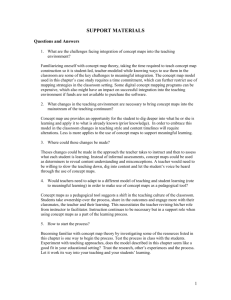

Hay_Final_Report.doc - Higher Education Academy

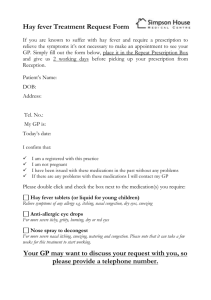

advertisement