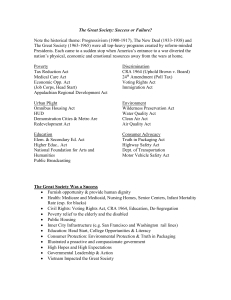

Poverty and Welfare Systems - WS 2010

advertisement

Poverty and Welfare Systems 1. What is this unit about? Poverty is a condition that most young Austrian students will have trouble imagining or relating to, so parts of this unit were chosen to give you a sense of what life is like for the poor. They also raise the question "What do poor people have to do with me?" The first exercise in this unit will illustrate the scope of the problem worldwide and should show just how privileged we are. From there we will focus on the cycle of poverty in the United States and the ideological shift from "welfare" to "workfare". In this section we will focus specifically on the relationships between poverty and crime, race, gender, and (un)employment. Two questions to consider here are what factors keep people poor and whether work is the way for them to rise out of poverty. That will lead us to the next major group of poor people in the States: the working poor. Here we will discuss what life is like on a minimum wage job based on the book Nickle- and Dimed by Barbara Ehrenreich and with scenes from the documentary Walmart: The High Cost of Low Prices. We will take a look at our own financial situations to see if we could survive on $7 an hour. Finally, we will debate the idea of the government providing a guaranteed income for all its citizens as an alternative to the many and diverse forms assistance that exist now. 2. Poverty around the World If our world were a village of 1000 people, what would its ethnic and religious composition be? How many people would be... Asian? European? African? South American? North American? _______ _______ _______ _______ _______ How many people would be ... Moslems? Christians? Atheists (or w/o religion)? Hindus? Buddhists? Jews? Other? (e.g. Animists) _______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ ______ How many would control ¾ of the total income? _____ How many of these people would be hungry? _____ How many of them would live in sub-standand housing? _____ How many would have access to clean water? _____ How many would be college educated? _____ How many of them would be illiterate (couldn’t read)? _____ Social and Economic Issues: Poverty and Welfare Systems – WS 2010/11 Page 1 3. The Cycle of Poverty What makes it so difficult – particularly for the urban poor - to rise up out of poverty? Take the list of conditions below, pick any two and write statements to express the causal relationships between them. For example, “As financial difficulties are the number one cause for divorce, living in poverty often leads to a breakdown of the family.” Write at least five sentences and try to show how these problems are cyclical. (A B C D A) Living in a Ghetto Family breakdown Proximity to Crime Lack of job skills Gangs Unemployment Lack of insurance Poor education Poor housing Lack of positive role models Accessibility to drugs Poor work ethics Violence Poor health / nutrition Social and Economic Issues: Poverty and Welfare Systems – WS 2010/11 Page 2 4. Punishing the Poor - Reading 1 About: PUNISHING THE POOR THE NEOLIBERAL GOVERNMENT OF SOCIAL INSECURITY By Loïc Wacquant (2009) Loic Wacquant is a French sociologist and professor at UC Berkeley. For over twenty years, he has been studying the convergence of changes in economic policy, welfare systems, and penal policy (policing and prisons). His most recent book makes the case that the following trends are closely linked: 1) neoliberalism on the rise, with governments mandating submission to the "free market" and celebrating "individual responsibility" in all realms; employment has become increasingly insecure (read "flexible") and social "welfare" has been transformed into "workfare" (mostly for the women – for an example of this, see Point #5 below) and what he calls "prisonfare" for men, due to 2) a dramatic expansion of prison systems and law enforcement which is punitive and proactive, "targeting street delinquency and the categories trapped in the margins and cracks of the new economic and moral order" . In other words, the newly emerging policy is to criminalize poverty and to use the justice system rather than a social welfare system to deal with the poor. Rather than dealing with the root causes of poverty, the state uses its resources to "clean-up" its aftermath and, as far as possible, to remove and contain the poor away from the rest of society through "ghettoization" and incarceration. Ironically, this opens up a lot of economic opportunity (a prison industry) while artificially reducing the unemployment rate (prisoners do not count as job seekers). "The US prison system employs seven times more people than IBM. The correctional services system in California alone has 45,000 employees - twice as many as Microsoft. From 1980 to 1990, government expenditure on public housing in the US fell by more than half, while expenditure on operating penal establishments more than doubled. And this trend continues: indeed, argues Loïc Wacquant, "the construction of prisons has effectively become the country's main housing programme". Prisons are multiplying so quickly that it is proving impossible to recruit enough personnel to staff them at a pace that keeps up with the frenzied building programme."1 One policy cited by Wacquant as an example of targeting the poor is the American "War on Drugs." He calls it "a search and destroy mission" and a tool used to round up undesirable groups and herd them into the contained space of prisons, separating them from the rest of "good" society. This policy started under Reagan in the 1980s at the same time that cuts to social welfare programs became popular, and the combined effects on the imprisonment rate of the US are inarguable, as can be seen in the charts below: 1 Hardwick, Louise, "Book of the Week: Punishing the Poor," Times Higher Education, August 6, 2009, URL: http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story.asp?storycode=407630, Accessed April 2010 Social and Economic Issues: Poverty and Welfare Systems – WS 2010/11 Page 3 Such a profound change can only be made acceptable to a society if it adopts a Social Darwinist view and sees criminality in purely individual terms (independent of a social context): "If crime has no social context and issues solely out of aberrant individual volition, then proactive social provision will only pander to the "welfare addict"; thus reactive criminal punishment is perceived as the only option. Here Wacquant deploys Pierre Bourdieu's model of the two-handed state. The state's left hand is its social aspect, proffering such provision as healthcare, social assistance and public housing. Its right hand is its penal aspect, pushing law enforcement through the courts and the police. And in contemporary America, the left hand does not know what the right is doing - but the right certainly knows what the left is doing, because it grips and controls it."2 The public must also be convinced that such harsh and pervasive punitive measures are necessary, and this work is accomplished to a large extent by politicians and the media. "With the help of the media, public attention is directed not at the massive transfer of wealth to the top of the social stratification ladder but rather on designated “incorrigible” deviants: welfare cheats and parasites, criminals and pedophiles against whom the ever-more intrusive mechanisms of the surveillance society are applied. Of course, this all is based on a series of lies that nonetheless produced and dispersed throughout society, mostly, again, through the media: that the US is spending enormous amounts of money on welfare (False: AFDC never accounted for more than 1% of the federal budget) or that crime is on rise, perpetrated by ever younger and more dangerous “predators”. Here again, this is false: crime has been on the decline for a long time irrespective of the policies implemented or not. See below, for instance as Americans still believe that there is MORE crime (and by that, they think street crime):3 2 Ibid. "Book Review – Punishing the Poor", The Global Sociology Blog, URL: http://globalsociology.com/2009/10/25/book-review-punishing-the-poor/ , Accessed April 2010 3 Social and Economic Issues: Poverty and Welfare Systems – WS 2010/11 Page 4 Sources:http://www.gallup.com/poll/123644/Americans-Perceive-Increased-Crime.aspx andBureau of Justice Statistics - http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/index.cfm?ty=kfa Wacquant's major focus is on the US, but he also argues that these changes are increasingly to be found in Western European countries: [He] also demonstrates that this double regulation of poverty (through workfare and prisonfare) has been exported to Europe, starting with the liberalization of the state through Thatcherism in the UK, the Kohl years in Germany and the oh-so memorable Chirac years as PM in France. Even the various left-of-center parties, such as the socialist parties in Western Europe have embraced the law-and-order view of the state and neoliberal economic “reforms” all the way to Sarkozy’s slogan to “work more to earn more”… we all know what happened to that in these past years. 4 He identifies six characteristics that are common to these systems, many of which can be recognized to some degree here in Austria as well: 1) putting an end to the "era of leniency" necessitating . . . 2) ever more laws, bureaucratic innovations and technological gadgets: crime-watch groups (…) video surveillance cameras (…) compulsory drug testing, (…) satellite-aided electronic monitoring, and generalized genetic finger-printing, more and larger prisons and specialized detention centers (for foreigners waiting to be expelled . . .) 3) the need for these punitive policies is conveyed everywhere by an alarmist, even catastrophist discourse on "insecurity," (…) broadcast to saturation by the commercial media, the major political parties, and professionals in the enforcement of order (…) who vie to propose drastic and simplistic solutions 4 Ibid. Social and Economic Issues: Poverty and Welfare Systems – WS 2010/11 Page 5 4) the repression and [stigmatization of] youths from declining working-class neighborhoods, the jobless, homeless, beggars, drug addicts and street prostitutes, and immigrants from the former colonies of the West . . . 5) the therapeutic philosophy of 'rehabilitation' is more or less replace by a managerialist approach centered on the cost, opening the way for the privatization of prisons 6) an extension and tightening of the police dragnet, harsher and quicker judicial procedures, and an increase in the population under lock In conclusion, two quotes from Wacquant himself: "These punitive policies are the object of an unprecedented political consensus and enjoy broad public support cutting across class lines, boosted by the tenacious blurring of crime, poverty, and immigration in the media as well as by the constant confusion between insecurity and the "feeling of insecurity." This confusion is tailor-made to channel toward the (dark-skinned) figure of the street delinquent the diffuse anxiety caused by a string of interrelated social changes: the dislocations of wage work, the crisis of the patriarchal family and the erosion of traditional relations of authority among sex and age categories, the decomposition of established workingclass territories and the intensification of school competition as requirement for access to employment. And how would the rolling out of the penal arm of the state not be popular when the parties of the governmental Left in all of the postindustrial countries have converted to a narrowly behaviorist and moralistic Rightist vision that counterposes "individual responsibility" and "sociological excuses" in the name of the (electoral) "reality principle"? It follows that penal severity is now presented virtually everywhere and by everyone as a healthy necessity, a vital reflex of self-defense by a social body threatened by the gangrene of criminality, no matter how petty." (...) Thus the "invisible hand" of the unskilled labor market, strengthened by the shift from welfare to workfare, finds its ideological extension and institutional complement in the "iron fist" of the penal state, which grows and redeploys in order to stem the disorders generated by the diffusion of social insecurity and by the correlative destabilization of the status hierarchies that formed the traditional framework of the national society (such as the division between whites and blacks in the United States and between nationals and colonial immigrants in Western Europe). The regulation of the working classes through what Pierre Bourdieu calls "the Left hand" of the state, that which protects and expands life chances, represented by labor law, education, health, social assistance, and public housing, is supplanted (in the United States) or supplemented (in the European Union) by regulation through its "Right hand," that of the police, justice, and correctional administrations, increasingly active and intrusive in the subaltern zones of social and urban space. And, logically, the prison returns to the forefront of the societal stage, when only thirty years ago the most eminent specialists of the penal question were unanimous in predicting its waning, if not its disappearance."5 5 Wacquant, Loic, Punishing the Poor, Duke University Press, 2009, URL: http://search.barnesandnoble.com/Punishing-the-Poor/Loic-Wacquant/e/9780822344223#CHP Social and Economic Issues: Poverty and Welfare Systems – WS 2010/11 Page 6 5. An example of a "Workfare" (as opposed to "welfare") system The state of Wisconsin was one of the first to implement a workfare system in 1997 and as you will see, its main objectives, ideology, and outcomes correspond to the themes that Wacquant is discussing. On the website of the Wisconsin state government, the program is introduced like this: Wisconsin Works (W-2) Overview A Place for Everyone, a System of Employment Supports Wisconsin Works (W-2) replaced Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) in September, 1997. W-2 is based on work participation and personal responsibility. Under W-2, there is no entitlement to assistance, but there is a place for everyone who meets eligibility requirements and is willing to work to their ability. The program is available to low-income parents with minor children. Each W-2 eligible participant meets with a Financial and Employment Planner (FEP), who helps the individual develop a self-sufficiency plan and determine his or her place on the W-2 employment ladder. The ladder consists of four levels of employment and training options, in order of preference . . . Source: http://dcf.wisconsin.gov/w2/wisworks.htm Notice that cash payments are not a part of this system and personal responsibility (or the willingness to work) is the central idea. Other key aspects of this reform are that 1) there is a time limit to participation in this program of 5 years, 2) it aims not to change the financial situation of the participants, but to change their behaviour, 3) it separates child support programs from the welfare (or workfare) system, and 4) it allows the participation of forprofit organizations in offering these services. In line with Wacquant's analysis, about 95% of the program's participants are female: Table 2. W-2 Participants by Gender, December, 1998 – 2003 Gender Female Male 1998 # 12,663 427 % 97% 3 1999 # 10,809 360 % 97% 3 2000 # % 10,554 96% 430 4 2001 # % 11,693 95% 566 5 2002 # % 13,407 95% 730 5 2003 # % 14,200 95% 797 5 Source: CARES, Department of Workforce Development, Bureau of Workforce Information And what about the men? . . . "The United States has had the highest incarceration rate in the world following the collapse of the Soviet Union. The general level of incarceration in this country hovered around 100 per 100,000 persons for fifty years until the 1980s and 90s, when it shot up to nearly 500 per by the turn of the century. Moreover, there is a disproportionate number of people of color in prisons incarcerated. With about 2.5% of African Americans in prison, and twelve percent of black men in their twenties or early thirties incarcerated, these rates Social and Economic Issues: Poverty and Welfare Systems – WS 2010/11 WI Jail Population: Gender Admissions by Gender 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Males Females 1992 2002 Adult Jail Populations in Wisconsin - 2002 Page 7 are almost eight times higher than among whites. This trend is pronounced in Wisconsin, with incarceration rates for blacks nearly twelve times higher, and at a higher rate of increase, due to the role of higher admission rates, more probation and parole revocations, and more drug offense sentences." Sources: "Incarcerated in Wisconsin Jails", URL: www.uwex.edu/ces/flp/families/incarcerated.ppt and "Counting Prisoners in Wisconsin", URL: http://www.prisonpolicy.org/news/wisconsinite062204.html , accessed April 2010 Questions a. Describe the trends in the US penal system. How have the prison system / justice system expanded and diversified over recent years? How does the rate of imprisonment in the US compare to that of European nations? b. In terms of economics (and politics), what is surprising about this expansion? c. How does the expanding prison population help the economy? How does it hurt? d. What aspects of the US welfare/workfare model do leaders of other nations find attractive and why? e. Of the 6 characteristics listed (pages 5-6), what examples can you identify in Austria? f. What is the media's role in the changes that have occurred in welfare policy? g. Wacquant often refers to prisoners as "clientele." What is the significance of this name? Social and Economic Issues: Poverty and Welfare Systems – WS 2010/11 Page 8 h. America is often referred to as "the land of the free". What do you think about this statement? In what ways are poor people limited in their freedom? i. The Bill of Rights spells out those rights or freedoms that are considered universal. It does not include the right to work, the right to food, the right to shelter, the right to education, or the right to privacy. Which, if any, of these do you think should be included in a country's constitution and why? (An interesting video on this topic is President Roosevelt's speech on a "Second Bill of Rights": http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3EZ5bx9AyI4 ) j. What is problematic – particularly today in times of economic crisis - about a "right to work" being transformed into an "obligation to work"? k. Wacquant states or implies several quite controversial opinions. Five are listed below. Check whether you agree or disagree and be prepared to defend your response. Agree Disagree 1. The justice system targets the poor. 2. The purpose of ghettos and prisons is to keep marginal, undesirable or economically insignificant groups away from society. 3. There is a direct connection between social welfare / social (financial) insecurity and criminality. 4. Social welfare recipients are punished by the process. 5. The system (purposely) makes it difficult or impossible to rise up out of poverty. 6. Poverty: Race, Age, Gender and other factors Loic Wacquant (see reading above) makes a lot of assertions about the persistent problem of racism in the US police and justice system. Do these statistics mean, however, race is the deciding characteristic in a person's risk of poverty? What is the connection between race, gender, age, and family situation and a person's standard of living? A) According to the Census Bureau, in the year 2008 the average American household income was about $50,300, the poverty threshold was set at $22,000 for a four person household or $10,991 for a single person, and the overall poverty rate was 13.2%. Match the (racial, gender, age, and family) groupings to their 2008 poverty rates in the chart below. Social and Economic Issues: Poverty and Welfare Systems – WS 2010/11 Page 9 Types of households: I. Poverty Rate 3.7 II. 5.5 Single male householders III. 6.1 Single female householders IV. 8.6 V. 10.2 Whites VI. Families 10.3 Non-Hispanic Whites VII. 11.2 Blacks VIII. 11.6 Asians IX. All people 13.2 Hispanics* X. 13.8 American Indians + Alaskans XI. 19 XII. 20.8 XIII. 23.2 XIV. 23.3 Children under 18 XV. 23.6 Children under 6 XVI. 24.6 Children under 6 living with female householder XVII. 25.3 XVIII. 28.3 Bachelor's degree or more XIX. 31.4 No high school graduation XX. 54 Married couples Racial Groupings: Foreign-born citizens Foreign-born non-citizens Age Groupings: Education/Employment: Employed Unemployed * "Hispanic" is not really a racial designation. A Hispanic can be of any race. For example, about 14% of whites are of Hispanic origin. B) Based on the information in the chart, what factors have the greatest influence on a person's risk of falling below the poverty line? Do these tend to be personal characteristics or life choices? Social and Economic Issues: Poverty and Welfare Systems – WS 2010/11 Page 10 7. The Working Poor - Reading 2 Excerpts from: Nickle - and Dimed: Undercover in Low Wage USA (Granta Books, London, 2002) by Barbara Ehrenreich Barbara Ehrenreich is a well-known author and journalist. Several years ago she decided to investigate the life of minimum wage workers by becoming one herself. Over many months, she worked as a waitress, a house cleaner, a care home worker and a Walmart sales assistant in three different cities across the USA, doing her utmost to live only on her earnings and not to fall back on the comforts and advantages of her real, upper-middle class life. Through her experiences she is able to draw a vivid picture of an almost invisible class of Americans - the many hardworking, well meaning people trying to do their best in often demeaning conditions. The conclusion that she comes to is that it is not physically possible for a single person in good health to get by on the wages she is paid. A minimum wage job can not cover rent, transport and food. The only way to get by is to work two jobs or to share accomodations. What Ehrenreich has to say about . . . . . . paying the rent: (After a description of how well she performed at her various jobs, she writes) „But the real question is not how well I did at work, but how well I did at life in general, which includes eating and having a place to stay. The fact that these are two separate questions needs to be underscored right away. In the rhetorical buildup to welfare reform, it was uniformly assumed that a job was the ticket out of poverty at that the only thing holding back welfare reciptients was their ruluctance to get out and get one. I got one and sometimes more than one, but my track record in the survival department is far less admirable than my performance as a job holder. (Here follows a listing of her income and expenses in the three different cities and her inability to afford rent and food on her wages.) So the problem goes beyond my personal failings and miscalculations. Something is wrong, very wrong, when a single person in good health, a person who in addition possesses a working car, can barely support herself by the sweat of her brow. You don’t need a degree in economics to see that wages are too low and rents too high.“ (pp 197-99) „When the market fails to distribute some vital commoditiy, such as housing, to all who require it, the usual liberal-to-moderate expectation is that the government will step in and help. We accept this principle -- at least in a halfhearted and faltering way -- in the case of health care, where the government offers Medicare to the elderly, Medicaid to the desperately poor and various state programs to the children of the merely very poor. But in the case of housing, the extreme upward skewing of the market has been accompanied by a cowardly public sector retreat from responsibility. Expenditures on public housing have fallen since the 1980s, and the expansion of public rental subsidies came to a halt in the mid-1990s. At the same time, housing subsidies for home owners -who tend to be far more affluent than renters -- have remained at their usual munificent levels. It did not escape my attention, as a temporarily low-income person, that the housing subsidy I normally receive in my real life -- over $20,000 a year in the form of a mortgage interest deduction -- would have allowed a truly low-income family to live in relative splendor. Had this amount been available to me in monthly installments in Minneapolis, I could have moved into one of those „executive“ condos with sauna, health club and pool.“ (pp 200-201) . . . lack of mobility „I was baffled, initially, by what seemed like a certain lack of get-up-and-go on the part of my fellow workers. Why didn’t they just leave for a better paying job, as I did when I moved from the Hearthside Social and Economic Issues: Poverty and Welfare Systems – WS 2010/11 Page 11 to Jerry’s? Part of the answer is that actual humans experience a little more „friction“ than marbles do, and the poorer they are, the more constrained their mobility usually is. Low-wage people who don’t have cars are often dependent on a relative who is willing to drop them off and pick them up again each day, sometimes on a route that includes the babysitter’s house or the child care center. Change your place of work and you may be confronted with an impossible topographical problem to solve, or at least a reluctant driver to persuade. Some of my coworkers, in Minneapolis as well as Key West, rode bikes to work, and this clearly limited their geographical range. For those who do possess cars, there is still the problem of gas prices, not to mention the general hassle, which is of course far more onerous for the carless, of getting around to fill out applications, to be interviewed, to take drug tests. I have mentioned too, the general reluctance to exchange the devil you know for one that you don’t know, even when the latter is tempting you with a better wage-benefit package. At each new job, you have to start all over, clueless and friendless . . . (p. 205) . . . conditions and indignities of the low wage workplace But if it’s hard for workers to obey the laws of economics by examining their options and moving on to better jobs, why don’t more of them take a stand where they are -- demanding better wages and work conditions, either individually or as a group? This is a huge question, probably the subject of many a dissertation in the field of industrial psychology, and here I can only comment on things I observed. One of these was the co-optative power of management, illustrated by such euphemisms as associate and team-member. At The Maids, the boss -- who, as the only male in our midst, exerted a creepy, paternalistic kind of power -- had managed to convince some of my coworkers that he was struggling against difficult odds and deserving of their unstinting forbearance. Wal-Mart has a number of more impersonal and probably more effective ways of getting ist workers to feel like „associates“. There was the profit-sharing plan, with Wal Mart’s stock price posted daily in a prominent spot near the break room. There was the company’s much heralded patriotism, evidenced in the banners over the shopping floor urging workers and customers to contribute to the construction of a World War II veterans’s memorial (Sam Walton having been one of them). There were „associate“ meetings that served as pep rallies, complete with the Wal-Mart cheer: „Gimme a W, etc.. The chance to identify with a powerful and wealthy entity --the company or the boss -- is only the carrot. There is also a stick. What surprised and offended me most about the low-wage workplace (and yes, here all my middle class privilege is on full display) was the extent to which one is required to surrender one’s basic civil rights and -- what boils down to the same thing -- self-respect. I learned this at the very beginning of my stint as a waitress, when I was warned that my purse could be searched by management at any time. I wasn’t carrying stolen salt shakers or anything else of a compromising nature, but still, there’s something about the prospect of a purse search that makes a woman feel a few buttons short of fully dressed. After work, I called around and found that this practice is entirely legal: if a purse is on the boss’s property -- which of course it was -- the boss has the right to examine ist contents. Drug testing is another routine indignity. Civil-libertatians see it as a violation of our Fourth Amendment freedom from „unreasonable search“; most jobholders and applicants find it simply embarrassing. In some testing protocols, the employee has to strip to her underwear and pee into a cup in presence of an aide or technician. Mercifully, I got to keep my clothes on and shut the toilet stall door behind me, but even so, urination is a private act and it is degrading to have to perform it at the command of some powerful other . . . There are other, more direct ways of keeping low-wage employees in their place. Rules against „gossip“ or even „talking“ make it hard to air your grievances to peers or -- should you be so daring -- to enlist other workers in a group effort to bring about change, through a union organizing drive, for example. Those who do step out of line face little unexplained punishments, such as having their schedules or their work assigments unilaterally changed. Or you may be fired: those low-wage workers who work without union contracts, which is the great majority of them, work „at will“, meaning at the will of the employer, and are subject to dismissal without explanation. So if low-wage workers do not always behave in an economically rational way, that is, as free agents withing a capitalist democracy, it is because they dwell in a place that is neither free nor in any way democratic. When you enter the low-wage workplace -- any many of the medium-wage workplaces as well -- you check your civil liberties at the door, leave America and all it supposedly stands for behind, and learn to zip your lips for the duration of the shift. The consequences of this routine surrender go beyond issues of wages and poverty. We can hardly pride ourselves on being the world’s preeminent Social and Economic Issues: Poverty and Welfare Systems – WS 2010/11 Page 12 democracy, after all, if large numbers of citizens spend half their waking hours in what amounts, in plain terms, to a dictatorship.“ (pp 205-210) . . . humanity and inhumanity „My guess is that these indignities imposed on so many low-wage workers -- the drug tests, the constant surveillance, being „reamed out“ by managers -- are part of what keeps wages low. If you’re made to feel unworthy enough, you may come to think that what your’re paid is what you are actuallly worth. It is hard to imagine any other function for workplace authoritarianism. Managers may truly believe that, without their unremitting efforts, all work would quickly grind to a halt. That is not my impression. While I encountered some cynics and plenty of people who had learned to budget their energy, I never met an actual slacker or, for that matter, a drug addict or thief. On the contrary, I was amazed and sometimes saddened by the pride people took in jobs that rewarded them so meagerly, either in wages or in recognition. Often, in fact, these people experienced management as an obstacle to getting the job done as it should be done. . . . Left to themselves, they devised systems of cooperation and work sharing; when there was a crisis, they rose to it. In fact, it was often hard to see what the function of management was, other than to exact obeissance.“ pp 211-212 . . . living wages „But whatever keeps wages low --and I am sure my comments have barely scratched the surface -- the result is that many people earn far less than they need to live on. How much is that? The Economic Policy Institute recently reviewed dozens of studies of what constitutes a „living wage“ and came up with an average figure of $30,000 a year for a family of one adult and two children, which amounts to a wage of $14 an hour. This is not the very minimum such a family could live on; the budget includes health insurance, a telephone, and child care at a licensed center, for example, which are well beyond the reach of millions. But it does not include restaurant meals, video rentals, Internet access, wine and liquor, cigarettes and lottery tickets, or even very much meat. The shocking thing is that the majority of American workers, about 60%, earn less than $14 an hour. Many of them get by by teaming up with another wage earner, a spouse, or a grown child. Some draw on government help in the form of food stamps, housing vouchers, the earned income tax credit, or -- for those coming off welfare in relatively generous state -- subsidized child care. But others -- single mothers, for example -- have nothing but their own wages to live on, no matter how many mouths there are to feed. Employers will look at that $30,000 figure, which is over twice what they currently pay entry-level workers, and see nothing but bankruptcy ahead. Indeed, it is probably impossible for the private sector to provide everone with an adequate standard of living through wages, or even wages plus benefits, alone: too much of what we need, such as reliable child care, is just too expensive, even for middle class families. Most civilized nations compensate for the inadequacy of wages by providing relatively generous public services such as helath insurance, free or subsidized child care, subsidized housing, and effective public transportation. But the United States, for all ist wealth, leaves it citizens to fend for themselves -- facing market-based rents, for example, on their wages alone. For millions of Americans, that $10 -- or even $8 or $6 -- hourly wage is all there is. It is common, among the nonpoor, to think of poverty as a sustainable condition -- austere, perhaps, but they get by somehow, don’t they? They are „always with us.“ What is harder for the nonpoor to see is poverty as acute distress: The lunch that consists of Doritos or hot dog rolls, leading to faintness before the end of the shift. The „home“ that is also a car or a van. The illness or injury that must be „worked through,“ with gritted teeth, because there’s no sick pay or health insurance and the loss of one day’s pay will mean no groceries for the next. These experiences are not part of a sustainable lifestyle, even a lifestyle of chronic deprivation and relentless low-level punishment. They are, by almost any standard of subsistence, emergency situations. And that is how we should see the poverty of so many millions of low-wage Americans -- as a state of emergency.“ (pp 213-214) Social and Economic Issues: Poverty and Welfare Systems – WS 2010/11 Page 13 . . . welfare "reform "When poor single mothers had the option of remaining out of the labor force on welfare, the middle and upper class tended to view them with a certain impatience, if not disgust. The welfare poor were excoriated for their laziness, their persistence in reproducing in unfavorable circumstances, their presumed addictions, and above all for their "dependency." Here they were, content to live off "government handouts" instead of seeking "self-sufficiency," like everyone else, through a job. They needed to get their act together, learn how to wind an alarm clock, get out there and get to work. But now that government has largely withdrawn its "handouts," now that the overwhelming majority of the poor are out there toiling in Wal-Mart or Wendy's - well, what are we to think of them? Disapproval and condescension no longer apply, so what outlook makes sense? Guilt, you may be thinking warily. Isn't that what we're supposed to feel? But guilt doesn't go anywhere near far enough; the appropriate emotion is shame - shame at our own dependency, in this case, on the underpaid labor of others. When someone works for less than she can live on - when, for example, she goes hungry so that you can eat more cheaply and conveniently - then she has made a great sacrifice for you, she has made you a gift of some part of her abilities, her health, and her life. The "working poor," as they are approvingly termed, are in fact the major philanthropists of our society. They neglect their own children so that the children of others will be cared for; they live in substandard housing so that other homes will be shiny and perfect; they endure privation so that inflation will be low and stock prices high. To be a member of the working poor is to be an anonymous donor, a nameless benefactor, to everyone else. As Gail, one of my restaurant coworkers put it, 'you give and you give.'" (pp 220-221) Questions A. What irony does Ehrenreich point out in the housing benefits the US government provides? B. In what other ways can the wealthy be the beneficiaries of government assistance ("welfare")? C. In what ways are the poor limited in their “flexibility”? D. In what ways are civil rights denied at the low-wage workplace? E. The usual conception of the poor is that they are dependent on the middle and upper classes for their survival. What does Ehrenreich say about this idea? F. If Ehrenreich is correct, then one could argue that our system requires that a substantial portion of the population lives under or near the poverty level. Become a cynic for a few minutes and list what functions the poor might fulfil in brutally capitalistic society. G. Could you live on a minimum wage job (i.e. $7 an hour and nothing else)? Use the personal budget we did as homework and keep in mind what a minimum wage job would bring in (Euros per month after taxes) and that it would not include health insurance. Social and Economic Issues: Poverty and Welfare Systems – WS 2010/11 Page 14 8. So . . . what should the government do and what should business do? Brainstorming: How can the problems above be addressed? In a group, come up with ideas that could help break the cycle of poverty and decrease the disparity between different groups of people. Make a clear distinction between what efforts should be made in the public sector and which in the private sector. What governments should do What business should do 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 5 Social and Economic Issues: Poverty and Welfare Systems – WS 2010/11 Page 15 9. A Guaranteed Income? After looking at depth into the issue of poverty, we will debate the idea of a guaranteed income in class. Read the passage below, which describes the proposal for the government to pay a certain income to all citizens. Keep in mind that this system would replace all the many individual-case benefits being offered at the moment as well as the pension system, family and child supports, etc. Weigh the advantages and disadvantages of such a system and then decide which side of the debate you will argue. Would you support such a proposal in principle? Yes or no? (from David Korten's, When Corporations Rule the World) "Guaranteed Income. An idea long popular with both conservative and progressive economists, a guaranteed income merits serious consideration. It involves guaranteeing every person an income adequate to meet his or her basic needs. The amount would be lower for children than for adults but would be unaffected by a person's other income, wealth, work, gender, or marital status. It would replace social security and existing welfare programs. Since earned income would not reduce the guaranteed payment, there would be little disincentive to work for pay. Indeed, if some people chose not to work at all, this should not be considered a serious problem in labor-surplus societies. Although some wages would no doubt fall, employers might have to pay more to attract workers to unpleasant tasks. It would allow greater scope for those who wish to do unpaid work in the social economy. Such a scheme would be expensive, but could be supported in most high-income countries by steep cuts in military spending, corporate subsidies, and existing entitlement programs and by tax increases on upper income, luxuries, and the things a sustainable society seeks to discourage. Combined with an adequate program of universal publicly funded health insurance and merit-based public fellowships for higher education, a guaranteed income would greatly increase the personal financial security afforded by more modest incomes. In low income countries, agrarian reform and other efforts to achieve equitable access to productive natural resources for livelihood production might appropriately substitute for a guaranteed income." (p.318) Suggestions for extra reading / independent work: o If you are not clear about the terms "Mindestsicherung" and "Grundeinkommen", these concepts are defined and the positions of the Austrian political parties are summarized in the following report from the Ö1/ORF: Grundeinkommen für alle - Idee umstritten Link to article and audio: http://oe1.orf.at/inforadio/95963.html?filter= o A similar proposal (called "Bürgergeld") was made by the CEO the company DM, Werner Götz, in an interview in 2005. You can find this interview - ""Die Wirtschaft befreit die Menschen von der Arbeit" – under extra materials on the homepage. (http://www.uni-graz.at/~pommer/be2materials/Buergergeld-durch-MWSt.pdf ) Social and Economic Issues: Poverty and Welfare Systems – WS 2010/11 Page 16