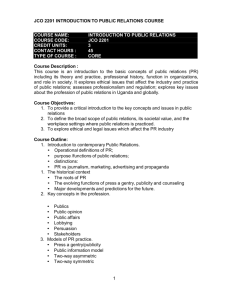

Academic professionalism in the UK context: a

advertisement