A Scaffold for Effective Essay Writing

advertisement

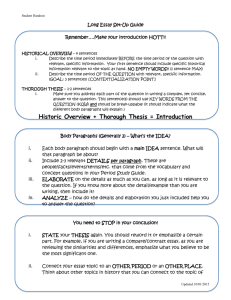

A Scaffold for Effective Essay Writing Introductory paragraph: Begin with a general hook or insightful point (something to get the reader’s attention). Explain your “hook.” Provide another, more specific, hook or insightful point. Explain this hook. Provide a “blueprint” for your essay: Briefly identify what you will discuss in your body paragraphs. End with a thesis statement—a single sentence that explains the entire point of your essay. Body paragraphs: (Q: How many body paragraphs? A: As many as there need to be …) Begin body paragraphs with a topic sentence. This sentence represents one point or major argument that is directly related to your thesis statement. Supporting details: the rest of the sentences in the paragraph should relate to the topic sentence. They may include quotations, evidence, explanations, or points that back up the topic sentence. Concluding paragraph: Do NOT just restate your thesis statement (I’m sorry if you were taught that!). Do NOT begin with “In conclusion…” It is unprofessional. Q: So what do you do? A: Keep reading … Take the ideas from your introduction and topic sentences and synthesize them: o Make an insightful point based on everything you have written so far. o Draw a connection between your essay and something relevant to the real world: something from class, something from literature, something from history, something from current issues, and so on… o Your writing should answer the question “So what?” In other words, think about the whole point in writing this essay. Why are you writing it? What were you trying to accomplish? Why would / should anyone be interested in reading it? Effective writers … use the following in their writing … avoid the following in their writing … Appropriate perspective (1st and 2nd for letters, 3rd for essays). Present tense to discuss the plot of a story. Transitions at the beginning of body and concluding paragraphs. Few pronouns (they use creative and effective antecedents instead!). Proper punctuation and capitalization, including the correct way to punctuate the titles of … Poems—“The Road Not Taken” Short Stories—“The Jewels” Novels—The Three Musketeers Other works of literature—the general rule is to use quotations for “short” works, and italics for “longer” works. They assume that their audience is somewhat familiar with their topic. In other words, they do not explain simple details about the topic or story, but they do explain subtle or complex points about the topic or story. Effective writers PROOFREAD their work. Effective writers will REVISE and EDIT their work and NEVER assume that a first draft is “good enough” to turn in. Inappropriate perspective (1st person in an essay, for example). Past tense when discussing the plot of a story. Contractions. They are unprofessional. Weak words. Examples include things, good, bad, great, very, many, some, this, that. (This or that are weak when they are alone). A lot. This word can only refer to a place to park a car or build a house. Shorthand. Examples include b/c for “because,” @ for “at,” or abbreviating a word because the writer is too lazy to write out the complete word. Spelling errors. Take advantage of the computer’s spell checker. Clichés or slang. Examples include “cool,” “trippin,” “in conclusion,” or “in society today.” Simple mistakes with homophones (words that sound alike). Examples include: your vs. you’re its vs. it’s there vs. they’re vs. their (hint: avoiding contractions will, for the most part, make this problem a non-issue.)