Special Problems with Analytical Papers.doc

advertisement

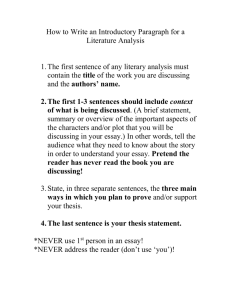

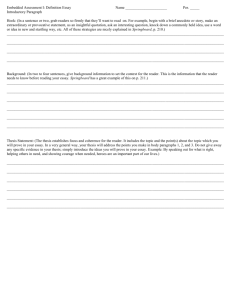

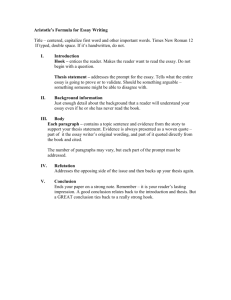

1 Special Problems with Analytical Papers The introduction: what the reader reads first and the writer writes last. Things go wrong with introductions because inexperienced writers think they introduce the writer to the subject. They don't. They introduce the reader to the subject. An introduction tells the reader what the paper is about and how the paper will be constructed. That's why you can't write it until you've finished the paper and figured out what you're saying. The sentence-by-sentence structure below may seem constrictive, but consider it (mentally, if not on paper) before you develop your own modifications. The first sentence tells the reader what the paper is about and hints at the direction the paper will take. If you're writing about a book, cite its title and its author's name in the first sentence, then relate it to your topic. For example, if you're writing about marriage customs in Pride and Prejudice, begin "In Pride and Prejudice (1819), Jane Austen discusses marriage customs among the English gentry in Georgian England." If you're writing about the influence of St. Augustine's philosophy on the political thought of 17th century Puritans, try to get both subjects into the first sentence. For example: "Seventeenth century Puritan thought resulted in many forward-looking political reforms, but its source, St. Augustine's City of God, was thirteen centuries old." (If you can't get both subjects into a single sentence, use two sentences. Just be sure the reader knows the subject of the entire paper before you go on.) If you're writing about a historical or political situation, try to tell the reader the events and the time period the paper covers in the first sentence. "One of the least- known causes of the American Revolution was the stupidity of the British Ministery in the 1760's and 1770's." "The English Revolution that began as an attempt to force Charles I to reform ended with his execution in 1649." If you're writing a comparison-contrast paper, it may take you two sentences to begin because you need to establish a context for the comparison. "Psychological states are not the provinces of psychologists alone; long before the advent of Freudian thought, poets discussed mental illness allegorically. Today, we are likely to turn to a medical or psychiatric encyclopedias for a definition of Narcissism; first-century Romans turned to Ovid's Metamorphoses." If you're writing about a single philosophical term, begin by defining it; if you're writing about a philosopher's USE of a philosophical term, tell the reader how he defined it. "The just man, in Plato's definition, was one whose spirit and appetite were governed by his intellect." 2 The second sentence of the introduction tells your reader what you have to say about the subject you introduced in the first sentence. The second sentence of your Jane Austen paper, for example, will say: "Austen assumes the reader knows that gentle status was determined by unearned wealth; her opening sentence acknowledges the importance of ‘a single man of a good fortune’ in a society that requires money but allows neither gentlemen nor ladies to work for it." The second sentence of the Augustine/Puritan paper will indicate Augustine's specific influence on Puritans: "Seventeenth century Puritans were influenced particularly by Augustine's description of the Fall in Book XIV; this description, which introduced the idea of prelapsarian predestination ( God's knowledge that Adam and Eve would fall) and formed the core of Puritan theology." (Note that the technical term is defined in parentheses. If a definition is too long to be incorporated gracefully in a parenthesis, put it in a footnote — at the bottom of the page, where the reader can see it.) The next two sentences (or three, if you need them) finish telling the reader what the paper will be about; they also describe the paper's structure. These sentences always take a long time to write, because the wording must allow you to make a bridge to the body of your paper while indicating how the body will be structured. Look at the key words below: "The plot of Pride and Prejudice reflects upon the reactions of different men and women to the specter of relative poverty or work. With wry humor, Austen presents the marriage alliances determined by social necessity, and she implicitly asks how a man or woman can attain happiness in a world that puts a price on love. By contrasting the courtship of Elizabeth Bennet and Darcy with those of the other characters in the book, Austen suggests a solution to the problems wealth thrusts upon society." The key words in the last two sentences of any introduction are structural words. "A comparison of Thoreau's definitions of ‘needs’ and ‘wants’ reveals that . . ." "The Peloponnesian war had many causes, but the three most important were . . ." (cite them in the order you'll discuss them) "While Plato talks about epistemology in The Meno, he develops his ideas in . . . . (give the names of the later dialogues, in the order in which you'll discuss them) "While a comparison of realism and deterrence reveals five basic differences between them, the feminists assert that the two groups are ideologically indistinguishable. (This sentence tells the reader you'll first compare realism and deterrence on five points, then say what the feminists say is wrong with both positions.) A few “don'ts” on introductions. Don't spin your wheels by starting with a pseudo- impressive statement filled with cliches: "Since the beginning of time, man has stood with his feet in the mud and his eyes on the stars, wondering about his fate." 3 Don't start with a lame statement. "A study of Egyptian gods reveals many interesting things." Don't start with a rhetorical question, or worse yet, a series of them. "What is Truth? What is Justice? These are questions that Plato takes up in his timeless dialogues . . . " Don't start a paper with a quotation. The readers have no idea why the quotation is there, so you will have to spend several sentences explaining what it has to do with your paper. Remember: All the introduction needs to do is tell the reader what the paper is going to say and how the material will appear. Keep it clear and simple. ________________________________ The body of the paper: report vs. analytical essay. The report says, in effect: "here are some interesting facts I learned about the following subject." There are places for reports. In business, a boss needs information she cannot collect herself, so she asks her employees to investigate situations and write up the results in an accurate, objective manner. She doesn't want opinion; she doesn't want analysis — she just wants the facts. In journalism, reporters do not analyze material for the paper's readers (unless the article is specifically introduced as a "news analysis" or "editorial"); they present the readers with an account of what happened. n the sciences, people must report the outcome of their laboratory experiments accurately and clearly. The lab report may serve as a basis for later analytical essays, but as a form unto itself, it must simply describe facts in a way a reader can understand them. An analytical essay is not a report: it analyzes the subject matter of a report and says something about it. An essay has a thesis; the material it presents is always subordinated to the point the author is trying to put across. The information presented in an essay is NEVER an end in itself. The two sentences you write on a separate sheet before you start the essay ("This paper is about . . .; my thesis is . . . .") should prevent you from writing a report when you need to write an essay. Still, in the throes of composition, it is easy to lose your way. Learn to stop and ask, Am I just saying "here is some interesting stuff I learned about my subject?" or am I saying "Here is what I think about this subject, and here's why I think so?" If you find yourself unintentionally writing a report instead of an analytical essay, the following things may have gone wrong: ) You haven't organized your notes thoughtfully enough. Go back to the note- 4 taking stage and start again, selecting points you particularly want to emphasize, and subordinating other points to the main ones. 2) You haven't taken time to figure out what your thesis is. Do it now, then go back and start again. 3) You have set up everything pretty well, but you've lost sight of your thesis in the hecticity of composition. (This happens to everybody; don’t feel badly about it.) Go back to the last place you were supporting your thesis, make sure everything is all right up to that point, then continue. __________________________________ Conclusions: please conclude something. If you state your conclusion (as opposed to your thesis) in your introduction, the conclusion you write at the end of the paper will simply repeat what you said before. The "bridge sentences" of your introduction point the reader toward the conclusion, but they do not state it. For example, the bridge sentence in the Jane Austen paper above does NOT tell the reader Austen's solution to the problem of wealth, happiness, and status. It simply says she DOES present one. The conclusion may summarize your points, but if you've made them clearly, you'll find you're writing a re-hash of your topic sentences. As the conclusion shouldn't repeat the introduction, so it shouldn't repeat the body. 5 Think of the conclusion as being the "so what?" of your paper. It refers to your thesis, it rounds things off, and (if you're clever) it repeats the wording, though not the content, of the introduction. If you write the introduction and the conclusion at the same time, linking them verbally is comparatively easy. Some don'ts on conclusions. Don't end with a rhetorical flourish. "And so we can see that Plato, the world's greatest philosopher, made the just man his hero — thus affecting the mentalities of men for ages to come." Don't end with a thud. "Jane Austen's opinion on love and marriage is typical of her generation." Don't end with an obvious statement. "And so you can see that dogs are different from cats." (This kind of statement is always a threat to the comparison-contrast paper. You must show why the contrast is significant, not that it exists.) Don't end with a paragraph that contradicts your introduction. "And so, you can see that what I said at the beginning of this paper isn't what I really thought . . ." This won't happen to you if you write the introduction last. Don't add new material in the conclusion. "The thought of the seventeenth century Puritans influenced John Milton and gave birth to his great epic, Paradise Lost. (If this is the first we've heard of Milton, don't say it — or, if you want to say it, bring up the point earlier.) Don't end with a quotation. Why should you let somebody else wrap up your paper for you? Don't end a paper without a conclusion.