HISTORY OF ENGLISH LITERATURE: AN OVERVIEW

advertisement

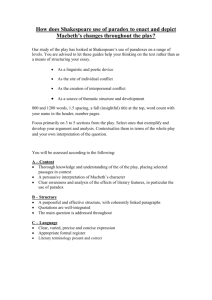

HISTORY OF ENGLISH LITERATURE: AN OVERVIEW Dear Students, The purpose of this course is to encourage you to gain an insight into, and broad awareness of, the development of English literature from its perceived origins in the ninth century until the end of the nineteenth century. Attention will be paid not only to influential writers and movements, but to themes such as the influence of Greek mythology, religion, politics, and the rôle of Ireland. Some writers, poets and playwrights considered are Langland, Chaucer, Malory, Marlowe, Shakespeare, Pope, Swift, Wordsworth, Keats, Byron and Dickens. I apologise to the many superb but deceased writers whom I cannot include in this all too brief summary, and even to those whom I have included, for treating them somewhat summarily. The course takes the form of a series of lectures, which form but the tip of the iceberg, providing you with a door to your own research and study. You are encouraged to share the results of your studies, helping not only your fellow students, but the lecturer. We are, after all, in the same boat, even if I am at the helm. Evaluation will be by unseen short written essays. I shall provide some examples of examination questions at the end of this hopefully helpful guide. The course kicks off by considering English literature’s fairly late entry into the world of writing, a fact explained by the destruction of Roman Britain by barbaric German tribes, and a series of subsequent invasions that made it difficult to standardise the language and create high-level writing until the late Fourteenth Century. Naturally, once the area later to be known as England began to settle down during the reign of Alfred, priests began to translate Latin texts into Anglo-Saxon/Old English. Churchmen had an advantage, since they were literate. Gildas, born around 500, wrote The Destruction and Conquest of Britain in Latin, while Bede (who died in 735) wrote the Eclesiastical History of the English People, also in Latin. They cannot therefore be included as writers using Old English exclusively, although their works were later translated into Old English. Although the story of Beowolf is the longest 1 known epic poem in Old English, it is a Scandinavian tale dating from the Eighth Century. English literature begins to define itself more clearly following the Norman invasion, which resulted in a minor transmogrification, with the importation of thousands of French words. By 1150, we can therefore identify the result, known as ‘Middle English’. Here we have two superb works, one by the poorish priest, William Langland (1332-1400), Vision of William concerning Piers the Ploughman, which is a religious journey through morality, mentioning the seven Deadly Sins of sloth, avarice, anger, gluttony, lust, envy and pride, concluding that it is better to be good than rich. In contrast, his counterpart, Geoffrey Chaucer (1343-1400), was well off, working in senior government and as a diplomat, going on various European trips. He is said to have met Petrarch or Boccaccio. Certainly, his renowned Canterbury Tales seems to betray elements of Boccaccio in its earthiness and methodology. He wrote several works, including Troilus and Cressida, and The Legend of Good Women. The next well-known piece of work with which we deal is Mallory's (c. 1405-1471) Morte d’Arthur, extrapolated from old French and some English tales, and written in early modern English. One can truly say that it has been impregnated in the British national consciousness. Many scholars think that Arthur was a Romanised Briton who fought against the German invaders. He probably was, but in the centuries of literary Chinese Whispers since then, the tale has probably been considerably embellished. Before now moving into the Sixteenth Century, let us mention that the invention of printing, which was taken up by William Caxton in 1476, had a big impact on literature, in that it became more widespread among the ordinary population. Edmund Spenser’s (1552-1599) Faerie Queen is an example. Notwithstanding criticism that he wrote it to gain favour with Queen Elisabeth (he was awarded some good positions), it is a thrilling piece of work, as the following shows: ‘The steely head stucke fast till in his flesh, Till with his cruell clawes he snatcht the wood, And quite asunder broke. Forth flowed fresh A gushing river of blacke goarie blood, 2 That drowned all the land, whereon he stood; The streame thereof would drive a water-mill.’ Spenser was educated at the Merchant Taylors’ School (which my school, St. Pauls, founded in 1509, used to beat at rugger) and Cambridge, living most of his professional life in Ireland, where he was Secretary to the Lord Deputy. His home was burnt down in the 1598 rebellion, so at least some of his life was exciting. One is inclined to wonder whether the Celtic throb of Ireland influenced, and stimulated, his writing. And then of course we come to William Shakespeare (1564-1616), prolific writer of plays and sonnets, son of a dealer in gloves and wool, who had his own theatre company. He was well versed in the classics, having attended Stratford Grammar School. It was indeed the introduction of Grammar Schools during the reign of Henry VIII that had stimulated literature and learning, as well as the influence of the Renaissance, already visible in Chaucer. Consider this, from the Merchant of Venice: ‘All that glisters is not gold; Often have you heard that told: Many a man his life hath sold But my outside to behold: Gilded tombs do worms unfold.’ Shakespeare, so very influenced by classical Greece and Rome (as were many before and after) invented thousands of new words and phrases such as ‘tower of strength’ and ‘assassination’. It was not until the German Romantics elevated him to an almost godlike literary status that he was to become known world-wide. He has generated controversy as well as fame. Samuel Johnson wrote: ‘Shakespeare is so much more careful to please than to instruct that he seems to write without any moral purpose’, while the great Tolstoy wrote of ‘repulsion, weariness and bewilderment’. Strangely, no original work by Shakespeare is known to have survived. Some even think that he may not have existed. 3 Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593) is hewn from the same literary stone as Shakespeare, even having contributed to some of the latter’s plays. A sort of literary version of Caravaggio, he was stabbed to death at the age of twenty nine, not long after the issuing of an arrest warrant, possibly for blasphemy. It is possible that, had he lived longer, he would have been at least as well known as his homologue Shakespeare. Consider this, from his Dr. Faustus: ‘Was this the face that launched a thousand ships, And burnt the topless towers of Ilium? Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss. Her lips suck forth my soul: see where it flies!’ It is not difficult to see why, with writers such as Marlowe and Shakespeare, the Sixteenth Century was that of the dramatists. As we move on to the end of the Sixteenth Century and into the Seventeenth, we come to Ben Jonson (1572-1637 (not to be confused with Samuel Johnson).Although he was a pupil at Westminster School, he managed to be a bricklayer for a time, like his father, as well as a soldier. He is best known for his masques, which induced a gay atmosphere of humour, costume, dancing and music. Drama then went into decline, owing to the rise of Cromwellian Puritanism. In the meantime, the essay had begun to flourish as a literary form, in the guise of, inter alia, Francis Bacon (1561-1626), also considered to be an early empiricist philosopher. Although this senior government figure, awarded a lordship, was considered by some to be a bit of a toady, like Spenser, he really was rather good. His most famous essay is The Advancement of Learning. He seems to have believed that knowledge is power. Now we bring in Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), who studied at Oxford. His most well-known epithet is that Man’s life is solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short, and his ‘Leviathan’ is a good treatise on political philosophy. He has been claimed, unfortunately in my view, by many international relations theorists to have been a promoter of political realism/power politics, when in fact his main interest was in how to best run a country at national level. He was a true intellectual, translating 4 Thucydides’ Peloponnesian Wars, and the Iliad and Odyssey. Like so many English literary people, he was almost helplessly influenced by Greece. We now come to a spot of poetry (although Shakespeare’s sonnets surely also qualify as such). Let us sum up John Donne, an ex-Roman Catholic, Cambridge man and lawyer, (1572-1631) with the following: ‘Tis time, ‘tis day; what though it be? O wilt thou therefore rise from me? Why should we rise because ‘tis light? Did we lie down because ‘twas night? Love, which in spite of darkness brought us hither, Should despite of light keep us together.’ Then along came the ‘Cavalier poets’, one of whom, Robert Herrick, wrote Counsel to Girls: ‘Gather ye rosebuds while ye may, Old time is still a-flying. And this same flower that smiles today Tomorrow will be dying.’ These gay and carefree chaps had a hard time during the Cromwellian dictatorship. Old Pauline poet John Milton (1608-1674), a Cambridge man, thrice married, torn between freedom and convention, is perhaps best known for Paradise Lost. Like many a well-heeled Englishman, he went on the ‘Grand Tour’ of Europe, even meeting Galileo. His works are clearly influenced by Greece. Like Chaucer and Spenser, he held senior positions, but was caught in the crossfire of Puritanism (he worked for Oliver Cromwell) and the Restoration. Let us sum up this sensitive and perhaps tortured man with the closing words of one of his sonnets, in which he describes a dream about one of his dead wives: ‘Her face was veil’d; yet to my fancied sight 5 Love, sweetness, goodness, in her person shined So clear, as in no face with more delight, But oh! As to embrace me she inclined, I waked – she fled – and day brought back my night.’ He clearly loved her and missed her. You will probably have begun to see that there is often a relationship between politico-religious developments and literature. Milton, for example, was imprisoned for a while at the Restoration, for having been close to the despised Cromwell, while the poet John Dryden (Westminster and Cambridge) also lost his stipend under William of Orange, for having converted to Roman Catholicism. Now we move to prose and the diary writers, the most famous of whom is Samuel Pepys (1633-1703), whose description of the Fire of London in 1666, as well as life in the Seventeenth Century is realistic. But let us not forget John Evelyn, who wrote a much longer diary. Now we come to a quintessential English book, by Isaac Walton (1593-1683), The Compleat Angler, one of the best books about angling ever written. It is somehow about much more than angling, about the pleasures of leading a contemplative life, as can be seen from its alternative title. John Bunyan (1628-1688) was a very different kettle: the son of a tinker, he had a meagre schooling, and learnt to write thanks mainly to the Bible. Because he was a bit of a Christian fundamentalist (a Baptist) and preacher, he was imprisoned for twelve years at the Restoration. His most well-known work is The Pilgrim’s Progress, full of morality, but also humour. So we now leave the Seventeenth Century, and come to another of the giants of English literature, Jonathan Swift (1667-1745), born in Dublin of English parents, a man influenced by religion, politics and Ireland, and even women. He was a trained priest, spending much of his life in Ireland, ending up as a champion of freedom for Ireland. He was a superb political satirist, making the political pamphlet almost an art 6 form. He is best known for Gulliver’s Travels, a scathing attack on political hypocrisy. Edmund Burke (1729-1797) is our next choice. He was an important political philosopher, and is considered to be the founder of English Conservatism. Although a supporter of Irish and American independence, he turned against the French Revolution, because of its excesses. His contemporary, Samuel Johnson (1709-1784) was a professional writer (he also married a rich widow) and a witty man, writing for example, that he who made a beast of himself got rid of the pain of being a man. Another very witty literary chap was Alexander Pope (1688-1744) who, as a Roman Catholic, was not allowed to vote or hold public office. His best known work is the poetic Essay on Man, a sensitively written moral tract on how Man should accept God’s mysterious ways. As regards Pope’s pithiness, consider this: ‘A little learning is a dang’rous thing; Drink deep, or taste not the Pierian Spring’. We can see from this, that like so many writers, he was influenced by ancient Greece. He also translated the Odyssey. Let us mention (I wish that we had more space) the group of poets known as the ‘Transition Poets’, such as James Thompson, Thomas Grey, William Collins and William Blake. They tended to concentrate on Nature and the metaphysical. As for the amazing Scotsman, Robert Burns, he is not easy to categorise, but certainly he was of a Romantic bent, and usually wrote his poetry with Scottish pronunciation. Several of his poems were used as lyrics for songs. Drama was popular: the Irishman Richard Sheridan (1751-1816), for example, wrote The Rivals, which includes a character by the name of Mrs.Malaprop, who had problems with finding the correct word. Thus today, ‘saying ‘alligator’ instead of ‘allegory’ (because one does not really know!) is a ‘malapropism’. The novel was now coming into being, the seeds having been sown by the likes of Bunyan and Swift. Daniel Defoe’s (1660-1731) Robinson Crusoe (based on a true 7 story, as are many novels), about a castaway, is still very popular. He wrote various other, more fictional, novels, as well as various pamphlets. He was also a journalist. Another good novelist of the time was Henry Fielding (1710-1768), with his somewhat naughty and bawdy Tom Jones, about a young servant being wooed by his lady employer. It is nevertheless a good reflection of life at the time. The Industrial Revolution then began to make its social impact on the country. Factories were being built, coal mine mines dug, and people dragooned into working mechanically for hours on end, with a good deal of exploitation of women and children. The so-called ‘Protestant work ethic’ ran rampant. The Seven Years’ War had resulted in an enormous and expanding British Empire. For many, greed became the order of the day. It is now that the Romantics came to the fore. Romanticism probably has its origins in the Sturm und Drang movement, which was a reaction to the excesses of the Enlightenment, with its over-interpreted Classical forms, and the Age of Reason, which lacked wild and free spirituality in its scientific, rational pedantry. Some of the ideas behind the French Revolution helped. Most of the British Romantics traveled in Europe, and were clearly heavily influenced by Greek mythology. In Britain, it also manifested itself as a reaction to the greed of the Industrial Revolution. William Wordsworth (1770-1850) was surely one, but more conservative and controlled in nature than some of his homologues, such as Byron. He was a Cumbrian who loved nature, and a Cambridge man attracted by the ideas of the French Revolution, who was good enough in his day to become Poet Laureate. Consider this (if you feel like it): ‘She dwelt among the untrodden ways Beside the springs of Dove A maid who there were none to praise And very few to love. A violet by a mossy stone Half hidden from the eye! - Fair as a star, when only one is shining in the sky. 8 She lived unknown, and few could know When Lucy ceased to be; But she is in her grave, and, oh, The difference to me!’ William’s friend, Samuel Coleridge (1772-1834) was also rather good, and is best known for The Ancient Mariner. Here is an extract: ‘Day after day, day after day, We stuck, no breath nor motion; As idle as a painted ship Upon a painted ocean. Water, water everwhere, And all the boards did shrink; Water, water everywhere, Nor any drop to drink.’ Our next three Romantics all died young, and not exactly naturally, in their good time, the fate of many a fast liver. John Keats (1795-1821) had women problems, nevertheless qualifying as - what one would think would be a down-to-earth - ) apothecary-surgeon. Here are two lines from Ode to a Nightingale: ‘My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk.’ The poem is laden with references to Greek things. He is also well-known for Ode to a Grecian Urn. His father died when falling off a horse when Keats was eight, and his mother when he was fourteen. Percy Shelley (1792-1822), who supported freedom for the Irish, managed to struggle on until he was thirty, then drowning in a sailing accident in Italy. Like several Romantics, he left the – for them – intellectually stifling shores of England for Italy. 9 He had various colourful relationships with women (one of whom drowned herself). Here are two of his lines: ‘ Drive my dead thoughts over the universe Like withered leaves to quicken a new birth!’ And so we come to Lord Byron (1788-1824), educated at Harrow and Cambridge. He was the epitomy of freedom, a scourge of the hypocritical part of the English Establishment, and was loved more in Europe than England. He found England too insular and was an embarrassment to bigots and the small-minded. Leading a very colourful life with women, he divorced, but managed to sire a daughter. Known for, inter alia, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, and Don Juan, some of his scintillating lines are: ‘I stood in Venice, on the Bridge of Sighs, A palace and a prison on each hand: I saw from out the wave her structures rise As from the stroke of the enchanter’s wand: A thousand years their cloudy wings expand Around me, and a dying glory smiles.’ Apart from infuriating the English Establishment with an attack on the barbaric removal of the ‘Elgin Marbles’ from the Parthenon (see The Curse of Minerva), he died of a violent fever fighting for Greek independence. It was not until 1969 that his remains were buried in Poets’ Corner of Westminster, an example of considerable pettiness on the part of the tawdry part of the Establishment. You may by now have noticed that no females have been mentioned. This is because women do not appear to have been that hot at writing, for many socio-economic reasons. Mind you, let us not forget the inimitable Sappho! Jane Austin (1775-1817) is surely one of the greatest English writers, with her Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility, Emma, Mansfield Park, and Persuasion. Her expertise was in handling rough and passionate topics, usually about relationships between men and women in 10 the higher classes, with tact and delicacy. I think that she managed to combine precision with lightness, a rare gift. Pride and Prejudice begins: ‘It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife. However little known the feelings or views of such a man may be on his first entering a neighbourhood, the truth is so well fixed in the minds of the surrounding families, that he is considered as the rightful property of some or other of their daughters.’ The Bronte sisters, Charlotte (1816-1855), Emily (1818-1848 and Anne (1820-1849) were influenced by Byron, and managed to slightly shock the Establishment, with their passionate descriptive writing about, inter alia, love affairs. Charlotte is best known for Jane Eyre, Emily for Wuthering Heights, and Anne for Agnes Grey. They were veritable pace-setters, since there are today a number of female writers who concentrate on stories of romances, albeit not at the same high literary level as the three sisters. Moving well into the Victorian Age, we come to (Lord) Alfred Tennyson, famous for his epic The Charge of the Light Brigade, a depiction of a bad military decision in the Crimean war. Here is an extract: ‘Cannon to right of them, Cannon to left of them, Cannon in front of them Volleyed and thundered; Stormed at with shot and shell, Into the jaws of death, Into the mouth of hell Rode the six hundred.’ We begin to end this overview with a monument, Charles Dickens (1812-1870), an amazing fellow, who even spent some time when a boy in the workhouse, while his father was in debtors’ gaol. The experience left a lasting impression, and he was most 11 critical of the affects of the Industrial Revolution. Like many writers of the day, his novels were often serialized in cheap magazines, which meant a wide readership. He was an expert in description, especially of people. George Orwell was to write that he seemed to have succeeded in attacking everybody and antagonizing nobody. It could be that his sometimes humorous approach helped. He did however irritate the Americans with his American Notes and Martin Chuzzlewit, by mentioning their lawlessness and rapacity. He was a prolific writer: who has not heard of Oliver Twist, Great Expectations, David Copperfield and A Tale of Two Cities? Consider this extract, from Hard Times: ‘It was a town of red brick, or of brick that would have been red if the smoke and ashes had allowed it; but as matters stood, it was a town of unnatural red and black like the painted face of a savage. It was a town of machinery and tall chimneys, out of which interminable serpents of smoke trailed themselves for ever and ever, and never got uncoiled.’ Penultimately, we have Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936), of Jungle Book fame. It is he who spoke of ‘the White Man’s burden’ (meaning black and maybe brown people), thus attracting accusations of racism many years later. But that’s the way it was in those days when Britain was on top of the world, and when various rational types, such as Buffon and Darwin, had rather strongly suggested that black chaps were inferior to white ones. I am unsure as to their views on whether the same applied to women. We end with the ‘Pre-Raphaelites’, a group of writers led by the Anglicised Italian Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882), influenced by early Sixteenth Century Italian painting and literature. That, students, is the end of our brief glimpse at the history of English Literature. Clearly, knowing about developments in Britain throughout the period with which we have dealt will help you to see the relationship between political, religious, social and cultural life. My Britain: Country and Culture courses should help there. One thing to remember is that the vast majority of writers read other writers, and that in a sense they are often influenced, perhaps without realising it. 12 Beware of over-categorisation: if we escape from it, we may spot traces of romanticism far earlier than the main movement began: ‘I walked along a stream for pureness rare’, wrote Marlowe, while Donne wrote: ‘A teardrop that encompasses and drowns the world’. Typical questions from my past examination papers have been: ‘ “English Literature of the Sixteenth to Nineteenth Centuries cannot be understood except in the light of Greek mythology.” Explain this contention.’ ‘What, in your view, were the chief characteristics of the Romantics, and why did they have such characteristics?’ ‘What do you think influenced Jonathan Swifts work?’ ‘Was Lord Byron the same kind of Romantic as Wordsworth?’ It goes without saying, almost, that merely learning the above few pages, parrotfashion, will not be sufficient to pass the examination: they represent only a skeletal outline. I shall immediately see through any examination paper that appears to rely only on this brief guide. Most marks will be awarded for evidence of originality and thinking, as well as of knowledge. Have fun! Yours faithfully, William Mallinson 28 October 2011, in the year of our Lord. 13 14