china_rural_exodus.doc

December 21, 2004

THE GREAT DIVIDE | A MISSING GENERATION

Rural Exodus for Work Fractures Chinese Family

By JIM YARDLEY

HUANGHU, China - Yang Shan is in fourth grade and spends a few hours every day practicing her Chinese characters. Her script is neat and precise, and one day, instead of drills, she wrote letters to her parents and put them in the mail.

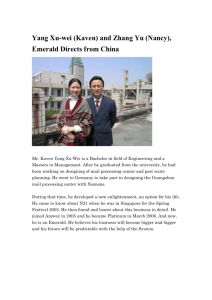

Miranda Mimi Kuo for NYT

Yang Shan’s father and mother have left to work in cities far away, and she is being raised by grandparents.

"How is your health?" she asked.

Shan, who is 10, then added a more pointed question: "What is happening with our family?"

Her parents had left in March. Their absence was not new in Shan's short life. Her father,

Yang Heqing, has left four times for work. He is now in Beijing on a construction site.

Her mother, Ran Heping, has left three times. She is in a different city as a factory worker.

Over the years, Shan's parents have returned to this remote village to bring money and reunite the family. They leave when the money runs out, as it did in March. Her father had medical debts and needed cash to see another doctor. Shan's school fees were due, and her grandparents also needed help.

"I think they are suffering in order to make my life better,"

Shan said of her parents. She added a familiar Chinese expression: "They are eating bitterness."

For the Yang family and millions of others in the Chinese countryside, the only way to survive as a family is to not live as one. Migrant workers like Shan's parents are the mules driving the country's stunning economic growth. And the money they send home has become essential for jobless rural

China.

Yet even that money is no longer enough. Migrant wages have stagnated, education and health costs are rising, and the rural social safety net has collapsed - a crushing combination

China's Great Divide

Jim Yardley and Joseph

Kahn examine the gap between the rural poor and urban rich.

• Part Five: Suddenly

Landless

• Part Four: Competing for

Souls

•

Part Three: Managing

Rebellion

• Part Two: Rural Wastelands

• Part One: Education

The Great Divide

A Missing Generation

Articles in this series are examining the widening gap between the rural poor and urban rich that has made

China, the world's fastestgrowing economy, also one of its most unequal societies.

that is a major reason the income divide is widening so rapidly in China at the expense of the rural poor.

Migration also has meant that urban and rural children in China are growing up in starkly different worlds. In cities, upwardly mobile couples call their precious only child xiao taiyang, or "little sun," as in center of the universe. Children are indulged with clothes, toys and snacks: childhood obesity is a new urban ill.

In the countryside, the new vernacular phrase is liu shou, or "left behind" child. Millions of children like Shan are growing up without one or both parents. Villages often seem to be missing a generation. Grandparents work the fields and care for the children.

"We are a triangle, three people in three different places," said Mr. Yang, 36, the father.

"The pain of missing one another is very difficult. All parents are the same in this world.

All parents care about their children."

But Shan's parents, strapped with debt and obligation, are among the untold millions of people in rural China caught in a brutal cycle. Studies show that medical costs are the leading reason that people fall into poverty in China. Many city residents still have some health benefits, but peasants now fall under a pay-for-service system. Sickness can mean bankruptcy.

Mr. Yang went to Beijing in part to earn enough money for medical treatment. He was warned four years ago that he needed treatment for prostate problems, but he could not afford it. Now, his health has worsened on his construction job. He has missed days and is jeopardizing the pay he needs to see a doctor.

His wife, Ms. Ran, 33, wants to visit her daughter in February for the Lunar New Year, when migrant workers traditionally go home. But she said her factory in the city of

Baoding will fine her $72 - roughly six weeks' pay - if she does not work straight through to July. Shan's school fees are due soon, and the family needs more money.

Shan has never left this village in mountainous central China, a few hours' drive from the

Three Gorges along the Yangtze River. She is still a child, but she understands the pressures on her family and how her own future depends on getting an education. She grew worried when the school began asking for next semester's tuition.

"I love school," she said.

A Desperate Village

The students in Shan's fourth grade class rose in unison as the teacher, Du Nengwei, tapped his pointer against his desk to start the lesson.

"Hello, teacher!" the children shouted dutifully in early December as Mr. Du, his eyes magnified through thick glasses, signaled for everyone to sit down. The children began

shouting out memorization drills, and the sounds of rote drilling rose out of other classrooms, as noisy as squawking birds.

The village school, the focus of so much hope, is little changed from a century ago. The dirty, whitewashed building is made of mud brick and concrete. Shan's classroom has no heat or electricity. Light comes from two small windows.

Mr. Du said 8 of his 14 students had at least one parent who is a migrant worker. He knows that parents leave in order to pay tuition, about $50 a year for families that often live on less than $300 a year. School, even this school, is their only chance, he said.

"Some say they want to be a driver, a scientist or a teacher," Mr. Du said. "But nobody wants to go on being a farmer." Of Shan, he said, "she studies very hard and does well."

She usually ranks second or third in the class. At home, she studies as much as three hours a day. She said she wanted to advance to middle school, then high school, even college.

"The more schooling I have, the more knowledge I have," she said.

Her home is a mud-walled communal house built more than a century ago during the

Qing Dynasty. Her grandparents sleep in one section, her aunt and younger cousin in another. Shan sleeps alone in two unheated rooms converted from a small barn. Her room is above the pen with the family's three pigs. Her parent's empty room is over the open pit that is the communal toilet.

"I'm not scared," she said. She has painted her colorless wooden shutter with the Chinese characters for "wealth" and "prosperity."

Her grandfather, Yang Xianglin, 72, said his three sons each contributed $150 a year to support the family. Two of the three are migrant workers; the third just returned home from a migrant job. But the money is not enough, so the grandfather must borrow from other relatives.

Shan knows she is poor, but does not seem to feel poverty's sharp sting. Asked if she has any toys, she brightened and showed off two tiny plastic figurines and a single silk flower. Her parents cannot afford more, though her mother stitched her a pink sweater.

"She misses them always," her grandfather said. "She keeps asking, when will her parents come home?"

Nearly every family in Shuanghu has had someone leave. Local wages are as low as $1 a day; a migrant can make $5 or more. A few fortunate families have built concrete homes with migrant money.

"We have more freedom now than when we had a communal life," said Lei Jinchen, 53, a neighbor whose two sons work at the same factory as Shan's mother. "We can now go out and find work. But we only have enough to feed ourselves. That's it."

Central government leaders often boast of new programs to benefit China's poorest villages. One national program called for farmers to hand over land for reforestation in exchange for annual payments. In 2002, Shan's grandfather surrendered two-thirds of an acre for promised payments of $65 a year. As yet, he and other farmers have received nothing.

Shuanghu was also designated for special antipoverty assistance, and about 50 families - including the Yangs - were named poverty households eligible to divide a $2,500 annual fund, or about $50 per family. But again, the Yangs and others have gotten nothing.

"Not many benefits get down to us," Mr. Lei said. "Local governments skim most of the money off."

So what remains is migrant work for the young and farming for the old. The mountainous landscape is impressive, but only narrow strips of land can be used for farming. In early

December, Shan left for school one morning, and her grandparents walked up a rocky hillside toward their small plot.

The frost had lifted, and the grandmother, Hu Yangui, 65, squatted in the dirt and pulled turnips. She takes medicine for stomach ailments and arthritis, and the work tires her. She would let the turnips dry in the sun until afternoon, then feed them to the pigs beneath

Shan's bedroom.

The grandfather grabbed a large bale of corn stalks to use as bedding for the pigs and loaded it onto his back. His arthritis sometimes keeps him from sleeping, but he said the corn was not heavy. In a lower field, a child's voice echoed against the hillsides. It was

Shan's cousin, Yang Qinlin, 4. Her own father works several hours away, and she goes months without seeing him.

She was singing a melancholy poem about missing home that is memorized by schoolchildren across China:

Looking up, I find the moon bright;

Bowing down, in homesickness I'm drowned.

An Ailing Father

On the worst nights, Yang Heqing is awakened by the cold. His bunkroom is in a warehouse district in southern Beijing that is home to tens of thousands of migrants.

There is no heat for the subfreezing temperatures, and the bunks are planks of plywood attached to metal scaffolding.

The room, provided by the construction company, is like a map of poverty in China's rural interior. Mr. Yang and three others from around his village sleep on two rows of bunks. Farmers from central Sichuan Province are in a different section. Apple farmers from dusty Shaanxi Province sleep across the room beside a few men from destitute areas in Hubei Province.

There are 40 men in a room 30 feet long.

Asked how many of them have left wives and children at home, one man yelled, "All of us." Asked how much they are getting paid for working 12 hours a day, seven days a week for almost a year, they give an embarrassed answer.

"We don't know," another man admitted.

Mr. Yang, like the others, came to Beijing last March. He and his three friends learned from a cousin about a job working on a new government building. No firm promises were made on pay. Some men were told they could earn $500 or more for the year, nearly double the average income in the countryside. Others were told that workers from different provinces would be paid different wages.

No one knows. The crew bosses will pay them when the job is done in January. Until then, the company provides daily rice or noodles, and workers get $12 a month in spending money if they work at least 25 days. Mr. Yang said he had missed many workdays because of illness. He often gets only $6 in monthly spending money as a penalty.

"Sometimes I can feel the pain while I work," he said. "My chest hurts, and I have no energy."

Mr. Yang first became sick in 2000 after five months working for an oil company in the far western region of Xinjiang. He earned nearly $600, a bounty, but he would spend all of it on medicine and visits to doctors. The diagnosis was pneumonia and inflammation of his prostate. At a city hospital, a doctor recommended $1,200 in treatment, a price he could not pay. Mr. Yang returned home, and his wife feared he might have cancer.

"He lost hope," Ms. Ran said. "He said, 'If I die, I don't care.' I said, 'You can't leave behind your parents and your daughter.' "

Weakened, Mr. Yang stayed home for four years, and his wife left for work, alone, in

May 2000. His father said he then became frustrated that his wife, not himself, was supporting the family. His daughter knew something was wrong.

"I always saw him buying medicine," Shan said. Her parents "don't know that I know," she added. "I'm afraid his sickness will become worse and worse."

In March, Mr. Yang felt he had to find work. He owed relatives nearly $300 for medical bills, and he could not make money at home. Sitting in his bunk in early December, he recalled the rush of excitement he felt arriving in Beijing to play some small role in building the country's booming capital.

His friend, Yang Xianglin, leaned over from the other bunk. He is a first-time migrant worker. Like many villagers, he thought working in Beijing would be exciting, even liberating. Now he wants to finish his job, get paid and never come back.

"It's not what we imagined," he said. "Migrant work is too hard. Even if the bosses are crooked, we have to obey them. I can't stand this. This isn't freedom."

Yang Heqing agreed, more from exhaustion than outrage. He had missed so much work that he finally borrowed money from his crew boss and visited a city hospital on Dec. 10.

A doctor examined his prostate and suggested tests. The cost was $250; the boss had lent him $12.

Mr. Yang walked from the hospital to a nearby pharmacy and bought over-the-counter anti-inflammation pills. He said he was tempted to quit, take whatever pay the boss will give him and see the doctor again. But he also knows that he might not even get paid enough to return home.

Asked about his plans for his health and his family, he could only imagine as far as

January, when his job will be done.

"My hope is for a few thousand yuan at the end of the year," he said. That is a few hundred dollars.

A Factory Mother

The outdoor market in Baoding is a patch of dirt where farmers have laid out mushrooms, tofu, cabbage and carrots. Cuts of meat are arranged on a flatbed, but Ran Heping cannot afford those. She and three relatives have just finished a 12-hour night shift at their factory and are making a weekly grocery run.

A handsome vendor haggles with Ms. Ran over the price of a head of cabbage. He is flirting and offers her a ride home. She laughs and walks away. She later says distance has destroyed the marriages of several workers at the factory.

Her factory in Baoding, about 90 minutes south of Beijing by train, makes metal balls for lawn games, to be exported to Europe and America, and smaller balls that Chinese manipulate with their hands as a form of traditional therapy.

It is dirty, difficult work, but the factory is a popular destination for migrants from

Shuanghu because of word-of-mouth referrals. More than half the 70 employees are from around the village. The job is piecework, so workers get paid for each ball. During peak

months, a worker casting metal or polishing can make more than $100. Usually, though, workers make less than $50.

Ms. Ran came here in 2000 when she left the village to support the family. Leaving her daughter worried Ms. Ran, but Shan was starting school and tuition was due. Ms. Ran also knew that her husband's illness gave her little choice.

"I knew we couldn't survive like this," she said. "I told Shan, 'I will go to work, and you be a good girl at home' "

She returned home nearly two years later. She brought almost $1,000, which went for medical bills, clothes, food, school fees, fertilizer and other farming costs. "When the money was gone, we needed more," she said. "I decided to go out again."

This time it was a shorter trip, from July 2002 until February 2003. She brought home only $210 after the factory deducted $72 for leaving without working a full year. She was furious and filed a complaint with the local labor bureau. Nothing happened.

The Yangs were together in the village for a year. But medical and school bills forced them apart again. When Mr. Yang left for Beijing last March, his wife left for a plastics factory. She later quit and tried to join her husband in Beijing.

"We are a family," her husband told her. "When we can, we should be together."

They were together for less than 10 days. Ms. Ran worked at a pastry factory but quit because the pay was so bad. She also said the cost of renting a room and living together in expensive Beijing would have erased the couple's savings.

She returned to Baoding and the metal ball factory in September. She is an inspector, an easier job that pays up to $40 a month. She is not lonely because several cousins work at the factory. They talk about their children or visit a local park together. There are days when she says being away in a big city can be exciting.

"There are no department stores where we are from," she said.

In November, she bought a bottle of shampoo for her long black hair. It was first time in her life she had ever bought shampoo. It cost $1.50.

These lighter moments are leavened by the dark. On the telephone, she pleads with her husband to see a doctor. "I said, 'When you get paid, spend all your wages to get better.' I said I would send my money home to take care of the family."

"But he doesn't really want treatment because it will cost so much," she said.

The grandparents called in December to ask for another $25 for Shan's tuition next year.

Mrs. Ran wants to visit her daughter in February at New Year's. But her bosses insist she

must work until July or again lose pay. She is angry but has decided she must stay. Her daughter does not know yet.

"I just hope that Heqing will recover and we can work together to put Yang Shan at least through high school," Ms. Ran said, when asked what she wanted for her future. "If his health doesn't improve, I'm worried we'll only be able to send her to middle school."

"It's a hard life," she added, "but we have no other choice."

An Unknown Future

Shan's grandparents say she almost never cries. She is happy playing with her friends and her cousins. Her parents both called on her birthday in July. She said it had made her happy.

In early December, she sat outside and practiced writing. The letters she had sent her parents months earlier never reached them; she did not have a reliable addresses.

Now, she started writing in a notebook.

"I want a ticket, a boat ticket and a bus ticket," she scribbled for a visiting photographer.

Where does she want to go?

"To see my parents," she answered. "I want to see my mom and dad. I think about them all the time."

For the moment, her earlier, darker image of their life had lifted. She wanted to join them.

She wanted to be a migrant worker.

"I think their life is very good," the little girl answered.

"Their life is smooth."