Censorship, Logocracy and Democracy

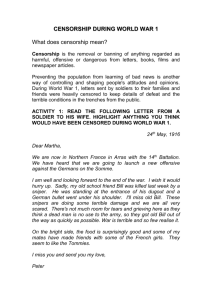

advertisement