Conducting the Focus Group

advertisement

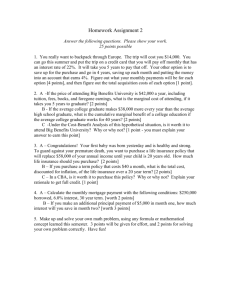

Sally Thomas: "Suffragists Speak Final Project"--draft of final report: Focus Group sthomas@sims.berkeley.edu Focus Group In conjunction with SIMS 214: Needs Assessment and Evaluation of Information Systems, Sally Thomas researched the theory and practice of conducting focus groups. She also was fortunate to attend a focus group workshop sponsored by the California Digital Library, in preparation for a series of focus groups they were planning to conduct. This background was useful in helping us to organize a test focus group. We determined that a focus group could be particularly useful in the needs assessment process, to generate a dynamic exchange of ideas about system requirements and features among potential users. Following the standard procedures for organizing a focus group, we limited participation of the test focus group to just one of the targeted potential users: graduate students. We thought that graduate students would offer sophisticated input, drawing on their expertise of conducting advanced research, as well as their valuable experience of teaching undergraduates. Enlisting Participants The biggest challenge we faced was enlisting participants—not an uncommon problem according to some of the literature we reviewed--and not to be underestimated when organizing a focus group. We put a lot of effort into recruiting participants: we posted flyers at a graduate student feminist conference; sent emails to the eighteen graduate student instructors (GSIs) of History 7B, a UC Berkeley introductory course in American history; sent an email to the entire graduate student body of the history department (about 100 people); contacted acquaintances and work associates, and called back graduate students we had previously interviewed individually. When only two people agreed to participate from all of these efforts, we decided that a more aggressive approach was called for. As her schedule permitted, Sally Thomas began to visit the History 7B GSIs individually during their office hours, discussing the project with them in person. This proved to be essential in enlisting participants—however, though many students expressed a willingness to participate, most had a conflict with the proposed meeting time, which had already been set. Only two 7B GSIs signed up for the focus group (and one would subsequently drop out the day before the focus group took place, when she came down with the flu). Personal contact with the graduate students proved to be valuable nonetheless. Sally Thomas used the occasion to request from those students who could not participate in the focus group to conduct a usability test of Suffragists Speak. We succeeded in enlisting five History 7B GSIs for usability tests using this follow-up strategy (discussion of usability test results follow, below). One additional History GSI for History 101, a senior thesis seminar, was also approached, and she agreed to conduct a usability test, too. That student was also kind enough to refer two of her undergraduate students to us, who also conducted usability tests. 1 Conducting the Focus Group We had aimed to involve at least six graduate students, that being the minimum number of participants suggested in the focus group literature we reviewed. Disappointed that such an extensive outreach process enlisted only three graduate students for the focus group, we nonetheless proceeded as planned. We had arranged to use a very nice conference room facility equipped with four computer workstations and a projection screen at the Graduate Services division of the Main Library, located at 208 Doe. To help make the participants feel comfortable, we also provided light refreshments (for which we had obtained prior permission from the Library staff). Profile of the Focus Group Participants Two men and one woman participated. "Sara": A Ph.D. candidate from the Architecture Department, she had done a lot of research at the Bancroft Library, using primary manuscripts, including diaries, of California suffragists. Her dissertation examines the gendered use of public space, focusing on suffragists in San Francisco from 1890 to 1917. She had some prior knowledge of Suffragists Speak, having been interviewed individually in the first round of the needs assessment. "Steven": Finishing his Ph.D. in History; his dissertation is an historical biography of a relatively obscure figure, Arthur G. Sedgewick (1844-1915). "Steven" served as a Graduate Student Instructor (GSI) for History 7B, and does creative consulting and interactive design in electronic entertainment and multimedia. "Dave": A second-year graduate student in history and currently a GSI for History 7B. The Focus Group Discussion We began the group by providing a brief overview of the system, and demonstrating on the projection screen the primary features of the site. Each of the graduate students sat at their own workstation during the presentation, following along, and asking questions. We then asked them to explore the site on their own, while the three of us observed, and answered additional questions. The individual participants became very engaged with the system, talking freely amongst themselves and with us—it was the perfect “ice breaker,” establishing a friendly rapport amongst all of us. We set up the conference tables so that the three web site developers sat directly across from the three graduate students. Sally Thomas acted as the primary moderator, and followed a prepared discussion guide (attached, see Appendix ____), which had ten questions. Joanne Miller and Rosalie Lack took notes, operated the tape recorder, and acted as back-ups to the primary moderator, ready to jump in if she missed any important cues. 2 The moderator started by asking the students to re-state their names and the focus of their research, and to identify if they had any prior experience conducting historical research on the Web, and, if so, to name particular sites they found useful. Some of the participants had used online sources for historical research. "Sara" named the "Valley of the Shadow: Two Communities in the American Civil War,"1--a hypermedia archive of thousands of sources including newspapers, letters, diaries, photographs, maps, church records, population census, agricultural census, and military records--as one she was particularly impressed with. Another student mentioned having used the Library of Congress's American Memory website. In response to the direction of the actual discussion, the moderator revised the discussion guide, primarily by dropping a few of the questions, so as to permit each of the students to respond in more depth to fewer questions. The discussion lasted about an hour and a half. The moderator asked the graduate students to begin with their overall impressions of the site. She then asked which resources should be given a priority for development, primary or secondary. She followed this with a question about which kind of primary sources they would like to see on the site. Prompted by the input of "Steven," who had experience developing online resources, the discussion then covered the user interface of Suffragists Speak, a topic that had not been included in the discussion guide. The moderator then turned attention to how the graduate students anticipated undergraduates would or should use the site, and some of the pros and cons associated with undergraduate use of online historical resources. Parenthetically to this question the moderator asked if the graduate students thought the site was usable in its current form. She then asked how they judge the credibility of sources. The moderator then asked them to brainstorm about how undergraduate students could be incorporated in the development of the site. The moderator's final question aimed at identifying the most important qualities of an online historical source. The discussion covered a total of nine questions, most of which had been included in the discussion guide, but some of which grew from the participants' own ideas of what was important to discuss. The moderator was careful to make the discussion flexible enough to accommodate the participants' interests. The participants became immediately engaged in the discussion, interacting nicely with each other and building off the ideas that each of them presented in turn. "Sara" and "Steven" were well on their way towards completing their dissertations and were the most outspoken, and typically the first to respond to the questions posed by the moderator. But when consistently prompted by the moderator, "Dave"—a second-year graduate student—was forthcoming and had many thoughtful and useful things to say, and the other participants left space open for him to participate in the conversation. 1 http://jefferson.village.virginia.edu/vshadow2/ 3 Focus Group Findings Overall Impressions Although the graduate students had many suggestions about how to improve the site, overall they were very positive about it. They felt that the site's structure was easy to navigate and that its introductory materials were useful. They identified one of the site's strengths as its incorporation of a multiplicity of sources (for example, letters, correspondence, and periodicals) that provided many different perspectives of the woman's suffrage movement. Content Development: Emphasis on Primary Sources The focus group participants unanimously identified primary sources as being the most important to develop, because primary sources are the most time-consuming and most expensive (in terms of photocopying costs) to find. They felt that with the aid of a good bibliography, secondary sources (books and scholarly journal articles) would be not only much easier to obtain from the library, but also that a printed format would be easier to read and to transport. "Dave" emphasized that because a movement is made up of individuals, resources that convey an individual's contribution to history are important. Students respond to history better when they can relate to the individuals of the past. "Sara," who was most knowledgeable about the history of woman's suffrage, commented that the material thus far available from Suffragists Speak carried a bias towards the national campaign to adopt a federal woman's suffrage amendment. She felt that the existing primary sources as well as the timeline and introductory materials did not do justice to important campaigns being led at the state level during the specified period, 1910-1920, including the successful woman's suffrage campaign of 1911 in California. She also suggested another valuable genre of primary sources, and one worth adding to the site: speeches. She argued that the rhetorical methods employed by suffragists provide a significant focus of analysis, and speeches are often difficult to locate. "Sara" also stressed the importance of including articles from several different regional areas. Breadth and diversity of coverage would add insight into the various strategies employed by suffragists, and would demonstrate how the public, as evidenced in newspaper editorials and letters to the editor, as well as biases in newspaper coverage, perceived the suffragists. Additionally, "Sara" noted the value of unposed photographs that showed suffragists in action, for example, street scenes. This kind of photograph can teach students a lot about the period and about a particular historical event. She also suggested using some of postcards available from the Bancroft Library. Several identified the importance of having a good subject and name index. "Steven" identified the Beinecke Archive at Yale University as having an extremely helpful names index containing not only the names of authors and recipients of correspondence, but also the names of every person identified in a document. (This, of course, is one of the most 4 expensive kinds of resources to produce, especially for a large collection, because it requires someone with a sophisticated grasp of the material to manually identify names and subjects.) Undergraduate Use of Online Resources All of the graduate students expressed concern about students plagiarizing from online resources, citing a widespread tendency of students to take material directly from the Internet, without attributing its source. Some of the participants had made previous recommendations that Suffragists Speak provide more interpretive summaries. For example, "Dave" initially recommended that the site provide a summary of the dominant trends in historical interpretation of the suffragist movement. On further reflection, however, the focus group participants acknowledged the danger of providing too much pre-digested information on the site. Although they acknowledged that this problem may decrease over time, as professors become more capable of recognizing plagiarism from online sources, they remained concerned about the ease with which students can copy and reproduce material from the Internet. After discussing the social consequences of offering historical sources online, the focus group participants concluded that it would be best for Suffragists Speak to emphasize the availability of the online sources at the library, or at the archive, providing an incentive to students to conduct further original research. In addition to providing a good bibliography (existing on the site) they felt that it would be important to provide recommendations throughout the site for additional materials, not reproduced on the site, but available from the library and/or archive. The graduate students also acknowledged that another downside of online resources like Suffragists Speak means that students do not experience the serendipitous process of discovering material. Because the newspaper articles and correspondence are already chosen, students do not experience for themselves the process of browsing through a source and happening upon something unexpected. Another problem is that the broader context is lost. For example, when an article is pulled from a newspaper, students lose the opportunity to see the placement of the article on the page and in relation to other news stories of the day. They also miss the advertisements, which convey important information about the customs and attitudes of the time period. Brainstorm on Undergraduate Participation in Development of Site Acknowledging that by providing primary historical sources online, users can bypass the active process of seeking out original sources from microfilm and archival repositories, the moderator asked the graduate students to consider how UC Berkeley undergraduates might be invited to participate in the development of the site. For example, students could contribute primary sources that they had personally retrieved from periodicals on microfilm, or from other non-copyright protected sources. The focus group participants liked that idea, and advocated the importance of students having the freedom to determine the focus of their research. "Sara" suggested that students could pick a theme 5 like suffragist parades, and dig up primary sources that related to that theme. The others noted that a potential problem with this approach is that the site would contain content that appeared random and not necessarily related. "Sara" thought it might be nice for the site to offer a platform for publishing student papers inspired by the online source material. She recalled that the Valley of the Shadow website provides links to student projects. Even though this recommendation contradicted previous concerns about providing convenient sources for plagiarism, "Dave" noted that if his 7B students knew they would be published online, they might feel an added incentive to write a good paper. Assessing the Authenticity of Digital Resources The moderator asked the focus group participants to identify how they evaluate the authenticity and credibility of online resources. The participants mentioned factors such as visual clues (e.g., logos and official names) and whether they were related to a credible source, like the Bancroft Library, for example. They suggested it would be important to show the affiliation of Suffragists Speak with the Bancroft Library, or a similarly respected library or department at UC Berkeley. Another indicator of the site's seriousness is the breadth of material available from the site. A large amount of material and obvious work put into a site lends more credibility to the site. Other important qualities included no typos, footnotes containing carefully constructed source citations, and a bibliography. A balanced editorial tone is also important. When the moderator asked them if they would like to have images of the actual documents to accompany the transcriptions, the participants said they would. User Interface "Steven" noted that the site could take more advantage of the "multi-navigation" capacity of the Web by providing multiple links or pathways to the various resources. For example, the short biographies of the suffragists could be linked from not only the "Meet the Suffragists" page, but also the "Oral Histories" page and the "Introduction to the Era" page, among others. "Steven" commented that some of the introductory quotes on the Home page included bracketed paraphrases, which were inappropriate for the user's first introduction to the site. Several suggested that the left navigation frame be shortened, so that it would fit on a standard-sized screen without the need for a vertical scroll bar. Some pointed out that when linking to a resource appearing near the bottom of the left frame, the user would not see it highlighted in yellow, as intended, without manually scrolling down the frame. This problem could cause the user to become disoriented. 6 The Dynaweb Interface The focus group participants identified a number of problems with the Dynaweb interface--primarily the search page. First, there needs to be an easy way to retrieve the search results--the results become difficult to retrieve once the user starts to review them. Someone also suggested that a "new search" button be made available from the search results page. Several commented that the footnotes windows should be smaller than the main window. When the user links to a footnote, it expands to the full size of the window, and it can be confusing to get back to the main text. A smaller footnote window would maintain visibility of the original window, and would be less disorienting. The Most Important Characteristics of an Online Historical Resource The final question was designed to help the designers identify which qualities and features should be priorities for the site. The moderator asked each participant to identify, among everything discussed that day, the "most important" characteristic of a good online historical resource. In one way or another, all of the participants emphasized the importance of an online resource providing access to information in ways that a traditional print medium cannot. For example, while "Steven" reiterated the importance of providing good navigation, he highlighted the value of a fully hyperlinked resource, and of providing a vehicle for users to give feedback. "Sara" noted the value of being able to provide access points to multiple types of resources, for example, allowing users to compare articles, letters, photographs, and newspaper articles--each reflecting a unique perspective on a particular historical event or theme. "Dave" commented that a Web resource should make history come alive. An interactive interface, coupled with features like photographs, audio, and moving images, can personalize history and thus engage students in ways that textbooks cannot. Evaluation of the Focus Group Despite there being so few participants, we were pleased with the outcome. Having a small group permitted each participant to speak at length on each topic, and also provided enough time for the participants to familiarize themselves with the Suffragists Speak site, making it possible for them to give more relevant feedback. "Sara" repeated some of the points she made in her individual interview, but the other participants triggered her to follow up on their personal insights--one of the main advantages of a focus group. Each participant's thought process is stimulated by the remarks made by the others, and therefore focus groups are thought by many social scientists to identify a broader range of issues than separate interviews with each individual. The enthusiasm and interest expressed by the group also served to inspire the development team, instilling a sense of excitement and giving us a boost of energy for the next design iteration. Our "hands-on" experience running a focus group also permitted us to learn some of the critical technical aspects of running a successful discussion. For example, we now know how important it is to have good sound recording equipment. A single unit with only one 7 microphone was inadequate to clearly pick up each of the participant's voices, making an exact transcription of the discussion difficult. In the future, it would be important to obtain a tape recorder with multiple microphones, each located directly in front of each speaker. 8