Microsoft Word - WP-FRONTPAGE

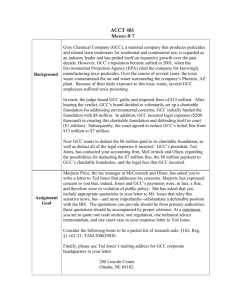

advertisement