Research Data Summary

advertisement

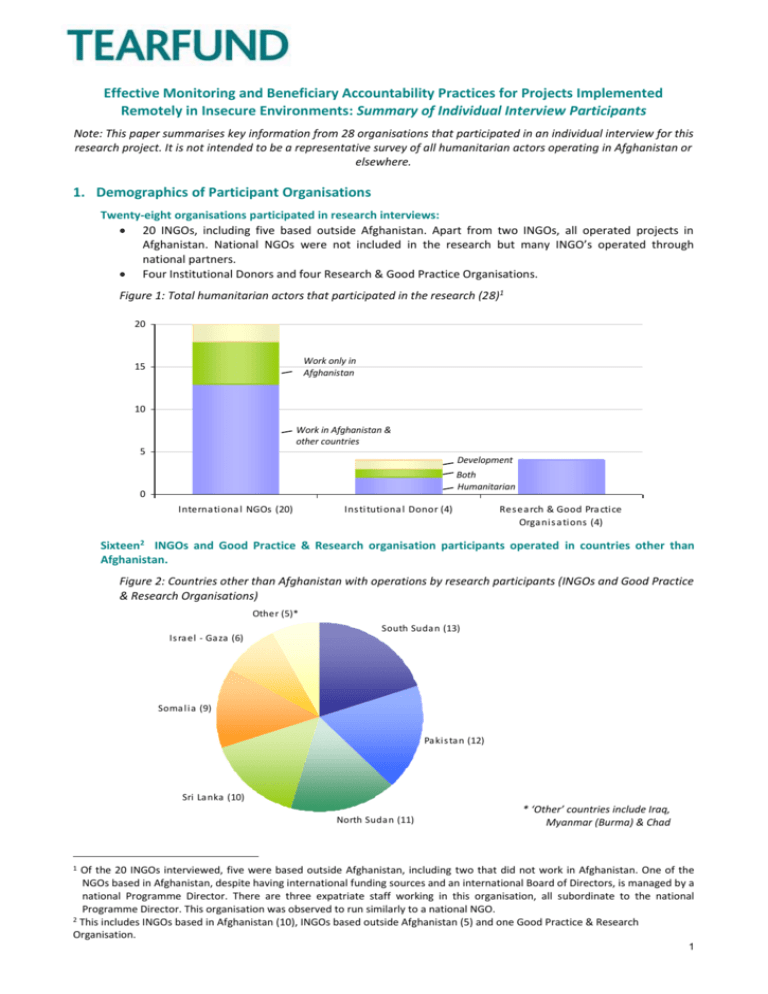

Effective Monitoring and Beneficiary Accountability Practices for Projects Implemented Remotely in Insecure Environments: Summary of Individual Interview Participants Note: This paper summarises key information from 28 organisations that participated in an individual interview for this research project. It is not intended to be a representative survey of all humanitarian actors operating in Afghanistan or elsewhere. 1. Demographics of Participant Organisations Twenty-eight organisations participated in research interviews: 20 INGOs, including five based outside Afghanistan. Apart from two INGOs, all operated projects in Afghanistan. National NGOs were not included in the research but many INGO’s operated through national partners. Four Institutional Donors and four Research & Good Practice Organisations. Figure 1: Total humanitarian actors that participated in the research (28)1 20 Work only in Afghanistan 15 10 Work in Afghanistan & other countries 5 Development Both Humanitarian 0 Interna tiona l NGOs (20) Ins titutiona l Donor (4) Res ea rch & Good Pra ctice Orga ni s a tions (4) Sixteen2 INGOs and Good Practice & Research organisation participants operated in countries other than Afghanistan. Figure 2: Countries other than Afghanistan with operations by research participants (INGOs and Good Practice & Research Organisations) Other (5)* Is ra el - Ga za (6) South Suda n (13) Soma l i a (9) Pa ki s tan (12) Sri La nka (10) North Suda n (11) * ‘Other’ countries include Iraq, Myanmar (Burma) & Chad 1 Of the 20 INGOs interviewed, five were based outside Afghanistan, including two that did not work in Afghanistan. One of the NGOs based in Afghanistan, despite having international funding sources and an international Board of Directors, is managed by a national Programme Director. There are three expatriate staff working in this organisation, all subordinate to the national Programme Director. This organisation was observed to run similarly to a national NGO. 2 This includes INGOs based in Afghanistan (10), INGOs based outside Afghanistan (5) and one Good Practice & Research Organisation. 1 INGO participants (20) interviewed in the research were mostly large and medium-sized. Figure 3: Size of INGO participants (19), based on number of expatriate and national/local employees in Afghanistan 12 National staff Expatriate staff 10 6 3 4 3 Large > 20 expa tri a te s ta ff > 200 na ti ona l s ta ff Medium 6-20 expa tri a te s ta ff 101-200 na ti ona l s ta ff Small 1-5 expa tri a te s ta ff* 1-100 na ti ona l s ta ff * Total INGOs sum to 19 because it excludes one INGO based outside Afghanistan that works solely through partner organisations. The INGOs has no staff in Afghanistan and programmes are managed remotely from UK Head Office. All twenty INGO participants have more than five years experience operating or supporting work in Afghanistan; ten have more than 20 years experience.3 The twenty INGO participants implement humanitarian and development projects across a wide range of sectors. The most common sectors were WASH, Livelihoods and Education. Figure 4: Types of projects implemented by 20 INGO participants4 Emergency Response (9) Food Security (6) Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) (12) Disaster Risk Reduction (3) Infrastructure Livelihoods (10) /Construction (3) Community Development (7) (x) = number of organisations with Agriculture National project type (6) Solidarity Prog. (3) Education (15) Psycho / Social (2) Capacity Building (3) Conflict Resolution / Peace (3) Women’s Rights (7) Legal Support Refugee (1) Resettlement (1) Good Practice & Research Organisation participants only identified projects in the education sector as having the potential to be successfully implemented and monitored under remote management. 5 Eighteen INGO participants implement projects in multiple provinces in Afghanistan; most work in four or more provinces. 3 This includes INGOs based in and outside Afghanistan with 6-10 years (7); 11-20 years (3); 21-30 years (6) and more than 30 years (4). 4 The 20 INGO participants include five based outside Afghanistan, of which two have no projects in Afghanistan. 5 Three of the four agencies interviewed were not in favour of remote management approaches. Their representatives spoke from experience of having seen programmes poorly implemented (or not implemented at all) due to remote management approaches. It was the general assessment of these three organisations that there would be no humanitarian and/or development sector that would lend itself successfully to remote management – all experiencing issues and problems. One agency remarked that Education might be more successfully implemented, whilst another commented that Basic Service Provision might be successfully implemented. The interviewer was given the impression that the type of sector implemented is not the key issue. Rather, the issue is in relation to the management approach itself, which is not supported by any of the three organisations. 2 Collectively, the four institutional donor participants support projects or humanitarian interventions in 33 out of 34 provinces in Afghanistan. The majority of participant INGOs operated projects in locations directly through their own staff. In approximately one-third of directly operated locations, the organisation had limited or no expatriate presence. Few project locations were operated through national partners, international partner or local community. No participant INGO’s operated projects through private contractors. Figure 5: Mode of Operation in INGO Participant’s Project Locations No. of Project Locations 50 40 30 20 10 0 Di rect Opera tions Di rect but Li mi ted Pres ence Na tiona l Pa rtner Int'l . Pa rtner Loca l Comm'y Financial incentives and R&R benefits for staff are implemented by 196 INGOs participants:7 Six have a voluntary expatriate staff base and do not pay expatriate salaries. All 19 pay salaries to national staff (relocated and local). All provide expatriate staff with R&R benefits. These also apply to relocated national staff in seven INGOs. Very few (2) apply R&R benefits to local staff. Half (9) provide a financial incentive to expatriate or relocated national staff working in insecure locations.8 Fewer (5) INGOs provide financial incentive to local staff working in insecure locations. 6 Total INGOs sum to 19 because it excludes one INGO based outside Afghanistan that works solely through partner organisations and has no staff in Afghanistan. 7 Several organisations emphasised that capacity building and an understanding of organisational ethos had a greater impact on staff retention and staff capacity than did organisational salaries, financial incentives and other benefits. These organisations often noted that there salaries were not comparable to larger organisations (e.g. UN and Government agencies), and that they preferred to focus on building capacity through training workshops and mentoring. 8 Several organisations noted that financial incentives were provided based on ‘hardship’ (e.g. for remote locations as well as insecure). It was also recognised by one organisation that the payment is made in view of ‘increased responsibility’ (and a review of the job description). One organisation also noted a creative approach to probation – easing staff into insecure project locations over a three month period of time. This was noted to have encouraged staff retention. 3 2. Remote-Management Of the 20 INGO participants, 14 have remotely managed projects. The main rationale that INGOs gave for adopting a remote management operational approach were 1) their organisational priority to work through national partners, and 2) a response to a general deterioration in security. Figure 6: Participant INGOs’ Rationale for Remote Management Operational Approach 25 * ‘Other’ includes cost effectiveness and forced circumstances given national political change. 20 15 10 5 0 Orga ni s a tiona l Pri ori ty to work through Na tiona l Pa rtners Genera l Deteri ora tion i n Securi ty Speci fi c Securi ty Inci dent Other* Rationale for Remote Management Operational Approach Of the 14 INGOs with remotely managed projects, less than half have an existing remote management policy or strategy in place, or criteria for ending remote management in insecure project locations9. Figure 7: Number of Participant INGOs with Remote Management Strategies & Criteria 20 15 Not in place* 10 5 0 Partnership Policy Remote Management Strategy In place Remote Ma na gement / Pa rtners hi p Stra tegy Cri teri a to End Remote Ma na gement Pa rtici pa nt INGOs wi th Remote Ma na ged Projects (14) *This includes 2 INGOs that plan to develop criteria for ending remote management, and 1 INGO that plans to develop a Remote Management Strategy. Two INGOs operate RM as standard practice. 9 It was noted that often while organisations did not have a formalised remote management policy that set out the criteria by which standard operations would resume or projects would close down, it was clear from discussions that many organisations had thought through the ‘return’ criteria (e.g. significant improvement in security). Those organisations which were able to demonstrate this thinking have been included in the ‘Confirmed Criteria in Place’ column. 4 One of the four institutional donor participants has an ‘official stance’ or policy related to remote management; two do not.10 Two-thirds of INGO participants have a programme wide and/or project specific security plan and risk analysis is in place, which most review quarterly or twice-yearly: The responsibility for reviewing and updating the programme wide and/or specific security plan and risk analysis is a joint effort between all staff and senior leadership. The majority (15) provide training on security plans and risk mitigation to expatriate staff and most to national and local staff. Five (all based in Afghanistan) provide no security training to staff. Figure 8: Number of Participant INGOs with Security Plan & Risk Analysis 20 Not in Place 15 Annually 10 In place, and reviewed: Bi-annual 5 Quarterly 0 Security Plan & Risk Analysis among all participant INGOs (20) The four institutional donor participants identified nine provinces in total that are ‘out of bounds’ for their personnel to visit.11 More broadly, most of the INGO donors identified by the INGO participants (see figure 11) are able to visit project sites or offices, however, in nearly all cases visits are dependent on security. Institutional donors who do not visit project sites or offices include: DFID; Scottish Government; USAID; OFDA; Danish Government; Jersey Aid. 10 The fourth institutional donor interviewed could not confirm whether or not there was a policy related to remote management. 11 It was noted that this fluctuates depending on the security situation of each province. Each institutional funding agency keeps a ‘watching brief’ on the security situation of the provinces in which they are supporting programmes. Decisions on when and whether to visit project locations will be made closer to the time of the visit. 5 3. Monitoring and Beneficiary Accountability in Remotely Managed Projects The most common issues identified by project stakeholders, relevant to monitoring remotely managed projects, were the affect on programme quality, compromises to effective and rigorous monitoring, limited capacity of personnel, and the security risk posed to staff and the community. Figure 9: Issues identified by all 28 participants relevant to monitoring and beneficiary accountability projects operating under remote management Programming Monitoring Compromises effective & rigorous monitoring (13) Programme Quality (14) Weak technical oversight (10) Capacity Staff & Security Limited capacity of personnel (own & partner) (11) Inaccurate data & reporting (11) Fewer opportunities to build staff capacity (6) Poor communication (10) Irregular access to projects (11) Increased pressure & expectation (social & political) (7) Increased security threat & risks (8) Fraud & Corruption (6) Key issues identified by INGOs, specific to staff and/or partner capacity to monitor remotely managed projects were the capacity to undertake robust monitoring of projects, to collect data, and to write reports (including in English). Figure 10: Staff and/or partner capacity issues related to monitoring & beneficiary accountability identified by INGOs12 Monitoring & Reporting Skills Management Skills Project Cycle Donor Management Relations & (4) Funding Cycles (2) Undertaking Robust Monitoring (12) Data Collection (12) Report Writing (9) Data Analysis (5) Understanding Concepts of: M&E (3) Beneficiary Accountability (3) Humanitarian Action Development (2) Action (2) People Management (1) 12 It was noted that issues are exacerbated due to high turnover of personnel. In Afghanistan, particularly in high insecure environments (and short-term emergency response projects) it can be difficult to develop and to retain capacity and institutional knowledge. Organisations varied in terms of the level of capacity building initiatives that were in place to build staff capacity. Some had developed internal structures which they invested in heavily. Others outsourced much of the training. Almost all organisations, however, recognised that this is a key area that they invest in (and one which they feel impacts their staff retention). 6 In response to the issues identified above, the most common practices adopted by INGOs include: Regular monitoring visits from head office to field location by objective personnel (16) Dedicated M&E capacity (team / coordinator) (13) Mentoring and training focus on organisational values and ethos (7) Intentional focus on capacity building and training of local / national staff (5) Good Practice & Research Organisation participants most commonly recommended the following practices to improve monitoring of remote managed projects: Stronger data analysis and reporting procedures (4) Intentional focus on ensuring that monitoring and evaluation systems are in place from the start of the project (3) Develop community relationship over long-term period (3) Institutional Donor participants most commonly recommended the following practices to improve monitoring of remote managed projects: Regular monitoring visits from head office to field location by objective personnel (4) Intentional focus on capacity building and training of local/national staff (3) Controls-based micro management approach (management and monitoring) (3) All institutional donors identified by participant INGOs set the framework for INGOs’ project monitoring and reporting. The level of involvement by each institutional donor in setting and following up on parameters for project monitoring and beneficiary accountability varies widely: For the majority of institutional donors, evaluations or mid-term reviews varies are ‘not always’ required and vary by project. A number of institutional donors however, do require evaluations or project reviews (AusAid; Dutch Govt; ECHO; Jersey Aid; SIDA; BPRM; International NGOs (collective); USAID; OFDA). Only two donors identified by INGOs did not require project evaluations or reviews. Figure 11: Level of involvement of institutional donors in project monitoring, as identified by INGOs Level of Donor Involvement: Limited Jersey Aid Norwegian Gov’t USAIS OFDA Scottish Gov’t Medium Afghan Gov’t CIDA Danish Gov’t DFID MFA Italian Gov’t BPRM Irish Aid Significant UN Agencies (various) International NGOs (various) Norwegian Embassy Highly Significant AusAid Dutch Gov’t EC ECHO SIDA Two-thirds of interviewees from INGOs believe that effective monitoring and adequate beneficiary accountability needs can be met in projects that are remotely managed (Figure 12). Half of the four interviewees from Good Practice & Research Organisations also believe this is possible. Three of the four institutional donor participants will fund partners that use remote management to implement projects; two currently do. One institutional donor participant is opposed to funding partners that will remote manage projects.13 13 It was confirmed by one agency that in terms of good humanitarian practice, they are opposed to remote management. A strong stance is taken within Afghanistan in opposition to remote management operational approaches and the donor is not currently willing to support the funding of any projects that their own personnel are not able to visit (as part of agency monitoring visits). It was acknowledged, however, that the agency does have to fund programmes within Somalia that are operated remotely. It was acknowledged that the funding agency currently has no other choice than to do this. 7 Figure 12: Number of all organisational participants in favour of, or in opposition, to remote management 20 15 10 5 0 INGOs (20) In favour Good Practice / Research Orgs (4) Oppose Institutional Donors (4) Undecided 8