The Christian Faith of Dietrich Bonhoeffer

advertisement

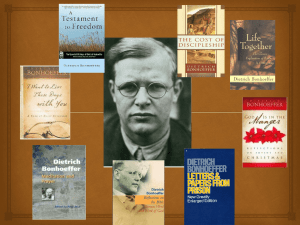

1 The Christian Faith of Dietrich Bonhoeffer Twenty-one years ago, The Kreiders, the Hildebrands, the Hintzes, the Ratzlaffs and we spent a year studying this booklet, Life Together written by Dietrich Bonhoeffer. The book was instrumental in helping our group focus on the undertaking which we had envisioned and came about in the Menno Simons Centre and the beginning of this congregation in September of 1986. This booklet was written by Bonhoeffer to provide pastors who were training at his illegal Seminary with an understanding of life together in a church community. A subtitle on the cover further explains that this booklet is a discussion of Christian fellowship. We have now completed almost twenty years of fellowship in this place and so this year is a good time to reflect our experience and compare in a small way with that of the ideals set out in this booklet. Our Anabaptist forefathers focused on the life of the Christian in this world. Menno Simons came to understand the centrality of faith based on the life and death of Christ as contained in the gospels of the New Testament. He also emphasized that this had to be actualized in the life of the Christian as a life of faith in this world. Bonhoeffer found the same centrality of the message in his short lifetime. A phrase that is helpful for us is one he wrote in a letter to his father who had taught him what he termed, an insistent realism, a “turning away from the phraseological to the real.” For him, Christianity could never be merely intellectual theory, doctrine divorced from life, or mystical emotion, but always it must be responsible, obedient action, the discipleship of Christ in every situation of concrete everyday life. Bonhoeffer was born in 1905 and grew up in a Germany that can be characterized as a European centre of culture and learning. The heritage of music and art, literature, philosophy, psychiatry, theology, and science in the early 20th Century was at the forefront of that of any country. His family was of German aristocracy and had been strongly connected to government and learning. Dietrich’s father was a leading psychiatrist and head of the psychiatric clinic in Berlin. As a side comment, his father did not agree with the theories of Freud. The religion in the family home was that of the national state religion, namely Lutheran. Church attendance was not regular, but prayer and celebration of the major religious events was a part of the family “culture”. Bonhoeffer was an excellent pianist and in his teens considered a career as a pianist. He kept an instrument in his room and took one with him to his various places of residence. He enjoyed the luxuries of regular forest and seaside vacations, read widely and extensively. At the age of sixteen, he was sure he wanted to study theology. His informal education continued when he spent three months in Rome to study the Catholic Church which according to his diary helped him to understand the “concept of the church.” Bethge, his biographer says “Bonhoeffer’s attention was soon completely absorbed by the phenomenon of the church… He based his core theological principles upon this ambiguous but concrete structure. His journey to Rome essentially helped him to articulate the theme of ‘the church.’ The motive of concreteness – of not getting lost in metaphysical speculation – was a genuine root of this approach.” 2 He finished his doctoral dissertation, The Communion of Saints at age twenty-one. This was his first publication and was a strong theological beginning of Bonhoeffer’s lifelong interest in exploring the nature and vocation of the church within society. He began to read Karl Barth and found resonance with his thinking. Bonhoeffer’s description of the church as “Christ existing as the church community” would prove to be a standard of whether churches truly reflected the spirit of Jesus Christ. He began to serve in concrete church settings, spending a year in Barcelona, serving the German churches there, a year in New York studying at New York’s Union Theological Seminary where he came in contact with Niebuhr and also a classmate Jean Lassere, a pacifist with whom he maintained a lifetime friendship. He came into contact with the black Abyssinian Baptist Church in New York. He spent a year in London, again serving the German churches there. Here he made very significant connections with the Anglican Bishop Bell. When in Berlin he either taught at the University or pastored a church, notably a church in the poorest part of Berlin where he worked specifically with youth. He served as a representative for the ecumenical councils such as the World Alliance for Promoting International Fellowship as well as the Universal Christian Council for Life and Work. Here he made a huge impact with his almost prophetic messages and challenges. In Barcelona, New York and in Berlin, he had his first experiences with poverty. He began to sensitize his congregants to those less fortunate and throughout his ministry he began to counsel the community to look on the diversity not as a problem of the common life, but as a cause for rejoicing and an opportunity to tighten community bonds. Bonhoeffer implied that the community’s strength lies in the care it takes of its weakest members. The elimination of the weak is the death of the community he said. These are words written in the face of Nazi determination to euthanize the mentally and emotionally weak and physically handicapped. He was referring not only to society but also to the church. The practical directives he gives in his book, Life Together, are all related to the manner in which a community’s diversity provides and opportunity for individuals and the community itself to grow in the love of Jesus Christ and in their love and esteem for one another, especially the most vulnerable of their brothers and sisters. The core he develops to integrate diversity into the formation of community faithful to Jesus Christ is in the promotion of mutual service that, like common worship, Scripture reading, table fellowship and private and communal prayer is necessary for the community to grow in love for one another and into the image of Christ. Within a strong family setting, Dietrich, came to study theology. That sentence implies more than it seems. Germany was renowned for its theologians and philosophers and you may well be familiar with such names as Harnack, Bultman, Barth, Nietzsche, Tillich, etc. The teaching of theology was a significant component of University training of Lutheran pastors. He was greatly influenced by the writings and teachings of Karl Barth. Although he was a serious student of theology, it was as a student of theology that he recognized that a faith in Christ demanded more than head knowledge, that faith in Christ is a powerful experience of conversion and commitment. Moreover, such conversion and commitment is an all encompassing act. It engages the Christian in a belief so profound as to reorder the Christian’s priorities and his perspective of living. This was profoundly the case in Bonhoeffer’s life. 3 The common term for the focus on the life and teachings of Christ is the word, Christology. Let me elaborate on this central focus: The Christian’s view of who Christ is, is central. Christ is God’s Son, one of the Trinity, comprising of God, Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit. Jesus Christ is the image of the invisible God, the first born of all creation: “for him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions, or principalities or authorities – all things were created through him and for him.” ( Col. 1:15-17) As a result we accept that the whole of creation had Christ as its prime force and purpose. It was intended from the very beginning by the triune God for the purpose of creating a world into which man could be placed and eventually God would enter through Jesus Christ in order to communicate with man. Not until our recent study of Bonhoeffer’s theology has this concept, this direct link of creation with the purpose of Christ’s entry into the world, become clear and powerful for me. We see the whole of creation including mankind who has been given reason and understanding as divinely ordered and created by God, through Christ. The Christian accepts God’s revelation of this knowledge to us. We, therefore, as Christians think outside the box of human understandings which seeks to provide formulas and schemes as to how the world came about. We accept as an a priori fact that the universe was created by God, through Christ. We accept this as a revelation. The writer to the Hebrews is able to say “in these last days (the Father) has spoken To us in his Son…. through whom also he made the world. (Heb.1:2) The purpose for which the world was created and why the world was created is central to the understanding of Christology. Again, “He was in the world, and the world was made by him, and the world knew him not. He came unto his own, and his own received him not,” found in John 1:10 Because the triune God created all things, He is not a created being – he is the external uncreated Creator. For me this understanding satisfies any questions in respect to the creation vs. evolution debate. It is one thing to think of the world as being separate from Christ as creator and then to argue as to the legitimacy of the gospel of his coming into the world. It is a whole different concept to accept that for Him and through Christ the world was created. That it is sustained by and through Christ so that he could come into the world in order to provide and entry 4 or access for man to God. We further accept that God in Christ is the beginning and end of all true wisdom and knowledge and that he is the true source of truth. That the Christian life as taught by Christ provides us with the best possible “way” and the best possible “Life”. That the Christian destiny goes above and beyond life here on earth. That in our living we govern our priorities on that basis, that we are part of God’s purpose that goes beyond the grave. That the cross and resurrection are central to our redemption. All other human attempts of attaining spiritual goodness or wholeness are only partially successful in the ultimate sense, particularly if they are judged by human standards. Christ is also characterized as the sustainer of all things. As the world’s creator the Son is not only “before all things but in him all things hold together”. The one who created the world is also the one who sustains it. It is the Son who “upholds all things through the word of his power”. The entire created universe is contingent upon him at every point and in every way. The cosmos created by God is not simple. It is multifaceted. It has physical, spiritual, and moral dimensions to it. The creation, not the human creatures, gives form to matter, animation to dust, order to chaos. One writer puts it this way “The root of enacted law is the moral law. The root of the moral law is the design of the created order The root of the created order is the Creator. Conversely, enacted law severed from moral laws is chaos Ethics, severed from moral law, is perversion Creation severed from the Creator, is an idol.” 5 When Bonhoeffer had the experience of faith, he saw life in a new way. For the next twenty or so years of his life, Bonhoeffer lived the life of a follower of Christ. This led to his death as a martyr in Germany under the regime of Hitler. We have many of his writings which set out his strong Christology and reflect the concepts of living the Christian faith as in his Ethics book and the depth of commitment to a life of following Christ as set out in The Cost of Discipleship. Bonhoeffer had many injunctions for the church. One of his most important contributions during the Nazi period was to break away from the Lutheran church controlled by the National Socialists under Hitler and form the Confessing Church. He then established a Seminary to train the pastors of these confessing churches, first in Zingst on the Baltic coast and then in Finkenwalde. We visited both of these places on our recent trip. What he hoped to achieve was a church of faith and practice. Here is an excerpt form his Ethics book reflecting on the failures of the church: The church confesses that she has not proclaimed often and clearly enough her message of the one God who has revealed Himself for all times in Jesus Christ and who suffers no other gods beside himself. She confesses her timidity, her evasiveness, and her dangerous concessions. She has often been untrue to her office of guardianship and to her office of comfort. And through this she has often denied to the outcast and to the despised the compassion which she owes to them. She was silent when she should have cried out because the blood of the innocent was crying out loud to heaven. She has not resisted to the uttermost the apostasy of faith, and has brought upon herself the guilt of the godlessness of the masses. Some who seek to escape from taking a stand publicly find a place of refuge in a private virtuousness. Such a man does not commit any sins pursuant to the ten commandments, and we would not pour scorn on such a man, but it is not enough. He was of course referring to the Lutheran churches failure to protest the treatment of Jews, gypsies, the physically and mentally challenged and homosexuals and others not acceptable under the Aryan race purity principle. In order to better understand Bonhoeffer’s struggle under the National Socialist Party of Hitler, we have to understand the place of the Lutheran church in Germany. It is a state church supported by a tax system and governed by a church administrative hierarchy. It was relatively easy for Hitler firstly to make deceptive statements that he intended the church to have a significant “Christian” role in the new Germany which held the churches in thrall. Secondly, the Nazis could control the appointments of the Bishop and administrative seats and with threats and coercion forced the church to accept his projects and purposes. Bonhoeffer challenged the Lutheran church in its failure to respond to the direction of the church and its fear and lack of moral leadership. Few if any sermons 6 from Lutheran pastors spoke with critical perception of the lack of moral leadership on the part of the church. Bonhoeffer refers to the approach of the church and that of society in general as: The astonishing experience of the deification of the irrational, That surely it could be countered as follows, Of blood and instinct, of the beast of prey in man could be countered with the appeal to reason; Arbitrary action could be countered with the written law, Barbarity with the appeal to culture and humanity The violent maltreatment of persons with the appeal to freedom Tolerance and the rights of man; The subordination of science; Art and the rest to political purposes with the appeal to the autonomy of the various fields of human activity. Reason, culture, humanity, tolerance, autonomy and self determination, all concepts that had until now served as battle slogans against the church, against Christianity, against Jesus Christ himself, had now suddenly and surprisingly become the domain of the church in speaking to the atrocities of the Nazi regime. These concepts no longer had a home in society at large and sought refuge in the church. Bonhoeffer goes on to elaborate that there is only power and strength in Christ, not only in the church but in the concepts of humanity, reason, justice, and culture. That Bonhoeffer became a radical disciple of Christ is the key to his life. He says of his conversion “something happened” that transformed his life from what it was before. What it had been was not Christian. He says of this turning point in his life: I discovered the Bible. I had often preached about it - but I had not yet become a Christian. The life of a servant of Jesus Chris must belong to the church, and step by step it became clearer to me how far that must go The Cost of Discipleship is a booking which Bonhoeffer, using Jesus’ own words and the exhortations of the Apostle Paul, confronts readers with the uncushioned challenges to all their distortions of what it means to be follower of Jesus Christ. Bonhoeffer probes the seemingly “impossible demands” of Jesus’ sermon on the Mount against the economic materialism, patriotic militarism, and ruthless racism to which Christians and their churches had succumbed in Nazi Germany. He went so far as to state that cheap grace is the mortal enemy of our church. Our struggle today is for costly grace. 7 He preached on the basis of John 8: 31-32 “If you continue in my word, you are truly my disciples, and you will know the truth and the truth will make you free.” For him freedom was not a revolutionary slogan. Truth was not to be found in the mastering of church-sanctioned truths in catechisms, creedal formulae and dogmatic treatises. Truth and freedom were always connected in Bonhoeffer’s preaching and always based on the truth in Christ. He challenged the carefully worded responses of the state church so as not give offence to the Nazi government. People became totally submissive because of the ruthless and swift punishment and as a result there was a complete loss of freedom of speech. We have echoes of such denial of freedom of speech even in our time on moral and political issues in that it is not politically correct to hold a position which may be different then what popular opinion sanctions. To speak of freedom as arising from truth is difficult. Bonhoeffer concluded that everyone wants to be free and everyone strives to be free. But does the notion of truth create a problem? He said yes. He argued that people realize the “truth” may seem cold uncompromising, and disturbing. It raises our anxiety before God. God may shine the light of truth on us and reveal our dishonesty and lack of freedom. Truth is a power that stands over us and at any moment can undo us. No one can deny that social lies, political lies and self –serving lies exercise a domineering power over people. Sooner or later, this duplicity is recognized. Bonhoeffer’s climactic statement in this regard was that not Adolf Hitler, but the people who love, because they are freed through the truth of God are the most revolutionary people on earth. They are the ones who upset all values; they are explosives in human society. This disturbance of peace, which comes to the world through these people, provokes the world’s hatred. He recognized also this freedom and truth spoken clearly would lead to suffering. As mentioned earlier, during his year in Barcelona, he ministered to the poor and was offended by the attitude of the church towards the poor. At church gatherings for discussions on forms of worship and even new church music in the Hitler era he said: “Only those who cry out for the Jews may sing Gregorian chants.” The liberating effect of Bonhoeffer’s Christ centered freedom was clearly evident in his life experiences. He identified strongly with the impoverished blacks in Harlem during his stay at Union Theological Seminary in 1930-31. This showed him how poverty could be tied to racism. He became attached to the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem. He particularly admired the deep liberating spirituality of their hymns at worship. He predicted even then that white America would have to acknowledge its guilt and was astonished at the silence of the church on this matter. He took many of the spirituals back with him to Germany. He believed in a Spirit-inspired interpretation of the Scriptures In one of his early essays he writes, “Does one read the Scriptures in a purely scientific mode or in a spirit of prayer and faith with the mind opened to what God, and not skilled scientific exegetes, may be saying? The Christian religion, he says, stands or falls by belief in the divine revelation that 8 became historically real, tangible and visible – that is, to those who have eyes to see and ears to hear.” The Christian religion, in its very essence contains the question that we ask ourselves today about the relationship between history and spirit, scripture and revelation, man’s word and God’s. He had become disgruntled with the textual criticisms of his mentors. He stated that textual criticisms left only “rubble and fragments” Bonhoeffer did not repudiate the historical-critical method – in fact he insisted that it was still necessary. He thought however, that the scientific approach had to give way to the pneumatological, which inevitably became “prayer… and supplication to the Holy Spirit”, which alone as it pleases gives, it the hearing and understanding “without which the most highly intellectual exegesis is nothing” In respect to the Church, Bonhoeffer’s insight that God’s Spirit makes possible the birth, growth, and enhancement of individuals into a church community is foundational. Every church community in Christianity claims its foundational bondedness to the Holy Spirit and it is not merely a lifeless line from a creedal litany. What that means in the practical living out of the gospel this was his major preoccupation during the crisis years. He was particularly concerned that the common bond be based on the Spirit and love rather than a superficial congeniality or an association of kindred spirits. The acts of love which the Holy Spirit brings about are the very heart of the community of spirit. Those who in the spirit organize their relationships to others, do so with a single end in mind, to fulfill God’s will by loving others. Much more on this topic can be found in his book, Life Together which he wrote during his work in the seminary. Bonhoeffer makes a direct connection between his insistence on doing what Christian faith demands and professing that faith with creedal accuracy within the church community. The fidelity to Jesus, made possible by the Holy Spirit within the church community, is much more than purity of orthodoxy. Bonhoeffer builds his argument on Paul’s exclamation of 1 Cor. 12:3: no one can say “Jesus is Lord” except by the Holy Spirit and contrastingly, not everyone who says “Lord, Lord” will enter the kingdom, but only the one who does the will of my father in heaven. For example, even the confessing church (the alternative church that Bonhoeffer began) ultimately failed because it had resisted by its confession, but had failed to confess by its resistance. The year preceding the formation of the Pacific Centre for Discipleship as well as Point Grey Fellowship (I say Point Grey Fellowship because there was a clear intention to be more community friendly rather than ethnically focused during our initial discussions), our small Bible Study group studied Bonhoeffer’s book, Living Together. It was foundational in my thinking of the kind of church fellowship we wanted to experience. Twenty years later, and especially after a thorough experience of Bonhoeffer’s thought, I resonate strongly with Bonhoeffer’s theology, especially on his teachings focusing on Christ and the work of the Holy Spirit in the church. The question we must answer is whether or not we have been able to achieve at least some of the early intentions of our fellowship. 9