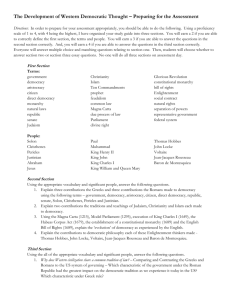

democracy`s third wave - Ministerio de Hacienda

advertisement