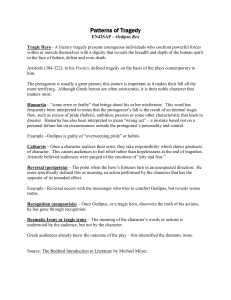

Oedipus Rex - Plot Outline

advertisement

Oedipus Rex - Plot Outline Thebes founded by Cadmus before the play starts – from the teeth of a dragon Thebes was plagued by the Sphinx but Oedipus defeated it and became ruler of the city Thebes is plagued again King Laius told that he would be killed by his son – so bound his ankles and left him on a moor The baby (called Oedipus (sore feet)) was handed from a servant to a shepherd to Polybus, king of Corinth Eventually Oedipus receives a prophesy that he will kills has father and marry his mother – leaves Corinth Whilst traveling he meets his father and kills him The sole survivor (the servant who gave Oedipus away) returns to Thebes and blames a group of robbers Creon is sent to Pythos to speak to Apollo to ask how to rid Thebes of its suffering Apollo: ‘drive pollution, bred of this land, out of the country’ – referring to Oedipus – they have to revenge the death of King Laius by a killing or exiling the murderer King’s murderer was never discovered because Thebes was so troubled by the Sphinx Oedipus threatens the killer: ‘without happiness … may he pine and die,’ and ‘Gods to prevent harvest from the ground nor children from the womb’ Oedipus summons Tiresias to find the killer of Laius – but Tiresias does not want to tell the truth Oedipus accuses Tiresias of the murder – why else would this seer not tell the truth Tiresias gets angry and tells Oedipus he is to blame Oedipus thinks Tiresias & Creon are in a plot to over throw him – Oedipus argues with Creon – Creon says why be king when I have all the benefits now and no responsibility Jocaste tries to placate Oedipus by proving that prophesies don’t come true – she reveals the prophesy to Laius, that he would be killed by son – so son abandoned on moor, so although Laius is dead it could not have been by his son’s hand Jocaste gives details of Laius’ death – at three way cross roads by Phocis – Oedipus realises Oedipus reveals his only past – being told by a drunkard that he was a ‘changeling’ and his leaving in anger to receive his own prophesy – that he would kill his father and marry his mother – hence he left Corinth. He doesn’t realise that Laius was his father and still thinks it was Polybus – cannot leave Thebes for fear of meeting father – is hopeful however that he didn’t kill Laius because the story told by the one survivor is that he was killed by a group of ‘robbers’ and not just one man. This sole survivor (a shepherd) is sent for. Messenger (also the shepherd) arrives from Corinth – Polybus is dead – therefore Oedipus did not kill father Oedipus explains why he left to the Messenger who tells Oedipus that Polybus wasn’t his real father. The Messenger explains he was given the baby by a shepherd (also the sole survivor of the attack) Jocaste realises the truth and tells Oedipus to stop asking questions before it’s too late The shepherd, now an old man, comes and realises what’s happened but won’t tell the truth Oedipus tortures him until he reveals the truth Jocaste runs off stage and hangs herself Oedipus runs off stage, finds her dead and blinds himself Oedipus is exiled by his own curse, Creon is now king The Tragic Hero Aristotle distinguishes between tragedy which depicts people of high or noble character, and comedy which imitates those of low or base character. However noble does not necessarily imply rank or wealth but instead moral rectitude: a noble person is one who chooses to act nobly. Tragic characters are those who take life seriously and seek worthwhile goals, while comic characters are "good-for-nothings" who waste their lives in trivial pursuits. The hero of tragedy is not perfect, however. To witness a completely virtuous person fall from fortune to disaster would provoke moral outrage at such an injustice. Likewise, the downfall of a villainous person is seen as appropriate punishment and does not arouse pity or fear. The best type of tragic hero, according to Aristotle, exists "between these extremes . . . a person who is neither perfect in virtue and justice, nor one who falls into misfortune through vice and depravity, but rather, one who succumbs through some miscalculation". The term hamartia, which Golden translates as "miscalculation," literally means "missing the mark," taken from the practice of archery. Much confusion exists over this crucial term. Critics of previous centuries once understood hamartia to mean that the hero must have a "tragic flaw," a moral weakness in character which inevitably leads to disaster. This interpretation comes from a long tradition of dramatic criticism which seeks to place blame for disaster on someone or something: "Bad things don't just happen to good people, so it must be someone's fault." This was the "comforting" response Job's friends in the Old Testament story gave him to explain his suffering: "God is punishing you for your wrongdoing." For centuries tragedies were held up as moral illustrations of the consequences of sin. Given the nature of most tragedies, however, we should not define hamartia as tragic flaw. While the concept of a moral character flaw may apply to certain tragic figures, it seems inappropriate for many others and searching for the tragic flaw in a character often oversimplifies the complex issues of tragedy. For example, the critic predisposed to looking for the flaw in Oedipus' character usually points to his stubborn pride, and concludes that this trait leads directly to his downfall. However, several crucial events in the plot are not motivated by pride at all: (1) Oedipus leaves Corinth to protect the two people he believes to be his parents; (2) his choice of Thebes as a destination is merely coincidental and/or fated, but certainly not his fault; (3) his defeat of the Sphinx demonstrates wisdom rather than blind stubbornness. True, he kills Laius on the road, refusing to give way on a narrow pass, but the fact that this happens to be his father cannot be attributed to a flaw in his character. (A modern reader might criticize him for killing anyone, but the play never indicts Oedipus simply for murder.) Furthermore, these actions occur prior to the action of the play itself. The central plot concerns Oedipus' desire as a responsible ruler to rid his city of the gods' curse and his unyielding search for the truth, actions which deserve our admiration rather than contempt as a moral flaw. Oedipus falls because of a complex set of factors, not from any single character trait. This misunderstanding can be corrected if we realize that Aristotle uses hamartia not as character trait but rather as an incident in the plot: caught in a crisis situation, the protagonist makes an error in judgment or action, "missing the mark," and disaster results. Most of Aristotle's examples show that he thought of hamartia primarily as a failure to recognize someone, often a blood relative. For Aristotle the most tragic situation possible was the unwitting murder of one family member by another. Mistaken identity allows Oedipus to kill his father Laius on the road to Thebes and subsequently to marry Jocasta, his mother; only later does he recognize his tragic error. However, because he commits the crime in ignorance and pays for it with remorse, self-mutilation, and exile, the plot reaches resolution or catharsis, and we pity him as a victim of ironic fate instead of accusing him of blood guilt. While Aristotle's concept of tragic error fits the model example of Oedipus quite well, there are several tragedies in which the protagonists suffer due to circumstances totally beyond their control. In the Oresteia trilogy, Orestes must avenge his father's death by killing his mother. Aeschylus does not present Orestes as a man whose nature destines him to commit matricide, but as an unfortunate, innocent son thrown into a terrible dilemma not of his making. In The Trojan Women by Euripides, the title characters are helpless victims of the conquering Greeks; ironically, Helen, the only one who deserves blame for the war, escapes punishment by seducing her former husband Menelaus. Heracles, in Euripides' version of the story, goes insane and slaughters his wife and children, not for anything he has done but because Hera, queen of the gods, wishes to punish him for being the illegitimate son of Zeus and a mortal woman. Hamartia plays no part in these tragedies. It is true that the hero frequently takes a step which initiates the events of the tragedy and, owing to his own ignorance or poor judgment, acts in such a way as to bring about his own downfall but this cannot make him guilty in the same way that we all believe we cannot really be guilty for the accidental wrongs we do. Thus, the hero’s fate, despite its immediate cause in his actions, comes about because of wider, more universal issues: the limited nature of mankind, our inevitable ignorance in an unfathomably complex world, and the role played by chance, destiny or the gods in human affairs. Given these examples, we should remember that Aristotle's theory of tragedy, while an important place to begin, should not be used to prescribe one definitive form which applies to all tragedies past and present. Aristotle’s Principles of Tragedy The word "tragedy" refers primarily to a tragic drama in which a central character called a tragic protagonist or hero suffers some serious misfortune which is not accidental and therefore meaningless, but is significant in that the misfortune is logically connected with the hero's actions. Tragedy stresses the vulnerability of human beings whose suffering is brought on by a combination of human and divine actions, but is generally undeserved with regard to its harshness. This genre, however, is not totally pessimistic in its outlook. Although many tragedies end in misery for the characters, there are also tragedies in which a satisfactory solution of the tragic situation is attained In his work On the Art of Poetry Aristotle, a Greek Philosopher of the 4th Century BC, attempted to define tragedy as: ‘a representation of an action that is worth serious attention, complete in itself, and of some magnitude; in language enriched by a variety of artistic devices appropriate to the several parts of the play; presented in the form of action, not narration; by means of pity and fear bringing about the catharsis of such emotions.’ Aristotle distinguishes between tragedy which depicts people of high or noble character, and comedy which imitates those of low or base character. However, nobility in this case does not refer to wealth or status but, instead, moral rectitude. As such, even a poor man can be a tragic hero as long as he is morally good. The First Principle: Plot According to Aristotle, the plot of a tragedy should be determined by a logical chain of cause-and-effect events where one action leads logically to an outcome and thence to a further action and so on without the arbitrary interruptions of chance, gods or the whims of a character: personal motivations should thus form an intricately connected part of the cause and effect chain of actions. This unstoppable ‘unravelling’ or ‘lusis’ of events creates a sense of inevitability about the final tragic outcome. ‘Unity of Action’ is therefore created as all of the events witnessed by the audience are integral to the central storyline and, undistracted by sub-plots and irrelevancies, we are forced to focus on the tragedy unfolding around the protagonist on stage. The more universal the nature of this tragedy, i.e. the more easily it can be applied to ourselves or others, the more effective it is. Rather than simply consisting of a ‘change of fortune’ or ‘catastrophe’ where the protagonist falls from greatness to ignominy an ideal plot will be complex in that the protagonist should attempt to avert disaster but have these attempts thwarted as his actions actually bring him closer to doom (an effect called ‘peripeteia’ – the reversal of intention). An additional moment of ‘anagnorsis’ or ‘realisation’ can increase the tragic impact of the drama as the protagonist realises it is indeed his very attempts to avert disaster that have actually been instrumental in bringing about catastrophe. As such, if Oedipus’ fatal flaw is his ignorance, then the peripeteia are really the accidentally self-destructive actions he takes in blindness and the anagnorsis is his realisation of the truth and the gaining of the knowledge that he previously lacked. The Second Principle: Character Tragic characters should be true to life yet more idealized, more noble. The protagonist should be renowned and prosperous, so his change of fortune can be from good to bad. This change “should come about as the result, not of vice, but of some great error or frailty in a character.” Such a plot is most likely to generate pity and fear in the audience, for “pity is aroused by unmerited misfortune, fear by the misfortune of a man like ourselves.” Catharsis Endless debates have centered on the term "catharsis" which Aristotle unfortunately does not define. Some critics interpret catharsis as the purging or cleansing of pity and fear from the spectators as they observe the action on stage; in this way tragedy relieves them of harmful emotions, leaving them better people for their experience. However others prefer to think of catharsis not as the effect of tragedy on the spectator but as the resolution of dramatic tension within the plot. The dramatist depicts incidents which arouse pity and fear for the protagonist, then during the course of the action, he resolves the major conflicts, bringing the plot to a logical and foreseeable conclusion. This second explanation of catharsis helps to explain how an audience experiences satisfaction even from an unhappy ending. Human nature may cause us to hope that things work out for Antigone, but, because of the insurmountable obstacles in the situation and the ironies of fate, we come to expect the worst and would feel cheated if Haemon arrived at the last minute to rescue her, providing a happy but contrived conclusion. In tragedy things may not turn out as we wish, but we recognize the probable or necessary relation between the hero's actions and the results of those actions, and appreciate the playwright's honest depiction of life's harsher realities. Oedipus Rex - Quotations Characters Oedipus “Hard-hearted I must be, did I not pity such petitioners” “Whoe’re he be, I order that of this land… none entertain him, none accost him… but all men from their houses banish him” “Worst of traitors! Know, I suspect you joined to hatch the deed” “I acknowledge, much. Still, her who lived I fear” “You will not speak of grace - you shall perforce!” “Give me no counsel now… I have sinned sins” Creon “Do me this favor; hear me say as much as you have said; and then, yourself decide.” “In matters where I have no cognizance I hold my tongue.” “Not as a mocker come I, Oedipus.” “Yes, it is I vouchsafed this boon, aware what joy you have and long have had of them.” Jocasta “Listen and learn, nothing in human life turns on the soothsayers’ art.” “Now let us go within. I would do nothing that displeases you.” “Why should men be fearful, O’er whom Fortune is mistress, and foreknowledge of nothing sure?” “Best take life easily, as a man may.” Tiresius “Alas! How terrible it is to know, where no good comes of knowing! “I will not bring remorse upon myself and upon you.” “I am your equal, there; for I am Loxias’ servant, and not yours” “I say – you have your sight, and do not see what evils are about you… Yea, you are ignorant” Themes Inescapable Fate/Inevitability “The man is dead; and now, we are clearly bidden to bring to account certain his murderers” “Me miserable! It seems I have but now proffered myself to a tremendous curse not knowing!” “Nay, it cannot be that having such a clue I should refuse to solve the mystery of my parentage!” “But I must hear - no less” “Think not to have all at thy pleasure; for what thou didst attain to far outwent thy measure” Oedipus’ Rashness/Ignorance “I shall dispel this plague-spot; for the man, whoever it may be, who murdered him” “He should become an inmate of my dwelling, that I may suffer all that I invoked on these just now.” “Quick, someone, twist his hands behind him!” “he went raging all about, beseeching us to furnish him a sword” “he raised his hand and stabbed his eyes” Sight and Blindness/darkness “And if you were not blind, I should aver the act was your work only!” “You have your sight, and do not see what evils are about you…” “Blind as you are in eyes, and ears, and mind!” “Who has no eyes to see with, but for gain, and was born blind in the art!” “I have no eyes for what my masters do.” “he lifted them, and smote the nerves of his own eyeballs - that they should see no more evils” “Why was I to see, when to descry no sight on earth could have a charm for me? “I would have tried to seal up all this miserable frame and live blind, deaf to all things” The History of Greek Tragedy The Dionysia: Tragic Festival Each spring Athens (when it was an independent city state under the kingship of Pericles) held a festival in celebration of the god Dionysus at which the contest for best tragedy was a central part. Tragic playwrights submitted three serious dramas and a comedy called a satyr play, often on a similar theme. This was not a business enterprise but rather a central part of the religious worship of the city and so it was controlled by the State: the playwrights were chosen by judges and were allocated their actors by lot to ensure fairness. The tragic poets competed with one another and, during the 5th Century BC (the ‘Golden Age’ of Greek drama) Aeschylus won thirteen first place victories, Sophocles, twenty four, and Euripides, five. The Theatre The theater of Dionysus was, like all ancient Greek theaters, an open-air auditorium and, due to the lack of adequate artificial lighting, performances took place during the day. Scenes set at night had to be identified as such by the actors or the chorus; the audience, upon receiving these verbal cues, had to use its imagination. In general, the action of tragedy was well served by presentation in an open-air theater since interior scenes, which are common in our typically indoor theaters, are all but non-existent in tragedy. The action of a tragedy normally takes place in front of palaces, temples and other outdoor settings. This seemed natural to the ancient audience because Greek public affairs, whether civic or religious, were conducted out of doors as was much of Greek private life due to the relatively mild climate of the Aegean area. Costume and setting would have been minimal. There was a central dancing area for the Chorus (called an orchestra) and, in place of a stage, there would have been a tent (called a skene – the ancestor of our modern word scene) in which the actors could change. The side of the skene facing the audience may have had a relevant picture of a palace or temple painted on it but that would have been the extent of setting. An ‘ekkyklema’ (literally ‘wheeled out thing’) would occasionally have been hidden inside the skene.‘ This device was used to display the results of some grisly off-stage action to the audience and would have been appropriately adorned with blood and bodies and ‘wheeled out’ when required. A ‘mechane’ which could be used to hoist characters playing gods on to the roof of the skene would also occasionally be used: this is the source of the term ‘deus ex machina’. The Actors By the middle of the fifth century three actors were required for the performance of a tragedy. In descending order of importance of the roles they assumed they were called the protagonist 'first actor', (a term applied in modern literary criticism to the central character of a play not the actor), deuteragonist 'second actor' and tritagonist 'third actor'. Aeschylus was the first playwright to have presented more than one character on stage at a time and is thus credited with the invention of dramatic dialogue. Since most plays required more than three characters most actors played more than one role and masks were used to indicate character changes as well as to enable male actors to more convincingly play female characters as women were not allowed to perform on stage in Ancient Greece. The Chorus The chorus often portrayed the people of the city, responding to the protagonist as an ideal audience. During the choral odes their singing and dancing provided variety and spectacle, allowing time for the actors to change into other costumes for the next scene. The importance of singing throughout the performance suggests that the modern parallel for tragedy is actually opera rather than ‘straight’ drama. The first function of a tragic chorus was to chant an entrance song called a parados as they marched into the orchestra. Once the chorus had taken its position in the orchestra, its duties were twofold: firstly, it engaged in dialogue with characters during the episodes and secondly it sang or danced during the stasima (singular = stasimon). Private reading of tragedy deprives us of the visual and aural effects created by the Chorus and actors which were important elements of this genre: we miss the scenery, inflection of actors' voices, gestures and postures, costumes and masks, singing, dancing, the sounds of the original language and its various poetic rhythms. This does not render our reading of tragedy worthless because words are still the most important means of communication, however imagination must be used as much as possible in order to compensate for those theatrical elements lost in reading tragedy.