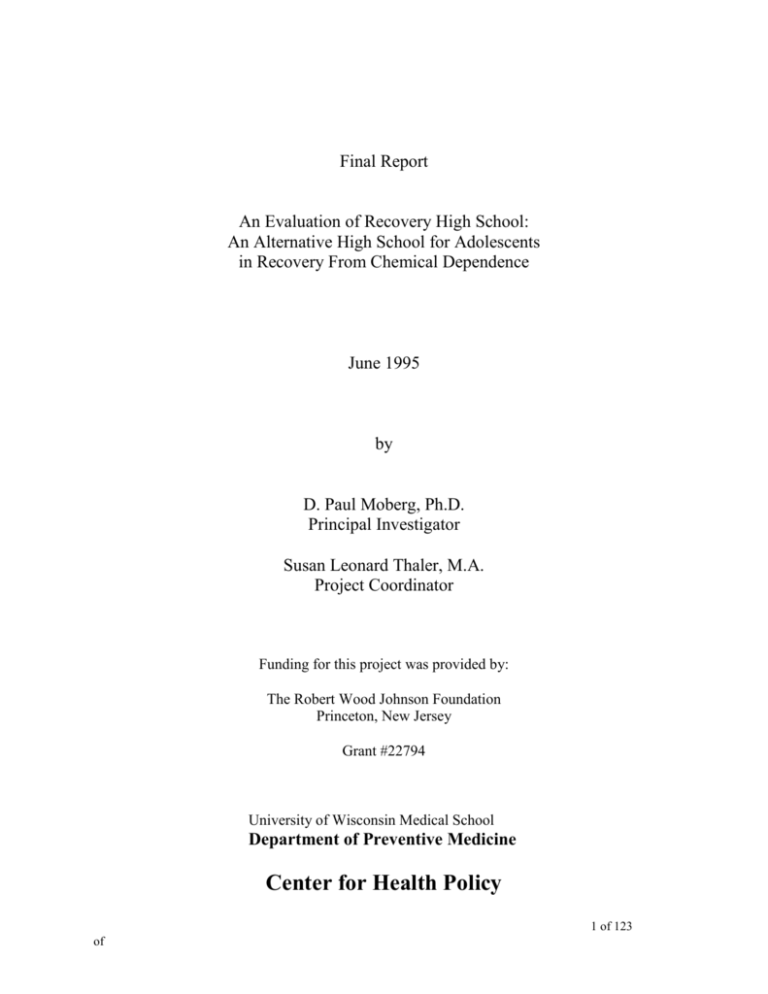

Formal 1995 report by Paul Moberg and Susan Leonard Thaler on

advertisement