Evaluation of the National Indigenous Ear Health Campaign

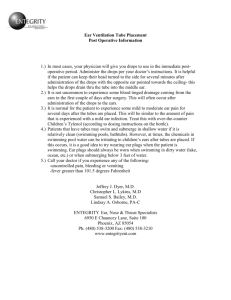

advertisement