Magnets - Science Oxford

advertisement

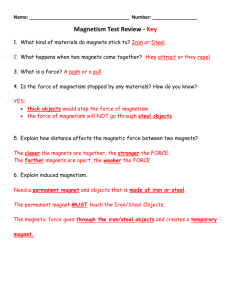

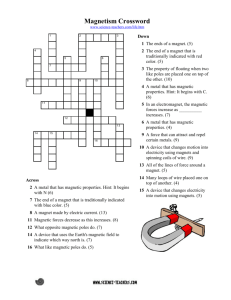

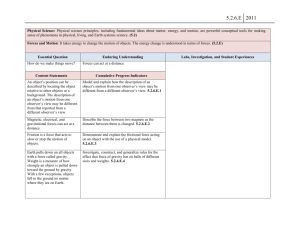

Oxford Brookes University Science department Magnetism It is wonderful to watch a child playing with a pair of bar magnets for the first time. The potential for awe and wonder is immense when decent magnets are used. It is just awesome not to be able to make the two magnets to touch each other, no matter how hard you try, or not to be able to stop them coming together when you turn one around. It is truly bizarre to feel these strong forces but not to be able to see anything there at all. It quickly demonstrates that there are forces of attraction and forces of repulsion between two magnets. It is also an example of forces acting at a distance – the force of repulsion or attraction is felt even when the magnets are not in contact. Primary children love magnets and once they have played with a good pair of bar magnets, it is a good idea to give each child one decent magnet to find out for themselves which things are attracted to a magnet and which are not. In fact only a few materials are attracted to a magnet: anything made of iron and this includes steel, e.g. safety pins and paper clips. The only other two metals that are attracted to a magnet are less common: cobalt and nickel. Materials that are attracted to a magnet are called magnetic materials. N.B.. Not all metals are attracted by a magnet. Children may find this strange. Magnetic materials are only ever attracted to a magnet – never repelled. Forces of both attraction and repulsion only occur when there are two magnets. So it is great fun for a child to experience forces acting at a distance, e.g. a magnet pulling something towards it or pushing away another magnet which it is not actually touching. However, magnets will gradually lose their magnetism over time so it is always worth checking the usual school magnets before giving them to the children – they need to be strong enough for the children to be able to feel these forces. Magnets vary in strength. Some are very weak and produce weak forces of attraction and repulsion; others are very strong. Strong magnets are used in hospitals, for example in MRI scanners (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) and also in areas of physics research. It is necessary to remove any watches before entering the vicinity of these research magnets or the insides of the watch may be pulled apart by the strong magnetic field! Most magnets used in primary schools are very weak but it is possible to purchase decent ones these days, including a ‘Magic Penny Kit’ which contains a very strong pair of magnets. It is generally not a good idea to place magnets in the vicinity of computers, credit cards, photocopy cards etc. as these all contain magnetic material which can be affected adversely. Oxford Brookes University Science department It is worth keeping the old magnets though and setting the pupils the challenge of finding the strongest magnet or putting a set of magnets in order of strength. There are a number of ways of doing this and it is best to leave the children to design their own fair test. They could, for example, find out how many paper clips can be hung in a chain under each magnet or measure how close to a paper clip the magnet needs to be placed before the clip moves towards it because of the force of attraction etc etc. Magnets occur naturally and their name comes from the ancient Greek town of Magnesia, near which the first naturally occurring magnets were found. They were called lodestones and consist of iron oxide. Tradition has it that Thales of Miletus in about 550 B.C. was the first philosopher to describe the phenomenon .of magnetism. They must have seemed magical to ancient people. Magnets became more than a curiosity when it was discovered that a steel needle stroked by a lodestone became magnetised, i.e. the needle became a bar magnet. If the bar magnet is then allowed to swing freely, one end will always face north and the other south (or nearly so). This was obviously very important for navigation and remains so today. They were in use in Europe as early as the twelfth century. A compass is just a bar magnet that is able to pivot freely. So when a bar magnet is free to pivot: one end faces north and is called the ‘north seeking’ or north pole. the other end faces south and is called the ‘south seeking’ or south pole. It is then possible to show that: Like poles repel Unlike poles attract i.e. 2 north poles repel each other and a north and south attract etc. As we have said, it is so important for children to experience the awe and wonder of magnets. At the age of five, Albert Einstein became fascinated by his father's pocket compass, intrigued by invisible forces that caused the needle always to point north. Later in life, Einstein looked back at this moment as the genesis of his interest in science Magnetic north and geographic north do not quite coincide and so this needs to be allowed for when using a compass. Oxford Brookes University Science department The Earth has its own magnetic field which causes compasses to behave as they do. A very simple picture of the Earth’s magnetic field can be obtained if it is imagined that a large bar magnet is within the earth. This is not actually the case but it is helpful to understands that a compass acts as though this were true. The earth’s magnetic field may be due to electric currents circulating in the earth itself. If iron filings are scattered around a magnet, it is possible to see a pattern However, iron loose filings are very messy and not really recommended for use in primary schools. It is now possible to buy iron filings which are contained in a suspension and are much easier to use. This demonstrates the fact that a magnet influences the area around it and this area of influence is called the magnetic field. Whilst this is not on the primary curriculum, it is another demonstration of the fact that magnetism can act over a distance, so magnets can exert forces on objects with which they are not in contact.