Progressivism and Propaganda: Managing American Public Opinion

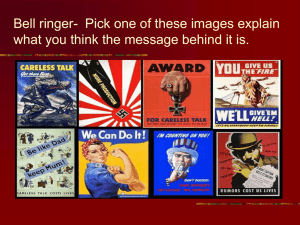

advertisement

Auerbach--1 Progressivism and Propaganda: Managing American Public Opinion, 1896-1934 As the title indicates, my project brings together two familiar but slippery concepts, with the aim of casting new light on progressivism as it developed at the start of the twentieth century, as well as on propaganda as a distinct mode of mass persuasion. Rather than approach progressivism as an array of policies, a cluster of aspirations, a political agenda, or a fixed ideology (more or less coherent), I propose to examine the reformist impulses defining this era as fundamentally a set of tensions or debates about the nature of American public opinion itself. The desire to revitalize and sustain a modern robust democracy, I propose to show, demanded in both theory and practice a new understanding of what constituted the public, and how this general will could be harnessed for the good of the nation. As Woodrow Wilson remarked during his 1912 presidential campaign, “the business of government is to organize the common interest against the special interests.” Managing the common interest required that citizens be convinced of certain facts for specific purposes, not just presented with information. Under an emergent middle-class professional ethos that expanded rapidly during the 1890s, government officials, elected politicians, the press, educators, and corporations all had a stake in trying to deliberately direct this public, no longer taken for granted as a transcendental unity (“The People”), as in traditional nineteenth-century formulations, but rather treated as a multitude of competing, often chaotic points of view. If such a thing as the public still existed, the progressives reasoned, it had become increasingly disorganized, in need of benevolent administrative intervention. One hundred years later, with the expansion of the state and the growth of newer channels of communication (radio, television, the Internet), the fate and future of an American public, or publics, has become an even more pressing concern—who, where, how it might be mobilized – so that carefully analyzing progressivism’s grappling with the problem a century prior carries great import for understanding and contextualizing current debates about the status of the public and the public sphere in fostering participatory democracy. Focusing on the question of how public opinion is shaped and organized leads me to reconsider propaganda, a word that has fallen out of favor among political and social scientists over the past few decades. My ongoing interest in the term stems from my work co-editing The Oxford Handbook of Propaganda Studies, a forthcoming large interdisciplinary collection of original essays that examines practices of mass persuasion from 1622 (the word’s inception in a papal bull designed to propagate the true Catholic faith) to the Middle East uprisings in the spring of 2011. By looking at a wide variety of nations, institutions, media, and theories, we hope to break free of the habit of viewing the concept pejoratively through the lens of the twentieth century, especially in the aftermath of two world wars and the rise of totalitarianism. In this perspective, “propaganda” is simply what the enemy does. But prior to global conflict, the word was used more impartially to describe the crystallizing of public opinion, such as when the president of the University of Wisconsin in 1910 lauded Theodore Roosevelt’s creation of the National Conservation Association as the “center of a great propaganda for conservation.” Restoring this neutral or even positive usage in relation to progressivism will allow us to see how publicity techniques both before and after World War I continued inevitably to exert a powerful influence on American life through a variety of venues, from mass media and politics to corporate public relations. Auerbach--2 The argument of my book develops chronologically over five chapters. The first chapter, titled “Giving Direction to Opinion” (a phrase taken from Woodrow Wilson’s 1908 study Constitutional Government) begins by examining various intellectual, political, and commercial contexts near the end of the nineteenth century that sometimes in concert, sometimes in opposition, began to erode confidence in the normative ideal of a unitary American public: the influence of European social scientists who emphasized how modern mass society was governed by powerful irrational forces beyond the control of individuals; the rise of pragmatism, a homegrown brand of anti-formalism and antiidealism insisting that facts could not be divorced from values and uses; the establishment of the first “Publicity Bureau” in 1900, advising corporate clients such as the railroads and AT&T how best to promote and protect their interests; a new mode of “Front Porch” presidential campaigning that helped to propel William McKinley in 1896 into office with the carefully orchestrated dissemination of heavily controlled news and image bites. But less than a decade later, I go on to show in this chapter, another sort of press, national magazine feature writers rather than newspaper reporters, would begin to take on a far more active role. Closely dissecting the manufacture of public opinion by big business through the misleading practices of publicity bureaus and other covert means, these muckrakers, as Roosevelt disparagingly called them in 1906, sought to expose and combat one of sort of publicity with a counter publicity of their own. My second chapter, titled “The Conscription of Thought,” after an essay by John Dewey, discusses how these very same reform-minded journalists, most notably George Creel, took over the task of directing the state’s own massive propaganda apparatus during WWI: the Committee for Public Information (CPI) set up by President Wilson in April 1917 a week after the US entered the conflict. These intimate ties between muckraking and propaganda-making demonstrate how certain methods of mass persuasion could be detached from their original purposes and deployed to other instrumental ends. But there is a deeper connection between progressive muckraking and wartime propagandizing. In attempting to recast public opinion against corporations, magazine writers like Ray Stannard Baker, Ida Tarbell, and Lincoln Steffens were seeking to direct some of the regulatory duties of the state. In this regard, TR’s disdain for the muckrakers may have had less to do with their aims, tone, or methods than their perceived threat to his own executive prerogative as the nation’s chief opinion leader and arouser of fierce indignation. By appointing Creel to head the CPI eleven years to the very day after TR coined the term “muckraker,” Wilson for the first time in US history effectively fused press, state, and private business into a single ministry of propaganda to advertise the American gospel of democracy both domestically and abroad. The entire war effort in this sense at once culminated a crucial proselytizing strain of progressivism as well as represented its fatal overreaching. A condition of exceptional crisis was seized and managed in ways that let state power exceed the bounds routinely restraining it. The next three chapters of my book explore the legacies of progressivism and propaganda in the disillusioning wake of the war. The third chapter, “Search for the Public,” will serve as the theoretical centerpiece of my study, focusing on the penetrating analyses of the state and public opinion by Walter Lippmann and John Dewey. It has become a commonplace to stage the intellectual encounter between Lippmann and Dewey during the 1920s as kind of a contest, with Dewey’s more upbeat faith about democratic possibility triumphing over Lippmann’s more pessimistic assessment, which Auerbach--3 concluded that in the absence of “omnicompetent citizens” capable of informed civic engagement, public opinion needed to be mediated and managed by elite experts. Looking past the appeal of Dewey’s egalitarianism, I stress the cogency and consistency of Lippmann’s thinking from Drift and Mastery (1914), which opened with a shrewd evaluation of the allure of muckraking, through Liberty and the News (1920), which argued that the American press was not a solution but part of the very problem plaguing modern democracy, to Public Opinion (1922) and The Phantom Public (1925), which rejected the notion of any common interest altogether in favor of insiders and outsiders, defined not by social class but rather by proximity to power. The fourth chapter, “Invisible Government,” turns to another legacy of the war, the institutionalizing of the “science” of public relations by the two self-proclaimed fathers of the field, Edward Bernays and Ivy Ledbetter Lee. Like Lippmann, Bernays and Lee cut their professional teeth by performing public service during the war, Bernays actually employed by the CPI, and Lee working as a publicist for the Red Cross. A double nephew of Sigmund Freud, Bernays (like Dewey) was powerfully influenced by Lippmann’s work. But instead of trying to contest Lippmann’s troubling arguments, Bernays in his two books from the 1920s, Crystallizing Public Opinion (1923) and Propaganda (1928) blithely embraced manipulating the perceptions, ideas, taste, and habits of the masses to bring order to the chaos of democracy. “Invisible government,” he called this ruling/schooling, a deliberate process of “regimenting the public mind.” Given the ascendancy of big business during the 1920s, it may be something of a stretch to consider Bernays a progressive, but clearly his reasoning about the need for social direction by thoughtful specialists is in keeping with the logic of progressivism. Shifting focus from the state to private corporations, Bernays thus reconfigured the democratic public sphere in two crucial ways: first, he saw public relations counsels as mainly serving particular clients, thereby substituting a system of commercial patronage for the self-sacrificing “New Nationalism” that TR and other progressives had called for before the war; and second, he reconstructed citizens primarily as consumers driven by a complex set of emotions and desires—far more than simple, passive dupes. While the CPI concerned itself with regulating a relatively narrow range of citizens’ patriotic feelings, centered mainly on pride, hatred, and fear, once propaganda was tied to motivating consumption, then the collective unconscious of the American public (to use Freudian terminology) would become fair game. And yet in targeting politically marginalized groups such as women and minorities, these PR experts arguably produced a more capacious if perhaps more fragmentary vision of a public than the mainstream press or politicians of the period. Up to this point in my study, I have confined myself primarily to domestic matters. But my fifth and final chapter, “The Business of the World,” takes a transnational turn. My title is borrowed from a speech President Wilson made soon after the war, when he declared that “the men who do the business of the world now shape the destinies of the world.” For public relations counsels like Bernays and Lee, this meant drawing on their wartime international experience in order to help shape opinion by and about other countries around the globe, nations during the 1920s regarded less as allies or adversaries than as potential lucrative markets for American trade. Bernays, for instance, got the idea to start his public relations agency in 1919 while lobbying for US recognition of Lithuanian independence, and Lee traveled to the USSR in 1927 to gauge the level of Auerbach--4 communist propaganda for and against America and American business. Here the pioneering work of Lee and Bernays anticipates the current worldwide fusion of public diplomacy, financial interests, and private sector opinion making. For Lee this ambition to develop foreign markets would give him problems, as he was investigated shortly before his death in 1934 by a congressional committee (whose findings are in the National Archives) for advising the German chemical firm IG Farben, then under Nazi direction. In a rather curious but no less ominous way, the Nazis would also indirectly intersect with Bernays, who casually mentions in his autobiography that an American foreign correspondent told him of a conversation in 1934 he had with Joseph Goebbels, who proudly pointed to a Bernays book in his library as a source of inspiration for the recently appointed Minister of Propaganda. These portentous encounters with Nazi Germany mark the end of this study. So what is revealed by the historical trajectory of my project, from progressive muckrakers at the beginning of the century to equally influential public relations counsels abroad during the start of the FDR administration? I see three broad patterns with significant consequences for understanding the shaping of American public opinion today. First, given the gradual loss of faith in the possibility of a coherent public, we note key shifts in who primarily controlled opinion, from the intense rivalry among government, business, and media before WWI, to the supremacy of the state during the war (confirming Randolph Bourne’s remark that “war is the health of the state”), to corporate dominance during the 1920s, with a strange transnational twist reverting back to state control in 1934 when techniques of American public relations were carried over, to an extent that requires further research, into the National German Socialist Workers Party. Second, during the heyday of progressivism before the war, we can detect another side to the frictions among competing interests—the emergence of a revolving door between public and private sectors, with the press often serving as the relay between the two. The first Publicity Bureau, for example, was founded in 1900 by ex-journalists who also hired ex-government officials (statisticians), and whose first client was Harvard University, to be quickly followed by large transportation industries and communications companies, who wanted to push back against the threat of being heavily regulated as pubic utilities for the common good. Third, tracing the intersections between progressivism and propaganda, we can discern a pair of seemingly countervailing tendencies, as Lippmann was the first to clearly see—the profusion of mass media to the point of complete, but bewildering saturation, and the splintering of a common will into what scholars recently have analyzed as a multitude of publics (plural) and counter publics (plural). To understand how American democracy can thrive or perhaps just survive in such a contemporary environment, we would do well to closely examine the making and managing of public opinion during the first three decades of the last century. I have currently drafted the first chapter of the book, and plan this coming year to conduct research on the CPI at the National Archives, with the aim of completing the final three chapters during my fellowship leave. Having published books on nineteenth and twentieth century American literature and film, I am eager to examine key aspects of US politics, mass media, and public opinion in order to expand my expertise and standing in the field of American studies more broadly. Auerbach--5