Mongolia Journal - University of Missouri

advertisement

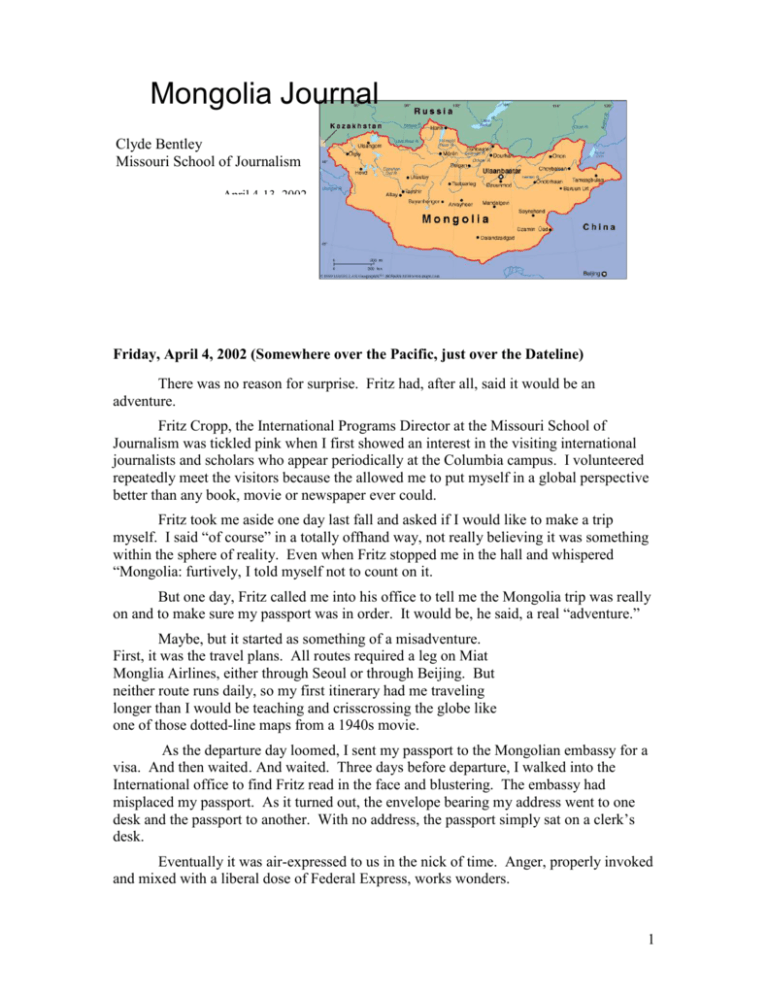

Mongolia Journal Clyde Bentley Missouri School of Journalism April 4-13, 2002 Friday, April 4, 2002 (Somewhere over the Pacific, just over the Dateline) There was no reason for surprise. Fritz had, after all, said it would be an adventure. Fritz Cropp, the International Programs Director at the Missouri School of Journalism was tickled pink when I first showed an interest in the visiting international journalists and scholars who appear periodically at the Columbia campus. I volunteered repeatedly meet the visitors because the allowed me to put myself in a global perspective better than any book, movie or newspaper ever could. Fritz took me aside one day last fall and asked if I would like to make a trip myself. I said “of course” in a totally offhand way, not really believing it was something within the sphere of reality. Even when Fritz stopped me in the hall and whispered “Mongolia: furtively, I told myself not to count on it. But one day, Fritz called me into his office to tell me the Mongolia trip was really on and to make sure my passport was in order. It would be, he said, a real “adventure.” Maybe, but it started as something of a misadventure. First, it was the travel plans. All routes required a leg on Miat Monglia Airlines, either through Seoul or through Beijing. But neither route runs daily, so my first itinerary had me traveling longer than I would be teaching and crisscrossing the globe like one of those dotted-line maps from a 1940s movie. As the departure day loomed, I sent my passport to the Mongolian embassy for a visa. And then waited . And waited. Three days before departure, I walked into the International office to find Fritz read in the face and blustering. The embassy had misplaced my passport. As it turned out, the envelope bearing my address went to one desk and the passport to another. With no address, the passport simply sat on a clerk’s desk. Eventually it was air-expressed to us in the nick of time. Anger, properly invoked and mixed with a liberal dose of Federal Express, works wonders. 1 The most unfortunate part of this adventure for me was when we realized Cecile’s business trip to the west coast would put here in Olympia, Washington, the day I left. The good part of that was she got to spend Easter with Gillian and Will. Gillian, our daughter, is pregnant with our first grandchild and needed a visit from Mom worse than I needed her sane and capable guidance as I prepared for the trip. The night before departure I had planned to pack leisurely and go to bed early so I could rise at 4 a.m. to catch the plane. Cecile had drafted a checklist for me, but I did not find it on the seat of the chair I had been sitting until it was well after 11 p.m. I’m an organizational schizophrenic. There are certain times – like when I oversee a project or set up my workshop – when I am absolutely anal. But in everyday life and in events that often matter, I putter and dither and re-do the same task a halfdozen times. About 11 p.m., I got a call from the Mongolian student who volunteered to translate my materials. She had been called away to help a friend all day, but tried to get in touch with me earlier. I had e-mailed her, but her Hotmail box was full. Nevertheless, she quickly translated my business card and e-mailed it to me so I could put the Mongolian text onto mailing labels and then stick them to the back of my cards. It was nearly 2 a.m. when I got to bed. And I later realized the computer diskettes I had carefully labeled for the trip were still sitting on my office desk and that both the phone modem cord and Ethernet cord for my computer were lying on the home office floor. Then just before I packed the computer, I received my first e-mail from the Mongolian technician assigned to me. She said she was glad to get my teaching schedule, but made no mention of the four sets of presentation slides I sent earlier for translation. And, she added, some of the people attending would be very grateful if I concentrated on technology issues. Great. All my presentation materials were on content and organizational issues. Not to worry. Garrett got up with me and we were out the door (sleepy, but at least marginally awake), by 4:30 a.m. We had never been to the Columbia Regional Airport and so we had to jointly decipher the map to see how to get there. I need not have worried. At the appointed one hour before departure, I was in the terminal but the airline people were not. They finally showed up to check the bags of the six or seven travelers at about 5:20 a.m. The nice woman at the counter took my tickets, punched numbers into the computer and generated a long paper baggage tag. “Enjoy Korea, “ she said. I blanched. No matter what sequence of keys she or her supervisor hit, no one could get my bags checked to Ulaanbaatar. Finally, they gave up and asked me to try checking the bag in St. Louis. St. Louis, however, had no better ticket magicians. They finally decided that American Airlines had no baggage forwarding agreement with Miat Mongolia. Instead, I would have to pick up my bags in San Francisco and see if Singapore Airline had better luck. St. Louis to San Francisco was not at all memorable, largely because I slept all 2 but the few minutes it took to wolf down the airline muffin that served as breakfast. San Francisco International is a pretty airport, but something of a maze. I rolled my big red suitcase through several store-studded terminals before finding the hall of international airlines. It was a fun place, with people of every national costume and dialect jostling to get to the appropriate ticket counter. The four clerks at Singapore Airlines seemed overjoyed to see me. I was their only customer in an otherwise busy terminal. The worked their computer magic in both English and Chinese, but finally the senior clerk came to me apologetically to say the Seoul airport was allowing no “check through” of baggage. My plane from San Francisco was due to land in Seoul about an hour before my plane to Mongolia departed, so my heart took another spring for my throat. But what could I do but check my bag to Seoul. In the gate area, I marveled at the beautiful Singapore Airlines flight crew. The male stewards wore snappy blue blazers (light for junior, dark for senior) and sported matching church-camp haircuts. The female stewardesses (that’s what the brochure called them) work stunning sarong-like dresses that were also color coded for rank. The pilots all looked like they had just picked up their uniforms at the cleaners. I was a bit surprised to hear myself paged, but I had just unsuccessfully tried to call Cecile and I thought she might be trying to get back to me. Instead, a petite but steely-eyed Asian woman in the darkest blazer yet asked if she could please see my passport and ticket. I thought I was being kicked off the plane, but she just flashed a momentary smile and told me that SHE would get my bag checked. She talked sharply on the radio to someone in the ground crew and told me someone would tell me of her success on the plane. I was buoyed, but needlessly so. The moved me to the front of the plane so I could get off earlier, and then a hulk of a steward came to tell me how sorry he was, but I would have to pick up my bag in Seoul. I think he felt worse about it than I did. That said, he went forward to talk to the captain, who sent a message to me that we would arrive with nearly the full hour to get my bags and that he would radio ahead to warn Miat Mongolia that I was running a tight schedule. Singapore Airline is amazing. Before we took off, one of those pretty ladies in a sarong brought me a hot, moist towel to sooth my face. If I had not said “enough,” they would have fed me wine until I rolled in the aisle. And they actually have a menu for meals – I chose a lunch of Korean Gogi bokum (fried beef and vegetable) and now I’m torn between the Indian vegetarian delight or the grilled fish and herbs for dinner. Not bad. I need to get some sleep, but there should be plenty of time for that on this 15hour flight. I watched most of Harry Potter and a bit of Ali, but I’m not in the mood for movies. I’ve got all the adventure I can use right here. 3 Saturday, April 6, 9:30 a.m. Ulaanbaatar When in doubt, go off the menu. I settled on seafood spaghetti for dinner, along with a fine red wine. I have to remember that so my memory isn’t stuck on what ate for my next meal and or the experience of the next airline. The remainder of my flight on Singapore Airline was comfortably pleasant. Almost everyone kept the window shades pulled tight the whole flight, although I don’t believe we ever got out of brilliant sunshine. I opened mine periodically to glimpse a changing-but-always-icy landscape. Alaska was spectacular, with huge crags that came right down to the ocean. Anchorage was equally scenic except for the disconcerting pall of brown smog that hovered over it. We followed the arc of the once-joined continents so that we stayed just off the coast of Siberia and down to Japan. I saw little of Siberia except clouds and snow. At the Kamchatka peninsula, the ocean ice broke into thousands of small white pieces that swirled in the current. They looked at first like soap foam. When we landed at Seoul, I was paged by the head cabin attendant, who told me to a gate agent would meet me. And indeed he did. Along with a tall Englishman, I was hurried through the gate by an efficient Korean steward. We were whisked to a special cubicle, where an equally efficient airline official expressed his disgust at how my baggage had been handled and said I would never make it if I had to go find my own bag. He got on the phone, shouted for a minute or two and handed me a receipt. I could pick up my bag at Ulaanbaatar. That left me time to get to know my companion, also on his way to Mongolia. Kenneth Hill is a professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health and is a demographer. He was going to Mongolia as something of a referee to settle an argument between the Mongolians and some world agency over how to calculate the country’s infant mortality rate. He and I had a drink in a small airport café as we waited. I cashed a dollar to pick up some Korean coins (I always try to bring home coins) and listened to his tales of world travel. Although English, he has been an academic in the U.S. for some time and is often off on one of these jaunts. Like me, he had received conflicting messages on what to wear for warmth and (like me) had abandoned his heavy overcoat for layers of lighter jackets. We may both regret that. I’ll see next week. It turns out we are both on the same return flight and will have four or five hours together in Beijing. The flight to Ulaanbaatar was not unpleasant, just a step back 20 years. The level of service and amenities was much like one found in airports in the 1970s and 80s. I boarded early, then watched in fascination as my fellow travelers boarded. It was a veritable fashion show -- a men’s fashion show. Most of those boarding were men in their 30s to 50s, dressed in extremely stylish silk or wool suits. The haircuts were out of GQ and all were carrying computer cases or duty-free bottles of liquor. There were far fewer women, all elegant but not nearly so stylish. As we waited for final departure, the cabin attendant (who was one of the most sophisticated and elegant ladies I have ever seen) passed out newspapers in a half-dozen languages. This gave me a chance to figure out the nationality of the travelers. About a 4 third were Korean, a third were Japanese, less than a third were Mongolian and a scattering (like me) were Yanks. The plane was packed, stuffy and hot. When the meal came, I really missed Singapore Airlines. Not that it was bad – it was just one of those quickly thawed globs of nameless food one always got on United or TWA a few years ago. Four hours later, we touched down in Ulaanbaatar. It was after midnight and all I could see outside was cold landscape made colder by airport-style floodlights. Gate security was a memory from a few years ago also. A few VIPs had people waiting in the gangway tunnel. The rest of us had to get our bags (that Korean guy knew what he was doing) and whisk through customs and immigration (no inspections, just a glance and a stamp) and pass through the portal to the terminal, where the waiting relatives formed a seemingly impenetrable wall. Walking through them was like walking through water – they parted briefly as I approached and then closed back around me as I passed. One oddity at the baggage claim – there were almost as many boxed TV sets, stereos and other electronic appliances on the belt as there were suitcases. I saw a hand in the air and found Oyuna, my host, waiting with a driver. She asked if I knew why the plane was late, but at this hour, I couldn’t remember why I was here. I saw a little of the city as we passed, but it was too dark for detail. Oyuna, an official of the Press Institute, was worried that I would be cold. The week had been quite warm, but a frigid front was moving in and it would be in the 20s or lower. Not to worry, I’ll buy and extra sweater if I need it. My hotel is old, but comfortable. It has the same need of maintenance one finds in older, independent hotels in downtown U.S. No fear of cold here – they control the thermostat and the whole building is at about 75 degrees. I watched TV while I unpacked. Amazing. Cable here carries channels from the U.S., France, Korea, Italy and elsewhere (about 10 countries in all). I watched a National Geographic special until I was too tired not to go to sleep. And now the real adventure begins. I slept in, showered and sat down to write while I could still remember. Oyuna will pick me up at 2 p.m. to review the groundwork they have done on my proposal. I certainly hope I brought the right material. Saturday, April 06, 2002, 10 p.m., Ulaanbaatar: It was a curious day, but as I end it I think I am actually starting to get a grasp of this fascinating country. My hosts had hoped I would sleep until noon, but jet lag doesn’t work that way. I got up about 9 a.m. and wrote in my journal before going downstairs for breakfast. The dining room was very empty – probably because the complimentary breakfast ends at 10 a.m. The waitress insisted I stay, however, and I had a pleasant meal of fried eggs and bacon while I talked to an Australian woman who had come in to buy coffee. There is a rather large group of Australians at the hotel. They are part of the Aussie version of Peace Corps – the Australian Volunteers International (AVI) – and are holding a training sessions for new arrivals. The lady I talked to -- Laura something, I 5 think – is a medical technician who works with blood samples. I first thought she said she was a psychologist, but then she corrected me to a cytologist. She will volunteer here for six months. A colleague also wandered in – a young fellow in an enormous parka who is here to work with the tourism industry. He said he really has no particular background for it but that it sounded interesting. He reminded me of my students in Eugene. After breakfast, I took a short walk. It was not the right weather to promenade as the temperature was near zero and the wind was biting. The area around my hotel is mostly large government buildings and banks, with the odd hotel thrown in. There are very few display-type windows on the fronts of buildings, so it was hard to tell what was what or even what was open. I worked on overheads until my ride showed up at 2 p.m. The Press Institute driver doesn’t speak English and I haven’t mastered a word of Mongolian, but we had a pleasant conversation of nods, nuances and waved hands. His name is Hu-lo, Julio or something close (it turned out to be Hurlee but is pronounces “Whoor-lay”). He struggled equally with my name and settled on Kay-Lied. He is probably in his late 30s or early 40s, animated and a quite talkative. He has a fondness for Mongolian pop music, which is not unlike American folk music with a slightly Asian tone. I like it, especially the singer Saraa, and will try to get a CD or two. Driving through Ulaanbaatar can take one aback. It looks very dirty and barren at first. After a time, however, I realized that the “dirt” was the winter’s accumulation of sand, spread on the roads for traction. It blows into every nook and cranny. I remember the same look in Spokane and other northern cities just before the city crews launched spring cleaning. The starkness is also a product of weather. Buildings are constructed with a minimum of large windows and at this time of year no selfrespecting tree would dare show a leaf. For all that, there is very little litter and only minor amounts of graffiti. And the people are wonderful. They are extremely friendly, polite and energetic. Except for the preponderance of black hair and total absence of black skin, a street scene in Ulaanbaatar is much the same as in Chicago or St. Louis. Most of the city folk are quite stylish and the kids love their Nike sweatshirts and rock band logoware just like American kids do. There are a few exceptions, of course. Baseball hats are everywhere (is that a global condition?), but they are worn with the brim to the front as God and the baseball commissioner ordained it. Sock hats are also popular. Many men of middle age (including Hurlee) sport wool berets that are pulled down on the head so they look more 6 like a brimless baseball cap. On occasion, you also see men in what appears to be traditional coats – long trenchcoats with wide belts on the outside. They don’t appear to be thick, but I don’t see anyone freezing so they must be wool. The older men who wear these coats have the “bandy legged” walk of cowboys and usually have weathered faces. The Press Institute is in an older building that is a bit worse for wear. At least it looks old, although I was told it was built for the PI. I will find out more about the history of the and the building in the week, I’m sure. The interior of the building is very much like a circa 1940s high school building with high ceilings and cracking linoleum. It reminds me of the old Catholic school that was turned into Crow’s Shadow Art Institute on the reservation near Pendleton. An aside – that reference to Crow’s Shadow may be appropriate. The people here are ringers for many of our tribal friends. They have that same soft smile that “Marilyn” from Northern Exposure (a Umatilla/Walla Walla, as I recall) had. Their bearing, mannerisms and even the clip of their speech was all very familiar to me. At one point this afternoon I realized that if the Plateau tribes had been spared the culture-killing effects of meeting whites for a couple hundred more years, the Northwest might have been very much like Mongolia today. Oyuna greeted me with hot tea and conversation. She is a quiet, very businesslike woman in her late 30s or 40s. She apologized for the breakdown in communications, but they realized only this week that many of their messages and all of mine were not getting through to the right e-mail address. I was introduced to several other teachers, all of whom were working Saturday to help the graduating class of the institute’s “diploma” program finish their project newspaper. The institute was set up to provide mid-career training, but has added a six-month diploma program that trains young people to become journalists. It also has a research branch, the project coordinator for which (Poul Erik Nielsen) is a Dane who is arriving this weekend. I hope to meet him Sunday. Eventually I was taken to the classroom and introduce to Baljid, the chief of computing. She is a fireball, a 30-something mother of two whose husband is a physicist at the university. Her English is very good and her accent very American. She is overloaded with energy and curious about everything. She proudly showed me the DSL modem she installed last week and quickly set about configuring my laptop to their network Maybe a bit too quickly. When she restarted the machine, it would not take my password. I tried everything, as did she. I even sent an email to John Meyer and Curt 7 Wohleber, but for good reason got no response -- it was 1 a.m. their time. Eventually, Baljid called a technician from one of the largest ISPs. He came and set down to work on my machine with a vengeance. I was, I admit, sick at the stomach. All my files are on the computer – I did not bring paper. It was going to be a rough week of “winging it” if I could not get the computer to work. But he did, in an interesting way. He restarted it from a disk that had a Windows 98 system on it. Then he looked through the files and changed the name of the user group.. By the time we got done with the computer, it was 7 p.m. I hadn’t noticed it was so late. We worked on the translations of my PowerPoint presentations for another hour and then at 8 p.m., everyone gathered to go home. Hurlee, our driver, used his Hundai sedan to ferry a carload of staff to various Soviet-era (and all that implies) apartment blocks and me to my hotel. I got down to the dining room at 8:45, only to read that it closed at 9 p.m. I could see that my same waitress from breakfast was still working and couldn’t bear to make her stay any longer. Besides, I wasn’t hungry. I had lunch just before my driver took me to the institute. Midday meals are heavy here – “salad” of sliced ox tongue and cucumber, rice, vegetables and three fried cutlets (chicken, beef and pork). I passed on dessert. Instead I bundled up and walked through the night streets of Ulaanbaatar. It was not as cold as this morning and better peopled. There are a lot of very small shops that seem the sell everything from gum to appliances, but I found no major stores open. Lots of friendly folk, though. About half the shops have signs in English and a smattering have German on the signs. I was tempted to go into one of the many Karaoke bars, but decided my singing could set off a diplomatic incident. After 45 minutes, I decided to head home before my smile became permanent from the cold. Tomorrow, two of the institute staff members are taking me to the countryside. First, however, we will go shopping for a pair of long johns. I’m all up for adventure, but not for frostbite. I must, however, tell you why my mood is so good. Just before we left the institute, one of the diploma students walked over and handed me a printout of the front page for the student newspaper. As I looked at it, students and staff slowly gathered around. At first I tried to be very diplomatic. It was a nice looking page that would earn a good grade in my editing class, but it has a few minor flaws. After hemming and hawing a bit, I pointed out a layout error that left the reader clueless as to where a story started. I suggested they move the photo down and the headline to the left, starting the story in column three. 8 This broke the ice like a summer heat wave. Soon we were all pointing at elements of the page and gesturing to each other about the effects of the design. I couldn’t help but smile. Barriers of language and distance were gone. We were no longer Americans and Mongolians, but instead simply people of the page. We are journalists. Sunday, April 7, 2002, 9:30 p.m., Ulaanbaatar: I am not sure Steven Spielberg could top my adventure today. My new colleagues at the Press Institute picked me up for tour of the rural area outside Ulaanbaatar. It was, to say the least, anything but a casual drive in the country. A bitter, bitter cold front has blown into Mongolia. Normally the temperature is rising and spring rains are on their way. The Mongolians without exception dislike the spring here, as it is one continuous series of rainy, cloudy days accented by howling winds. They rather enjoy winter despite the cold, as it is usually accented by the cloudfree and sunny sky that gave the country its nickname, Blue Mongolia. But we struck out all the way around this weekend. We got the cold of winter and its crystalline dry snow. But we also got the dark clouds and the blowing wind. Everyone was worried that I would freeze to death on the trip, though I really think I was layered enough. We first drove to the State Department Store, where I was told to buy a pair of powder blue long johns. Then it was quickly off to the hat department. The clerk kept trying to sell me a huge bear fur cap. I know it was a bargain at $60, but I looked like an extra from Dr. Zhivago. One of the teachers, whose name I couldn’t pronounce and who spoke no English, grabbed a Mongolian version of the Elmer Fudd cap, stuck it on my head and pronounced it good. For $15, I was a warm if funny-looking American. Back to the car, where they piled two of their extra coats on me. I told them I was quite sure I didn’t need them. Quite sure, that is, until we left the city limits. It’s amazing how little paved roadway one really needs. Ask any Mongolian motorist. We crested a hill just outside of Ulaanbaatar and swerved off into a turnout that was home to a huge mound of poles and rocks wrapped in bright blue cloth. The only explanation I could get was “the religious people put it there and by tradition you must drive around it three times.” So the young Press Institute financial officer (Zorig) wheeled his right-hand-drive Volvo in tight concentric circles so we could proceed with good luck. Good thing. Beyond the mound, the “highway” was a narrow smear of asphalt that disappeared every few seconds when the snowy wind turned the world all-white. I was thankful that the dearth of visibility kept our driver’s speed down, as that smear of asphalt did little to hide massive bumps beneath it. Glen Cameron might feel quite at home in Mongolia. Not only is the landscape very similar to eastern Montana, but this here is open range country, partner. Mongolia’s herding economy relies on vast fence-free, publicly owned acreage (hmm, hectarage?). In fact, the country’s lawmakers are only now considering whether they should legalize fenced-in private property. Scattered on hillsides and in valleys were little clusters of 9 gers, the Mongolian native house. We know it by its Turkic name, the yurt. From a distance, a ger looks more like fuel tanks than a house, but it is the home of choice here. Even villages with brick homes have gers in the back yards. We passed a very conventional looking horse race track with a very unconventional clientele. Sunday is race day and for the next several miles we would see colorful herders riding their tough ponies to the track, usually with one blanketed racing steed in tow. I have to make a poor excuse for a reporter’s apology here. I never did find a map of the area, so I had no idea where we were going. The signs were in Cyrillic, so offered no help. And for the life of me, I cannot see how the Mongolians get the spellings they do from the pronunciations they give. What this all means is that we ended up somewhere in some regional center some distance from Ulaanbaatar. I only knew Baljid’s name and only she and driver spoke English. At some point I’ll get a list of names and places to complete this story. [ As it turns out, we were in the Tuv Aimag, near the regional center called Zuunmod 43 kilometers south of Ulaanbaatar. We visited the Manzushir Temple in the Zuunmod Valley at the foot of the Bogd Khan Mountains, 52 kilometers from Ulaanbaatar. The museum brochure lists relicst from the 7th Century BC. ] The aimag was notable for its classic Soviet-era architecture. That means that apartment buildings, stores, government offices and anything other than a ger looked somewhat like a 1920s penitentiary. We picked up another Press Institute fellow there. He is an older man who ran the local paper for years and is now in charge of the PI regional office. He was to be our guide. On his instructions, we plunged off our meager strip of asphalt onto a dirt road cratered with holes and ruts that could swallow a Humvee. Our driver seemed to think it nothing unusual and slalomed around the holes like Parnelli Jones. Eventually we came to a decorated gate that declared we were about to go into a protected area. Our guide told us to wait in the car while he got the key. I looked up and saw this old man in a squash hat running – really running – over the snowy rocks to a set of gers maybe a half mile away. He came back a few minutes later with caretaker who let us in. Our destination was a hidden valley that was the site of a huge monastery [Manzushir] until the 1930s. For hundreds and perhaps thousands of years, Buddhist monks (lamas) came here to erect gers in individual compounds and to pray together at the great temple. They underwent several waves of persecution, but met their match in communist takeover of 1938-40. The monks were driven out and thousands were killed. Then most of the 10 buildings were leveled. In 1990, after the rise of democracy, Mongolia rebuilt one of the temples from photographic records made earlier. Piles of rubble also remain, but no monks. This is now a park. To get to the rebuilt temple, we had to climb a steep and rocky hill in the face of a blizzard. Once when I paused, the left lens popped out of my eyeglasses and into the snow. My blind search in the ice was hopeless. I marked the spot with a large stone and we hurried on to keep up with our group (led by the old man with Olympian stamina). At several points I felt at least marginally in tune with Sir Edmund Hillary. The wind sandblasted my face with ice crystals and the altitude tried to pull my breath from my lungs. I grateful to the Buddha, my Creator and the maker of my borrowed jacket when I finally stumbled up the ornate steps of the temple. The inside was gorgeous. Every piece of wood was hand carved and brightly painted. Displays of native wildlife were mixed with religious alcoves. At one, I was instructed to tap my forehead on the altar to bring prosperity and success to my profession. I tapped. I also added a Yankee Dollar to the pile of token offerings on the altar. The ceremony was repeated at another altar for family happiness (I tapped especially hard for everyone) and we were lead to a final exhibit that I still don’t understand. In a case was the top of a human scull turned into a cup and a woman’s thigh bone turned into a pipe. When I asked how they came about, everyone shrugged. Sometimes I don’t ask for a translation. Back out into the cold to view the outdoor artwork – stone is sacred to Tibetan/Mongolian Buddhists -- and the remains of other temples. Just when my fingers were losing their last bit of feeling, we were ushered into the short door of a ger. Wow. The plain exterior of these huts is very deceptive. Inside they are roomy, bright (from an overhead window at the apex) and warm (from a small but crackling stove in the middle). One of the caretaker families lived in this ger. I got to play with the three children while their mother prepared a traditional treat for us – Mongolian chai. Mongolian chai is not even remotely like the beverage served by the alternative lifestyle folks in Oregon. It was some sort of greasy beef soup (probably tripe) mixed with milk and green tea. Sounds awful but tasted pretty darn good. At the very least, it thawed my innards and gave me a boost. As we enjoyed our chai and the children, the lady of the house returned to her tailoring with a hand-crank sewing machine. When we left, I gave the family a Mizzou pen and a golden dollar coin. The coin was a big hit. I was just amazed by the opportunity to simply drop in on a culture I had only read about in National Geographic. Our host from the ger simply shrugged it off and 11 jogged down the hill to help us find my missing eyeglass lens. We walked and walked around that marker stone. We raked the snow and I even got on my knees to check it from a low angle. Finally I gave up and said we should just get in the car before we all froze to death. As I turned to go, there was the lens in front of me surrounded by the tracks of other searchers. Everyone said it was an auspicious sign. And I believe them. Monday, April 8, 7 a.m., back at the hotel before going off to work: You are owed an explanation of my loquaciousness yesterday. Between the temple and the hotel, we stopped in at an inn for dinner/lunch. It obviously had been arranged in advance, as we were the only customers and the dishes where all set out for us. As we were served the national salad – slices of sausage, cucumbers and cheese – my hosts broke out warm cans of Heineken beer and a 500 ml bottle of Mongolian vodka. A tumbler of the clear liquid was poured for each of us and toasts were given all around. Vodka is consumed here like dinner wine. We had refills as the soup was served and again as the beef goulash and slaw came. The food was good, but we all became louder and louder and more and more talkative. Cecile, I swear I didn’t promise to negotiate world peace or to fix the Mongolian media system. Well, I don’t swear, but I’m pretty sure I didn’t. Besides, I think the hatpicking newspaper design teacher and old guy with Olympian lungs said they could straighten out all those world leaders. And I believe them. Monday, April 8, 2002, 11:20 p.m., Ulaanbaatar: Yesterday I trekked up and down Mongolian hills in the blowing snow. Today I stood in a warm classroom and carefully enunciated a lecture so it could be translated my audience. Last night I was so wired I couldn’t sleep. Tonight I feel on the verge of a coma. Today was the first day of my lecture series at the Press Institute of Mongolia. I have 14 students, ranging from the manager of a commercial web site to a couple of college professors to a page designer of a newspaper that has no web site – yet. Most are quite young, but that is not surprising in a country where more than half the population is younger than 35. The class went well and the students seemed quite responsive to my still. I can see already, however, that I will need to prepare more material for later in the week. Like many young people, they want their information fast and furious. 12 Among the interesting students is a lady who runs the site for the Open Government project. It is a governmental unit dedicated to putting records online. I awoke today with a slight sore throat and a croak in my voice. By noon I was congested and hoarse. Baljid insisted on taking me to a doctor, so at lunch we went to a Korean-run hospital. She talked her way past a couple of nurses so we could see the doctor right away. Nice fellow. He was a Korean ear, nose and throat specialist who spoke English fairly well. He explained that the dry air of Mongolia was hard on American throats, especially after a long airplane ride. He swabbed medicine on my tonsils and gave me a prescription for amoxycillin, ibuprofen and something to clear the congestion. I also need to drink warm liquids often. I croaked through the rest of the lecture, which was odd mostly for its schedule. We start at 9 a.m., take a break at 11 a.m. and continue until lunch at 1 p.m. We return at 2 p.m., but end by 3:30 p.m. Not that my day was over. As soon as class was done, I was asked to gather my coat and hat for a trip to the New Leadership Club. This is an organization for young adults supported by the Social Democratic Party. The SDP was a prime player in the democratic revolution that ended Communist rule, The club funds a Web site that is an experiment in progressive democracy. The site produces no original content, but gathers electronic copies of Mongolian newspapers and puts them online via Adobe Acrobat. They asked me to meet with them to discuss ideas for grant funding to continue the project. The intent is to provide a window on Mongolia both for expatriates and for residents of western nations. I am tentatively scheduled to return Thursday for dinner with the organization’s leaders. At least one of the people I met today was a former cabinet officer. Then back to the Institute for a few hours of prep work for tomorrow’s class. You go through a lot of material in a full day of lecture, so I am worried that I won’t have enough prepared for the end of the week. I finished up and had the PI driver, take me to the hotel at 7. I had another animated hand-gesture conversation with the driver, whose name is actually pronounced Hooly but is spelled Hurlee. I had the PI staff print a list of names for me yesterday. Everyone has an incredibly long formal name (Hurlee’s is D. Hurelbaatar) and what they call a “short name.” Oyunaa, the head of training, is R. Oyuntsetseg. I am thankful for the short name tradition. At the hotel, I called Poul Erik Nielsen. Poul is a Danish professor who oversees the research effort of the institute. He is in town to release their latest report on the status of the media in Mongolia. 13 He and I went to dinner at a little Italian place he knew. We both had quite good pizza, which he said was one of the few spicy dishes served anywhere in Mongolian. Mongolian barbecue, by the way, has nothing to do with Mongolia. Traditional food here is very bland, very boiled and very heavy on meat sauces. I’ve eaten more stew in the past few days than I have eaten for years. Poul and I had a great chat. He works in several developing countries where the Danish government has taken the lead to train journalists. Denmark, he said, frequently has the highest percentage of GNP dedicated to foreign aid. He is a communications professor from “the university” (no one here writes down WHAT university) who has worked in some of the farthest reaches of the world. His project here is an annual inventory of the media in Mongolia. It is really quite impressive. The actual work is done by a Mongolian Ph.D. named M. Munkhmandah, or Mandah. We really need to hook her up with Esther Thorson. Poul agreed with me that Mongolia offers far more than its western reputation. It is a country of strong journalistic ideals. People here seem to be driven to write and have little concern for the economics of the journalism industry. The Danes are most proud of the Printing Center that they built in conjunction with the Press Institute. It offers low-cost offset printing and is responsible for the explosion of newspaper titles in Mongolia. The center now prints about 60 percent of the newspaper titles in the country (mostly weeklies). I will try to go visit the press crew with Poul. The operation is very efficient and has somehow learned to run good color with small press runs. I want to take some pictures for an article that I could do later via e-mail interviews. After class today I am scheduled to go to a concert of Tumen eh, the national folk group. I will also go shopping with Bagi, the Press Institute secretary, who apparently knows the best places for bargains. But for now, sleep. I’m beat. Tuesday, April 9, 2002, 9:50 p.m., Ulaanbaatar: I just had a great cross-cultural experience. I had flipped on the television set flopped down on the small couch in my room with my laptop to edit today’s photos. I was just interested in background noise, so clicked the channels until I heard music. It was a Korean station’s MTV-type program. About 10 minutes later, I found myself tapping my toes to the beat of a rapper and realized I was listening to an Asian version of “Living in a Ganster’s Paradise.” I paid attention long enough to spot a Korean Brittany Spears and a boy group that was cut from the Ensync mold. When the music show ended, I flipped the channel switch again and found the Russian version of “Weakest Link.” Exact same set, exact same sound effects, and exact same glasses on the stern-looking female host. Tomorrow I will ask if someone will videotape television commercials for me. It is just fascinating to watch the variations on them when you can switch between channels from Mongolia, China, Singapore, Italy, Korea, Russia, Spain, Australia and Great 14 Britain. I found it interesting that the greatest concentration of commercials is on one of the Russian channels. Many of the Russian ads also have the best production values. Ah, but all the television in the world could not top my real cultural experience today. After work I accompanied the Institute’s secretary, Bagi, and my friend Hurlee, the driver, to a National Folk Ensemble concert. Unfortunately, I did not think photographs would be allowed so I left the digital camera behind. When everyone started flashing, however, I pulled the little 35 mm from my pocket and finished up the end of a roll. It was nothing short of spectacular. The group performs in a theater of traditional style. This means that the “stage” is a large sunken square flanked by doors. The audience enters one of the doors and walks across the stage to a set of carpeted risers that wrap around three sides of the square. When the performance begins, the players enter and exit by the same set of door. The advantage is that the audience is very close to the action – no player was more than 20 feet from me. Mongolian traditional instruments are sort of a cross between Chinese traditional instruments and European instruments. Long, skinny stringed instruments are paired with flutes, stringed base and hammer dulcimer. One woman played a uniquely shaped harp with such proficiency that I was agog. One hand plucked a lilting base line while the other picked and staccato melody that would put Flat and Scruggs to shame. To demonstrate the range of the instruments, the group played one classical European piece that I think is called Rondo, but my music memory has never been good. It was wonderful. Next a dance troupe performed a wonderful piece in which the women put porcelain bowls on their head and chimed a beat with another set of bowls in each hand. At the conclusion of the dance, the women stacked the “hand” bowls into the bowl on their head and continued to dance. Each dancer would perform a shudder that would make the stack of bowls clink rhythmically like a belly dancer’s bells. I have to say that my favorite act was a long-faced fellow who played a Mongolian version of the cello while “throat singing.” This is a bizarre trick in which the singer appears to “swallow” a low note while searching for the same tone on the stringed instrument. When they match, it sets of a harmonic that is other-worldly. It sounds something like computer-generated feedback. Even that was pretty tame compared to the contortionist. A woman in tights came out and proceeded to twist her body into shapes no body was designed for. At one point she was lying on her stomach with her knees bent. She pulled her head back and placed the back of her head squarely on her bottom. The finally was a traditional religious dance that brought out the whole company. Musicians played large gongs and a giant trumpet (at least 10-feet long). Meanwhile, the dancers entered wearing huge painted masks that represented gods. It was colorful beyond belief. In the more mundane world, my froggy throat has begun to clear and I had a good class. We have finished most of the background material and now the students are seeing how this can help their particular site. I also had a talk with the PI people about my 15 invitation to dinner with the politicians. They would rather I not appear to “pick sides” so they will make an excuse for me. Meanwhile, I have a command performance on tap with the Soros Foundation leaders tomorrow. I will continue to try to get a few street scene photos if I can do it without being obnoxious. I love the contradiction of people in traditional long coats and fur hats with businessmen in Italian suits and young women in Vogue couture. I was sorely tempted by one opportunity to experience Mongolia today. Hurlee had to take me back to my hotel to pick up a paper I had left behind. As we got to the edge of the parking lot, he pounded his steering wheel, sapped my leg and then raised his eyebrows as if asking a question. He wanted to know if I would like to drive back to the hotel myself. It is hard to explain the driving technique of Mongolians. Signs and stoplights have only marginal authority. I’m not sure why anyone wastes paint on crosswalks, as pedestrians have no right to safety at all. And road maintenance is something that only accompanies the return of Halley’s Comet. Hurlee is a character and I like him very much. And driving a breakneck speed while dodging Russian-made jeeps and car-eating potholes actually sounds like fun. But I really should try to survive the week. “Thanks, but no thanks.” Wednesday, April 10, 2002, 10:05 p.m., Ulaanbaatar: I had an unusual “déjà vu” meal this evening. As part of my “official” schedule, I was asked to dine with official for the Soros Foundation. The two women who are the mainstays of the foundation’s Mongolian operation, Norov and Aruinaa, are bright, interesting and very dedicated to their jobs. Halfway through the dinner, I suddenly thought I was having dinner with Pat Walters and Rafael Hoffman, our friends from Pendleton. The physical resemblance was close, but the personality resemblance was remarkable. As I have said before, Mongolians are close relatives to Native Americans. A Turkish journalist I met today who has lived here for nearly a decade told me that medical tests have shown the two peoples to be genetically identical. Norov (people here only use one name) was my Pat Walters. She is quiet, serious and always looks a bit tired. But she can flash a smile the lights the room. She directs the media programs for the foundation, which is an international group endowed by American billionaire George Soros and dedicated to helping emerging democracies during the transition from Communism or authoritarianism. Aruinaa, though, is a kindred soul from Rafael. She is loud, flamboyant and energetic. She wears here hair long and coifed like that of a movie star – somewhat unusual for mature women here. Both women were elegantly dressed in name-brand western clothes, but Aruinaa accented her outfit with a scarf tied around her throat. Like I said, she is Rafael in another land. The dinner was a fitting end to fine day. We ate at an Indian restaurant where I 16 gorged myself on dishes I could not pronounce. After several days of the boiled beef and the spiceless stew served at all Mongolian meals, the fiery spices of the Indian food was a pleasant break. My hosts wanted to hear my observations on Mongolian life and the Mongolian people. The said they were embarrassed when I raved about the friendliness and critical thinking skills of their countrymen. I may have taken it too far – they tried hard to talk me into returning to Ulaanbaatar next month to teach community newspaper management. The foundation has a number of interesting projects that use journalism to build a sense of community. Norov is in charge of one project that has developed seven rural radio stations. They are also helping the editors and publishers of small rural newspapers develop their skills. I think the University of Missouri could develop an interesting relationship with Mongolia. The country is a goldmine of scholastic opportunity. For instance, there is a terrific need for media use and audience analysis research so they can build a free market mass media system from the ashes of Communism. It is the type of project that a student research team could accomplish in a summer. The English language skills here are generally good, so there it would be very possible to connect Mongolian journalism students with students in our classes via the Internet. My hosts also requested that I provide them information on the Center for the Digital Globe, which interests them as a concept. I actually woke up today on the wrong side of the bed. More accurately, I woke up with the covers wadded in a not around my head. I had a hard time waking and was probably less than sociable when Cecile called. But I came around after a couple cups of coffee while reviewing my course notes. We finished up on the writing lesson this morning and then started audience analysis. I had the students divide into three teams and had each of the list as many audience segments as they could. It was a good exercise that took quite a long time, as each group slowly explained their view of the Mongolian audience while the translator kept me abreast. At lunch I sat with Poul Nielsen and his Turkish associate, Mustaffa.. Mustaffa runs a web site and teaches English and Turkish at the Mongolian military academy. He came here as a working journalists, married a Mongolian woman and settled down. He is divorced now, but doesn’t want to leave his children. Mustaffa said he has seen a dramatic change in the Mongolian people since the advent of free enterprise – and it was not a pleasant change. He said that under the socialist system, Mongolians were well known for the collegiality and selfless enthusiasm. Now, he said, everyone is working on a scheme to get rich., Poul, Mustaffa and I are having dinner tomorrow. It should be fun. Another great part of my day was taking a class picture. Everyone was enthusiastic about it, which told me they have real interest in the class. When class ended at 3:30 p.m., Baljid and I went to the Mongol News building to tour its newspapers. They have one of the largest (10,000) dailies here, plus the UB Post, 17 an English language weekly. The UB Post editor in particular is interested in both training opportunity for her current staff and posting job opportunities to our students. Working here would not be a bad gig. The money is minimal, but so is the cost of living. The American fellow who serves as copy desk chief told me that income is a relative term here, as many expenses are handled as “favors” to employees and associates. I had a great time in their pressroom. They have a 1970s-era Japanese press that looks like it would rattle itself into a million pieces if it ran at full speed. But they print several editions on it and even do a bit of color work. It has only six units, so they can’t get much volume out of it. The press crew chief said they pay about 70 cents per kilo for newsprint. It all comes from China. They burn their plates on positive material, using a sort of “onionskin” paper in the laser printer to produce page galleys. It eliminates the need for negatives. Thursday I will have the students spend the day working on the three strategies I offered for online media in Mongolia: Online for the domestic market, online for expatriate Mongolians and online for tourists. But now I need to get some sleep so I don’t wake up a grouch again. Thursday, April 11, 2002, 11:25 p.m., Ulaanbaatar: The clock is ticking as I begin to wind down my Mongolian adventure. Today was one of those times where everyone wanted a piece of me for at least a few minutes. I expect that Friday, my last day at the Press Institute, will be even more intense. Of course, the morning couldn’t get any weirder. I knew that Cecile would call me at about 7:30 a.m., so I sat patiently by the phone waiting. I need to be ready to catch my ride shortly after 8 a.m., but the restaurant doesn’t open for breakfast until 7:30 a.m. After listening to my stomach growl for several minutes, I finally went down to the reception desk to find out what was up. The phone was ringing, but I could see no clerk. When I peeked behind the desk, there he was sound asleep on the floor. No amount of calling would wake him, so I had to shake his foot to rouse him. I told him to answer the phone and transfer the call to me. I jogged back to my room, but received no call. Again a trip to the reception area and again no clerk. This time he was on his back sound asleep again – but holding the phone in his hand. It took some work and a bit of angry shouting, but eventually I got my call. My class was very good today. Now that they have a good background on online theory, I divided them into two teams and gave them three scenarios to use to propose online publications. One was for an in-Mongolia site, the other was for expatriate Mongolians and the third was to attract tourists. We spent the day in lively discussion and intense brainstorming. They did very well and handled some complex problems. I was very proud of them. Friday each student will review another student’s website. I’ll chime in with my own opinions. It should be fun. 18 We had a farewell dinner scheduled, but that has been changed to a farewell luncheon for me and Poul Erik Neilsen, the Danish professor who is here. Then after class I am to be interviewed for a journalism magazine and then I give a guest lecture on media management to an invited group of editors, publishers and officials. But wait, there is more. We will adjourn for a “meeting” of PI staff that promises to continue into the late hours of the night. The staff at the Press Institute of Mongolia has an interesting tradition of final “meetings.” When a visitor is about to leave, everyone is invited to a “meeting over the flowers,” it means someone will bring some flowers and someone else will bring the vodka. The meeting becomes an all-night party. After class, I was given a tour of the Free Press printing facility. This is a remarkable facility initially funded by Denmark. The Danes accurately figured that if they provided the technical infrastructure for a newspaper industry, free press would follow. Now the facility prints some 300 publications, including two daily papers. It is a non-profit, but publishers pay the accurate cost of printing. The press room was spectacular. Clean as a whistle and very modern. They import quality newsprint from Finland for $600 per metric ton. I had a great time swapping printing stories with the director. On the way back upstairs to the Press Institute, I reacquainted myself with one of the differences between the U.S. and Mongolia. Here stair steps have no standard height and vary by as much as two inches in a single flight of stairs. That’s not good for those of us with bifocals and even worse if you are in the habit of not watching where you are going. If I don’t show up on time Saturday, look for me sprawled on a set of steps in Ulaanbaatar. After the tour I went shopping with Bagi, the secretary, and Hurlee, the driver. We were supposed to just run out the cashmere factory outlet and dash back to the institute so I could help judge a website contest, but the two of them decided I had not seen enough of Ulaanbaatar. At the cashmere factory, they dressed me up in a yak herders long coat and took my picture. Then they drove me through some colorful areas, pointing out temples and museums. Hurlee said we needed beer, so he stopped in a somewhat seedy shopping area. While he was in the store, several men wandered up to offer various trinkets for sale. I bought a few old coins, but passed on the brass camel. Then a fellow strolled up and asked me if I would like a pair of Russian officer’s binoculars. I couldn’t resist trying them, as Russian optics have a great reputation. He said they were normally the equivalent of $250, but for me he would part with them for 19 $60. I looked at them, drooled, but said I wouldn’t think of paying more than $30. To my surprise, I now own a very fine pair of binoculars that sport the hammer and sickle emblem. Armed with a couple of large cans of warm beer and my new toys, we drove “to the mountain.” On a large hill overlooking Ulaanbaatar, the s built a huge monument to Soviet/Mongolian cooperation in World War II. Apparently Mongolian troops had a greeat tank brigade that played a crucial role in the Red Army march to Berlin. It makes some sense – Mongolians on horses earlier led a charge across Asia and into Europe. You have to hand it to the Russians. For all their dullness in apartment design, they have a special knack for monumental architecture. I didn’t have the digital camera with me, but I took lots of pictures with the 35 mm. The view was impressive, even though the cold drought of winter has left the surrounding countryside the color of a grocery bag. I’ve seen photos of the summer, when Mongolia is green rolling hills for as far as one can see. Off to one side of the monument was a traditional Mongolian Buddhist shrine. It was simply a pile of rocks draped with blue cloth. I joined Bagi and Hurlee in the requisite three circles around the pile and learned that I could show good form by periodically picking up a small stone from the edge of the pile and tossing it to the top. Later Hurlee showed me his “hanging god,” which is an icon in a small leather bag that hangs from his rear view mirror. He touches his head to it for luck and safety, and when the traffic is really bad, he takes it down and hangs it around his neck. From the top of the hill, one could see how Ulaanbaatar is spreading. At the edges of the city are neighborhoods of gers, the Mongolian tent building. People are not supposed to move here from the countryside without a permit, but the tide is relentless anyway. Newcomers usually pitch their ger in one of these fringe neighborhoods. After we drove down the hill, we visited a large temple. They wanted to show me the large Buddha, but that part of the temple complex was closed for the evening. So they told me I should get one last pass at the state department store. What a gas. I found some great souvenirs for folks. Back to the institute, where I spent another hour judging web sites. By now it was 8:30 a.m. and I was starving. When I finally got to the hotel, a note awaited me from Poul saying he and Mustaffa had gone to an Indian restaurant nearby and I should join them. Something did not quite connect when a Dane left a note for an American about 20 how to find a Turk in Mongolia. I walked up and down the street but could not find the restaurant. I finally did find Poul and Mustaffa, however – walking back to the hotel after dinner. Mustaffa had to leave, but Poul said he would join me for a beer while I ate. I wasn’t in the mood for Indian, so we went to “Le Rendezvous,” which features Khan Brau beer on tap. Sounds odd, but that was the best beer I have ever tasted. Poul said some German brewers settled here and set the standard for fine suds. It went well with my mutton sauté – a very tasty mixture of meat, green peppers, onions and something I didn’t really want to ask about. I had a wonderful conversation with Poul. Like me, he is enchanted and befuddled by this country. It’s Russia, it’s China, it’s France and it’s the United States. And yet it is also an ancient culture of its own. We agreed that neither of us would probably ever get the “whole story” of Mongolian life, but it was fun searching. By the way, Poul used his trip here to propose a major research project. He wants to organize an independent group to provide unbiased statistics on media audiences. Right now, the reader and viewer stats are mostly wishful thinking and braggadocio. This could be another opportunity for Missouri to help. Saturday, April 13, 2002, 7:15 a.m. CDT., Over the Sea of Okhosk near Siberia; Homeward bound, with a head full of memories and heart full of longing. It has been a week of adventure, friendship and learning. It ended with a whirlwind of meetings, greetings and partings. I’m very glad to be on my way back to the arms of my family, but I will miss a country and a people that only a week ago were just characters in a travelogue. It was all I could do to pull myself from bed Friday morning. My body was finally adjusting to the Mongolian time zone, which meant I really did want to sleep in when the alarm range at 6:30 a.m. But this was the last day of the seminar and I had more than a little work to do to prepare for my students. Today we would critique Mongolian web sites, summarize the class and then I would give a special lecture to the Mongolian press corps about media management. The day dawned a bit cloudier than before, but still fairly warm. A warm April morning in Ulaanbaatar is when your breath does not freeze, but it was still pleasant enough that I could go to the Press Institute without my parka. Previously I had assigned a web site to each student. We had agreed to give them the first hour of the day to look at the sites and prepare their notes, so I had a bit of time to work on overheads for the management lecture. When I first “volunteered” for the lecture, I was told that a few editors would attend. Friday morning I learned that the PI director had personally called the CEOs of all the leading media outlets to invite them and their key managers. My mood needed no Mongolian translation – I was plain nervous. The students did a great job with their critiques. Each called up a site on the projector and told us about its attributes and how they would improve it. No one was 21 allowed to review their own site, but I made sure that everyone who wanted their site critiqued was covered. When the week began, some of the students were a bit irritated that I had come all the way from America but did not plan to talk about technology and computer programs. But today, my lectures on theory and content paid off. They all found ways to better address the audience and were quick to volunteer content improvements even to their own competitors. Lunch was a very special time. Tseden-Ish (“Mr. Ish”) , the PI director, wanted to take me to lunch himself. Our interpreter, Tulgaa, and Baljid accompanied me as we set off for a culinary extravaganza. I, of course, had no idea where we were going as Mr. Ish whizzed through the streets of Ulaanbaatar in his Kia Sportage. The destination, I found, was the immense Hotel Ulaanbaatar. The elevators were being repaired, so we had to walk up four flights of stairs as I became increasingly puzzled (not to mention winded). At the top, I was led to a large room that to my surprise contained an entire ger. And not just some goat herder’s ger, but a ceremonial structure of fine wood, fur and canvas. It was bizarre but exciting to find oneself in an elegant European-style restaurant that was empty except for this very large tent. The crisp and efficient hostess guided me to the low doorway and I was take to the seat of honor – farthest away from the drafts of the door. The ger was very large and very opulent. As always, a warm wood stove defined the center, it’s pipe snaking up the skylight-adorned center hole. Around the edge were traditional carved beds and couches. Our table was hand-carved with Mongolian figures, and set with a staggering array of delicacies. Peking duck, lightly-fried fish, steamed vegetables, rice and meats. This was something right out of “The Food Channel.” I ate to bursting and then blushed as Mr. Ish gave a speech about how I had brought both friendship and knowledge to the Press Institute. Needless to say, we returned from lunch a bit later than usual. Not to worry, as the students seemed to know it was a special day and were eager just to talk with each other as they waited for class to resume. After our final critique, we had a brief closing ceremony. I gave each student at golden dollar coin, noting that it carried both the lucky soaring eagle of the United States and the image of Sacagawea. Lewis and Clark used all the technology that the early 19th Century white world could offer to prepare for their trek across the continent. But they were guided by a pregnant teenage girl in hand-worked leather – a young woman who gracefully shared the same hardships as the experienced soldiers in the Company of Discovery while giving birth and caring to an infant. The Mongolians are genetically linked to the American Indian and rather proud of it. I told them they should also be proud that they are showing the online world that they can successfully compete without the modern infrastructure of the United States. 22 After my students said their farewells, I quickly readied for the management lecture. What I found was a large hall packed with sober-looking media executives surrounded by their younger staff members. It had all the trappings of a speech at the Press Club. I thanked my lucky stars that the day before I had asked one of my hosts why Chinggis Khan was so revered in Mongolia. I was told that the people loved him because he invented a layered governmental system in which each official was both responsible for and took advice from a group of people below him. No great decision was made, they said, until it was discussed by the lay people and their comments were passed upward. The editors loved my allusion to their national history, even though I saw a couple of older executives wince when I said no modern manager could act like a dictator. Pens scribbled furiously as I gave them an outline on basic management structure and responsibilities. (I later heard that the three top lieutenants to the publisher of the largest daily planned to go back with their notes and demand he change his ways. Good thing this was my last day.) I answered questions for a considerable time until the dean of the Mongolian press corps signaled an end. Like Helen Thomas, he got the last word. He summarized what I had said, thanked me eloquently and then invited me to return to Mongolia to see how my words had taken root. I was almost speechless. And I prayed to God that I gave them the right advice. It is one thing to muff a class lecture. It would be quite another to screw up a nation’s press system. I have and collected many cards and handshakes. When only the Press Institute folk were left, it was time for a “meeting with flowers.” Mongolians think flowes are the key to a woman’s heart and to a lifted spirit. So they use the term to describe a party of farewell or welcome. Ours was both. Poul Neilsen from Denmark and I were leaving in the morning, and Oyungerel had returned from Missouri. So the tiny glasses were arranged on tray and filled with vodka. One of the staff members circulated with the tray like a deacon offering communion cups. Glasses were lifted and the toast began. It was one heck of party. We ate from trays of sausage and fruit and the tiny glasses were constantly replenished. When I asked for something more quenching to go with my food, I was given first a large glass of wine and then a glass of Kirsch. The Mongolians are a very musical people, so one by one members of the PI staff rose to sing traditional songs. Batjargal, who is half Mongolian Eskimo, delighted us a song in the language of that ethnic group. Hurlee, the driver, 23 sang the national “long song,” and almost brought tears to people’s eyes. And then everyone asked Gunjee, a research, to sing “her” song. She rose and started an enchanting melody. I noticed that everyone’s lips were moving and within a few moments even the most formal of staff members were singing along loudly. This was the Mongolian song of motherhood, family and love of country. I would have given my salary at the moment to know enough Mongolian to sing along. It was one of the most moving moments in my entire life. More songs, more vodka and then a bottle of Scotch. I think I remember the night winding down, but I can’t say for sure. I know that when I got back to the hotel to pack I opened the window to let the cold air blast my face so I could cope with the latches of the suitcase. That open window later let me know how the young of Ulaanbaatar spend Friday nights. I dozed off to the sound of people laughing and cavorting in the street in front of the hotel. At 3 a.m. I was awaked by a particularly loud peal of laughter. I went to the window to see if folks were really still out there – and was surprised to see that it was snowing heavily. That didn’t dampen the party spirit and they were still at it when I staggered back to bed. I rose early , finished my packing and walked downstairs for breakfast. My regular waitress had her toddler daughter with her, and this young tyke seemed enthralled with me. I gave here a coin and later gave her a Mizzou pencil. I think I made a new friend. I had 45 minutes until the driver would arrive, so I went for a last walk through downtown Ulaanbaatar. I wanted to buy a few more trinkets, so strode off toward the State Department Store about a mile away. It was gorgeous. The sun was brilliant against the new snow. Everywhere workers with long-bristled brooms like those of witches in fairy tales were sweeping the dry snow from sidewalks and streets. Teams of workers were even scooping snow and traction sand into bags and hauling it away. I walked through Lenin Park and past the banks and offices to the department store. Mongolians don’t like mornings, so I wasn’t surprised that it did not open until about 10 a.m. The walk was wonderful anyway. Hurlee arrived, we loaded the car and drove to the airport. Baljid was there to see me of and Mandah, the chief researcher, was there to say farewell to Poul. Both were visibly shaken. I gave Baljid the online journalism book I had reviewed on the plan (and loved) and promised to keep in touch by e-mail. Hugs, teary eyes and goodbyes. Poul took me off to International Departures and introduced me to a very fine duty free shop. Despite a slight headache, I bought my own bottle of Chinggas Khan vodka along with some toys and a pair of ceremonial hats. The ride to Beijing was unnoteworthy, other than it gave me a chance to see Ken Hill from Johns Hopkins. In Beijing, he let me put one of my bags on his cart as we went through the first of many official inspection stations. The clerk took my passport, looked puzzled, then called a uniformed officer. The 24 young gentlemen spoke good English and asked me to go with him. Apparently, whoever told us we needed no transit visa in China was very wrong. A procession of uniformed officers came to talk to me. One said that if I had a friend in Beijing, the friend could invite me to the country and they would issue a new visa. He said calling the embassy was of no use, as it was some sort of holiday. Finally the said that I could pay a $250 fine and be on my way. They took me to a machine, but I found it required one to insert U.S. dollars to get yuan in return. Not that I had $250 in cash on me. Next stop, a bank. By now my original officers was quite embarrassed and very friendly. He said this same thing happened to a University of Missouri professor last year. We must be getting our bad advice from the same source. We discussed his TOEFL test and his desire to study English and law in the U.S. I gave him my card and assured him I wasn’t angry. It took two hours, including the half hour in the United Airline line. The airline computers were down, so everything had to be checked by hand. The Chinese also have no shortage of bureaucratic steps. I had to show my passport and ticket to at least four officials in different uniforms behind different desks. By the time I hit the departure area, all I could think of was a cold beer and a comfortable chair. I had steamed buns in the restaurant, refreshed myself with the beer and went to look for Ken. I met a couple of American businessmen instead who were incredulous about my tales of Mongolia. Like many of us, they thought Mongolia was just a primitive wasteland. Ken showed up as we board and I retrieved my bag. Now I sit next to a sleeping electronic engineer from Philadelphia who was born in China. I couldn’t sleep. My head is still rushing with images of a wonderful land and wonderful people. If this is adventure, give me more. 25 26