Handbook of digital advertising.doc - News

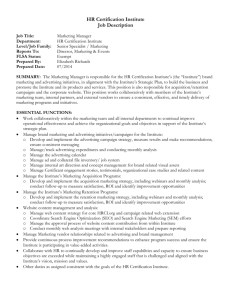

advertisement