chapter two

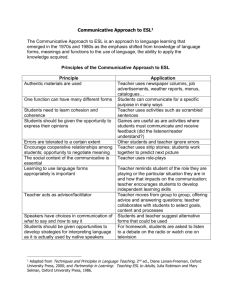

advertisement