Word - My Illinois State

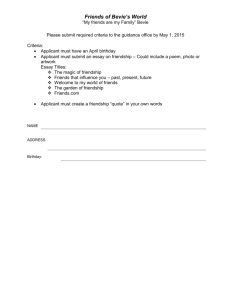

advertisement