happen overnight, or as part of some grand design; it will come about in practical steps, building on a sense of common purpose.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. Appendix: The Declaration of 9 May 1950. 29 EQUALITY 'Europe will not be a sphere of influence to be exploited for the purposes of political, military, economic or any other type of domination. But in order to exist in reality it must be governed by the principle of equal rights and duties for all the countries involved.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 24-25. 'The European Community will not be made in the image of an empire or a holy alliance; it will be based on democratic equality, transposed to the arena of international relations.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 47. 'We cannot pretend that European integration is not an immense and arduous task, or that it has ever been attempted b efore. It requires a complete change in the relationships between European states, in particular between France and Germany. But this task is being undertaken together, on an absolutely equal basis, in mutual respect and trust, after a generation’s experience of intense suffering and hatred.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 106. 'It was up to her [France] to take the initiative and show a readiness to trust its neighbour, not by a platonic or conditional declaration but by the explicit offer of permanent cooperation in an area of such vital importance. In other words, France was proposing to deal with Germany on an equal footing.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 106-107. 30 PEACE 'Europe’s strength is its ability to contribute effectively and without delay, to the needs of mankind, in response to new aspirations among its nations. It is an enterprise for peace.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 25-26. 'War and its devastation, like the victory which brought liberation, have been collective enterprises. If we wish peace to be a lasting victory over war, it must be achieved together by all the nations, including those which yesterday were fighting each other and which are again in danger of falling into bloody rivalries.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 43-44. 'Yes, what is needed is something other than texts and words, something other than the stain of the crime that is war, something more than reminders of its horror and misery. War must be deprived of its raison d’être and the temptation to wage it removed. We must reach the point where no one, not even the least scrupulous of governments, has an interest in waging it. I will go further: we wish to remove the means of preparing for war, of taking the risk. The worst of gamblers will in future be rendered incapable of carrying out an attack. In place of the nationalism of old and of a defensive and suspicious independence, we shall join together the interests, decisions and destinies of this new community of previously rival states.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 45. 'So long as there is room for revenge, the hazards of war will reappear. A detailed settlement drawn up in private between conquerors and conquered may temporarily appease a territorial claim or conflict of prestige. But in itself it will never be sufficient to establish lasting peace. In the past there have been many attempts to stabilise political situations in regions of Europe by multilateral peace treaties.[…] We have gone from one disappointment to another because we failed to give these pseudo ententes something more than a somewhat artificial legal status, i.e. a common task and a new hope, capable of overcoming the past. This leads us today to look for a 31 common agreement, a form of peace which is not just an elimination of war but a blueprint for the future.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 108-109. 'But these approaches based on economics have also highlighted immediate advantages in the political arena. Concluding a lasting, monitored union in the area of coal and steel in effect prevents any of the countries involved not only from waging war against the others but even from preparing to do so, since one cannot go to war without free use of the energy and metals essential for such an undertaking.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 164. 'The contribution which an organised and living Europe can bring to civilisation is indispensable to the maintenance of peaceful relations. […] A united Europe was not achieved and we had war.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. Appendix: The Declaration of 9 May 1950. 'By pooling basic production and by instituting a new High Authority, whose decisions will bind France, Germany and other member countries, this proposal will lead to the realisation of the first concrete foundation of a European federation indispensable to the preservation of peace.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. Appendix: The Declaration of 9 May 1950. INSTITUTIONS 'The democratic law of the majority, freely accepted in accordance with established conditions and procedures, limited to the essential concerns of common interest, will certainly be less humiliating than decisions imposed by the strongest.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 25. 32 CHRISTIAN VALUES 'Here we are, then, constrained by experience, after so many failures of diplomacy or the generosity of certain individuals such as Aristide Briand, facing the terrible threats to mankind from the dizzying progress of proud science, here we are returning to the Christian law of a noble yet humble fraternity. And by a paradox which would surprise us if we were not Christians – unconsciously Christian perhaps – we hold out our hand to our enemies of yesterday, not simply in order to forgive them but to build tomorrow’s Europe together.’ Source: Robert Schuman ‘Pour l’Europe’ [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 44. 'This new policy is based on solidarity and building trust. It constitutes an act of faith, not like that of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, in the human kindness so cruelly denied for the last two centuries, but an act of faith in the good sense of nations at last persuaded that their salvation lies in entente and cooperation, so solidly cemented together that none of the governments involved could separate them. Let this concept of a reconciled, united and strong Europe become the slogan for the younger generations wishing to serve a mankind at last delivered from hatred and fear and which, after such long rifts, will teach us once more the concept of Christian fraternity. ' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 45-46. 'Europe is the implementation of a universal democracy in the Christian sense.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 53. 'Democracy owes its existence to Christianity. It was born the day when man was brought to recognise the dignity of the human being in his temporal life, in individual freedom, in respect for each other’s rights and by the practice of brotherly love towards all. Never before Christ had such ideas been expressed. Thus democracy is linked to Christianity, both in terms of doctrine and ideology. It took shape with it, gradually, after much trial and error, sometimes falling into serious mistakes and barbarism along the way.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 56-57. 33 'Christianity teaches the natural equality of all men, who are children of the same God, redeemed by the same Christ, without distinction of race, colour, class or profession. It makes us recognise the dignity of work which it is the obligation of us all to accept. It recognises the primacy of the inner values which alone lend nobility to man. The universal law of love and charity makes all people our neighbours, since when all social relationships in the Christian world have been based on this law.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 57-58. 'I agree with Bergson that "democracy is essentially evangelical in that its source is love".' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p.70. 'The implementation of this vast programme for a universal democracy in the Christian sense finds its fulfilment in the building of Europe.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 77. 'The Coal and Steel Community, Euratom and the Common Market, with the free circulation of goods, capital and persons, are institutions which are already profoundly and definitively changing relationships between associate states; in a certain sense they are becoming divisions, provinces of a single unit. And this unit cannot and must not remain a purely economic and technical enterprise: it requires a soul, an awareness of its historical affinities and its present and future responsibilities, a political will to serve the same human ideal.' Source: Robert Schuman 'Pour l'Europe' [For Europe]. Editions Nagel, Paris 1963. p. 77-78. 34 'Europe will be in difficulties for a very long time. Besides it's a fundamental error to think that one can make progress without difficulties.' [What has to be done?] 'Continue, continue, continue...' Source: Jean Monnet 'Mémoirs'. Doubleday & Company, INC. Garden City, New York. 1978.Part Two, Chapter 21, p.513, 3rd paragraph. 35 In charge of publication : Pascal FONTAINE Drafted by : Pascal FONTAINE and Leatitia DESCOIN, stagiaire OR : FR _____________________________________________ Research, Documentation and Publications service EPP-DE Group - European Parliament 47-53, rue Wiertz B-1047 BRUSSELS 36