The Comparative Commentary

advertisement

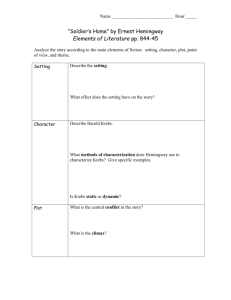

The Comparative Commentary What’s in a question? Task & Question Analysis Always begin by determining what you are expected to do. Break the task or question down to its key terms and components. I. Step One: Preparation 1. Discuss the similarities and differences between the texts and their theme(s). Include comments on the ways the authors use elements such as structure, tone, images and other stylistic devices to communicate their purposes. 2. Sample Task Analysis: (1) Theme(s): identify the key theme(s) in the texts and analytically discuss them. Create an argument that used the theme(s) and it will provide the framework for the entire essay. (2) Author(s): refer to them using their last names, if known, but more importantly, work into the discussion the kind of authors they are – poet, novelist, playwright, screenwriter, journalist, etc. Awareness of genre is important. (3) Authors purpose…: discuss the purpose of the author and how they accomplishing the intended effect. (4) Structure, Tone, Imagery, Other Stylistic Devices: deal substantively with each of the big three, and where relevant, I would bring in discussion of “other devices.” In most cases you will want to relate how these elements work in relation with the theme(s) you have identified and framed the essay with. (5) Purposes: Implicit in this word is the mandate for you to identify the audience for this text and the “to what effect” aspect of a good argument. It is simply not enough to play “I spy” (“See, here is where Shakespeare uses an image of the theater, and over here…”) – you must look at how the author uses a particular device and for what purpose (“When Shakespeare uses the word ‘mask,’ he echoes not only the theme of appearance versus reality, but sets up a theatrical motif that…”). II. Embracing the Intellectual Work A. Before you start writing, sketch out a chart or note sheets and thoroughly dissect the texts. Comparing idea with idea, theme with theme, tone with tone, point of view, purpose, imagery, etc…Devote 15 – 20 minutes to this task. III. Step Two: Writing the Essay: The goal here is different from that of most other essays. Here the goal is to briefly frame the key points and point of view that you are going to take in your analysis. Set up a clear argument and move right into the comparative analysis. A. What should my Paper look like when I am finished? Your essay should be between six and eight paragraphs, allowing you to write an introduction and conclusion along with a body paragraphs for each of the following: theme(s), structure, tone, images, and purpose/audience.1 Again, it is best if you can use “theme” as the thread that ties the entire essay together, rather than treating separately. 1 B. Writing the introduction. This should be short and to the point. The strongest essays will employ a hook, and provide a clear “read” of the overall texts. All essays must provide an argument that lays out your position (what the authors are doing, how, and to what effect) and presents a map to the way you will approach your comparative commentary. 1. Example: Confronting the inevitability of death is an age-old human concern. Donne’s 17th century sonnet boldly challenges a personified Death, strengthened by Christian faith, which promises eternal life. Hemingway’s 20th century character Nick, on the other hand, mirrors classic existential sorrow as he ponders his readiness to enter the deeper and darker waters of death, followed by nothingness. Both authors effectively use distinct structures, tones, images, and other devices unique to the genres in which they work to represent the theme of how humans might confront death. C. Moving your argument forward: Transitions, Body Paragraphs, and Making Analytical Points. 1. Transitions & Organizational Logic: As the reader moves from your introduction into the body of your commentary, she should feel as if she is crossing a bridge. For instance, based upon what you have written in your introduction, your reader should be able to anticipate you will discuss Donne first, since he is the first author you introduce, and that the first point you will examine will deal with structure, because it was the first you introduced. The sequencing should hold to an organizational logic. 2. Arguments are Made: Decide what the one or two most important aspects you want to make your reader to see and understand. Find at least one example of each aspect. Follow the example with discussion of what is important to see and understand, as well as link back to your argument. 3. Example 1: The fourteen-line sonnet structure has been used by poets since the 13th century, though with many variations in meter and rhyme scheme. Hirsch argues that the form forces a logical compression that is ideal for exploring complex issues like love and death in a rhetorically compelling way. Donne’s poem illustrates this. He opens and closes with two declarations “Death be not proud” and “death, thou shalt die.” This is what essayists often do. They make an assertion in the introduction and illustrate the validity of this declaration in the body, and then revisit their point in a compellingly new way in the conclusion. To tell a personified death that he shall “die” is quite a powerful statement. But a personified death is not Donne’s real audience. Donne seeks to persuade his fellow humans that they should not fear dying, for if they have Christian faith they will earn eternal life in heaven. D. Writing Conclusions. This should be short and to your point. That is, you should focus upon your thematic position, and how the cumulative and integrated effect of the range of each author’s art bears this out. 1. Example: It is natural to fear death, and to find ways to confront and resolve this fear. Most people wrestle with this fear, but when artists make this fear visible it assists all who engage with it to think. And generating thought is the effect that both Donne and Hemingway accomplish, though Donne seeks to settle and calm while Hemingway seeks to disturb and agitate. Through their explorations of death and the “beyond,” these authors give us the potential to lead a richer life, for as Socrates says, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” Elements Who? Author Name & Type What? Genre Why? Target Audience and Purpose Theme(s) Structure Tone Images Other Device 1 Other Device 2 Embracing the Intellectual Work: Begin with a Chart Text A Text B Text 1 Death be not proud, though some have called thee Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so; For those whom thou think’st thou dost overthrow Die not, poor death, nor yet canst thou kill me. From rest and sleep, which but thy pictures be, Much pleasure; then from thee much more must flow, And soonest our best men with thee do go, Rest of their bones, and soul’s delivery.2 Thou art slave to fate, chance, kings, and desperate men, And dost with poison, war, and sickness dwell; And poppy or charms can make us sleep as well, And better than thy stroke; why swell’st3 thou then? One short sleep past, we wake eternally, And death shall be no more; death, thou shalt die. 5 10 John Donne (1633) 2 3 Rescue, deliverance; also, the bringing forth or “birth” of the soul. Puff up with pride. Text 2 Nick had one good trout. He did not care about getting many trout. Now the stream was shallow and wide. There were trees along both banks. The trees of the left bank made short shadows on the current in forenoon sun. Nick knew there were trout in each shadow. In the afternoon, after the sun had crossed toward the hills, the trout would be in the cool shadows on the other side of the stream. The very biggest ones would lie up close to the bank. You could always pick them up there on the Black. When the sun was down they all moved out into the current. Just when the sun made the water blinding in the glare before it went down, you were liable to strike a big trout anywhere in the current. It was almost impossible to fish then, the surface of the water was blinding as a mirror in the sun. Of course, you could fish upstream, but in a stream like the Black, or this, you had to wallow against the current and in a deep place, the water piled up on you. It was no fun to fish upstream with this much current. Nick moved along through the shallow stretch watching the banks for deep holes. A beech tree grew close beside the river, so that the branches hung down into the water. The stream went back in under the leaves. There were always trout in a place like that. Nick did not care about fishing that hole. He was sure he would get hooked in the branches. It looked deep though. He dropped the grasshopper so the current took it under water, back in under the overhanging branch. The line pulled hard and Nick struck. The trout threshed heavily, half out of the water in the leaves and branches. The line was caught. Nick pulled hard and the trout was off. He reeled in and holding the hook in his hand, walked down the stream. Ahead, close to the left bank, was a big log. Nick saw it was hollow; pointing up river the current entered it smoothly, only a little ripple spread each side of the log. The water was deepening. The top of the hollow log was gray and dry. It was partly in the shadow. Nick took the cork out of the grasshopper bottle and a hopper clung to it. He picked him off, hooked him and tossed him out. He held the rod far out so that the hopper on the water moved into the current flowing into the log. Nick lowered the rod and the hopper floated in. There was a heavy strike. Nick swung the rod against the pull. from Ernest Hemingway’s short story Big Two-Hearted River 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 Intro Sample Essay Confronting the inevitability of death is an age-old human concern. Donne’s 17th century sonnet boldly challenges a personified Death, bolstered by Christian faith, which promises eternal life. Hemingway’s 20th century character Nick, on the other hand, mirrors classic existential angst as he ponders his readiness to enter the deeper and darker waters of death, followed by nothingness. Both authors effectively use distinct structures, tones, images, and other devices unique to the genres in which they work to represent the theme of how humans might confront death. Structure The fourteen-line sonnet structure has been used by poets since the 13th century, though with many variations in meter and rhyme scheme. Hirsch argues that the form forces a logical compression that is ideal for exploring complex issues like love and death in a rhetorically compelling way. Donne’s poem illustrates this. He opens and closes with two declarations “Death be not proud” and “death, thou shalt die.” This is what essayists often do. They make an assertion in the introduction, illustrate the validity of the assertion in the body, and then revisit their point in a compellingly new way in the conclusion. To tell a personified death that he shall “die” is quite a powerful statement. But a personified death is not Donne’s real audience. Donne seeks to persuade his fellow humans that they should not fear dying, for if they have Christian faith they will earn eternal life in heaven. Structure Though traditionally not as compressed a form as poetry, the short story is known among narrative fiction as distilling experience down to what is essential, often a simple moment. Hemingway is particularly well known for revolutionizing the art form through sparing prose. In this excerpt we see how Hemingway creates seven short, almost stanza-like, paragraphs. Anaphorically, Hemingway begins four of these paragraphs with Nick+verb. The effect of this is to force the reader to focus, intimately, upon every action of the character. The intimacy created is important, for the river Nick wades in to fish is the river of life. So when we reach the first line of paragraph five, where Hemingway simply says, “It looked deep though,” we feel with Nick that walking into the deep dark waters of life’s uncertainty legitimately induces fear, particularly if we believe there is no existence beyond the life we now live. In a post-WWI world many people bitterly embraced a perspective that there is no God. When you die, you die, and that’s it. Here, in this excerpt, structure is used to convey trepidation concerning death and existence. Blah, blah, blah… Tone Donne Tone Hemingway Imagery Donne Blah, blah, blah… Blah, blah, blah… Imagery Hemingway Purpose & Audience Donne Purpose & Audience Hemingway Conclusion Blah, blah, blah… Blah, blah, blah… Blah, blah, blah… It is natural to fear death, and to find ways to confront and resolve this fear. Most people wrestle with this fear, but when artists make this fear visible it assists all who engage with it to think. And generating thought is the effect that both Donne and Hemingway accomplish, though Donne seeks to settle and calm while Hemingway seeks to disturb and agitate. Through their explorations of death and the “beyond,” these authors give us the potential to lead a richer life, for as Socrates says, “The unexamined life is not worth living.”