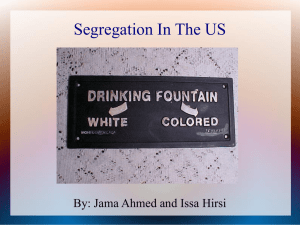

Racial Segregation Processes and Policies in the

advertisement