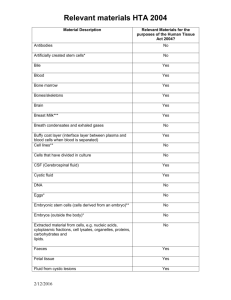

4. How HTA for medical technology works now in Australia

advertisement