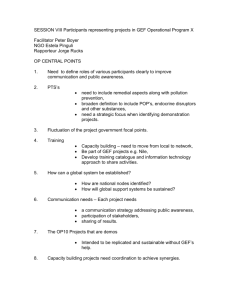

Project Implementation - Global Environment Facility

advertisement