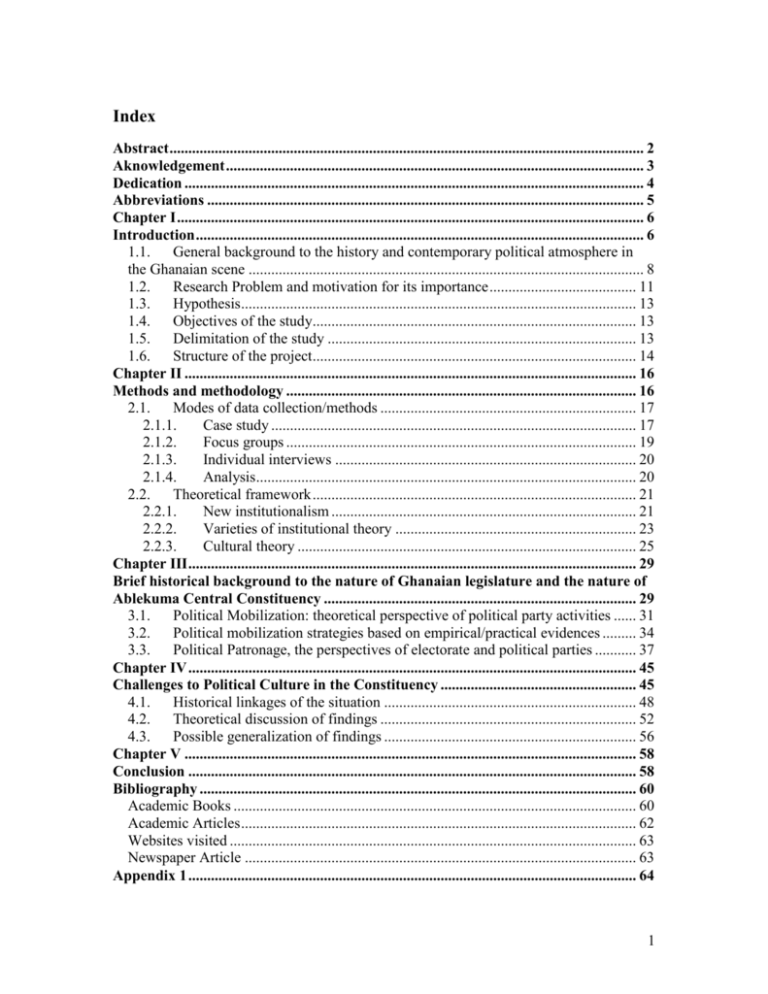

Political mobilization and patronage in Ghana, the case of

advertisement