Chapter 11: The Peculiar Institution

advertisement

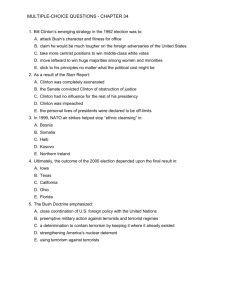

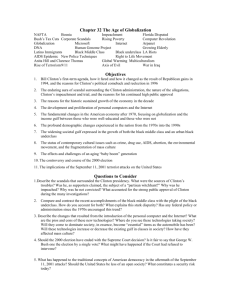

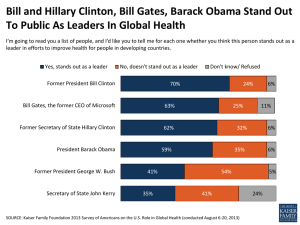

Donnelly APUSH Chapter 27: Globalization and Its Discontents, 1989–2000- Lecture Transcript In December 1999, delegates from around the world met in Seattle for a meeting of the World Trade Organization (WTO), a group of nations formed in 1994 to reduce barriers to international commerce and settle trade disputes. Surprising many, more than 30,000 participated in protests, including factory workers criticizing global free trade for encouraging U.S. corporations to move production to low-wage countries, and environmentalists complaining of the impact of unregulated economic development on the ecology. The protestors, hundreds of whom were arrested, succeeded in disrupting the WTO meeting, which was disbanded. Seattle was home to Microsoft, the computer company whose software ran most of the world’s computers. Few companies better symbolized “globalization,” the process by which people, investment, goods, information, and culture flowed across national borders. Globalization was called “the concept of the 1990s,” in which some argued that a new era in human history was at hand, with a global economy and “global civilization” replacing traditional cultures. Some argued that the nation-state itself had become obsolete. Yet globalization was not a new phenomenon. The internationalization of commerce and culture and mass migrations had occurred since at least the fifteenth century. But the scale and scope of late-twentieth century globalization was unprecedented. Thanks to new technologies, information and culture spread instantaneously throughout the world. Manufacturers and financial institutions searched the world for profitable opportunities. Perhaps most important, the collapse of communism between 1989 and 1991 opened the entire world to market capitalism and ideas that government should interfere as little as possible in the economy. The Free World had triumphed over communism, the free market over the planned economy, and the free individual over community and social citizenship. Politicians increasingly criticized economic and environmental regulation and welfare as burdens on international competition. In the 1990s, both presidents George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton spoke of an American mission to create a single world market that would raise living standards, spread democracy, and promote greater freedom in the world. Soon, more protests at economic summits followed. The media called groups who organized them the “antiglobalization” movement. Yet these groups did not challenge globalization but rather its social consequences. They argued that globalization increased wealth but also widened gaps between rich and poor countries and between haves and have-nots within societies. Decisions affecting the lives of millions of people were being made by institutions—the World Trade Organization, International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and multinational corporations—that operated without any democratic input. These international organizations required developing nations seeking financial aid to open their economies to penetration from abroad while reducing spending on domestic social concerns. Protests called not for ending global trade and capital flows, but the creation of global standards for wages, labor conditions, and the environment, and more investment in health and education in poor nations. And the Battle at Seattle placed on the United States and world agendas the most pressing concerns of the new century—the relationship between globalization, economic justice, and freedom. The year 1989 was a momentous one in twentieth-century history. In April, tens of thousands of student demonstrators occupied Tianenmen Square in Beijing, demanding greater democracy in China. Workers, teachers, and even government officials joined them and their numbers swelled to almost 1 million. Inspired by reforms in the Soviet Union and American institutions, the protesters were crushed by Chinese troops in June. An unknown number, maybe thousands, were killed. In the fall of 1989, pro-democracy protests spread throughout Europe. But under Gorbachev, this time the USSR did not suppress dissent. On November 9, crowds breached the Berlin Wall, since 1961 the Cold War’s greatest symbol, and started to tear it down. One by one, the region’s communist governments agreed to surrender power. The rapid and almost entirely peaceful collapse of communism in eastern Europe became known as the “Velvet Revolution.” But the USSR slipped into crisis. Gorbachev’s reforms caused economic crisis and brought long-suppressed national and ethnic tensions into the open. In 1990, the Baltic republics declared their independence from the USSR. In August 1991, a group of military leaders tried to seize power to reverse the government’s plan to give more autonomy to various parts of the Soviet Union, but President Boris Yeltsin organized crowds in Moscow that restored Gorbachev to power. Gorbachev resigned from the Communist Party, ending its eighty-four-year rule. Soon the USSR’s republics declared themselves sovereign states. By the end of 1991, the Soviet Union had ceased to exist and fifteen new, independent nations existed in its place. The collapse of communism marked the end of the Cold War and a great victory for the United States and its allies. For the first time since 1917, a worldwide capitalist system existed. Even China, still ruled by its Communist Party, embraced market reforms and secured foreign investments. Other events seemed to make the 1990s “a decade of democracy.” In 1990, South Africa released Nelson Mandela, the head of the African National Congress, from prison, and four years later, in that nation’s first democratic elections, he was elected president, ending South Africa’s apartheid system and white minority government. Peace came to Latin America, with negotiations bringing an end to civil war in El Salvador and elections won by opponents of the Sandinistas in Nicaragua. Civilian government replaced military regimes in much of Latin America and Africa. The move from a bipolar world to one of U.S. predominance seemed to redefine America’s role in the world. President George H. W. Bush talked about a “new world order.” But its characteristics were unclear. Bush’s first major foreign policy action seemed a return to U.S. interventionism in the Western Hemisphere. In 1989, Bush sent troops to Panama to overthrow the government of Manuel Antonio Noriega, a 2 former U.S. ally who became involved in the international drug trade. Though it cost more than 3,000 Panamanian lives and was condemned by the United Nations as a violation of international law, Bush called it a great success. The United States installed a new government and tried Noriega in the American courts. A deeper crisis emerged in 1990 when Iraq invaded and annexed Kuwait, an oil-rich sheikdom on the Persian Gulf. Afraid that Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein might invade Saudi Arabia, a longtime U.S. ally that supplied more oil to the United States than any other nation, Bush sent troops to defend that country and warned Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait or face war. The policy caused intense debate. Critics argued that diplomacy was still possible, and that neither Kuwait nor Saudi Arabia were free or democratic nations. But Iraq’s invasion so blatantly violated international law that Bush assembled a large coalition of nations to wage the war, won UN support and sent half a million US troops and the navy to the region. In early 1991, U.S. forces drove the Iraqi army from Kuwait. Tens of thousands and 184 Americans died in the conflict. The United Nations ordered Iraq to disarm and imposed economic sanctions that caused widespread civilian suffering for the rest of the 1990s, but Hussein retained power. A large U.S. military establishment stayed in Saudi Arabia, angering Islamic fundamentalists who thought the U.S. presence insulted Islam. But the U.S. military won quickly and avoided a Vietnam-style war. President Bush soon defined the Gulf War as the first struggle to create a world of democracy and free trade. General Colin Powell, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Dick Cheney, the secretary of defense, offered two different policy directions. Powell argued that the post–Cold War world would see conflicts in unexpected places, and that the United States, to avoid becoming the world’s policeman, should not send troops without clear objectives and withdrawal plans. Cheney argued that with the end of the Soviet Union, the United States had the power to reshape the world and prevent hostile states from assuming regional power. Cheney argued that the United States had to use force, without world support, if necessary, to maintain strategic dominance. In 1991, the economy slipped into a recession. Unemployment jumped and family income stagnated. Widespread unease about America’s future gripped the public, and Bill Clinton, the former governor of Arkansas, seized the Democratic nomination the next year by advocating both social liberalism (support for gay rights, abortion rights, affirmative action) and conservatism (opposition to bureaucracy and welfare). Very charismatic, Clinton seemed interested in voters’ economic fears, and he blamed rising inequalities and job loss on deindustrialization. Bush, by contrast, seemed unaware of ordinary Americans’ lives and problems. Republican attacks on gays, feminists, and abortion rights also alienated voters. A third candidate, Ross Perot, an eccentric Texas billionaire, also ran for president, attacking Bush and Clinton for not having the economic skills to combat the recession and the national debt. Enjoying much support at first, Perot’s candidacy waned. But he received 19 percent of the popular vote. Clinton won by a substantial margin, humiliating the only recently very popular Bush. 3 Clinton at first seemed to repudiate the policies of Reagan and Bush. He appointed several women and blacks to his cabinet, and named supporters of abortion rights to the Supreme Court. His first budget raised taxes on the wealthy and expanded tax credits for low-income workers, which raised more than 4 million Americans out of poverty. But Clinton shared with his predecessors a passion for free trade. Despite strong opposition from unions and environmentalists, he had Congress in 1993 pass the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which created a free-trade zone out encompassing Canada, the United States, and Mexico. The major policy initiative of Clinton’s first term, however, was the attempt with his wife, Hilary, to address the rising cost of health care and the increasing number of Americans who lacked health insurance. In Canada and western Europe, governments provided universal medical coverage. Yet the United States, with the world’s most advanced medical technology, had a very incomplete health insurance system. The Great Society had given coverage to the elderly and poor in Medicare and Medicaid, and many employers offered health insurance to their workers. But tens of millions of Americans had no coverage, and in the 1980s, businesses started to move employees from individual doctors to health maintenance organizations (HMOs), which critics charged denied procedures to patients. Clinton’s plan would have provided universal coverage through large groups of HMOs, but doctors and insurance and drug companies attacked it fiercely, fearing government regulations that would limit their profits. Too complex and seeming to expand unpopular federal bureaucracy, the plan expired in 1994. By 2008, some 50 million Americans, most of whom had full-time jobs, lacked health insurance. A slow economic recovery and few accomplishments in Clinton’s first two years turned voters against him. In the 1994 elections, Republicans won control of both houses of Congress, the first time since the 1950s. They called their victory the “Freedom Revolution.” Newt Gingrich, a conservative Georgia congressman who became Speaker of the House, led the campaign. Gingrich devised a platform called the “Contract with America,” promising to reduce government, taxes, and economic and environmental regulations, overhaul welfare, and end affirmative action. Republicans moved quickly to implement the contract’s provisions. The House deeply cut social, educational, and environmental programs, including the popular Medicare system. But with the president and Congress unable to compromise, the government shut down all nonessential operations in late 1995. It became clear that most voters had not voted for the Republicans and Gingrich’s Contract with America, but against Clinton, and Gingrich’s popularity dropped. Clinton rebuilt his popularity by campaigning against a radical Congress. He opposed the most extreme parts of the Republican program, but embraced others. In early 1996, he declared that the era of “big government” was over, repudiating Democratic Party liberalism and embracing the anti-government attitude of conservatives. He approved acts to deregulate broadcasting and telephone companies. In 1996, over Democratic protests, he also abolished Aid to Dependent 4 Families with Children, commonly known as “welfare.” At that time, 14 million Americans, including 9 million children, received AFDC assistance. Stringent new eligibility requirements at the state level and economic growth reduced welfare rolls, but the number of children in poverty stayed the same. Clinton’s strategy, called “triangulation,” was to embrace the most popular Republican polices while rejecting positions unpopular among the suburban middle class. Clinton thus neutralized Republican charges that the Democrats wanted to raise taxes and assist the idle. Clinton’s passion for free trade alienated many working-class Democrats but convinced middle-class voters that the Democrats were not dominated by unions. In 1996, Clinton, who had consolidated the conservative shift away from Democratic liberalism, easily defeated Republican Bob Dole in the presidential elections. Like Carter, Clinton was most interested in domestic affairs and took steps to settle persistent international conflicts and promote human rights. He was only partly successful. He strongly supported the 1993 Oslo Accords, in which Israel recognized the Palestine Liberation Organization and a plan for peace was outlined. But neither side fully implemented the accords. Israel continued to build Jewish settlements on Palestinian land in the West Bank, a part of Jordan that Israel had occupied since the 1967 Six-Day War. The new Palestinian Authority, which shared in governing parts of the West Bank on the way to full statehood, was corrupt, powerless, and unable to check groups that attacked Israel. At the end of his presidency, Clinton brought leaders from the two sides to Camp David to try to work out a final peace treaty, but the meeting failed and violence resumed. Like Carter, Clinton found it difficult to balance concern for human rights with U.S. strategic and economic interests and to form guidelines of humanitarian intervention overseas. The United States did nothing when tribal massacres in Rwanda killed more than 800,000 people and created 2 million refugees. Clinton also faced crisis in Yugoslavia, a multi-ethnic state that started to disintegrate in the 1990s, after its communist government collapsed in 1989. In a few years, five new states emerged in the country, and ethnic violence plagued several of these new nations. In 1992, Serbs in Bosnia, which was on the historic boundary between Christianity and Islam in southeastern Europe, started a war to drive out Muslims and Croats. They used mass murder and rape as military strategies, which came to be known as “ethnic cleansing”— – the forcible expulsion from an area of a particular ethnic group. More than 100,000 Bosnians, mostly civilians, had been killed by the end of 1993. After long inaction, The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) launched air strikes against Bosnian Serb troops, and UN troops, including 20,000 Americans, arrived as peacekeepers. In 1998, when Yugoslavian troops and local Serbs started to revive ethnic cleansing, this time against Albanians in Kosovo, a Serbian province, nearly a million Albanians fled. NATO launched a two-month war in 1999 that led to the deployment of U.S. and UN troops in Kosovo. Human rights became more prominent in international affairs during Clinton’s presidency. They emerged as a justification for intervention in matters once 5 considered to be the internal affairs of sovereign nations, and the United States dispatched troops around the world for humanitarian reasons to protect civilians. New institutions including courts developed to prosecute human rights violators, such as tribunals and war crimes courts regarding Rwanda and Slobodan Milesovic, Yugoslavia’s president. Spanish and British courts even nearly charged Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet with murder, but he was too ill to stand trial. Clinton’s popularity greatly rested on America’s remarkable economic expansion in the mid- and late 1990s after an earlier recession. Unemployment returned to the low levels of the 1960s, and inflation did not rise, in part due to increasing oil production and weak unions and global competition that that made it difficult to raise wages and prices. The boom was the longest uninterrupted economic expansion in U.S. history. Because Reagan and Bush left behind enormous deficits, Clinton tried hard to balance the budget, and economic growth actually produced so much government revenue that Clinton in his second term balanced the budget and actually produced budget surpluses. Many in the 1990s hailed the birth of a “new economy” in which computers and the Internet would create enormous new efficiencies and the production and sale of information would replace manufacturing as the center of the U.S. economy. Computers, first developed after World War II, improved remarkably in the 1960s and 1970s, especially because of miniaturization of parts through the microchip. Microchips made possible a wave of new consumer products in the 1980s and 1990s, including video cassette recorders, handheld video games, cellular phones, and digital cameras. Beginning in the 1980s, companies like Apple and IBM sold computers for business and home use, and soon computers were used in all kinds of workplaces. They also changed private life, and centers of computer technology produced local economic booms. The Internet, first developed as a high-speed military communications network, was simplified and opened to commercial and individual use through personal computers. The Internet expanded the flow of information and communications more radically than any invention since the printing press and democratized information when the ownership of newspapers, television stations, and publishing was being concentrated into fewer and fewer hands. Elsewhere in the world, economic crisis loomed. In western Europe, unemployment stayed far higher than in the United States. Japan was mired in a long-term recession. Despite western loans and investment, Russia moved from one crisis to another. President Boris Yeltsin, relying on U.S. free market economists and the Clinton administration, used “shock therapy” that privatized state-owned enterprise and imposed severe cuts in wages and in guaranteed jobs, health care, and housing. Foreign investors and a new Russian business class reaped fabulous profits, while most of the population dropped into poverty. Many Third World nations faced large trade deficits and problems repaying loans from foreign banks and other institutions. A fiscal crisis rocked Asian governments that were rescued only by massive loans from the International Monetary Fund. Such bailouts caused 6 criticisms that globalization increased social inequalities. Foreign investors had loans repaid, but nations were required to balance budgets by cutting public spending, which disproportionately hurt the poor. Economic growth and the new economy idea in the United States sparked a frenzied stock market boom. Large and small investors poured funds into stocks, driven by new firms charging lower fees. By 2000, most U.S. households owned stocks either directly or through investments in mutual funds and pension and retirement accounts. Investors heavily put funds into new “dot coms”—companies that did business on the Internet and symbolized the new economy. Stocks for these kinds of companies skyrocketed, even if many never turned a profit. But journalists and stock brokers argued that this new economy had so changed business that traditional methods could not be used to assess a company’s value. Inevitably, this bubble burst. On April 14, 2000, stocks suffered their largest one-day drop in history. For the first time since the Depression, stock prices declined for three years straight (2000–2002), making billions of dollars in Americans’ net worth and pensions funds disappear. Only in 2006 did the stock market reach levels of early 2000. By 2001, the U.S. economy had fallen into recession. After the stock market dropped, it became clear that part of the stock boom of the 1990s was fueled by fraud. In 2001 and 2002, Americans saw almost daily revelations of extraordinary greed and corruption on the part of brokerage firms, accountants, and corporate executives. In the late 1990s, accounting firms like Arthur Anderson, huge banks like J.P. Morgan Chase and Citigroup, and corporate lawyers reaped huge fees from complex schemes to push up companies’ stock prices by hiding their true financial condition. Enron, a Houston-based energy company that bought and sold electricity rather than producing it, reported billions of dollars in losses as profits. Wall Street brokers urged clients to sell risky stocks and pushed them on unknowing customers. Insiders jumped ship when stock prices fell, and individual investors were left with worthless shares. Several corporate criminals went to jail after highly publicized trials, and even reputable firms like J.P. Morgan Chase and Citigroup agreed to pay billions of dollars to compensate investors on whom they had pushed worthless stocks. At the height of the 1990s boom, free trade and deregulation seemed the right economic model. But the retreat from government economic regulations, embraced both by the Republican Congress and President Clinton, left no one to represent the public interest. The sectors most affected by the scandals, such as energy, telecommunications, and stock trading, had all been deregulated. Many stock frauds, for example, stemmed from the repeal in 1999 of the Glass-Steagall Act, a New Deal law that separated commercial banks, which accepted deposits and made loans, from investment banks, which invested in stocks and real estate and took larger risks. This repeal created “superbanks” with both functions. These banks engaged in huge risks, knowing that the federal government would have to bail them out if they failed. Conflicts of interest were everywhere. Banks financed new stocks offered by new Internet firms while their investment arms sold the shares to the public. These 7 banks also poured money into risky mortgages. When the housing bubble collapsed in 2007–2008, the banks suffered losses that threatened the entire financial system. The Bush and Obama administrations felt they had no choice but to spend billions of dollars in taxpayer money to save the banks from their own misconduct. The boom the began in 1995 benefited most Americans. For the first time since the early 1970s, average real wages and family incomes began to rise significantly. With low unemployment, economic expansion hiked wages for families at all income levels, even aiding low-skilled workers. Yet, average wages for non-supervisory workers, after inflation, stayed below 1970s levels. Overall, in the last two decades of the twentieth century, the poor and middle class became worse off while the wealthy became significantly richer. The wealth of the richest Americans exploded in the 1990s. Bill Gates, head of Microsoft and the nation’s richest person, owned as much wealth as the bottom 40 percent of the U.S. population put together. In 1965,the salary of the typical corporate chief executive officer was only 26 times that of the average worker; in 2000, it was 310 times higher. Companies continued to shift manufacturing overseas. Because of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), many factories moved to Mexico, where, just across the border, U.S. firms enjoyed cheaper labor and weak environmental and safety regulations. Despite low unemployment, companies’ threats to shut down and move exerted downward pressure on wages. By 2000, the United States no longer led the world in hourly wages of factory workers and had become the most unequal society in the developed world. High-tech firms did not create enough jobs to compensate for the loss of manufacturing, and large employers, the largest of which was Wal-Mart, a giant discount retail chain, paid very low wages. Wal-Mart also prevented workers from joining unions. In 2000, more than half of the labor force worked for less than $14 per hour, and because of the decline of labor unions, fewer workers had benefits common to union contracts, such as health insurance. Although the Cold War’s end raised hopes for an era of global harmony, the world instead saw renewed emphasis on group identity and demands for group recognition and power. While nationalism and socialism had united peoples of different backgrounds in the nineteenth century, now ethnic and religious antagonisms sparked conflict in Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and parts of Europe. In part a reaction to the globalization of a secular culture based on consumption and mass entertainment, intense religious movements flourished—Hindu nationalism in India, orthodox Judaism in Israel, Islamic fundamentalism in much of the Muslim world, and evangelical Christianity in America. The United States, to a lesser degree, experienced divisions from the intensification of ethnic and racial identities and religious fundamentalism. Shifts in immigration made cultural and racial diversity more visible in the United States. Until the immigration law of 1965, most immigrants came from Europe, but after 1965, the sources of immigration changed dramatically. Between 1965 and 2000, about 24 million immigrants entered the United States. About 50 percent 8 came from Latin America and the Caribbean, 35 percent came from Asia, and smaller numbers came from the Middle East and Africa. Only 10 percent came from Europe, mostly from the Balkans and the former Soviet Union. In 2000, 33 million— 11 percent of the U.S. population—was foreign born. This influx of immigrants changed the country’s religious and racial map. By 2000, more than 3 million Muslims lived in the United States, and the combined population of Buddhists and Hindus exceeded 1 million. As in the past, most immigrants settled in urban areas, but unlike the past, many immigrants quickly moved into outlying neighborhoods and suburbs. While most immigrants stayed on the East and West Coasts, some moved to other parts of the country, bringing cultural and racial diversity to previously homogeneous communities in the American heartland. The new immigration was part of globalization’s uprooting of labor worldwide. Migrants to the United States came from diverse backgrounds. They were poor refugees from economic and political crisis, as well as educated professionals seeking skilled work in America. For the first time in U.S. history, most immigrants were women and took jobs in the service and retail sectors. With cheap global communications and air travel, immigrants retained strong ties with their countries of origin. Latinos were the largest single new immigrant group. The term was invented in the United States and described people from Mexico, South and Central America, and Spanish-speaking islands of the Caribbean. By 2000, Mexico, with 95 million people, had become the largest Spanish-speaking nation, and its poverty, high birthrate, and proximity to the United States made it a source of massive legal and illegal immigration. More than 45 million in 2007, Latinos became the largest minority group in the United States, and Latinos were highly visible in entertainment, sports, and politics. But Latino communities stayed much poorer than the rest of the country. Most immigrants from Mexico and Central America competed at the lowest levels of the job market, and many legal and illegal immigrants worked in low-wage urban or agricultural jobs. Asian-Americans also became more visible in the 1990s. While there had long been a small population of Asian descent in California and New York City, immigration from Asia swelled after 1965. By 2000, there were 11.9 million Asian Americans, eight times the figure of 1970. Asians were highly diverse in origin, and included the well-educated from Korea, India, and Japan, as well as poor immigrants from Cambodia, Vietnam, and China. Once subject to discrimination, Asian-Americans now achieved success, particularly in higher education, contributing to whites’ characterization of them as a “model minority.” But Asian-Americans showed increasing income and wealth gaps within their communities. The growing visibility of Latinos and Asians suggested that a two-race, black and white racial system no longer described American life. Multiracial imagery filled television, films, and ads, and inter-racial marriage became more common and acceptable. Some hailed the “end of racism,” but others argued that while Asians and Latinos were becoming absorbed into “white” America, the black-white divide 9 remained. In 2000, it was clear that diversity was permanent and that whites would make up a smaller and smaller percentage of the population in years to come. Compared with earlier in the century, the most dramatic change in American life in 2000 was the absence of legal segregation and the presence of blacks in areas of American life from which they had once been excluded. Declining overt discrimination and affirmative action helped introduce blacks in unprecedented numbers into U.S. workplaces. Economic growth in the 1990s also raised the average income of black families significantly. Another significant change in black life was the higher visibility of Africans in the immigrant population. Between 1970 and 2000, twice as many Africans immigrated to the United States had entered during the entire period of the slave trade, and all the elements of the African diaspora—from natives of Africa, Caribbeans, Central and South Americans of African descent, and Europeans with African roots—could be found in the United States. While some were refugees, many others were highly educated Africans, and some African nations complained of “brain drain” as highly skilled Africans sought work in the United States. Yet most African-Americans were worse off than whites or many recent immigrants. The black unemployment rate remained double that of whites, and in 2007 their median family income and poverty rate put them behind whites, Asians, and Latinos. Blacks continued to lag in every index of social sellbeing from health to housing quality, and despite a growing black middle class, far fewer blacks owned homes or held professional or managerial jobs than whites. Gaps in wealth between blacks and whites remained enormous. The Supreme Court gradually retreated from the civil rights revolution, and made it more difficult for victims of discrimination to win lawsuits and proved more sympathetic to whites’ claims that affirmative action had discriminated against them. And despite growing racial diversity, school segregation, now based in residential patterns and the divide between urban and suburban school districts, rose, with urban schools overwhelmingly having minority student bodies. By 2000, nearly 80 percent of white students attended schools, where they met few if any pupils of another race. School funding rested on property taxes, and poor communities continued to have less to spend on education than wealthy ones. In the 1960s, the U.S. prison population declined, but in the next decade, with urban crime rates rising, politicians of both parties tried to portray themselves as “tough on crime.” They wanted long prison sentences rather than rehabilitation, and treated drug addiction as a crime rather than a disease. State governments greatly increased penalties for crime and reduced parole. Successive presidents launched “wars” on the use of drugs. The number of Americans in prison rose dramatically, most of them incarcerated for non-violent drug offenses. In the 1990s, with the end of the “crack” epidemic and more effective policing, crime rates dropped dramatically across the country. Yet because of sentencing laws, the prison population still rose, and by 2008, 2.3 million were in prison, and several million more were on parole, probation, or under some form of criminal supervision. No other Western society came close to these numbers. A “prison-industrial complex” developed, in which communities suffering from deindustrialization built prisons to 10 create jobs and income. Convict labor, a practice curtailed by the labor movement in the late nineteenth century, was revived, with private companies “leasing” prisoners for low wages. Racial minorities were most affected by this paradox of islands of unfreedom in a nation of liberty. In 1950, whites had been 70 percent of the nation’s prison population, and non-whites, 30 percent. By 2000, these figures were reversed. Severe penalties for crack convictions, concentrated in urban areas, contributed to this trend. The percentage of blacks in prison was eight times higher than for whites. More than one-quarter of all black men could expect to serve some prison time in their lifetime. Former prisoners found it hard to find work, and in some southern and western states were disenfranchised, contributing to blacks’ economic and political disempowerment. Blacks were also more likely than whites to receive the death penalty. The Supreme Court had suspended capital punishment in 1972, but soon let it resume. By 2000, the United States ranked with China, Iran, and Saudi Arabia in the number of prisoners on death row. Urban blacks’ frustration exploded in 1992 when an all-white suburban jury found four Los Angeles police officers not guilty in the beating of black motorist Rodney King (even though the assault had been videotaped). The deadliest urban uprising since the 1863 draft riots unfolded, with fifty-two deaths and nearly $1 billion in property damage. Many Latinos, sharing blacks’ frustrations, joined them. This event suggested that despite the civil rights revolution, the nation had not addressed the plight of the urban poor. The rights revolution persisted in the 1990s, especially in new movements for recognition. In 1990, disabled Americans won passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, which banned discrimination in hiring and promotion against persons with disabilities and required accommodations for them in public buildings. Gay groups played a greater role in politics, and campaigns for gay rights became more visible, especially as more people became infected by acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), a fatal disease spread by sexual contact, drug use, and blood transfusions, that first emerged in the early 1980s and quickly became an epidemic among gay men. A movement emerged to promote “safe sex,” stop discrimination against those with AIDS, and press the federal government to combat the disease. By 2000, fewer Americans were contracting AIDS, although it became a massive epidemic elsewhere, such as Africa. Efforts by American Indians to claim their rights continued in the 1990s as well. In the 2000 census, the Indian population reached 4 million, a sign of growth and a renewed sense of pride, as more people self-identified as native American. More tribes fought and won campaigns for financial restitution for past injustices. In some cases, Indians are still American citizens who enjoy a king of quasi-sovereignty. Some tribes now operate casinos in states that otherwise ban them; the Pequot tribe, nearly exterminated by the Puritans in 1637, now operate Foxwoods, the world’s largest casino. Yet many native Americans continue to live in poverty, and 11 most of those living on reservations continue to be among the poorest people in the nation. One of the most striking developments of the 1990s was the celebration of group difference and demands for group recognition. “Multiculturalism” came to denote new awareness about a diverse American past and demands that jobs, education, and politics reflect that diversity. As more female and minority students attended colleges and universities, these institutions tried to diversify their faculties and revise their curriculum. Academic programs dealing with specific groups, such as Women’s Studies, Black Studies, and Latino Studies, proliferated, and many scholars now stressed the experiences of diverse groups of Americans. Public opinion polls showed increasing toleration for gays and interracial dating. Some Americans were alarmed by the higher visibility of immigrants, racial minorities, and the continuing sexual revolution, fearing cultural fragmentation and moral anarchy. Conservatives and some liberals attacked “identity politics” and multiculturalism for undermining traditional nationhood. The definition of American nationality became a contentious question once more. Republicans appealed to those alarmed by non-white immigrants and the decline of traditional “family values,” but differences over diversity crossed party lines. Harsh debates unfolded over whether immigrant children should be required to learn English and immigration should be checked. By 2000 nearly half of all states had made English their official language. And some aspects of social welfare were barred from immigrants who had not yet become citizens. Yet overall, in this period the United States became a more tolerant society, and bigoted politics often backfired. In 2000, Republican presidential candidate George W. Bush promoted a multicultural, not exclusionary, conservatism. Immigration was one front in what became called the Culture Wars—battles over moral values in the 1990s. The Christian Coalition, founded by evangelical minister Pat Robertson, became a major force in Republican politics, launching crusades against gay rights, secularism in public schools, and government aid to the arts. Sometimes it seemed the nation was refighting older conflicts between traditional religion and modern secular culture. Some local governments required the teaching of creationism as an alternative to Darwin’s theory of evolution. And conservatives continued to assail the alleged effects of the 1960s, including the erosion of the nuclear family, the changing racial landscape caused by immigration, and a decline in traditional values. The 2000 census showed “family values” were indeed changing. Half of all marriages ended in divorce and over a third of all births were to unmarried women, including more professional women in their 30s and 40s. Two-thirds of married women worked outside of the home, and less than one-fourth of all households were “traditional,” with a wife, husband, and their children. Yet the pay gap between men and women persisted. In 1994, the Supreme Court reaffirmed a woman’s right to obtain an abortion. But the narrow vote indicated that the legal status of abortion rights could change, given future court appointments. By 2000, conservatives had 12 not been able to eliminate abortion rights, restore prayer in public schools, or persuade women to stay at home. More women than ever attended college and entered professions such as law, medicine, and business. Some radical conservatives who believed the federal government was threatening American freedom started to arm themselves and form private militias. Fringe groups spread a mixture of radical Christian, racist, anti-Semitic, and antigovernment ideas. Private armies vowed to resist enforcement of federal gun control laws, and for millions of Americans, gun ownership became the highest symbol of liberty. Militia groups used the symbolism and language of the American Revolution, and warned that leaders of both political parties were conspiring to surrender U.S. sovereignty to the United Nations or another shadowy international conspiracy. Such groups gained attention when Timothy McVeigh, a member of the militant anti-government movement, exploded a bomb at a federal office building in Oklahoma City that killed 168 persons. McVeigh was capture, convicted, and executed. The intense partisanship of the 1990s, strange because of Clinton’s centrism, seemed to emerge from Republicans’ feelings that Clinton symbolized everything conservatives disliked about the 1960s. Clinton had smoked marijuana and participated in antiwar protests as a college student, married a feminist, led a multicultural administration, and supported gay rights. Clinton’s opponents and the media waited for opportunities to assail him, and he provided them. In the 1980s and 1990s, the scrutiny of public officials’ private lives intensified. From the day Clinton took office, charges of misconduct dogged him. In 1993, an investigation began into an Arkansas real estate deal known as Whitewater, from which Clinton and his wife profited. The next year, an Arkansas woman, Paula Jones, filed a suit charging that Clinton had sexually harassed her while governor. In 1998, it became known that Clinton had had an affair with Monica Lewinsky, a White House intern. Kenneth Starr, the special counsel appointed to investigate Whitewater, turned to Lewinsky. He issued a long report with lurid details about Clinton’s acts with the young woman and accused Clinton of lying when he denied the affair in a deposition. In December 1998, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives voted to impeach Clinton for perjury and obstruction of justice, and he became only the second president to be tried for impeachment before the Senate. But in the Senate, neither charge garnered even a simple majority, much less than the two-thirds needed to remove him from office. Although Andrew Johnson’s impeachment in 1868 had revolved around momentous questions of Reconstruction, Clinton’s impeachment seemed based in what many saw as a juvenile escapade. Clinton stayed remarkably popular throughout the proceedings. Clinton might have won a third term in office if he had been able to run, but after FDR’s presidency, the Constitution was amended to limit presidents to two terms in office. Democrats nominated vice-president Al Gore to succeed Clinton. Republicans chose George W. Bush, the governor of Texas and son of Clinton’s predecessor, as their candidate and former defense secretary Dick Cheney as his running mate. 13 The election was one of the closest in U.S. history, and its outcome was uncertain until after a month after the vote. Gore won the popular vote by a tiny margin of 540,000 of 100 million votes cast: .5 percent. Victory in the electoral college hinged on who carried Florida, and there, amid widespread confusion at polls and claims of irregularities in counting the ballots, Bush claimed a margin of a few hundred votes. Democrats demanded a recount, and the Florida Supreme Court ordered it. It fell to the Supreme Court to decide the outcome, and on December 12, 2000, by a 5–4 vote, the Court ordered a halt to the Florida recount and allowed the state’s governor, Jeb Bush (George W. Bush’s brother), to certify that Bush had won the state and therefore the presidency. The decision in Bush v. Gore was one of the strangest in the Supreme Court’s history. In the late 1990s, the Court had reasserted the powers of states in the federal system, reinforcing their immunity from lawsuits by individuals who claimed to suffer from discrimination, and denying the power of Congress to force states to carry out federal policies. Now, the Court overturned a decision of the Florida Supreme Court that interpreted the state’s election laws. Many people did not think the Supreme Court would take the case since it did not seem to raise a federal constitutional question. But the justices argued that the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause required that all ballots in a state be counted by a single standard, something impossible in Florida’s patchwork election system. The 2000 decision was most remarkable for how it revealed divisions in the country. Bush and Gore each received essentially half of the popular vote. The final count in the electoral college was 271–266, the narrowest margin since 1876. The Senate was split 50–50 between the two parties. These figures concealed deep political and social fissures. Bush carried the entire South and nearly all the states of the trans-Mississippi farm belt and Rockies. Gore won almost all the states of the Northeast, Old Northwest, and West Coast. Urban-area residents voted mostly for Gore, rural-area voters for Bush. Racial minorities mostly supported Gore, while whites preferred Bush. Women favored Gore, while men favored Bush. Democrats blamed the Supreme Court, Ralph Nader, and bad luck for Bush’s victory. Nader, the candidate of the environmentalist Green Party, had won tens of thousands of votes in Florida that otherwise might have gone to Gore. But the largest reason Gore lost Florida was that 600,000 persons, mostly black and Latino men, had been disenfranchised for life after being convicted of a felony. The 2000 elections revealed a political democracy in trouble. The electoral college, designed by the nation’s founders to enable the nation’s prominent men rather than ordinary voters to select the president, gave the White House to voters who did not receive the most votes. A nation priding itself on modern technology had voting system of computers in which citizens’ choices could not be reliably determined. Both presidential and Congressional campaigns cost more than $1.5 billion, mostly raised from wealthy individuals and corporate donors, and this reinforced the popular belief that money dominated politics. There were signs of a widespread 14 disengagement from public life. As governments at all levels turned their activities over to private contractors, and millions of Americans lived in homogenous gated communities, the idea of a shared public sphere seemed to disappear. Voluntary groups like the Boy Scouts and the Red Cross all saw less members and volunteers. Voter turnout remained much lower than in other democracies; nearly half of eligible voters did not go to the polls, and fewer voted in state and local elections. Candidates sought to occupy the center, used polls and media consultants to shape their messages, and steered clear of difficult issues like health care, race, and economic inequality. The twentieth century had seen both much human progress and tragedy. Asia and Africa had decolonized, women had gained full citizenship in most of the world, and science, medicine, and technology greatly advanced. New products at cheaper prices improved daily life for humans more than in any other century in history. Worldwide life expectancy jumped by more than twenty-five years, and illiteracy dropped significantly. For the first time in world history, most of mankind pursued primary economic activities beyond simply securing food, clothing, and shelter. But the twentieth century also saw the deaths of millions in wars and genocides and widespread degradation of the natural environment. In the United States, people lived longer and healthier lives compared to previous generations and enjoyed material comforts unimaginable 100 years before. Yet poverty, income inequality, and infant mortality were higher in the United States than in other industrialized nations, and fewer than 10 percent of private sector workers belonged to unions. While many changes in American life, such as new roles for women, suburbanization, and deindustrialization have occurred elsewhere, the United States was quite different from other nations at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Here ideas of freedom seemed more associated with individual freedom than social welfare. Fewer Americans than Europeans thought eliminating want was an important social goal, and more Americans were religious. America seemed exceptional in other ways too. The United States had the highest murder rate using guns. It also lagged behind other nations in providing social rights to citizens. Europe’s governments guarantee paid vacations and sick days each year for workers, while U.S. employers are required to offer neither. The United States is one of only four nations in the world that do not require paid maternity leave for a woman after she gives birth. In a speech on January 1, 2000 (a year before the twenty-first century actually began), President Clinton declared that “the great story of the twentieth century is the triumph of freedom and free people.” Freedom was a central point of selfdefinition for individuals and the society. Americans cherished freedom and were more tolerant of cultural differences, and enjoyed freedoms of expression unmatched anywhere. But their definition of freedom had changed over the century. The rights revolution and anti-government sentiment had defined as freedom the ability of the individual to realize their potential and desires free from authority. Other American ideals of freedom, defined as economic security, active participation 15 in government, or social justice for the disadvantaged, seemed in retreat. Americans appeared to seek freedom within themselves, not through social institutions or public engagement. And Americans seemed to have less “industrial freedom” than before. Economic inequalities and globalization seemed to make individual and even national sovereignty meaningless, and this seemed to endanger the economic security and rights that had traditionally linked democratic participation and membership to the nation-state. 16