The Kennedy Assassination and Media Coverage

advertisement

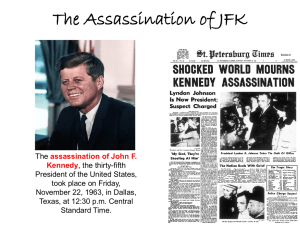

The Kennedy Assassination and Media Coverage Joel Schaumburg 2 For each generation there is a moment of national tragedy where each person can remember exactly where they were when they heard the terrible news. Tom Brokaw’s “greatest” generation will remember where they were when they heard that Pearl Harbor had been bombed by Japanese warplanes. Younger generations like Gen X’ers will remember their exact location when they learned that the World Trade Center had been hit by two hijacked commercial airliners. For the Baby Boomer generation, that moment is when they heard that President John F Kennedy had been assassinated. When Pearl Harbor was attacked, radio and newspapers broke the news to the public and later newsreels showed the destruction to Americans. However, 9-11 and Kennedy’s assassination were different from Pearl Harbor in that they shared a common trait: the events surrounding the tragedy were televised live to the homes of the American people. Covering the assassination of President Kennedy proved to be a great challenge for television which was still a young medium at the time. The pandemonium surrounding the shocking event was evident in each network’s broadcast; there was no other way to portray the events with reporters who were obviously shaken by the events. The Kennedy assassination coverage tested the television industry to its limits, and helped shape the idea of conspiracy theories inside the minds of the American people. November 22, 1963 At 12:30 (CST) CBS was broadcasting As The World Turns. The main character of the show was deliberating whether or not to remarry his divorced wife.1 Everything seemed to the viewer as an average day. Then at 1:40, CBS anchor Walter Cronkite interrupted programming. The picture on the screen cut to a simple graphic stating: 3 “CBS News Bulletin.” After a brief pause, Cronkite began reading: “Here is a bulletin from CBS News. In Dallas, Texas three shots were fired at President Kennedy’s motorcade in downtown Dallas. The first reports say that President Kennedy has been seriously wounded by this shooting.”2 Cronkite was not on air due to the fact that no cameras were on in the CBS studio, and for cameras to work properly they had to first “warm up” before they could be used for broadcast.3 After Cronkite continued, “More details just arrived. President Kennedy shot today just as his motorcade left downtown Dallas. Mrs. Kennedy jumped up and grabbed Mr. Kennedy, she called ‘Oh no,’ the motorcade sped on. United Press says that the wounds for President Kennedy could be fatal.”4 CBS then switched back to its regular programming, which was currently showing a commercial for NesCafe coffee. The commercial aired for a brief time and then was interrupted again with another bulletin from Cronkite. Meanwhile on NBC and ABC similar bulletins were being filed. Confusion was evident on every network. NBC’s Chet Huntley admitted “Obviously [the information] is going to be sketchy for some time because you can imagine what is happening to every circuit, radio, and telephone between the East Coast and Dallas, Texas at this moment. Obviously the circuits are jammed.”5 Huntley went on to say, “This is no time obviously for speculation. Facts are all that are warranted.”6 However, all of the networks reported unconfirmed accounts on how the assassination took place and the current condition of the slain President. On CBS, Dan Rather reported that Kennedy had died after hearing the report from two Roman Catholic priests who performed last rites on Kennedy. Cronkite relayed this information but also stated that it was completely unconfirmed.7 4 This may have been influenced by the technology available to television news at that time. In 1963, reporters lacked the ability to instantly report on location. Cameras needed time to warm up and information had to be transferred via hard line coaxial cables.8 NBC experienced audio troubles, with each reporter’s voice being echoed quietly a short moment later. NBC correspondent Frank McGee had to relay information from a telephone call by Robert McNeil from Parkland Hospital by repeating McNeil’s words to the audience.9 This was because NBC could not establish a direct audio link from Dallas to the New York studios.10 More audio problems came shortly later, when NBC tried to switch to a live broadcast from its Fort Worth affiliate WBAP. Reporter Charles Murphey had just reported that Dallas police had taken a man into custody when the audio feed cut out. NBC switched back to its New York studios for a short moment and the Dallas audio feed came back online. NBC tried once again to switch to Dallas, but the audio cut out once again. The next time NBC switched back to New York, a loud bang and tone was heard. Anchor Bill Ryan admitted there was a problem with the audio and said that “This is a time of what would probably best be described as controlled panic.”11 Along with technical problems, news anchors faced emotional stress. Each correspondent seemed to attempt to delay the inevitable news that the president was dead.12 Every time a report that the President was dead was given, the anchors of each network reminded the audience that these reports were unconfirmed, as if they were still trying to give the American people hope that their president was still alive. Finally, the confirmation arrived. CBS’s Walter Cronkite stopped relaying a report on the number of Dallas police officers in the area and began reading a new bulletin: “From Dallas, Texas 5 the flash apparently official, President Kennedy died at 1:00 PM Central Standard Time; 2:00 Eastern Standard Time, some thirty-eight minutes ago.”13 Cronkite then stopped, removed his glasses and tried to regain his composure. Obviously choked up, Cronkite continued to report that Vice President Johnson would be taking the oath of office soon. Cronkite paused again after reading the report. NBC’s Frank McGee was still repeating Dallas correspondent Robert McNeil’s reports via telephone when confirmation of Kennedy’s death reached NBC. McGee stated “White House Press Secretary…Malcolm Kilduff…has just announced…that President Kennedy…” McGee paused and grimaced for a brief second, then continued, “died at approximately one o’ clock…”14 Like the rest of America, the networks’ anchors were shocked by the news of Kennedy’s death. In the days that followed November 22, 1963, America began the mourning process and tried to make sense of what had happened. On November 24, Americans watched the most elaborate state funeral in US history live on television. According to Nielsen ratings, 93% of American televisions were tuned to coverage of Kennedy’s funeral.15 However, the audience would be shocked again when Lee Harvey Oswald, the man charged with the murder of President Kennedy, would be shot and killed on live television. Television cameras were focused on the President’s funeral caisson which was preparing to transfer Kennedy’s body from the White House to the Capital Rotunda.16 NBC elected to switch over from coverage of the preparations in Washington, D.C. to the transfer of Oswald in Dallas because NBC’s Frank McGee heard Dallas reporter Tom Petit shout “Give me air! Give me air!” NBC switched just in time to watch Jack Ruby 6 shoot Oswald.17 CBS was also receiving a live feed from Dallas, but opted to stay with the funeral coverage. CBS did switch over to their Dallas feed, but did not see the murder live. However, CBS did replay the video of Oswald being shot on air shortly after.18 Millions viewed the murder of the alleged assassin of the president. ABC’s Howard K. Smith said of Oswald’s murder, “We will never hear this man's story. There is something wrong and we do not know what it is."19 Americans were left with so many unanswered questions, mainly wondering why Oswald did it. This led to the creation of dozens of speculative conspiracy theories surrounding Kennedy’s assassination. However, in the recent years that followed the assassination, many Americans believed what was reported to them in the Warren Report. They believed that Oswald had acted alone and he had acted under his own convictions. However, a few years later Americans began to question the accuracy of the Warren Report and raised questions about a conspiracy surrounding Kennedy’s murder. In 1966 a Gallup poll showed that 6 out of 10 Americans did not believe the Warren Report.20 The media helped fuel some of these doubts. After the assassination of President Kennedy, Americans were in disbelief. They could not believe or accept the fact that the leader of the free world had been murdered by one deranged individual. Kennedy’s death was worth more than that. They felt as if only a mass conspiracy would be a fitting reason for the death of the United States’ president. As soon as Oswald was shot, questions arose. Why would a nightclub manager murder the man who could explain why he killed the president? Was he suddenly overcome with grief, or was it to keep Oswald from revealing more than what 7 we knew? The former explanation could be backed by how the media portrayed Oswald. As soon as Oswald was first shown on camera after being taken into custody by Dallas police, he was described to be a former Soviet sympathizer and a pro-Castro supporter.21 This would suggest that the USSR or Cuba had something to do with the assassination. The media instantly presumed Oswald to be guilty. Newsweek magazine commented on Oswald’s denial that he killed anyone stating “This was a lie.”22 The media may have also led to Oswald’s death by reporting the details of his transfer to Dallas County Jail. The equipment needed to cover the live transfer of Oswald may have created less protection for him, as Jack Ruby was able to hide inside the media circus that followed Oswald.23 Even CBS reported from Dallas that Oswald’s assailant was, “A man wearing a black hat, a brown coat. A man everyone down here thought was a Secret Service agent.”24 With so many people in the basement of the Dallas jail, it was impossible to tell who was who and Ruby was able to remain concealed in the crowd. Also, some of the information reported while covering the assassination of President Kennedy may have led to the creation of conspiracy theories. CBS’s Dan Rather reported that the fatal wound to Kennedy “entered at base of the throat and came out at the base of the neck on the back side.”25 Rather also reported later that after viewing the Zapruder film (the amateur film portraying the president being struck by two shots) he had seen the president’s head “[fall] forward with considerable violence.” This statement fueled the fire of the theories that claim more than one gunman was present and that the president had been struck from the front, causing Kennedy’s head to jerk backward.26 8 The medical reports from Parkland Hospital were supposed to clear up confusion about where the shots were fired from. The task of determining the entrance and exit wound would resolve if Kennedy were struck from behind or the front. However, the medical briefings did just the opposite. When reporters asked surgeon Malcolm Perry if it were possible that one of the shots fired could have struck Kennedy from the front, Perry answered affirmatively. Reporters quickly relayed this answer across the country and by the next morning many Americans were convinced that Kennedy had been struck by a shot fired from the top of the underpass ahead of the motorcade.27 In 1967, CBS sensed that the country did not believe the Warren Commission’s findings and set out to debunk the report with the network’s own findings. CBS spent over a half a million dollars on the documentary investigation.28 The inquiry determined that the Warren Commission’s Report was in fact correct in determining Oswald was the shooter based upon the evidence given. The inquiry and the Warren Report did not, however, rule out the idea that Oswald worked alone or that he was part of a larger conspiracy.29 The American public still had its doubts about the assassination. The biggest piece of evidence in the investigation of the assassination of President Kennedy was the Zapruder film. Dan Rather attempted to gain the rights to it, but was denied and eventually the film was owned by Life magazine.30 The film was not shown on national television until March of 1975. While the film was available in 1963, it was not shown because Americans were not ready to see the gore portrayed in the film and it would have been disrespectful to the Kennedy family. When the entire film was shown on television in 1975, it displayed the graphic footage of Kennedy being struck in the head with a bullet. This film convinced many that the Warren Commission had erred.31 9 In 1976, a second federal investigation began reanalyzing the claims the Warren Commission had made in its report. This House Select Committee on Assassinations was prompted by new acoustic testimony, which suggested that there had been another shooter besides Oswald. After two years, the Committee ruled that there had probably been a second gunman and that Kennedy had probably been “assassinated as the result of a conspiracy.”32 The committee was formed in an effort to regain the American people’s faith in their government. Vietnam, Watergate, and the scandals of the 1970s had destroyed the public’s trust in government, and the House Select Committee on Assassinations sought to regain that trust by pandering to the beliefs of the public.33 The media coverage of the JFK assassination continues even today. Often each November, TV documentaries on the subject surface, reexamining the events of November 22, 1963. These programs tend to focus on the mystery that surrounds the assassination. NBC’s JFK: That Day in November made this statement about the murder of JFK: “Twenty-five years after that murderous day in Dallas, we still don’t know for sure whether Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone.”34 KXAS anchor Alyce Carone stated “Every year we tell this story and every year there seems to be a new twist. A new witness who might seemingly change history. That’s part of the continuing drama surrounding the Kennedy assassination.”35 The media’s continuing coverage of one of America’s darkest times has influenced what people believe about the assassination of President Kennedy. A 1998 CBS poll found that 76% of Americans believed that Oswald did not work alone. 74% believed that there was a government cover-up, and 77% believed that we would never really know the truth.36 10 Anyone who knows about the Kennedy assassination has their own beliefs on what actually happened. These beliefs have been influenced by what people read in history books, what they’ve seen in television documentaries, or what they’ve watched from Hollywood such as Oliver Stone’s JFK. The story of Kennedy’s assassination will remain as the media remembers it, and thus it will remain in the minds of the public who view the media’s interpretation of history.37 The media will continue to shape history through their coverage and consequently their recollection of their coverage. While many media outlets claim they only report the ideas and theories surrounding the assassination, they are unknowingly building support for those claims of conspiracy. Americans still cannot accept that such a president as John F Kennedy could be taken away by a deranged sociopath. Therefore, that is why so many Americans believe that Oswald was part of something much larger—something more fitting for Kennedy’s stature as a man and a leader. We may never know the truth with absolute certainty behind the Kennedy assassination, we can only recall how history and the media remember the events in late November of 1963. 11 Endnotes “America’s Long Vigil.” TV Guide, Jan. 24, 1965 “Four Days In November.” Columbia Broadcasting System, Nov. 17, 1988. Video at Museum of Broadcast Communications Archive online http://archives.museum.tv/archives 3 Thomas Doherty, “Assassination and Funeral of President John F Kennedy,” The Museum of Broadcast Communications 4 “Four Days In November.” Columbia Broadcasting System, Nov. 17, 1988. Video at Museum of Broadcast Communications Archive online http://archives.museum.tv/archives 5 Original News Footage. NBC. Nov 22, 1963. Video at Museum of Broadcast Communications Archive online http://archives.museum.tv/archives 6 Ibid. 7 “Four Days In November.” Columbia Broadcasting System, Nov. 17, 1988. Video at Museum of Broadcast Communications Archive online http://archives.museum.tv/archives 8 Nicholas Tresilian, “The Day Kennedy Died…And After,” Time Society, 1995. 9 Original News Footage. NBC. Nov 22, 1963. Video at Museum of Broadcast Communications Archive online http://archives.museum.tv/archives 10 Thomas Doherty, “Assassination and Funeral of President John F Kennedy,” The Museum of Broadcast Communications 11 Original News Footage. NBC. Nov 22, 1963. Video at Museum of Broadcast Communications Archive online http://archives.museum.tv/archives 12 “America’s Long Vigil.” TV Guide, Jan. 24, 1965. 13 “Four Days In November.” Columbia Broadcasting System, Nov. 17, 1988. Video at Museum of Broadcast Communications Archive online http://archives.museum.tv/archives 14 Original News Footage. NBC. Nov 22, 1963. Video at Museum of Broadcast Communications Archive online http://archives.museum.tv/archives 15 Barbie Zelizer, Covering The Body, 1992 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 62. 16 Thomas Doherty, “Assassination and Funeral of President John F Kennedy,” The Museum of Broadcast Communications 17 “America’s Long Vigil.” TV Guide, Jan. 24, 1965. 18 Ibid. 19 Ibid. 20 “Cronkite Remembers.” Discovery Channel. Sept. 12, 1997. Video at Museum of Broadcast Communications Archive online http://archives.museum.tv/archives 21 “Four Days In November.” Columbia Broadcasting System, Nov. 17, 1988. Video at Museum of Broadcast Communications Archive online http://archives.museum.tv/archives 22 Barbie Zelizer, Covering The Body, 1992 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 72-73. 23 Ibid, 97. 24 “Four Days In November.” Columbia Broadcasting System, Nov. 17, 1988. Video at Museum of Broadcast Communications Archive online http://archives.museum.tv/archives 25 Ibid. 26 Barbie Zelizer, Covering The Body, 1992 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 109 27 Ibid, 56. 28 “Cronkite Remembers.” Discovery Channel. Sept. 12, 1997. Video at Museum of Broadcast 29 Ibid. 30 Thomas Doherty, “Assassination and Funeral of President John F Kennedy,” The Museum of Broadcast Communications 31 Barbie Zelizer, Covering The Body, 1992 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 115. 32 Ibid, 118. 33 Ibid, 112, 117 - 118 34 Leah R. Vandeberg, “Living Room Pilgrimages,” Communication Monographs, March 1995. 35 Ibid. 36 http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/1998/11/20/opinion/main23166.shtml. “CBS Poll: JFK Conspiracy Lives,” Accessed on Internet 11/9/09. 1 2 12 37 Barbie Zelizer, Covering The Body, 1992 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 214.