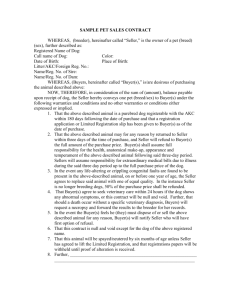

Sale

advertisement