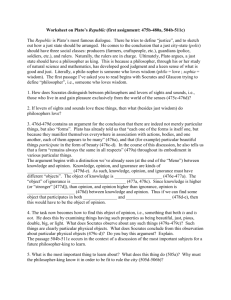

§3: SOCRATES` METHODOLOGY

advertisement