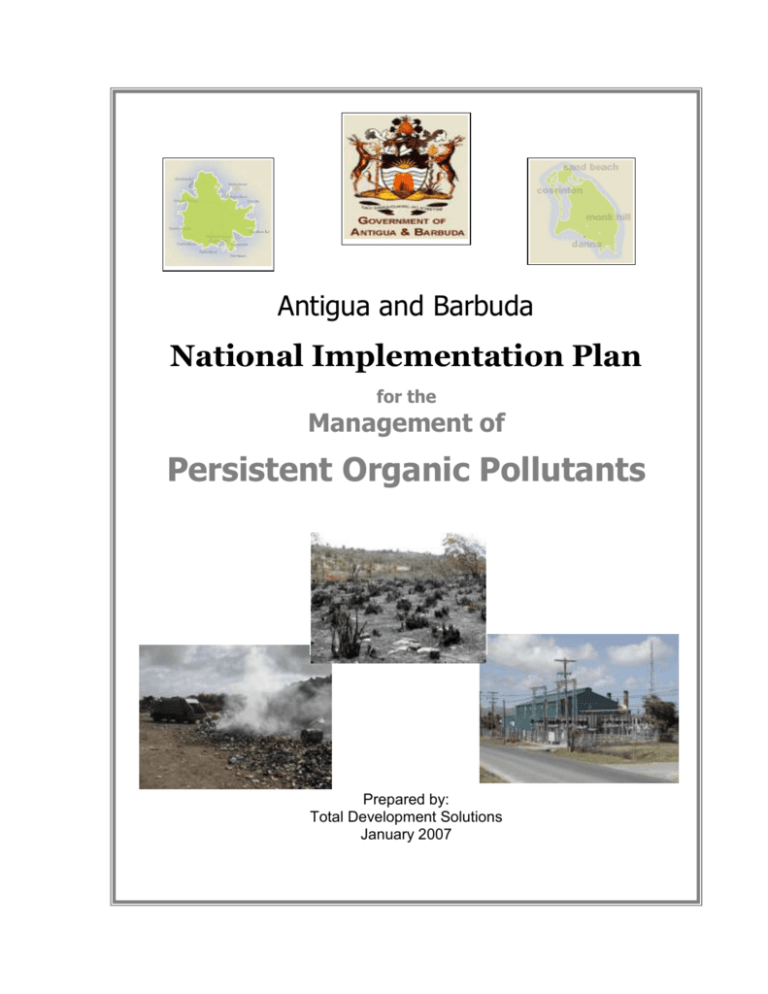

Heavy fuel powered engines (APUA)

advertisement