dramaticmonologue.doc

advertisement

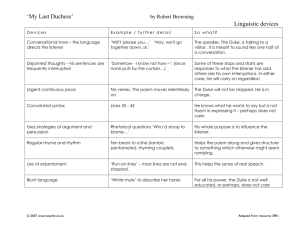

Babienko AP English – “My Last Duchess” Definitions of the dramatic monologue, a form invented and practiced principally by Robert Browning, Alfred Tennyson, Dante Rossetti, and other Victorians, have been much debated in the last several decades. Everyone agrees that to be a dramatic monologue a poem must have a speaker and an implied auditor, and that the reader often perceives a gap between what that speaker says and what he or she actually reveals. In one of the most influential, though hotly contested definitions, Robert Langbaum saw the form as a continuation of an essentially Romantic "poetry of experience" in which the reader experiences a tension between sympathy and judgment. One problem with this approach, as Glenn Everett has argued, lies in the fact that contemporary readers of Browning's poems found them vastly different from Langbaum's Wordsworthian model. Many writers on the subject have disagreed, pointing out that readers do not seem ever to sympathize with the speakers in some of Browning's major poems, such as "Porphria's Lover" or "My Last Duchess." Glenn Everett proposes that Browninesque dramatic monologue has three requirements: 1. The reader takes the part of the silent listener. 2. The speaker uses a case-making, argumentative tone. 3. We complete the dramatic scene from within, by means of inference and imagination The first distinguishing characteristic of Browning's dramatic monologues is the point of entry, which, I argue, is not through an empathetic relationship with the speaker. The experience Browning offers us is not the same as that offered by the Wordsworthian lyric, although the poets begin the same way. In both cases, the poet's subject is the psychology of the speaker, and in both cases the author explores the speaker's point of view by means of imaginative sympathy -- Einfuhlung. With the Wordsworthian lyric, the reader's job is to achieve that sympathy; with the Browningesque monologue the reader may instead take the part of the listener, and this point of view is always available within the form. Indeed, the auditor may appear to be absent (as in "Johannes Agricola"), dead ("Porphyria's Lover"), out of earshot ("Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister"), or simply inattentive ("Andrea del Sarto"). Second, whether this auditor is present does not matter so long as we find the speaker using the same kind of case-making, argumentative tone that marks "My Last Duchess" and which is the second definitive characteristic of the type. In all these instances the real listener (that is, the target of the argument) is the speaker's "second self"; and it becomes clear that in many monologues the putative auditor within the poem is less important than this Other. The arguments in "Karshish" are not really intended for Abib's eye, but for Karshish's own, as the rationalizing in "Cleon" is not intended to dissuade Protus's interest in Paulus and in Christ, but Cleon's own. The tone of the argument tells us that there is a second point of view present, and it is that point of view which we take. It is this strongly rhetorical language which distinguishes the dramatic monologue from the soliloquy, for it shows the speaker arguing with a second self. We are coaxed out of our natural sympathy with the first-person speaker by the vehemence of the arguments made; and if Abib or Lucrezia are not impressed by the arguments, we take their places within the monologues and listen as they should. As its third important distinction, the form requires that we complete the dramatic scene from within, by means of inference and imagination, and thus these texts are rules by which the reader plays an imagined drama. The clues which Browning's speakers provide to their obsessions are observable only if we imagine ourselves within the dramatic situation, with the speaker there before us. (Because Wordsworth intends to put us within the mind of the speaker, his poems remain essentially lyric.) In order to read the poems in this way, we must often sacrifice our certainty about which way to take them: do the Bishop's sons really give him cause for worry that they will substitute travertine for his antique-black and make off with his lapis lazuli, or is he paranoiac? What word did Porphyria's lover expect to hear from God? Was there any truth to the "lie" that Count Gauthier told and Gismond made him swallow? We and the listeners in these dramatic monologues can only speculate, for within the text neither they nor we can find conclusive proofs. This indeterminacy, which his first readers found so distressing, accords with Browning's own "uncertainty" about what happens in his poems: most famously his Babienko AP English – “My Last Duchess” comment to Hiram Corson that the Duke might have had his Duchess put to death--"or he might have had her shut up in a convent" (Corson viii). Since the envoy cannot know conclusively, neither can we. The distinguishing characteristic of Browning's dramatic monologues is that they make new demands of the reader, and those extra-textual demands are signaled within the text by the figure of the auditor. That listening figure and the tone which the speaker adopts in order to make his or her case are the most important new ingredients in the Browningesque dramatic monologue. Because the listener is not always physically present, most critical assessments have misunderstood its significance. In fact, the presence of the auditor determines how the reader must react to the speaker, and thus the proper questions about the poem are not those which ask about the relationship between the speaker's ideas and the poet's; instead we must ask about the speaker's effect upon his listener. From this rhetorical effect we can infer the dramatic situation, and it is the interplay among the characters in these scenes which Browning wishes us to imagine. Observing the speakers as their listeners do, we find we have to piece together scraps of information to complete a picture of the speaker, and even, sometimes, simply to figure out what is going on. Thus, in each re-reading we must relive the process of discovery which the listener experiences. Rather than a balance of sympathy and judgment, a better description of this process of discovery is engagement, then detachment: we readers must become engaged in the game of imagination which the poem asks us to play before we can attain a detached, critical view of the whole work. How do we read "My Last Duchess," one of the most representative dramatic monologues? The old "sympathy/judgment" model does not seem to work very well. Langbaum, the main proponent of this view, finds that the Duke's immense attractiveness . . . his conviction of match less superiority, his intelligence, and bland amorality, his poise, his taste for art, his manners, overwhelm the envoy, causing him apparently to suspend judgment of the duke, for he raises no demur. The reader is no less overwhelmed. We suspend moral judgment because we prefer to participate in the duke's power and freedom, in his hard core of character fiercely loyal to itself. (83) Hazard Adams points out that sympathy does not seem to be the right word for our relationship to the Duke (151-52), and Philip Drew protests that suspending our moral judgment should not require "an anaesthetizing of the moral sense for the duration of the poem" (28). Langbaum is right that the intellectual exercise of inferring the real character of the last Duchess from what the Duke says about her to the envoy and then going on to make a moral judgment about him constitutes a large part of our enjoyment of the poem, but that enjoyment is not dependent upon our entering into sympathy with the Duke. Rather, we enter into this scene on the side of the envoy, and at that level we feel the pull of the Duke's commanding rhetoric. In order to read the poem, we must create the scene in imagination, which means "losing ourselves" within it, forget ting, for the moment, our real, present surroundings in favor of active involvement in the dramatic situation. Our entry is facilitated by its most striking feature, which is the way the Duke so directly addresses us. His narrative in the center of the poem is carefully framed by the first ten lines and the last ten, in which he addresses someone as "you." Because we do not discover until after he has told his tale that this second person is in fact present in the poem, at the moment of our reading we can only assume that it is us to whom he is speaking. (It is true that we eventually discover that this "you" to whom he is speaking is an envoy from a Count, but this identification is not made until very late in the poem.) We are slightly disoriented, on a first reading, by that direct address, and we recognize that an effort is being made to suggest that we are the silent partner in a conversation; even the omission of quotation marks helps sustain the illusion that we have encountered a character who is speaking directly to us. Trusting that our curiosity about what is going on in the poem will keep us reading despite our lack of information about the character of the auditor, Browning leaves us only one source for that information, the Duke's monologue. [Adapted from Glenn Everett, "You'll Not Let Me Speak": Engagement and Detachment in Browning's Monologues"] http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/rb/dm1.html