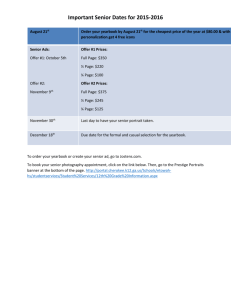

Click here to see a copy of the original ACLU

advertisement

May 7, 2003 Dr. Joan Sergent, Superintendent Utica Community Schools 11303 Greendale Sterling Heights, MI 48312-2925 Re: VIA FIRST CLASS MAIL AND FACSIMILE (586-797-1101) Abbey Moler Dear Dr. Sergent: The American Civil Liberties Union Fund of Michigan would like to meet with you at your earliest convenience to discuss and resolve amicably an issue which arose at Stevenson High School: the School’s removal of Abbey Moler’s selection of a biblical reference from the “wants to pass on” section of the 2001 yearbook. Some background information, as provided by the Moler family, may be helpful to explain the ACLU’s position and concerns in this matter. As you may be aware, Abbey Moler was the Class Valedictorian – the very first in her class – at Stevenson High School, when she graduated in June, 2001. As such, Ms. Moler was invited, just as previous valedictorians had been, to give advice to fellow students in a “wants to pass on” section of the yearbook. Ms. Moler was not informed of any restrictions or criteria for the advice which she could give. Upon careful reflection guided by her own principles and convictions, submitted the following: I would like to share a favorite verse that shapes my life and guides me from day to day: “‘For I know the plans I have for you,’ declares the Lord, ‘plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.’” Jeremiah 29:11 (New International Bible). Months later, without notifying Ms. Moler that there may have been a problem with her selection of advice to other students, the school published the yearbook with a critical omission. The yearbook did not contain Ms. Moler’s selection of advice. (See Valedictorian & Salutatorians pages of 2001 Yearbook, Exhibit A). It was only after Ms. Moler’s mother picked up her daughter’s yearbook, that Ms. Moler learned the school had censored her choice of words. Two explanations for the omission were offered by the yearbook adviser, Nicole Faricy. First, Ms. Faricy explained, the words chosen by Ms. Moler could not be published because they were religiously offensive. Second, Ms. Faricy explained, the decision to remove Ms. Moler’s choice of words was necessary due to the decision in Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier, 484 U.S. 260 (1988), a case which concluded that a school principal retained the right to impose restrictions on a newspaper published by students as part of their journalism class if it served a “legitimate pedagogical interest.” Ms. Faricy further suggested that allowing a biblical quotation in the yearbook would violate the Establishment Clause’s prohibition on state-sponsored religion. As I am sure you know, the ACLU maintains a firm commitment to upholding the Establishment Clause, which guarantees the separation between church and state. Ironically, the decision to censor Ms. Moler’s passage may have even been motivated, at least in part, by a fear of a lawsuit from the ACLU. However, in this case, we believe that Ms. Faricy misapprehended the relevant law in deciding to remove Ms. Moler’s choice of a biblical quotation from the portion of the yearbook where Ms. Moler was explicitly permitted to express her personal thoughts. Ms. Faricy may have thought she had to suppress all expression of a religious viewpoint in the yearbook to avoid an Establishment Clause violation. However laudable her goals, school officials may not, as a general matter, discriminate against the private expression of religious viewpoints without violating the free speech clause of the First Amendment. We would like to explain how these constitutional principles should be reconciled, and how the School’s procedures could be revised to avoid the unfortunate result here in the future. At the outset, we should restate the governing test for ensuring that a governmental entity such as a school does not “endorse” a particular religion. In the landmark case of Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602 (1971), the U.S. Supreme Court held that state subsidies to teachers of secular subjects in non-public schools violated the Establishment Clause. In reaching this decision, the Court created a test for whether the statute providing the subsidies was unconstitutional: “the statute must have a secular legislative purpose; . . . its principal or primary effect must be one that neither advances nor inhibits religion; . . . [and] the statute must not foster ‘an excessive government entanglement with religion.’” 403 U.S. at 612-613. The so-called “Lemon test” has been applied by the courts to public schools such as Stevenson High. In the case of Lee v. Weisman, 505 U.S. 577 (1992), the U.S. Supreme Court found a violation of the Establishment Clause where the school invited members of clergy to offer prayers at a public school graduation ceremony. The participation of clergy in the effectively mandatory graduation ceremony fostered an excessive government entanglement with religion. As Justice Kennedy explained: “It is beyond dispute that, at a minimum, the Constitution guarantees that government may not coerce anyone to support or participate in religion or its exercise.” 505 U.S. at 587. 2 However, the U.S. Supreme Court has distinguished situations other than graduation ceremonies where the school opens a portion of its facilities or programs to students’ individual expression: thereby creating a limited public forum for speech. In Good News Club v. Milford Central School, 121 S. Ct. 2093 (2001), the U.S. Supreme Court held that where certain clubs were meeting after school hours and were not sponsored by the school, the school’s exclusion of a Christian club for children meeting on school premises violated club members’ free speech rights. Id., 111-112. The court further held that public schools would not violate the Establishment Clause by permitting religious groups to use school facilities on an equal basis as other groups because it would be treating all viewpoints neutrally. Id., 114. Here, as in Good News Club, Ms. Moler’s selection of a biblical quotation did not risk the appearance of school sponsorship precisely because the quotation was to be placed in a limited portion of the yearbook designated for high-achieving students to express their thoughts. As such, Ms. Moler was simply expressing her thoughts in a limited public forum for purposes of the First Amendment – proscribable only where the speech would “substantially interfere with [the school’s] work . . . or impinge upon the rights of other students.” Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, 484 U.S. 260, 271 (1988) (quoting Tinker v. Des Moines Indep. Comm. School District, 393 U.S. 503, 511 (1969)). Because Ms. Faricy removed the biblical quotation evidently on the basis of its religious viewpoint, the removal is presumptively unconstitutional. Good News Club, supra, 111-112. Ms. Faricy’s reliance on Hazelwood as justification for removing Ms. Moler’s submission is misplaced. In Hazelwood, the Supreme Court held that a school principal could constitutionally impose reasonable restrictions on the speech of student journalists who were writing articles for a school-sponsored newspaper as part of a class. There were two major rationales for this holding. First, articles written by students as part of the curriculum could reasonably be perceived as “bear[ing] the imprimatur of the school.” Id. at 271. Second, when a newspaper is being produced as part of the curriculum, educators are entitled to exercise greater control over student expression to “assure that participants learn whatever lessons the activity is designed to teach.” Id. Thus, school officials may choose to refuse to print articles by student journalists that is, “for example, ungrammatical, poorly written, inadequately researched, biased or prejudiced, vulgar or profane, or unsuitable for immature audiences.” Id. Given that the Stevenson High School yearbook is produced as part of a class, Ms. Moler recognizes that the majority of the yearbook is governed by the Hazelwood standards. However, the “wants to pass on” section of the yearbook is different. First, there can be no doubt that the couple of lines in the yearbook reserved for the valedictorian’s advice to others is the speech of the valedictorian, and the valedictorian alone. In other words, unlike the rest of the yearbook, these words cannot reasonably be confused with speech of the school. Second, unlike the rest of the yearbook, the students who make submissions to the “wants to pass on” section of the yearbook are not making these submissions as students in the yearbook class. To the contrary, the school has opened up a forum for certain high-achieving students to give what advice they think appropriate. One only needs to look at some of the “questionable” 3 submissions to this section in past years to recognize that quality of advice has not always been very high and that the school has given students the freedom to express themselves as the students see fit.1 See Kincaid v. Gibson, 236 F.3d 343, 349 (6th Cir. 2001) (To determine whether the government intended to create a limited public forum, the government’s practice “speaks louder than words.”). In short, the Hazelwood standard does not apply to the “wants to pass on” section of the valedictorian page since it does not bear the imprimatur of the school and the speakers are not part of a class, but rather high-achieving students invited to offer their own nuggets of wisdom. Moreover, even if one were to argue that Hazelwood standards did apply to the “wants to pass on” section, the censorship was still unconstitutional. Hazelwood does not grant unlimited censorship authority to school officials. Rather, educators may control the style and content of student journalists’ work in school-sponsored publications only to the extent that “their actions are reasonably related to legitimate pedagogical concerns.” Id. at 273 (emphasis supplied). In the present case, there are no legitimate pedagogical or educational reasons to discriminate against a student’s personal advice to her classmates that contains a religious message. The concerns expressed about the articles in Hazelwood – that one article did not meet high journalistic standards and another article was inappropriate for younger students and could be harmful to pregnant students – are simply not present here. Rather, the censorship in this case was based solely on the speaker’s religious views or opinion which cannot be characterized as harmful or lacking journalistic standards. Not everyone may agree with her views, but that is not sufficient reason to censor them. Even in nonpublic forums, censorship cannot be based on a speaker’s viewpoint.2 See Kincaid v. Gibson, 236 F.3d 342, 356 (6th Cir. 2001), citing Perry For example, Sean Corcoran provided the following advice in the “Wants to pass on” section of the 2001 yearbook: “Do well so you can leave.” (Exhibit A). In the 1998 yearbook, Nicholas Stone gave some equally frivolous parting words: “I’ll never grow old, I’ll never die, and I’ll always eat oatmeal.” (See Exhibit B). That same year, Katherine Walowicz took a line from the movie The Graduate as words of wisdom: “One word: Plastics.” (Exhibit B). Interestingly, in 1998, Andrew Park was permitted to make a reference to God in his words of advice: “God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change those I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.” (Exhibit B). As with Abbey Moler’s passage, nobody could reasonably mistake Mr. Park’s advice as an endorsement of religion by the school. 1 It should be noted that when the government creates a limited public forum, it “is not required to engage in every type of speech. The state may be justified ‘in reserving [its forum] for certain groups or for the discussion of certain topics.” Good News Club, supra, 106 (citation omitted). Therefore, school officials may constitutionally restrict the “wants to pass on” section to the giving advice. Also, because the speech is in a school setting, school officials may prohibit lewd language, Bethel School Dist. No. 403 v. Fraser, 478 U.S. 675 (1986), speech encouraging use of alcohol or drugs, or any speech that would “substantially interfere with the work of the school or impinge on the rights of other students.” Tinker, 478 U.S. at 509. However, it is clear that school officials may not restrict private speech simply because it advances a religious viewpoint. Good News Club, supra, 106-107, 112; also see Rosenberger v. 4 2 Educ. Ass’n v. Perry Local Educators’ Ass’n, 460 U.S. 37, 46 (1983). To the best of our research, there has been one case similar to the situation faced by Ms. Moler. In Stanton v. Brunswick School Department, 577 F. Supp. 1560 (Me. 1984), a federal district court issued injunctive relief in favor of a student whose selected quotation to be placed in the school yearbook was removed by the school. The court recognized that the portion of the yearbook at issue was a limited public forum in which students could share their views. The school could not, consistent with the First Amendment, censor the student’s speech from that portion of the yearbook based on the content of the speech. In a nutshell, the Constitution requires school officials to remain neutral in maters of religion. Rosenburger v. Rector and Visitors of University of Virginia, 515 U.S. 819, 839 (1995). They may not endorse or encourage one religion over another and they may not endorse religion over non-religion. However, by the same token, neutrality means that school officials may not suppress students’ private personal religious views so long as the expression does not disrupt the workings of the school. Rather than pursue such litigation, the ACLU would like to meet with you in order to resolve the matter of Abbey Moler by discussion and consensus. You, of course, are more than welcome to bring the school district’s attorney with you if you like. Our goals in this discussion would be, first, the creation of a school policy which contains clear rules for what may be stated in the “wants to pass on” section of the yearbook, and which does not discriminate based on the content of the students’ speech. To the extent that Stevenson High has an existing yearbook policy, please provide me with a copy of the policy prior to our meeting. Our second goal would be for Stevenson to afford Ms. Moler some relief from the unfortunate removal of her speech from the yearbook; specifically, we would ask Stevenson to place in the 2001 yearbooks on file a sticker with Ms. Moler’s choice of biblical verse as she originally elected. Ms. Moler is not seeking money damages. We would further ask that Stevenson provide Ms. Moler with a complimentary copy of the amended yearbook under cover of a letter expressing some regret in regards to the removal of her words “to pass on.” Finally, we believe that school officials and teachers would benefit from a training regarding free speech and church-state issues in the schools. In this regard, Wayne State Law School Professor Robert Sedler, who is an expert in these areas, has generously offered to speak on these topics at an in-service training without charge. Rector and Visitors of Univ. of Va., 515 U.S. 819, 831 (1995) (unconstitutional to deny funding to student group to publish journal simply because the journal was religious in nature). 5 Please contact me at your earliest convenience so that we can discuss these matters. Thank you. Very truly yours, Michael J. Steinberg cc: Abbey Moler Frank Moler Professor Robert Sedler 6