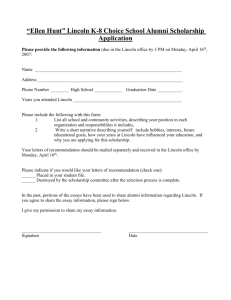

Lincoln`s Humility - Character Council of Cincinnati

Profiles in Character

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES

For HUMILITY vs Pride

Faith Committee, Character Council of Greater Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky

Humility is acknowledging that achievement results from the investment of others in my life.

LINCOLN’S HUMILITY

Compiled and Written by Steve Withrow

Introduction

One of the greatest expressions of humility in the history of our nation is to be seen in the life of Abraham Lincoln. His life exalts this virtue as few in history have exalted it. As we examine his life, we see the potential of humility, and begin to understand why this character quality is so precious to God.

Lincoln’s meekness had an infinite number of expressions, and with it an infinite number of impressions, as the sunlight of his humility enabled others to stretch and grow and believe. The purpose of this paper is to reveal how humility was tangibly expressed in the crucible of Lincoln’s life. By any measure

Lincoln was an extraordinary man. The competing interests of his day would have torn a lesser leader apart, and with him the nation. There were many giant sized egos in Washington, and throughout the country, and each of them had a cause or an agenda. Lincoln conquered them as much as is humanly possible, by his simple, direct, and thoughtful approach.

Pulling rank was always a last resort, even as Commander-in

Chief. He prevailed humbly and is a model for us to follow.

My hope is that by focusing on President Lincoln we will learn the ways of humility, and discover new ways to incorporate the many aspects of this grand virtue into our own lives as an expression of love and service to the Lord.

Since the focus of this paper is limited to those episodes in Lincoln’s life that express the virtue of humility, no attempt has been made at a comprehensive biography. This paper is simply a collection of anecdotes, with just enough commentary to keep the discussion focused.

1.

Lincoln’s humility was expressed through hard work.

He was not too proud to get his hands dirty. The man who would become our President began his work career in childhood. At the age of 8 his father hired him out to neighboring farmers to bring in extra money that helped keep the family financially afloat.

Humility is recognizing and acknowledging my total dependence upon the Lord, and seeking His will for every decision.

2

He worked a number of jobs. He labored as a farm worker, rail splitter, carpenter, riverboat man on ferries and flat boats, general store clerk, Company Captain during the Black Hawk War, merchant, postmaster, blacksmith, surveyor, self-trained lawyer, and politician.

2. Lincoln’s humility was expressed through his ability to assess and correct personal weaknesses.

Honest self-assessment is a difficult assignment, but Lincoln saw himself objectively.

This neither filled him with pride or despair. When he saw a weakness that was correctable he sought to correct it. He was disadvantaged by a lack of formal education; he had only one year. Yet he elevated himself through self-teaching to become one of our most literate and eloquent Presidents. After his single term in Congress in 1849 he worked his way through most of Euclid’s books on geometry. He taught himself law, and he memorized large portions of books.

3. Lincoln’s humility was expressed through his correctability.

When Lincoln was wrong he would allow himself to be corrected, even if the corrector was arrogant or self-serving.

An oft-quoted story is told of an incident between Lincoln and his Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton.

Lincoln, under intense pressure from a committee of Western men headed by Illinois Congressman Owen

Lovejoy, issued an important order to redeploy some troops. The notion seemed sound enough, but when

Lovejoy went to Stanton’s office to communicate the order, Stanton flatly refused.

“Did Lincoln give you an order of that kind?” asked Stanton.

“Yes he did.”

Then Lincoln is a damn fool for ever signing that order.”

Lovejoy, in amazement responded, “Do you mean the President is a damned fool?”

“Yes sir,” Stanton said, “if he gave you such an order as that.”

Lovejoy returned to the Executive Mansion (now called the White House) and rehearsed everything to

Lincoln.

“Did Stanton say I was a damned fool?” asked Lincoln when Lovejoy had finished.

“He did, sir; and repeated it.”

Lincoln’s response is so revealing of his humility. Here was a congressman from his own state standing before him, the very congressman who had obtained his allegiance and the resulting Presidential order a short time before, and now his authority was being openly challenged. Without concern for saving face

Lincoln replied, “If Stanton said I’m a damn fool, then I must be one. He is nearly always right in military matters. I’ll step over and find out what his reasoning is.”

Stanton, with his superior expertise convinced Lincoln to rescind the order, and in the process probably saved many lives.

4. Lincoln’s humility was expressed through his acts of mercy and sensitivity.

Great men often have little patience for the mundane concerns of others. Lincoln however never saw himself as too big to attend to smaller concerns that were important to others around him as this story

Lincoln with his son, Tad

3 illustrates. There were many pets at the Lincoln White House (Executive Mansion). Among them were cats, goats, ponies, a dog, and a turkey. The story of the turkey is interesting. One Christmas, the

Lincoln’s were given a live turkey to be killed for their Christmas dinner. His son Tad cried, and implored his father to write out a Presidential pardon to spare the turkey’s life. Lincoln agreed, more out of compassion for his son than the turkey, and the bird became the newest addition to the Lincoln menagerie.

5.

Lincoln’s humility was expressed through his exercise of principled flexibility.

This very quality drove even some of his supporters to distraction. He was often asked, “What is your policy?”

Lincoln’s general response was, “My policy is to have no policy.”

How can you be the President and not have a policy on crucial issues? One key to understanding Lincoln is to realize that while he had a strong sense of direction he was not hard fast in his approach. He was humble enough to realize he did not have all the answers, and that input from others was valuable, and that his goal could still be reached through constructive compromise.

Lincoln explained this tendency by drawing from his riverboat days, and explained it with a boatman’s metaphor. When you get on the Mississippi you don’t simply say, “I’m headed south.” If you do, within a short time you’ll run into a Cyprus tree or the riverbank, or a sandbar. So you zig and zag back and forth. You know where you are going, but you also know that it will not be a straight line.

6. Lincoln’s humility was expressed through his willingness to eschew favoritism.

One of pride’s favorite bastions is to surround itself exclusively with those who agree with its point of view.

That Lincoln reached out to those who strongly disagreed with him, and allowed them equal human footing is another reflection of his humility. Lincoln was a frequent visitor to the wounded soldiers throughout the city of Washington, and they were everywhere. The wounded were housed in churches, fire stations, hotels, warehouses, lodges, the Patent Office, Congress, and even Georgetown College. On

Independence Day in 1862, some church bells could not be rung because of the wounded that lay beneath the bells. And amputees were everywhere. According to Federal records, 3 out of 4 operations throughout the war were amputations.

Lincoln was no infrequent visitor to the hospitals, and Dr. Jerome Walker recorded one visit he made with the President through the hospital at City Point that demonstrates his lack of favoritism.

“Finally, after visiting the wards occupied by our invalid and convalescing soldiers,” said Dr. Walker,

“we came to three wards occupied by sick and wounded Southern prisoners. With a feeling of patriotic duty, I said: “Mr. President, you won’t want to go in there; they are only rebels.’ I will never forget how he stopped and gently laid his large hand upon my shoulder and quietly answered, ‘You mean

Confederates!’ And I have meant Confederates ever since.

“There was nothing left for me to do after the President’s remark but to go through these three wards and

I could not see but that he was just as kind, his hand-shakings just as hearty, his interest just as real for the welfare of the men, as when he was among our own soldiers.”

7.

Lincoln’s humility was expressed through his great sense of humor.

Often it was selfeffacing, and intimates said his humor was what often buoyed them throughout the dark days of the war.

One such example jabs at his physical appearance. Lincoln knew he was far from an attractive man, and often told this story about how he obtained his expensive pocketknife. Whether the story is true or not we do not know, we only know that he told it often.

4

One day a homely stranger approached Lincoln and handed him a pocketknife.

“Excuse me, sir, but I have something that belongs to you.”

“How is that?” Lincoln asked.

“This knife,” said the stranger, “was once give to me with the injunction that I was to keep it until I found a man homelier than myself. I have carried this knife for years, but let me say that you are fairly entitled to the property with the same injunction.”

8.

Lincoln’s humility was expressed through his acceptance of ridicule, disrespect, and abuse.

In the early days of the war Lincoln had great difficulty with generals who would not fight.

General George McClelland could have won the war early on if he had just pursued Lee’s forces hard, but he squandered opportunities, all the while fancying himself as a young Napoleon. Lincoln even promoted

McClelland to the rank of General-in-Chief in the hopes of motivating him, to no avail.

One evening, Lincoln traveled, with two of his staff members, to visit McClellan and to encourage him to prosecute the war. They arrived to find that McClellan was attending a wedding. The President and his aides sat down to wait. An hour later McClellan arrived, and without paying any attention to the

President he ascended the stairs to his chambers not to return. Half an hour later Lincoln sent a servant to remind the General that they were waiting to see him. The servant returned to report that the General had gone to bed.

Lincoln's aides were wroth, but the President, silent, merely arose to return home. He explained to them,

"This is no time to be making points of etiquette and personal dignity. I would hold McClellan's horse if he will only bring us success."

9. Lincoln's humility was seen through his willingness to subdue the expression of unprofitable emotions.

Despite the voltage of the times, Lincoln resisted the seduction to induce change by imposing his will through temper. Lincoln's self-control was a thermostat that would cool fiery passions just enough to enable level heads to prevail. Over the long run, this approach won him friends and allies. They knew he would not excoriate them to gratify his wounded pride. To be sure, some saw this as weakness of resolve. But those who knew him best knew it to be an expression of inner strength.

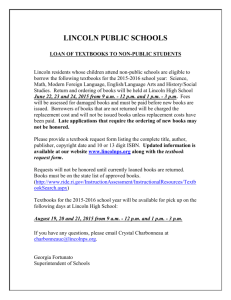

Lincoln encouraged his staff to harness their emotions as well. On one occasion, Edwin Stanton,

Lincoln’s Secretary of War, was boiling over an army officer who had accused him of favoritism.

Stanton grumbled to Lincoln, “I would like to tell him what I think of him!”

“Why don’t you? Write it all down – do.” Lincoln replied.

Thus encouraged by the President, Stanton wrote an acid letter and returned.

Lincoln listened to Stanton’s brimstone in its entirety before he responded. “All right Capital. And now, Stanton, what are you going to do with it?”

“Do with it?” Stanton asked. “Why, send it, of course.”

Edwin Stanton

Secretary of War

“I wouldn’t. Just throw it in the basket or in the stove.”

“But, it took me two days to write,” Stanton protested.

5

“Yes, yes,” Lincoln replied, “and it did you ever so much good. It’s a good letter and you feel better now.

That is all that is necessary. Just throw it in the basket.” Stanton capitulated, and into the basket it went.

10.

Lincoln’s humility was expressed in his willingness to take suggestions to heart.

Most people don’t know it, but prior to his election as President,

Lincoln had always been clean-shaven. But that all changed in response to an 11 year old girl’s suggestion that he grow a beard.

It was during the height of the presidential campaign of 1860 that young Grace Bedell from upstate New York first saw a photograph of

Abraham Lincoln. Her father had brought it home from the local fair.

To her mind, something was missing from her hero, and as she pondered she came to the conclusion that what was missing was a beard. So she wrote the candidate a letter, dated October 15 th , 1860.

Hon A B Lincoln…

Dear Sir,

My father has just come home from the fair and brought home your picture and Mr. Hamlin’s. I am a little girl only 11 years old, but want you should be President of the United States very much so I hope you wont think me very bold to write to such a great man as you are. Have you any little girls about as large as I am? If so give them my love and tell her to write to me if you cannot answer this letter. I have got 4 brothers and part of them will vote for you any way and if you let your whiskers grow I will try and get the rest of them to vote for you. You would look a great deal better for your face is so thin. All the ladies like whiskers and they would tease their husband’s to vote for you and then you would be President. My father is going to vote for you and if I was a man I would vote for you to, but I will try to get every one to vote for you that I can.

I think that rail fence around your picture makes it look very pretty. I have got a little baby sister; she is nine weeks old and is just as cunning as can be. When you direct your letter direct to Grace Bedell Westfield Chautauque County New York.

I must not write any more answer this letter right off Good bye

Grace Bedell

Lincoln did not put the little lady off. He replied right away in a letter dated October 19 th .

Private

Miss Grace Bedell

My dear little Miss

Your very agreeable letter of the 15 th is received – I regret the necessity of saying I have no daughters – I have three sons – one seventeen, one nine, and one seven years of age – They, with their mother, constitute my whole family – As to the whiskers, having never worn any, do you not think people would call it a piece of silly affection if I were to begin it now?

Your very sincere well wisher,

A. Lincoln

6

After the election, on February 11 th , 1861, the President Elect left his home in Springfield, Illinois bound for Washington, fully bearded. Five days later on the 16 th, the train stopped at the Westfield railway station in New York. Lincoln stepped out to address a cheering crowd. After expressing his gratitude for their support he took a piece of paper from his packet and announced, “I have a little correspondence here. A little lady has suggested to me to grow a beard and whiskers, Can I see her?” Within moments

Grace was in Lincoln’s arms. He lifted her high, kissed her, and whispered in her ear, “I grew this only for you. How do I look?” Grace was speechless with elation.

11.

Lincoln’s humility was expressed through his soft heart that forgave enemies and wept with the hurting.

His humility is a reflection of the knowledge he had of the power of temptation, the weakness of the will, and the blindness of the human perceptions. If you remember, in his

2 nd inaugural address he humbly said, “With firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish…” Lincoln had himself struggled throughout the war to bring meaning to the conflict.

The fact that some had not yet seen the right did not mean for Lincoln that they were irrecoverable. They could be restored and forgiven if their hearts were in the right place. Robert Ingersoll, that famed skeptic, recounts in his biography of Lincoln:

One day a woman, accompanied by a Senator, called on the President. The woman was the wife of one of Mosby’s men. Her husband had been captured, tried and condemned to be shot. She came to ask for the pardon of her husband. The President heard her story and then asked what kind of man her husband was. “Is he intemperate, does he abuse the children and beat you?”

“No, no,” said the wife, “he is a good man, a good husband, he loves me and he loves the children, and we cannot live without him. The only trouble is that he is a fool about politics – I live in the North, born there, and if I get him home, he will do no more fighting for the South.”

“Well,” said Mr. Lincoln, after examining the papers, “I will pardon your husband and turn him over to you for safe keeping.” The poor woman, overcome with joy, sobbed as though her heart would break.

“My dear woman,” said Lincoln, “if I had known how badly it was going to make you feel, I never would have pardoned him.” “You do not understand me,” she cried between her sobs.

“You do not understand me.” “Yes, yes, I do,” answered the President, “and if you do not go away at once I shall be crying with you.”

Lincoln was able to forego any spirit of prideful vindictiveness with even the most hated of opponents.

On April 2 nd , 1865, twelve days before the assassination, Richmond fell. Jefferson Davis and the

Confederate government had already evacuated, but he had left his wife and family behind. Two days later, Lincoln arrived with his son, Tad, to tour the city. He made an unannounced visit to the Davis home. Mrs. Davis came to the door holding their baby in her arms, and was understandably shocked to see Lincoln at her doorway. Lincoln gathered the baby into his arms and the child proceeded to deliver a big wet smack of a kiss on his face. He handed the child back, and said to Mrs. Davis, “Tell your husband that for the sake of that kiss, I forgive him (everything).”

12.

Lincoln’s humility was expressed through his solicitation of criticism and honest opinion.

Lincoln sought out objective criticism from those he knew would render it. He did not place value in the affirmations of “yes men.” He sought insight from those who had been some of his strongest critics, and a prime example is to be found at his 2 nd inaugural. While the Gettysburg address is

Lincoln’s most famous speech, his 2 nd inaugural address is widely regarded as his most eloquent. (A copy has been included as an appendix, and I would encourage you to read it.) Few speeches have achieved so much with such economy. It was poetic in cadence, clear in morality, honest in its assignment of guilt,

7 conciliatory in tone, hopeful in outlook, and humble before the almighty and men. It was delivered in a context where victory seemed imminent (Appomattox was just 6 weeks later), security was tight (rumors of a Confederate plot abounded & John Wilkes Booth was present), and his popularity was beginning to soar. Rain-drenched thousands braved the elements and mud to hear him speak.

Lincoln avoided all temptation to crow. He felt great responsibility to hit his marks, and lay the groundwork for reconstruction and reconciliation, and in the midst of such a task, he was unsure whether he had succeeded. That evening, at a reception in the Executive Mansion, Lincoln sought out famed abolitionist and publisher, Frederick Douglass. Douglass was a black American who had vacillated in his assessment of Lincoln over the years, and was just the man Lincoln could trust for an honest opinion. “I saw you in the crowd today, listening to my inaugural address,” Lincoln said. “How did you like it?”

“I must not detain you with my poor opinions,” Douglass replied.

Lincoln pressed on. “There is no man in the country whose opinion I value more than yours. I want to know what you think of it.”

“Mr. Lincoln,” Douglass replied, “that was a sacred effort.”

13. Lincoln’s humility was expressed through his recognition of God’s chastisements.

On multiple occasions he acknowledged the war as part of God’s judgment upon the nation. The 2 nd inaugural address is one of them, and has been included as an appendix. Another is his

“Proclamation of a Day of Prayer and Fasting,”

which was issued on August 12, 1861, near the beginning of the Civil

War. Lincoln openly called upon the nation to humble itself before God, and repent so as to place in abeyance His just punishments. His humility before God in full view of the nation is astounding.

Whereas a joint Committee of both Houses of Congress has waited on the President of the

United States, and requested him to “recommend a day of public humiliation , prayer and fasting, to be observed by the people of the United States with religious solemnities, and the offering of fervent supplications to Almighty God for the safety and welfare of these States, His blessings on their arms, and a speedy restoration of peace.” –

And whereas it is fit and becoming in all people, at all times, to acknowledge and revere the

Supreme Government of God; to bow in humble submission to his chastisements; to confess and deplore their sins and transgressions in the full conviction that the fear of the

Lord is the beginning of wisdom; and to pray, with all fervency and contrition, for the pardon of their past offences, and for a blessing upon their present and prospective action:

And whereas, when our own beloved Country, once, by the blessing of God, united, prosperous and happy, is now afflicted with faction and civil war , it is peculiarly fit for us to recognize the hand of God in this terrible visitation, and in sorrowful remembrance of our own faults and crimes as a nation and as individuals, to humble ourselves before Him, and to pray for His mercy , -- to pray that we may be spared further punishment, though most justly deserved; that our arms may be blessed and made effectual for the re-establishment of law, order and peace, throughout the wide extent of our country; and that the inestimable boon of civil and religious liberty, earned under His guidance and blessing, by the labors and sufferings of our fathers, may be restored in all its original excellence: --

Therefore, I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, do appoint the last Thursday in

September Next, as a day of humiliation, prayer and fasting for all the people of the nation .

And I do earnestly recommend to all the People, and especially to all ministers and teachers of religion of all denominations, and to all heads of families, to observe and keep that day according to their several creeds and modes of worship, in all humility and with all religious solemnity, to

8 the end that the united prayer of the nation may ascend to the Throne of Grace and bring down plentiful blessings upon our Country.

In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand, and caused the Seal of the United States to be affixed, this 12 th , day of August A.D. 1861, and of the Independence of the United States of

America the 86 th .

ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

By the President:

WILLIAM H. SEWARD, Secretary of State.

14.

Lincoln’s humility was expressed through his dutiful service to his country, despite haunting premonitions of his death.

It is true that at times great men have had a clear sense of when and even how they might die. Jesus’ knew when his hour was come. The apostle Paul could discern the outcomes of his two Rome imprisonments. Peter was given some forewarning by Christ as to the character of his demise. Perhaps this is also true of Lincoln. Without question he had been visited with two strong premonitions of death. The first was in 1860 as he stood before a mirror in his Springfield home. He saw two images of himself, which he understood to represent two presidential terms. The first image was a living man. The other was a man pale from death. The 2 nd premonition occurred a week and a half prior to his assassination, and was much more specific. This 2 nd premonition haunted him with the notion that an assassin would kill him. Ward Hill Lamon, Lincoln’s law partner from Illinois, personal secretary, bodyguard, and U.S. Marshall has recounted both incidences which he and Mary Lincoln heard from the President directly, and these were recorded by Carl Sandburg in his 1939 biography of Lincoln.

I have included them both here.

But before we recite them let’s ask the question, “Why would Lincoln serve despite his unshakeable sense that his 2 nd term was doomed.” Here, I think is a window to his humility that surrendered to the hand of providence. Sandburg quoting Lamon, estimated that three things sustained Lincoln despite his sense of an untimely end. “His sense of duty to his country; his belief that ‘the inevitable’ is right; and his innate and irrepressible humor.” In short, Lincoln saw that there were things in life bigger than himself, and issues greater than his own survival. He did not run. He played out his hand, submissive to whatever the

Lord had in store. Lincoln was no fatalist. However, this sense of being submissive to the hand of providence permeates Lincoln’s rhetoric, and is part of the essence of humility.

The First Premonition

Lincoln informed Lamon that while in his chamber in Springfield in 1860, he saw a strange vision while looking in a mirror. He saw a double image of himself. One face held the glow of life and breath, the other shone ghostly pale white. Lamon stated, “It had worried him not a little… the mystery had its meaning, which was clear enough to him… the life like image betokening a safe passage through his first term as President; the ghostly one, that death would overtake him before the close of the second… With that firm conviction, which no philosophy could shake, Mr. Lincoln moved on through a maze of mighty events, calmly awaiting the inevitable hour.” (Quoted by Carl Sandburg,

Abraham Lincoln, volume 6,

Scribner’s, 1939.)

The Second Premonition

A few days before Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, Lincoln traveled to Union Army headquarters at City

Point, Virginia to meet with General Grant. His purpose was to discuss final battle plans and surrender terms, and to sketch out reunification plans for the country to be implemented at war’s end. That night he was awakened to a vision of himself laying on a raised funeral bier, a catafalque, which is the fixed base for a casket lying in state. Here is Lamon’s quotation of Lincoln’s personal account of the dream.

9

“About ten days ago, I retired very late. I had been up waiting for important dispatches from the front. I could not have been long in bed when I fell into a slumber, for I was weary. I soon began to dream.

There seemed to be a death-like stillness about me. Then I heard subdued sobs, as if a number of people were weeping. I thought I left my bed and wandered downstairs. There the silence was broken by the same pitiful sobbing, but the mourners were invisible. I went from room to room; no living person was in sight, but the same mournful sounds of distress met me as I passed along. It was light in all the rooms; every object was familiar to me; but where were all the people who were grieving as if their hearts would break? I was puzzled and alarmed. What could be the meaning of all this? Determined to find the cause of a state of things so mysterious and so shocking, I kept on until I arrived at the East Room, which I entered. There I met with a sickening surprise. Before me was a catafalque, on which rested a corpse wrapped in funeral vestments. Around it were stationed soldiers who were acting as guards; and there was a throng of people, some gazing mournfully upon the corpse, whose face was covered, others weeping pitifully. ‘Who is dead in the White House?’ I demanded of one of the soldiers. ‘The President,’ was his answer; ‘he was killed by an assassin!’ Then came a loud burst of grief from the crowd, which awoke me from my dream. I slept no more that night; and though it was only a dream, I have been strangely annoyed by it ever since.”

15.

Lincoln’s humility was expressed through his conversion and subsequent relationship to Christ.

There has been a great deal of speculation regarding Lincoln’s specific religious beliefs. This much we know. By Lincoln’s own testimony, he was not a Christian when he left for the Whitehouse in 1861. He believed in providence. He had committed vast portions of Scripture to memory, but he had no personal connection to the Vine.

God began to deal with him intensely, after his son Willie’s death in the Whitehouse on February 20 th ,

1862. Lincoln went into a period of intense mourning, and set aside every Thursday as a personal day to mourn. After a good period of time had elapsed he was visited by a friend of the family, Dr. Francis

Vinton, the Rector of Trinity Church in New York. Vinton was direct. He told Lincoln it was not right to be so perpetually morose over the death of his son. “Your son is alive in paradise with Christ,” he said,

“and you must not continue.” Lincoln sat stupefied until his mind wrapped fully around the words.

“Alive! Alive! Surely, sir, you mock me.” “No, Mr. President, it is a great doctrine of the church,”

Vinton replied. “Jesus himself said that God is not the God of the dead, but of the living.”

Lincoln leaped up and embraced Vinton, broken and sobbing. “Alive! Alive,” he said. “My boy is alive!” From that day onward a change began in his life that his wife Mary and others noticed. His religious views changed markedly. Then in 1863 when Lincoln visited Gettysburg to deliver his famous address he gave his heart to Christ. Some time after, an Illinois clergyman approached Lincoln and asked him directly, “Mr. President, do you love Jesus?” Lincoln’s reply is documented in a letter from this clergyman. “After a long pause, Mr. Lincoln solemnly replied: “When I left Springfield I asked the people to pray for me. I was not a Christian. When I buried my son, the severest trial of my life, I was not a Christian. But when I went to Gettysburg and saw the graves of thousands of our soldiers, I then and there consecrated myself to Christ. Yes, I do love Jesus.” (Source: from the Lincoln Museum across from

Ford’s Theatre in Washington. The Lincoln Memorial: Album-Immortelles in the O.H. Oldroyd Collection. P.366.

1883.) [ Dr. D. James Kennedy has written a wonderful essay entitled, “Was Abraham Lincoln a Christian?” that provides even more documentation of Lincoln’s conversion. [See www.pastornet.net.au/jmm/afam/afam0054.html]

Perhaps the culmination of Lincoln’s theological understanding is to be found in his 2 nd Inaugural address, a sermon of great humility that encapsulates Lincoln’s synthesis of the intersection of Divine providence with human responsibility.

10

Appendix: Lincoln’s 2

nd

Inaugural Address

March 4, 1865

Fellow countrymen: At this second appearing, to take and a result less fundamental and astounding. Both the oath of the presidential office, there is less occasion for an extended address than there was at the first.

Then a statement, somewhat in detail, of a course to be pursued, seemed fitting and proper. Now, at the expiration of four years, during which public declarations have been constantly called forth on every point and phase of the great contest which still absorbs the attention, and engrosses the energies of the nation, little that is new could be presented. The progress of our arms, upon which all else chiefly depends, is as well known to the public as to myself; and it is, I trust, reasonably satisfactory and encouraging to all. With high hope for the future, no prediction in regard to it is ventured.

On the occasion corresponding to this four years ago, all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil war. All dreaded it – all sought to avert it. While the inaugural address was being delivered from this place, devoted altogether to saving the Union without war, insurgent agents were in the city seeking to destroy it without war – seeking to dissolve the Union, and divide effects, by negotiation. Both parties deprecated war; but one of them would make war rather than read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully. The Almighty has his own purposes. “Woe unto the world because of offences! For it must needs be that offences come; but woe to that man by whom the offence cometh!” If we shall suppose that American Slavery is one of those offences which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through

His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and

South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offence came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a Living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope – fervently do we pray – that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let it perish. And the war came.

One eighth of the whole population

Lincoln as he appeared in April 1865.

The last portrait before his death .

were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the

Union, but localized in the Southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the

Union, even by war; while the government claimed no wealth piled up by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.”

With malice toward none; with charity for all, with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it. Neither party expected for the war, the magnitude, or the duration, which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan – to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.